University of Warwick Institutional Repository: a Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Phd at The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caribbean Voices Broadcasts

APPENDIX © The Author(s) 2016 171 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 TIMELINE OF THE BBC CARIBBEAN VOICES BROADCASTS March 11th 1943 to September 7th 1958 © The Author(s) 2016 173 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 TIMELINE OF THE BBC CARIBBEAN VOICES EDITORS Una Marson April 1940 to December 1945 Mary Treadgold December 1945 to July 1946 Henry Swanzy July 1946 to November 1954 Vidia Naipaul December 1954 to September 1956 Edgar Mittelholzer October 1956 to September 1958 © The Author(s) 2016 175 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 TIMELINE OF THE WEST INDIES FEDERATION AND THE TERRITORIES INCLUDED January 3 1958 to 31 May 31 1962 Antigua & Barbuda Barbados Dominica Grenada Jamaica Montserrat St. Kitts, Nevis, and Anguilla St. Lucia St. Vincent and the Grenadines Trinidad and Tobago © The Author(s) 2016 177 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 CARIBBEAN VOICES : INDEX OF AUTHORS AND SEQUENCE OF BROADCASTS Author Title Broadcast sequence Aarons, A.L.C. The Cow That Laughed 1369 The Dancer 43 Hurricane 14 Madam 67 Mrs. Arroway’s Joe 1 Policeman Tying His Laces 156 Rain 364 Santander Avenue 245 Ablack, Kenneth The Last Two Months 1029 Adams, Clem The Seeker 320 Adams, Robert Harold Arundel Moody 111 Albert, Nelly My World 496 Alleyne, Albert The Last Mule 1089 The Rock Blaster 1275 The Sign of God 1025 Alleyne, Cynthia Travelogue 1329 Allfrey, Phyllis Shand Andersen’s Mermaid 1134 Anderson, Vernon F. -

Pablo Bio-Bibliographical Sketch

Lubitz' TrotskyanaNet Michel Pablo Bio-Bibliographical Sketch Contents: Basic biographical data Biographical sketch Selective bibliography Basic biographical data Name: Michel Pablo Other names (by-names, pseud. etc.): Abdelkrim ; Alain ; Archer ; Gabe ; Gabriel ; Henry ; Jérôme ; J.P. Martin ; Jean-Paul Martin ; Mike; Molitor ; M.P. ; Murat ; Pilar ; Michalēs N. Raptēs ; Michel Raptis ; Mihalis Raptis ; Mikhalis N. Raptis ; Robert ; Smith ; Spero ; Speros ; Vallin Date and place of birth: August 24, 1911, Alexandria (Egypt) Date and place of death: February 17, 1996, Athens (Greece) Nationality: Greek Occupations, careers, etc.: Civil engineer, professional revolutionary Time of activity in Trotskyist movement: 1928 - 1964 (1995) Biographical sketch A lifelong revolutionary, Michel Pablo for some one and a half decades was the chief leader of the Trotskyist Fourth International – or at least of its majority faction. He was perhaps one of the most renowned and at the same time one of the most controversial figures of the international Trotskyist movement; for all those claiming for themselves the label of "orthodox" Trotskyism, Pablo since 1953 was a whipping boy and the very synonym for centrism, revisionism, opportunism, and even for liquidationism. 'Michel Pablo' is one (and undoubtedly the best known) of more than about a dozen pseudonyms used by a man who was born Michael Raptis [Mikhalēs Raptēs / Μισέλ Πάμπλο]1 as son of Nikolaos Raptis [Raptēs], a Greek civil engineer, in Alexandria (Egypt) on August 24, 1911. He grew up and attended Greek schools in Egypt and from 1918 in Crete before, at the age of 17, he moved to Athens enrolling at the Polytechnic where he studied engineering. -

Society for Caribbean Studies 42Nd Annual Conference Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, University of London, 4-6 July, 2018 Programme

