Managing Mitchelli Grass a Grazier's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHARLEVILLE FLOOD MANAGEMENT – MOVING BEYOND MITIGATION Murweh Shire, Queensland Town of Charleville, Murweh Shire, Queensland

6/4/2014 Neil Polglase David Murray Murweh Shire, Queensland May 2014 • Land area of 43,905 km 2 CHARLEVILLE FLOOD MANAGEMENT – • Population MOVING BEYOND MITIGATION – Murweh Shire – 4,910 – Town of Charleville – 3,278 Emergency Management System – Town of Augathella - 500 • Temperatures – 15 oC to 37 oC during the summer months – 3oC to 25 oC during the winter months • Wet season is typically January through April The Warrego River Overtopped its Banks in Town of Charleville, Murweh Shire, April 1990 and February 1997 with Little Queensland Australia Warning In Response to 1990 and the 1997 Flooding, a In March 2010 the Town Floods Again via Levee along Warrego River was Constructed Bradley’s Gully Tributary 1 6/4/2014 Following the 2010 Flood, Queensland In February 2012 –Levee Saves Charleville From Government Funded Two Additional Flood Second Biggest Flood of Record Mitigation Projects • Construction of a second levee along Bradley’s Gully • Project for flood and fire response planning Warrego River Bradley’s Gully Five Major Floods were Recorded Since 1990 Emergency Management System • CDM Smith was selected to meet with Stakeholders and Event Estimated Peak Location Flood Mechanism develop approach to meet their needs (year) Discharge (m 3/s) • First task order included: November 2012 – February 2013 Warrego River 1990 5470 No Levee – Major Warrego River Flooding at Charleville – Onsite visit to review historical data & meet with stakeholders No Levee – Repeat of significant Warrego River 1997 2180 Flooding – Collect relevant data -

Murweh Shire Council

MURWEH SHIRE COUNCIL LONG TERM COMMUNITY PLAN 2012 – 2022 Shaping the Future of the communities of Augathella, Charleville, Morven and the Rural Sector 0 1 REGION OVERVIEW: The local government area of Murweh Shire has a total area of 40,774.5 km2, or 2.4 per cent of the total area of the state. The region has an average daily temperature range of 13.1oC to 28.0oC and on average Murweh Shire receives 510 mm of rainfall each year. Demography: As at 30 June 2010, the estimated resident population of Murweh Shire was 4,910 persons, or 0.1 per cent of the state's population. Murweh Shire's population in 2031 is projected to be 4,804 persons. At the time of the 2006 Census, in Murweh Shire, 37.7 per cent of persons were living (usually residing) at a different address five years earlier. At the time of the 2006 Census, there were 5.3 per cent of persons in Murweh Shire who stated they were born overseas. Society: At the time of the 2006 Census, there were 3.9 per cent of persons in need of assistance with a profound or severe disability in Murweh Shire. At the time of the 2006 Census, there were 25.6 per cent of persons aged 15 years and over who were volunteers in the Murweh Shire. As at 30 June 2009 in Murweh Shire, there were 2 aged-care service providers, with a total of 60 places in operation. Economic Performance: At the time of the 2006 Census, Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing was the largest industry of employment for Murweh Shire usual residents, with 19.0 per cent of the region's employed labour force. -

Learning Technology Programs in an Isolated Region: Classroom Applications of Technology. PUB DATE 93 NOTE 15P.; In: Rural Education Issues: an Australian Perspective

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 365 500 RC 019 455 AUTHOR Hughes, Carol TITLE Learning Technology Programs in an Isolated Region: Classroom Applications of Technology. PUB DATE 93 NOTE 15p.; In: Rural Education Issues: An Australian Perspective. Key Papers Number 3; see RC 019 452. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Access to Education; Computer Literacy; *Computer Uses in Education; *Distance Education; Educational Technology; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Geographic Isolation; *Information Technology; Postsecondary Education; *Rural Education; Small Schools; Telecommunications IDENTIFIERS *Australia (Queensland) ABSTRACT This paper describes computer and distance-education technologies in the South Western Educational Region of Queensland (Australia). The South Western Region is characterized by isolation, small schools, high teacher and principal turnover, teacher and principal inexperience, student mobility, pockets of social and economic deprivation, and many students of aboriginal origin. For the past 2 years, advancements in the region's educational technology has been dominated by the Queensland Department of Education Learning Systems Project. The project encompasses: (1) establishment of business education centers in secondary schools, focusing on use of computers and other modern business technologies;(2) implementation of electronic learning centers in primary and secondary schools; (3) introduction of a practical computer methods course into years 11 and 12;(4) installation and establishment of telelearning sites in remote areas, thereby greatly expanding curriculum options; and (5) extensive professional development for classroom teachers and school communities. Regional initiatives have provided equipment and training related to electronic communication since 1987, supplied facsimile machines to all of the smallest and most isolated schools, and created an integrated program for the repair and maintenance of all computer hardware and accessories. -

Resilience, Vulnerability and Adaptive Capacity of an Inland Rural Town Prone to flooding: a Climate Change Adaptation Case Study of Charleville, Queensland, Australia

