Sinkhole Clusters After Heavy Rainstorms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sottoprefettura Di San Severo Atti Di Leva

ARCHIVIO DI STATO DI FOGGIA, inventario del fondo SOTTOPREFETTURA DI SAN SEVERO, ATTI DI LEVA SOTTOPREFETTURA D I SAN SEVERO ATTI DI LEVA (CLASSI 1854 - 1896) ANNO PACCO COMUNE OSSERVAZIONI 1854 1 Apricena Cagnano Varano Castelnuovo della Daunia Celenza Valfortore San Giovanni Rotondo S. Marco in Lamis Sannicandro Garganico San Severo Serracapriola Rodi Garganico Torremaggiore Vico Garganico 1855 2 Apricena Cagnano Varano Castelnuovo della Daunia Celenza Valfortore Pagina 1 ARCHIVIO DI STATO DI FOGGIA, inventario del fondo SOTTOPREFETTURA DI SAN SEVERO, ATTI DI LEVA ANNO PACCO COMUNE OSSERVAZIONI 1855 2 San Giovanni Rotondo S. Marco in Lamis Sannicandro Garganico San Severo Serracapriola Rodi Garganico Torremaggiore Vico Garganico 1856 3 Apricena Cagnano Varano Castelnuovo della Daunia Celenza Valfortore Rodi Garganico San Giovanni Rotondo Serracapriola Sannicandro Garganico San Marco in Lamis San Severo Torremaggiore Vico Garganico 1857 4 Apricena Cagnano Varano Castelnuovo della Daunia Celenza Valfortore Rodi Garganico San Giovanni Rotondo Pagina 2 ARCHIVIO DI STATO DI FOGGIA, inventario del fondo SOTTOPREFETTURA DI SAN SEVERO, ATTI DI LEVA ANNO PACCO COMUNE OSSERVAZIONI 1857 4 San Marco in Lamis Sannicandro Garganico San Severo Serracapriola Torremaggiore Vico Garganico 1858 5 Apricena Cagnano Varano Castelnuovo della Daunia Celenza Valfortore Rodi Garganico San Giovanni Rotondo San Marco in Lamis San Severo Sannicandro Garganico Serracapriola Torremaggiore 1859 6 Apricena Cagnano Varano Castelnuovo della Daunia Celenza Valfortore -

Chapter 9 the Gargano

CHAPTER 9 THE GARGANO The Gargano has the aspect of a region with its own physical characteristics. This physical character mirrors also in the dialects, that show some common feature that distinguishes them from the other middle-south parlances. Gargano’s history dates back to the Byzantine dominations. In terms of language, the Gargano area is anything but uniform. The southern part with the cities of Manfredonia, Monte Sant’Angelo and Vieste underlines some characteristics of the Foggia dialect. The northern part from Lesina up to Peschici, with the most southern points in San Marco in Lamis, Rignano and San Giovanni Rotondo, are more inclined toward the “Subappenino dauno”. Opened to South, the Gargano keeps some phonetic characteristics recognizable in the shaken and mixed vocalic sounds. The strongest point is Peschici which is a hinge between the promontory’s southern and northern part. Rohlfs7 supposes the existence of ancient Slavic colonies on the Gargano coasts because of the survival of a certain number of hypothetical Slavic words and takes account of the failed adaptation of LL in dd in Peschici that with other towns in the “Subappennino dauno” outline a conformity of the same conditions. For the vocalism, it’s important to take account of the failed palatalization of the tonic a in all the positions in Peschici, Vico, Cagnano, San Marco in Lamis, Poggio Imperiale and Lesina, against the palatal d in all the other province’s parlances. In a diachronic evaluation, we must outline that the Gargano, in its geographical eccentricity represents an area less exposed than the rest of the region and so more conservative. -

Autolinea SAN MARCO in LAMIS-S.GIOVANNI R.-MANFREDONIA Sede Regionale Della Puglia ORBA738-20A.Xlsx Orario in Vigore Dal 1° Luglio 2020