Society for Caribbean Studies 42nd Annual Conference Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, University of London, 4-6 July, 2018 Programme Wednesday 4th July Room Lecture theatre L101 L102 Registration outside the lecture theatre from 11am Please note that no lunch is provided on this day 12.30-1.30 Chair’s welcome and Keynote Presentation: Professor Bill Schwarz, Queen Mary University of London. Title: TBA 1.30 Tea and Coffee Break L03/04 2.00-4.00 Visual translations: art, (Geo)politics Feeling and family: film and writing love, care, passion and policy 4.00 Tea and Coffee Break L03/04 4.30–6.30 Surveying Caribbean Conflicting Memories: The Eastern Caribbean: Outposts, 1924 to 1943 Cross-border Religion, Diaspora, and displacements, and the Archive climate change 6.30 Bridget Jones Award Presentation - Katie Numi Usher 7.30 Buffet Dinner: Chancellors Hall Thursday 5th July Room Lecture theatre L101 L102 9.00–11.00 Writing history Re-reading writers: Changing responses to differently: writing juxtapositions and climate change different histories 1 relocations 11.00 Tea and Coffee Break L03/04 11.30–1.00 Ideologies of race in Circulating forms: Money, business and Cuba print, folk, literature economics 1.00 Lunch L03/04 2.00–3.30 Sonic cultures Caribbean literature in Landscapes of the classroom language and discourse 3.30 Tea and Coffee Break L03/04 4.00-5.30 Carnival cultures Writing history differently: writing different histories 2 5.30-6.30 AGM 6.30–7.30 Rum Punch Reception, including a short presentation by Dr Elizabeth Cooper, Curator of the British Library’s Latin American and Caribbean collections, about the British Library’s exhibition ‘Windrush: Songs in a Strange Land’; and a poetry performance by Keith Jarrett. -

Making History – Alex Callinicos

MAKING HISTORY HISTORICAL MATERIALISM BOOK SERIES Editorial board PAUL BLACKLEDGE, London - SEBASTIAN BUDGEN, London JIM KINCAID, Leeds - STATHIS KOUVELAKIS, Paris MARCEL VAN DER LINDEN, Amsterdam - CHINA MIÉVILLE, London WARREN MONTAG, Los Angeles - PAUL REYNOLDS, Lancashire TONY SMITH, Ames (IA) MAKING HISTORY Agency, Structure, and Change in Social Theory BY ALEX CALLINICOS BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2004 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Callinicos, Alex. Making history : agency, structure, and change in social theory / Alex Callinicos – 2nd ed. p. cm. — (Historical materialism book series, ISSN 1570-1522 ; 3) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 90-04-13627-4 (alk. paper) 1. Agent (Philosophy) 2. Act (Philosophy) 3. Structuralism. 4. Historical materialism. 5. Revolutions—Philosophy. 6. Marx, Karl, 1818-1883. I. Title. II. Series. BD450.C23 2004 128’.4—dc22 2004045143 second revised edition ISSN 1570-1522 ISBN 90 04 13827 4 © Copyright 2004 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. PRINTED IN THE NETHERLANDS To John and Aelda Callinicos This page intentionally left blank Contents Preface ............................................................................................................ ix Introduction to the Second Edition ............................................................ xiii Introduction ................................................................................................... -

J. Dillon Brown One Brookings Drive, Campus Box 1122 St

J. Dillon Brown One Brookings Drive, Campus Box 1122 St. Louis, MO 63130 (314) 935-9241 [email protected] Appointments 2014-present Associate Professor of Anglophone Literatures Department of English, African and African American Studies Program Washington University in St. Louis 2007-2014 Assistant Professor of Anglophone Literatures Department of English, African and African American Studies Program Washington University in St. Louis 2006-2007 Assistant Professor of Diaspora Studies English Department Brooklyn College, City University of New York Education 2006 Ph.D. in English Literature, University of Pennsylvania 1994 B.A. in English Literature, University of California, Berkeley Fellowships, Grants, Awards Summer 2013 Arts and Sciences Research Seed Grant (Washington University) Spring 2013 Center for the Humanities Faculty Fellowship (Washington University) 2011 Common Ground Course Development Grant (Washington University) 2009 Harry S. Ransom Center British Studies Fellowship 2009 Special Recognition for Excellence in Graduate Student Mentoring Summer 2007 PSC CUNY Research Award 2006-2007 Brooklyn College New Faculty Fund Award 2006-2007 Leonard & Clare Tow Faculty Travel Fellowship (Brooklyn College) 2004-2005 J. William Fulbright Research Grant (for Barbados and Trinidad & Tobago) Books Migrant Modernism: Postwar London and the West Indian Novel Monograph examining the metropolitan origins of early West Indian novels with an interest in establishing the historical, social, and cultural contexts of their production. Through individual case studies of George Lamming, Roger Mais, Edgar Mittelholzer, V.S. Naipaul, and Samuel Selvon, the book seeks to demonstrate Caribbean fiction’s important engagements with the experimental tradition of British modernism and discuss the implications of such engagements in terms of understanding the nature, history, locations, and legacies of both modernist and postcolonial literature. -