Nat Hazards (2011) 59:699–723 DOI 10.1007/s11069-011-9791-y ORIGINAL PAPER Resilience, vulnerability and adaptive capacity of an inland rural town prone to flooding: a climate change adaptation case study of Charleville, Queensland, Australia Diane U. Keogh • Armando Apan • Shahbaz Mushtaq • David King • Melanie Thomas Received: 5 July 2010 / Accepted: 15 March 2011 / Published online: 29 March 2011 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011 Abstract Australia is currently experiencing climate change effects in the form of higher temperatures and more frequent extreme events, such as floods. Floods are its costliest form of natural disaster accounting for losses estimated at over $300 million per annum. This article presents an historical case study of climate adaptation of an Australian town that is subject to frequent flooding. Charleville is a small, inland rural town in Queensland situated on an extensive flood plain, with no significant elevated areas available for relocation. The study aimed to gain an understanding of the vulnerability, resilience and adaptive capacity of this community by studying the 2008 flood event. Structured ques- tionnaires were administered in personal interviews in February 2010 to householders and businesses affected by the 2008 flood, and to institutional personnel servicing the region (n = 91). Data were analysed using appropriate quantitative and qualitative techniques. Charleville was found to be staunchly resilient, with high levels of organisation and cooperation, and well-developed and functioning social and institutional networks. The community is committed to remaining in the town despite the prospect of continued future flooding. Its main vulnerabilities included low levels of insurance cover (32% residents, 43% businesses had cover) and limited monitoring data to warn of impending flooding. -

Regional-Map-Outback-Qld-Ed-6-Back

Camooweal 160 km Burke and Wills Porcupine Gorge Charters New Victoria Bowen 138° Camooweal 139° 140° 141° Quarrells 142° 143° Marine fossil museum, Compton Downs 144° 145° 146° Charters 147° Burdekin Bowen Scottville 148° Roadhouse 156km Harrogate NP 18 km Towers Towers Downs 80 km 1 80 km 2 3 West 4 5 6 Kronosaurus Korner, and 7 8 WHITE MTNS Warrigal 9 Milray 10 Falls Dam 11 George Fisher Mine 139 OVERLANDERS 48 Nelia 110 km 52 km Harvest Cranbourne 30 Leichhardt 14 18 4 149 recreational lake. 54 Warrigal Cape Mt Raglan Collinsville Lake 30 21 Nonda Home Kaampa 18 Torver 62 Glendower NAT PARK 14 Biralee INDEX OF OUTBACK TOWNS AND Moondarra Mary Maxwelton 32 Alston Vale Valley C Corea Mt Malakoff Mt Bellevue Glendon Heidelberg CLONCURRY OORINDI Julia Creek 57 Gemoka RICHMOND Birralee 16 Tom’s Mt Kathleen Copper and Gold 9 16 50 Oorindi Gilliat FLINDERS A 6 Gypsum HWY Lauderdale 81 Plains LOCALITIES WITH FACILITIES 11 18 9THE Undha Bookin Tibarri 20 Rokeby 29 Blantyre Torrens Creek Victoria Downs BARKLY 28 Gem Site 55 44 Marathon Dunluce Burra Lornsleigh River Gem Site JULIA Bodell 9 Alick HWY Boree 30 44 A 6 MOUNT ISA BARKLY HWY Oonoomurra Pymurra 49 WAY 23 27 HUGHENDEN 89 THE OVERLANDERS WAY Pajingo 19 Mt McConnell TENNIAL River Creek A 2 Dolomite 35 32 Eurunga Marimo Arrolla Moselle 115 66 43 FLINDERS NAT TRAIL Section 3 Outback @ Isa Explorers’ Park interprets the World Rose 2 Torrens 31 Mt Michael Mica Creek Malvie Downs 52 O'Connell Warreah 20 Lake Moocha Lake Ukalunda Mt Ely A Historic Cloncurry Shire Hall, 25 Rupert Heritage listed Riversleigh Fossil Field and has underground mine tours. -

2021 Land Valuations Overview Murweh

Land valuations overview: Murweh Shire Council On 31 March 2021, the Valuer-General released land valuations for 2,358 properties with a total value of $508,701,560 in the Murweh Shire Council area. The valuations reflect land values at 1 October 2020 and show that Murweh Shire has increased by 75 per cent overall since the last valuation in 2018. Rural land values have increased significantly due to the strength in beef commodity prices as well as a low interest rate environment. Due to the decline in western towns and the effects of a prolonged drought, residential values in Charleville have experienced moderate to significant reductions. Inspect the land valuation display listing View the valuation display listing for Murweh Shire Council online at www.qld.gov.au/landvaluation or visit the Department of Resources, Hood Street, Charleville. Detailed valuation data for Murweh Regional Council Valuations were last issued in the Murweh Shire Council area in 2018. Property land use by total new value Residential land Table 1 below provides information on median values for residential land within the Murweh Shire Council area. Table 1 - Median value of residential land Residential Previous New median Change in Number of localities median value value as at median value properties as at 01/10/2020 (%) 01/10/2017 ($) ($) Augathella 4,700 4,700 0.0 166 Bakers Bend 200 200 0.0 1 Charleville 12,200 9,800 -19.7 1,296 Cooladdi 3,000 3,000 0.0 2 Langlo 750 750 0.0 2 Morven 11,200 13,500 20.5 96 All residential 12,000 9,600 -20.0 1,563 localities Explanatory Notes: The town of Charleville has generally experienced moderate reductions in residential lands. -