Autolinea SAN MARCO IN LAMIS-S.GIOVANNI R.-MANFREDONIA Sede Regionale della Puglia ORBA738-20A.xlsx Orario in vigore dal 1° luglio 2020 Cadenza fer fer fer fer FEST fer fer fer fer scol FEST fer ns scol GIOR fer fer fer fer fer GIOR (6-7-9- (11-20- Note (1) (2-22) (3) (4) (5-21) (2) (6) (20) (3-20) (6-7-21) (6-7-8-22) 22) (6-7-9) (2-21) (6-22) (2) (10) (11) 24) S. MARCO IN LAMIS 05:50 06:30 07:15 08:30 10:00 10:30 11:30 - 12:50 - 13:25 13:50 13:55 - - 15:35 - 17:15 18:35 - 21:30 Borgo Celano 06:00 06:40 07:25 08:40 10:10 10:40 11:40 - 13:00 - 13:30 14:00 14:05 - - 15:45 - 17:25 18:45 - 21:40 S. GIOVANNI ROTONDO | | | 08:45 10:15 | 11:45 - 13:05 - 13:40 | | - - 15:55 - | | - | Conv. Capp. 06:05 06:45 07:30 08:50 10:20 10:45 11:50 12:00 13:15 13:15 13:45 14:05 14:10 14:10 14:10 16:00 15:50 17:30 18:50 20:15 21:45 S. GIOVANNI ROTONDO 06:10 06:50 07:35 08:55 10:25 10:50 - 12:05 13:20 13:20 - 14:10 14:15 14:15 14:15 - 15:55 17:35 18:55 20:20 21:50 Matine 06:25 07:05 07:50 09:10 10:40 11:05 - 12:20 13:35 13:35 - - - 14:30 14:30 - 16:10 17:50 19:10 20:35 - Nappitiello 06:30 07:10 07:55 09:15 10:45 11:10 - 12:25 13:40 13:40 - - - 14:35 14:35 - 16:15 17:55 19:15 20:40 - Signoritto 06:35 07:15 08:00 09:20 10:50 11:15 - 12:30 13:45 13:45 - - - 14:40 14:40 - 16:20 18:00 19:20 20:45 - MANFREDONIA - Capitaneria 06:50 07:30 08:15 09:35 11:05 11:30 - 12:45 14:00 14:00 - - - 14:55 14:55 - 16:35 18:15 19:35 21:00 - MANFREDONIA - Bar Pace - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Cadenza fer fer scol scol FEST fer fer scol scol fer ns FEST fer fer fer fer -

ATTI PUBBLICI, N.55

ARCHIVIO DI STATO DI FOGGIA INTENDENZA DI FINANZA A T T I P U B B L I C I BustaUfficio del Registro Anni Osservazioni 1 Ascoli 1869 2 Ascoli 1870 3 Ascoli 1871 4 Ascoli 1871 5 Ascoli 1872 6 Ascoli 1872 7 Biccari 1869 8 Biccari 1870 9 Biccari 1871 10 Biccari 1872 11 Bi Bovino 1869 12 Bovino 1869 13 Bovino 1869 14 Bovino 1870 15 Bovino 1870 16 Bovino 1870 17 Bovino 1870 18 Bovino 1871 19 Bovino 1871 20 Bovino 1871 21 Bovino 1871 22 Bovino 1872 23 Bovino 1872 24 Bi Bovino 1872 25 Bovino 1872 26 Castelnuovo 1869 27 Castelnuovo 1870 28 Castelnuovo 1871 29 Castelnuovo 1871 30 Castelnuovo 1872 31 Castelnuovo 1872 32 Celenza 1869 33 Celenza 1870 34 Celenza 1871 35 Celenza 1872 36 Cerignola 1869 37 Ci Cerignola l 1869 38 Cerignola 1869 ARCHIVIO DI STATO DI FOGGIA, inventario del fondo INTENDENZA DI FINANZA, ATTI PUBBLICI BustaUfficio del Registro Anni Osservazioni 39 Cerignola 1869 40 Cerignola 1870 41 Cerignola 1870 42 Cerignola 1870 43 CerignolaCerignola 1870 44 Cerignola 1870 45 Cerignola 1871 46 Cerignola 1871 47 Cerignola 1871 48 Cerignola 1871 49 Cerignolag 1872 50 Cerignola 1872 51 Cerignola 1872 52 Cerignola 1872 53 Cerignola 1872 54 Cerignola 1872 55 Foggia 1869 56 FoggiaFoggia 1869 57 Foggia 1869 58 Foggia 1869 59 Foggia 1869 60 Foggia 1869 61 Foggia 1870 62 Foggiagg 1870 63 Foggia 1870 64 Foggia 1870 65 Foggia 1870 66 Foggia 1870 67 Foggia 1870 68 Foggia 1871 69 FoggiaFoggia 1871 70 Foggia 1871 71 Foggia 1871 72 Foggia 1871 73 Foggia 1871 74 Foggia 1871 75 Foggiagg 1871 76 Foggia 1872 77 Foggia 1872 78 Foggia 1872 79 Foggia 1872 80 -