Annual Report 2015–2016

THE NATIONAL HUMANITIES CENTER ANNUAL REPORT 2015-2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 Report from the President and Director 8 Scholarly Programs Work of the Fellows Statistics Books by Fellows 30 Education Programs 32 Public Engagement 34 Highlights of the Year 36 Financial Statements 38 Supporting the Center Center Supporters The National Humanities Center does Annual Giving Summary not discriminate on the basis of race, color, sex, gender identity, religion, national and ethnic origin, sexual orientation or preference, or age in the administration 44 Staff of the Center of its selection policies, educational policies, and other Center-administered programs. 45 Board of Trustees Editor Donald Solomon Images Joel Elliott Design Barbara Schneider The National Humanities Center’s Report (ISSN 1040-130X) is printed on recycled paper. Copyright ©2016 by National Humanities Center 7 T.W. Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256, RTP, NC 27709-2256 Tel 919-549-0661 Fax 919-990-8535 Email: [email protected] Website: nationalhumanitiescenter.org The humanities encourage a culture of rigor, pluralism, innovation, and evidence. As long as these values are maintained in our processes and products, the shape our work takes, the audiences it reaches, and the valuation it receives benefit from a healthy multiplicity and a resistance to static definitions and one-dimensional accountability. – Robert D. Newman REPORT FROM THE PRESIDENT & DIRECTOR When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer When I heard the learn’d astronomer, When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me, When I was shown the charts and diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them, When I sitting heard the astronomer where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room, How soon unaccountable I became tired and sick, Till rising and gliding out I wander’d off by myself, In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time, Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars. -

Andthe Anarchists Other Issues of "Anarchy"L Gontents of Il0

AilARCHYJ{0.109 3shillings lSpence 40cents "-*"*"'"'r ,Eh$ Russell andthe Anarchists Other issues of "Anarchy"l Gontents of il0. 109 Please note that the following issues are out of print: I to 15 inclusive, 26,27, 38, ANiARCHY 109 (Vol l0 No 3) MARCH 1970 65 March 1970 39, 66, 89, 90, 96, 98, 102. Vol. I 1961l. 1. Sex-and-Violence; 2. Workers' control; 3. What does anar- chism mcarr today?: 4. Deinstitutioni- sariorr; 5. Spain; 6. Cinema; 7. Adventure playgrourrd; 3. Anthropology; 9. Prison; 10. [ndustrial decentralisation. Neither God nor Master V. Ncill; 12. Who are the anarchists?; 13. Richard Drinnon 65 Direct action; 14. Disobcdience; 15. David Wills; 16. Ethics of anarchism; 17. Lum- lleilther God pcn proletariat ; I {l.Comprehensive schools; Russell and the anarchists 19. 'Ihcatrc; 20. Non-violence; 21. Secon- dary Vivian Harper 68 modern; 22. Marx and Bakunin. nor Master Vol. 3. l96f : 23. Squatters; 24. Com- murrity of scholars; 25. Cybernetics; 26. RIOHABD DNIililOI{ Counter-culture 'l'horcarri 27. Yor-rth; 28. Future of anar- chisml 2t). Spies for peace;30. Com- Kingsley lAidmer 18 rnurrity workshop; 31. Self-organising systcmsi 32. Orimc; 33. Alex Comfort; Kropotkin and his memoirs J4. Scicnce fiction. Nicolas Walter 84 .17. I won't votc; 38. Nottingham; 39. Tsoucn ITS Roors ARE DBEpLy BURIED, modern anarchism I Iorncr l-ancl 40. Unions; 41. Land; dates from the entry of the Bakuninists into the First Inter- 42. India; 43. Parents and teachers; 44, Observations on eNanttnv 104 l'rarrsport; 45. Thc Greeks;46. Anarchisrn national just a hundred years ago. -

Chinua Achebe and James Baldwin

ESSAY After Decolonization, After Civil Rights: Chinua Achebe and James Baldwin Bill Schwarz Queen Mary University of London Abstract The escalation of systematic, if random, violence in the contemporary world frames the concerns of the article, which seeks to read Baldwin for the present. It works by a measure of indirection, arriving at Baldwin after a detour which introduces Chinua Achebe. The Baldwin–Achebe relationship is familiar fare. However, here I explore not the shared congruence between their first novels, but rather focus on their later works, in which the reflexes of terror lie close to the surface. I use Achebe’s final novel, Anthills of the Savanah, as a way into Baldwin’s “difficult” last book, The Evidence of Things Not Seen, suggesting that both these works can speak directly to our own historical present. Both Baldwin and Achebe, I argue, chose to assume the role of witness to the evolving mani- festations of catastrophe, which they came to believe enveloped the final years of their lives. In order to seek redemption they each determined to craft a prose—the product of a very particular historical conjuncture—which could bring out into the open the prevailing undercurrents of violence and terror. Keywords: James Baldwin, Chinua Achebe, decolonization, U.S. civil rights, literature, terror, redemption We have lost the twentieth century; are we bent on seeing that our children also lose the twenty-first? God forbid. Chinua Achebe, 1983.1 Fanaticism. The One Way, One Truth, One Life menace. The Terror that lives completely alone. Chinua Achebe, 1993.2 To counter “racial terror” we require “a ruthless cunning, an impenetrable style, and an ability to carry death, like a bluebird, on the shoulder.” James Baldwin, 1985.3 James Baldwin Review, Volume 1, 2015 © The Authors. -

What Happened to the Workers' Socialist League?

What Happened to the Workers’ Socialist League? By Tony Gard (as amended by Chris Edwards and others), September 1993 Note by Gerry D, October 2019: This is the only version I have of Tony Gard’s docu- ment, which contains the unauthorised amendments as explained in the rather tetchy note by Chris Edwards below. [Note by Chris Edwards (May 2002). War is the sternest possible test for any Trot- skyist organisation. While many British organisations failed this test in the case of the Malvinas/Falklands War (e.g. the Militant group with its “workers war” against Argen- tina position), the British proto-ITO comrades did attempt to defend a principled posi- tion against the bankrupt positions of the leadership of their own organisation, the British Workers Socialist League (WSL). This is an account of the tendency struggle over the Malvinas war and many other is- sues to do with British imperialism. This document was written with the stated purpose of being a “balance sheet” of the tendency struggle. It was somewhat ironic that, Tony G, the author of most of this document, and the person who had played the least part in the WSL tendency struggle during 1982-3, felt himself most qualified to sit in judge- ment on the efforts of those who had been centrally involved in the tendency struggle. This was despite his insistence that he did not wish to do so at the beginning of this ac- count (see below). In fact, one of the barely disguised purposes of this “balance sheet” was to rubbish and belittle the efforts of the comrades who had been centrally involved in the tendency struggle. -