Sistema Informativo Ministero Della Pubblica Istruzione

SMOW5A 18-04-15PAG. 1 SISTEMA INFORMATIVO MINISTERO DELLA PUBBLICA ISTRUZIONE UFFICIO SCOLASTICO REGIONALE PER LA PUGLIA UFFICIO SCOLASTICO PROVINCIALE : FOGGIA ELENCO DEI TRASFERIMENTI E PASSAGGI DEL PERSONALE DOCENTE DI RUOLO DELLA SCUOLA DELL'INFANZIA ANNO SCOLASTICO 2015/16 ATTENZIONE: PER EFFETTO DELLA LEGGE SULLA PRIVACY QUESTA STAMPA NON CONTIENE ALCUNI DATI PERSONALI E SENSIBILI CHE CONCORRONO ALLA COSTITUZIONE DELLA STESSA. AGLI STESSI DATI GLI INTERESSATI O I CONTROINTERESSATI POTRANNO EVENTUALMENTE ACCEDERE SECONDO LE MODALITA' PREVISTE DALLA LEGGE SULLA TRASPARENZA DEGLI ATTI AMMINISTRATIVI. TRASFERIMENTI NELL'AMBITO DEL COMUNE - CLASSI COMUNI 1. ALBANO MARIA ROSARIA . 29/ 7/62 (FG) DA : FGAA11000C - SAN BENEDETTO (SAN SEVERO) A : FGAA869002 - PALMIERI-S.GIOV.BOSCO-S.SEVERO (SAN SEVERO) PUNTI 88 2. ALBORETTO RIPALTA . 4/ 4/66 (FG) DA : FGAA87300N - CARDUCCI-PAOLILLO (CERIGNOLA) A : FGAA02900L - MARCONI - CERIGNOLA (CERIGNOLA) PUNTI 48 3. BUONO LOREDANA MARIA . 5/ 2/62 (FG) DA : FGAA11000C - SAN BENEDETTO (SAN SEVERO) A : FGAA11000C - SAN BENEDETTO (SAN SEVERO) DA POSTO DI SOSTEGNO MINORATI DELLA VISTA PUNTI 90 4. CELESTE ELVIRA . 24/ 7/78 (FG) DA : FGAA10600R - CD SAN FRANCESCO -S.SEVERO (SAN SEVERO) A : FGAA112004 - DE AMICIS - SAN SEVERO (SAN SEVERO) PUNTI 67 (SOPRANNUMERARIO TRASFERITO CON DOMANDA CONDIZIONATA) 5. CHINNI BRUNA LUCIANA . 19/ 1/54 (FG) DA : FGAA85600X - ALFIERI VITTORIO GARIBALDI (FOGGIA) A : FGAA85600X - ALFIERI VITTORIO GARIBALDI (FOGGIA) DA POSTO DI SOSTEGNO MINORATI FISIOPSICHICI PRECEDENZA: PREVISTA DAL C.C.N.I PUNTI 154 6. D'AMATO CINZIA MARIA . 17/ 1/70 (FG) DA : FGAA09900V - DON MILANI - TRINITAPOLI (TRINITAPOLI) A : FGAA875009 - GARIBALDI- LEONE (TRINITAPOLI) PUNTI 24 (SOPRANNUMERARIO TRASFERITO CON DOMANDA CONDIZIONATA) 7. D'EMANUELE MARIA ROSARIA . -