Memories on a Monday: Peace Monday 11 May 2020

Memories on a Monday: Peace Monday 11 May 2020 Welcome to Memories on a Monday: Peace - sharing our heritage from Bruce Castle Museum & Archive. Following the commemorative events last week of VE Day, we turn now to looking at some of the ways we have marked peace in our communities in Haringey, alongside the strong heritage of the peace movement and activism in the borough. In July 2014, a memorial was unveiled alongside the woodland in Lordship Recreation Ground in Tottenham. Created by local sculptor Gary March, the sculpture shows two hands embracing a dove, the symbol of peace. Its design and installation followed a successful a campaign initiated by Ray Swain and the Friends of Lordship Rec to dedicate a permanent memorial to over 40 local people who tragically lost their lives in September 1940. They died following a direct hit by a high-explosive bomb falling on the Downhills public air raid shelter. It was the highest death toll in Tottenham during the Second World War. (You can see the sculpture and read more about this tragedy here and also here from the Summerhill Road website). Three years before, in Stroud Green, a Peace Garden was named and unveiled in 2011. It commemorates the 15 people who died, 35 people who were seriously injured, the destruction of 12 houses and the severe damage of Holy Trinity Church and 100 other homes in the area. The details below, can be read on the attached PDF. The Peace Garden Board can be found in the garden, at the junction where Stapleton Hall Road meets Granville Road, N4. -

Quaker Thought and Life Today

Quaker Thought and Life Today VOWMI 9 JULY 15, 1963 NUMBER 14 C!)f: puff and wheeze, we struggle and discuss. We have A Meeting's Creative Experience endless committee meetings. But j esus said where two or A Committee's Report three meet in my name I am there in the midst, and then they grow like the lily or the tree by the brook. I t isn't Letter from England effort, it isn't struggle that makes persons grow. It is life. by Colin Fawcett It is contact with the forces of life that does it. Growth is silent, gentle, quiet, unnoticed, but you can't have growth un Good Words for Love's Fools til you have the miracle of life and until it is in contact with by Sam Bradley the sources and the forces of life-soil, sun, water, and air. - R uFus M. JoNEs 1863 Bright-Churchill 1963 A Letter from the Past TWENTY· FIVE CENTS $5.00 A YEAR Under the Red and Black Star 306 FRIENDS JOURNAL July 15, 1963 FRIENDS JOURNAL UNDER THE RED AND BLACK STAR AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE Lahsin Plants a Tree ORMALLY on Thursday afternoons Lahsin Hajar, N a 10-year-old Algerian boy, can be found in the carpentry workshop of the Quaker Center at Souk el Tleta, working on a bench he is making. Today, however, Published semimonthly, on the first and fifteenth of each month, at 1515 Cherry Street, Philadelphia 2, Penn he has been picked by the Quaker agriculturalist to sYlvania (LO 3-7669) by Friends Publishing Corporation. -

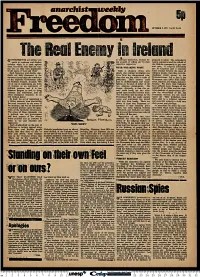

Standing on Their Own Feet Or on Ours?

anarchistmmweehly Vol 32 No 31 riOVERNMENTS are always very to extricate themselves, without be- prepared to admit. The campaign is quick to condemn and deplore ing accused of 'selling out' by their mainly centred around the refusal of ' violence when it is used against respective supporters. the Catholic community to pay rent them, but all the time they are wag- *2? and rates. If religious differences ing war on their own populations NEAR BREAKING POINT can be forgotten and a common in the name of 'Law and Order'. Such a situation shows \pry bond created between the mass of Such hypocrisy and double stan- clearly that nothing worthwhile can ordinary people, then this civil dis- dards are fully illustrated in the come from the compromised solu- obedience could spread to the statement issued after the conclusion tions that are the stock in trade of Protestant areas. Let us face it, the of the tripartite Government talks politicians. Their answers could Protestants also suffer from indig- on Northern Ireland. It reads: 'We lead to disillusionment and resent- nities, injustice, low wages, and poor are at one in condemning any form *SpV '■"■ t •■■■•.-•>a*-v.tv13fc:V-J~. ■ '. ¥r \£-\. ■':'<*.^^!.^/'Ui/^jKjp,-ki,f-^AJi^ fulness on the part of either of the . housing. We know that Catholics of violence as an instrument of il'*;(»»'>,i,^'lk"'f-l<*. -»fr''^ . Vt'/i'li'/-- 1 '' '*■ ■''■**4fflv- ■ ' V'^&f«Ufl*?tivr r two religious communities. The have suffered more because of the political pressure and it is our danger, obviously, is that this en- inability of the State and the capi- common purpose to seek to bring mity could break out into wide- talist methods of production to pro- violence and internment, and all spread open hostility between them.