Consiglio Generale Degli Ospizi Bilanci Delle Opere Pie

ARCHIVIO DI STATO DI FOGGIA CONSIGLIO GENERALE DEGLI OSPIZI BILANCI DELLE OPERE PIE Numero d'ordine Anno Distretto o Comune dove si trovano gli enti di beneficenza Osservazioni del volume circondario ai quali si riferiscono i bilanci 1 1812 Foggia Foggia. 2 1812 Foggia Cerignola. 3 1812 Foggia Monte Sant'Angelo 4 1812 Foggia Manfredonia. 5 1812 San Severo Serracapriola. 6 1818 Bovino Bovino, Panni. 7 1818 Bovino Deliceto, Sant' Agata. 8 1818 Foggia Cerignola. 9 1818 Foggia Manfredonia. 10 1818 Foggia Monte Sant'Angelo 11 1822 Foggia Cerignola. 12 1822 Foggia Manfredonia. 13 1822 Foggia Monte Sant'Angelo 14 1822 Foggia Celenza, San Marco la Catola, Carlantino. 15 1822 Bovino Deliceto, Sant'Agata. 16 1822 Bovino Foggia, Volturara, Lucera, Biccari, Alberona, Roseto, Volturino, San Bartolomeo, Motta, I volumi 16-18 non sono stati discussi degli enti morali, Stornarella, Casaltrinità, Manfredonia, Vieste, Bovino, Panni, Castelluccio dei Sauri, Troia, bensì dei comuni; per tale ragione si è provveduto a Castelluccio Valmaggiore, Faeto, Anzano, Sant'Agata, Accadia, Monteleone, Ascoli, Candela, sistemarli tra gli stati discussi del 3° ufficio dell'Intendenza. Montefalcone, Greci, Ginestra, Savignano, Deliceto. Cfr. inventario del fondo Intendenza, governo e prefettura di Capitanata, Atti , b. 1073 17 1823 San Severo San Severo, Castelnuovo, Casalvecchio, Casalnuovo, Pietra, Celenza, Carlantino, San Marco la Catola, Serracapriola, Chieuti, Torremaggiore, San Paolo, Apricena, Lesina, Poggio Imperiale, Sannicandro, San Marco in Lamis, San Giovanni Rotondo, Rignano, Cagnano, Carpino, Vico, 18 1823 Bovino Candela, Accadia, Deliceto, Sant' Agata, Anzano, Monteleone, Greci, Ginestra, Montefalcone, Savignano, Castelfranco, Bovino, Panni, Faeto, Castelluccio Valmaggiore, Celle, Troia. 19 1827 Bovino Deliceto, Sant' Agata. -

All. Del Pre N. 36 10 Elenco Ditte Decreto Asserv Marco in Lamis Conc

CONSORZIO DI BONIFICA MONTANA DEL GARGANO SAN MARCO IN LAMIS N. ELENCO: 2 1 DITTA CATASTALE: NARDELLA Angela nata a San Marco in Lamis il 04.02.1922 prop. Per 1000/1000; C.F.NRDNLN22B44H985N Piazza Vitt. Veneto, 10 CASTELVETERE V.RE DATI CATASATLI IMMOBILE DA ASSERVIRE INDENNITA' N.p. Foglio Particella Qualità Superficie Superficie Coltura V.A.M. Indennità Indennità di occupazione temporanea Indennità pagata Ha. a. ca. Occupazione Occupazione €/mq. di non preordinata ad asservimento definitiva mq. temp. mq. Asservimento 1/12 annuo x 12 mesi 2 82 67 Semin. 3 00 00 902 1353 Sem. 0,84 757,68 94,71 2 82 67 Pascolo 55 58 0,00 3 82 474 Pascolo 10 02 90 135 Aia Fabb. 0,84 75,60 9,45 5 82 222 Pascolo 06 11 114 171 Pascolo 0,17 19,38 2,42 6 82 223 Pascolo 03 90 84 126 Pascolo 0,17 14,28 1,79 7 82 409 Sem. 0126 20 30 Sem. 0,84 16,80 2,10 8 82 351 Sem. 0475 100 150 Sem. 0,84 84,00 10,50 9 82 360 Sem. 0225 48 72 Sem. 0,84 40,32 5,04 13 82 69 Pasc. A. 3 58 66 660 990 Sem. 0,84 554,40 69,30 14 82 53 Pascolo 15 64 100 150 Uliveto 1,40 140,00 17,50 16 82 554 Bosco A. 01 43 50 Pasc.A. 0,15 0,00 0,63 1.915,89 CONSORZIO DI BONIFICA MONTANA DEL GARGANO N. ELENCO: 10 2 DITTA CATASTALE: GUERRIERI Anna Arcangela nata a San Marco in Lamis il 24.05.1931 prop. -

Landslides, Floods and Sinkholes in a Karst Environment

Landslides, floods and sinkholes in a karst environment: the 1-6 September 2014 Gargano event, southern Italy Maria Elena Martinotti1, Luca Pisano2,6, Ivan Marchesini1, Mauro Rossi1, Silvia Peruccacci1, Maria Teresa Brunetti1, Massimo Melillo1, Giuseppe Amoruso3, Pierluigi Loiacono3, Carmela Vennari2,4, 5 Giovanna Vessia2,5, Maria Trabace3, Mario Parise2,7, Fausto Guzzetti1 1Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Istituto di Ricerca per la Protezione Idrogeologica, via Madonna Alta 126, I-06128 Perugia, Italy 2Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Istituto di Ricerca per la Protezione Idrogeologica, via Amendola 122, I-70126 Bari, Italy 10 3Regione Puglia, Servizio di Protezione Civile, Via delle Magnolie 6/8, I-70126 Modugno (Bari), Italy 4University of Naples “Federico II”, Naples, Italy 5University of Chieti-Pescara “Gabriele D’Annunzio”, Chieti, Italy 6University of Molise, Department of Biosciences and Territory, Contrada Fonte Lappone, Pesche (IS), Italy 7Present address: University “Aldo Moro”, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Via Orabona 7, I-70126 Bari, 15 Italy Correspondence to: Maria Elena Martinotti ([email protected]) Abstract. In karst environments, heavy rainfall is known to cause multiple geo-hydrological hazards, including inundations, flash floods, landslides, and sinkholes. We studied a period of intense rainfall from 1 to 6 September 2014 in the Gargano 20 Promontory, a karst area in Puglia, southern Italy. In the period, a sequence of torrential rainfall events caused severe damage, and claimed two fatalities. The amount and accuracy of the geographical and temporal information varied for the different hazards. The temporal information was most accurate for the inundation caused by a major river, less accurate for flash floods caused by minor torrents, and even less accurate for landslides. -

CAP Località Pref

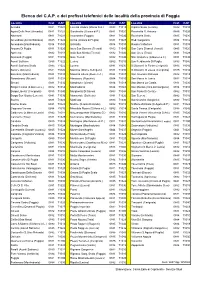

Elenco dei C.A.P. e dei prefissi telefonici delle località della provincia di Foggia Località Pref. CAP Località Pref. CAP Località Pref. CAP Accadia 0881 71021 Foresta Umbra (Monte S.A.) 0884 71018 Ripalta Scalo (Lesina) 0882 71010 Agata Delle Noci (Accadia) 0881 71021 Giardinetto (Orsara di P.) 0881 71020 Rocchetta S. Antonio 0885 71020 Alberona 0881 71031 Incoronata (Foggia) 0881 71040 Rocchetta Scalo 0885 71020 Amendola (Ascoli Satriano) 0885 71022 Ischia (Orsara di Puglia) 0881 71027 Rodi Garganico 0884 71012 Amendola (Manfredonia) 0884 71043 Ischitella 0884 71010 Roseto Valfortore 0881 71039 Anzano Di Puglia 0881 71020 Isola San Domino (Tremiti) 0882 71040 San Carlo D'ascoli (Ascoli) 0885 71020 Apricena 0882 71011 Isola San Nicola (Tremiti) 0882 71040 San Cireo (Troia) 0881 71029 Arpinova (Foggia) 0881 71010 Isole Tremiti 0882 71040 San Cristoforo (S.Marco La C.) 0881 71030 Ascoli Satriano 0885 71022 Lesina 0882 71010 San Ferdinando Di Puglia 0883 71046 Ascoli Satriano Scalo 0885 71022 Lucera 0881 71036 S.Giovanni In Fonte (Cerignola) 0885 71042 Barone Deliceto) 0881 71026 Macchia (Monte S.Angelo) 0884 71030 S.Giovanni In Zezza (Cerignola) 0885 71042 Beccarini (Manfredonia) 0884 71043 Macchia Libera (Monte S.A.) 0884 71037 San Giovanni Rotondo 0882 71013 Berardinone (Biccari) 0881 71032 Manacore (Peschici) 0884 71010 San Marco In Lamis 0882 71014 Biccari 0881 71032 Mandrione (Vieste) 0884 71019 San Marco La Catola 0881 71030 Borgo Celano (S.Marco in L.) 0882 71014 Manfredonia 0884 71043 San Menaio (Vico del Gargano) 0884 71010 Borgo -

Actes Dont La Publication Est Une Condition De Leur Applicabilité)

30 . 9 . 88 Journal officiel des Communautés européennes N0 L 270/ 1 I (Actes dont la publication est une condition de leur applicabilité) RÈGLEMENT (CEE) N° 2984/88 DE LA COMMISSION du 21 septembre 1988 fixant les rendements en olives et en huile pour la campagne 1987/1988 en Italie, en Espagne et au Portugal LA COMMISSION DES COMMUNAUTÉS EUROPÉENNES, considérant que, compte tenu des donnees reçues, il y a lieu de fixer les rendements en Italie, en Espagne et au vu le traité instituant la Communauté économique euro Portugal comme indiqué en annexe I ; péenne, considérant que les mesures prévues au présent règlement sont conformes à l'avis du comité de gestion des matières vu le règlement n0 136/66/CEE du Conseil, du 22 grasses, septembre 1966, portant établissement d'une organisation commune des marchés dans le secteur des matières grasses ('), modifié en dernier lieu par le règlement (CEE) A ARRÊTÉ LE PRESENT REGLEMENT : n0 2210/88 (2), vu le règlement (CEE) n0 2261 /84 du Conseil , du 17 Article premier juillet 1984, arrêtant les règles générales relatives à l'octroi de l'aide à la production d'huile d'olive , et aux organisa 1 . En Italie, en Espagne et au Portugal, pour la tions de producteurs (3), modifié en dernier lieu par le campagne 1987/ 1988 , les rendements en olives et en règlement (CEE) n° 892/88 (4), et notamment son article huile ainsi que les zones de production y afférentes sont 19 , fixés à l'annexe I. 2 . La délimitation des zones de production fait l'objet considérant que, aux fins de l'octroi de l'aide à la produc de l'annexe II . -

Soccio Maria Maddalena, Nata a San Marco in Lamis (FG)

Curriculum vitae Soccio Maria Maddalena P.E.C. [email protected] Titoli di studio e specializzazioni post – universitari • 1972 - Diploma di Maturità classica conseguito presso il Liceo classico “Pietro Giannone “ di San Marco in Lamis • 1976 – Laurea in Giurisprudenza conseguita presso l’Università degli studi di Napoli in data 21/10 1976, con votazione 110/110 e lode • 1978 – Abilitazione all’esercizio della professione di Procuratore Legale,( oggi avvocato) conseguita presso la Corte di Appello di Napoli • 1978 – Diploma del Corso di studi per aspiranti segretari comunali conseguito presso la Libera Università internazionale degli Studi Sociali Pro Deo di Roma( oggi LUISS) con votazione 56,5/60 • 1979 – Corso di perfezionamento in Scienze Amministrative presso l’università degli studi “ La Sapienza” di Roma con votazione 30/30 e lode • 2006- SSPAL- SE.F.A. III- novembre 2005/febbraio 2006. Corso di specializzazione per idoneità a segretario generale nei comuni con oltre 65.000 abitanti, capoluogo di provincia e province ( art. 14, comma 2,D.P.R. 465/1997) Altri corsi di formazione e specializzazione • 1981- Corso di perfezionamento per Segretari comunali e provinciali Ministero Interno • 1985- Corso di perfezionamento per Segretari comunali e provinciali –Prefettura di Foggia • 1991- Corso di perfezionamento per Segretari comunali e provinciali –Prefettura di Foggia • 1992- Corso aggiornamento per Segretari comunali e provinciali – Prefettura di Foggia • 1992- Corso “ esperti nelle tecniche di gestione delle attività contrattuali Pubbliche per gli enti locali della provincia di Foggia” organizzato dal FORMEZ di Napoli • 2000- Corso di aggiornamento S.S.P.A.L. “ Progetto Merlino” relativo alla formazione e conoscenza di tecniche direzionali • 2001- Corso di formazione del “ Progetto PASS SAN SEVERO “ relativo alla costituzione di una rete civica intercomunale a supporto dei servizi dei cittadini e delle imprese • 2001- S.S.P.A.L. -

ITA Enti Adempienti

Elenco degli Enti locali e territoriali che hanno comunicato nell'ultimo biennio i dati relativi all'indebitamento ai sensi di quanto disposto dall'art.1 - comma 1 del Decreto 01/12/2003 n. 389.