Queensland-Map.Pdf

PAPUA NEW GUINEA Darwin . NT Thursday Island QLD Cape York WA SA . Brisbane Perth . NSW . Sydney Adelaide . VIC Canberra . ACT Melbourne TAS . Hobart Weipa PENINSULA Coen Queensland Lizard Is DEVELOPM SCALE 0 10 20 300km 730 ENT Kilometres AL Cooktown DEV 705 ROAD Mossman Port Douglas Mornington 76 Island 64 Mareeba Cairns ROAD Atherton A 1 88 Karumba HWY Innisfail BURKE DY 116 Normanton NE Burketown GULF Tully DEV RD KEN RD Croydon 1 194 450 Hinchinbrook Is WILLS 1 262 RD Ingham GREGOR 262 BRUCE Magnetic Is DEV Y Townsville DEV 347 352 Ayr Home Hill DE A 1 Camooweal BURKE A 6 130 Bowen Whitsunday 233 Y 188 A Charters HWY Group BARKL 180 RD HIGHW Towers RD Airlie Beach Y A 2 Proserpine Y Cloncurry FLINDERS Richmond 246 A 7 396 R 117 A 6 DEV Brampton Is Mount Isa Julia Creek 256 O HWY Hughenden DEV T LANDSB Mackay I 348 BOWEN R OROUGH HWY Sarina R A 2 215 DIAMANTINA KENNEDY E Dajarra ROAD DOWNS T 481 RD 294 Winton DEV PEAK N 354 174 GREG A 1 R HIGHW Clermont BRUCE E KENNEDY Boulia OR 336 A A 7 H Y Y Yeppoon DEV T Longreach Barcaldine Emerald Blackwater RockhamptonHeron Island R A 2 CAPRICORN A 4 HWY HWY 106 A 4 O RD 306 266 Gladstone N Springsure A 5 A 3 HWY 389 Lady Elliot Is LANDSBOR HWY DAWS Bedourie Blackall ON Biloela 310 Rolleston Moura BURNETT DIAMANTINA OUGH RD A 2 C 352 Bundaberg A 404 R N Theodore 385 DEV A Hervey Bay R 326 Eidsvold A 1 V LEICHHARDT Fraser Is D O Windorah E Taroom N 385 V BRUCE EYRE E Augathella Maryborough L Gayndah RD HWY A 3 O DEV A 7 A 5 HWY Birdsville BIRDSVILLE 241 P M HWY A 2 E N W T ARREGO AL Gympie Quilpie -

The Pulse April 2021

South West Hospital and Health Service APRIL 2021 EDITION From the Board Chair 3 Our Teams 19 Board out and about 4 Palliative care streaming into remote homes 19 From the Chief Executive 7 TRAIC Grazing Futures 19 Our Communities 8 First Nations tackle flu 8 Our Services 20 Surat partnerships support early Lymphoedema training for South West clinicians 20 childhood development 8 Roma’s Rehabilitation area supporting South West HHS COVID-19 vaccine update 9 the community 20 Connecting with Roma’s farming community 12 Collaborating to help prevent domestic violence 21 School holiday colour splash in Charleville 13 Driving Miss Daisy on World Health Day 13 Our Resources 22 Vintage cars come to Charleville 14 Reconnect with Village Connect 22 Disney Princesses tour Cunnamulla 15 South West Spirit Award – Chrissy Tincknell 24 Introducing Tallis Landers – Roma CAN’s new chair 16 On the road with the Oral Health Team 17 Ryan’s Rule 18 Cover image: South West HHS Executive Director Allied Health Helen Wassman catches up with Bollon CAN member Larry Wilson PULSE April 2021 edition | South West Hospital and Health Service 1 We respectfully acknowledge the traditional owners of the lands across the South West. We also pay our respects to the current and future Elders, for they will inherit the responsibility of keeping Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture alive, and for creating a better life for the generations to follow. We believe the future happiness and wellbeing of all Australians and our future generations will be enhanced by valuing and taking pride in Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples – the oldest living culture of humanity. -

11 Council Meeting 17 September 2020

17 SEPTEMBER 2020 New Footpath Victoria Street Morven MURWEH SHIRE COUNCIL MEETING To be held Thursday 17 September 2020 Commencing at 9:00am 1. Opening Prayer 2. Apologies 3. Confirmation of minutes ; Ordinary Meeting 20 August 2020 4. Business arising from minutes 5. Correspondence for members’ information 6. Councillors to advise on any declaration of personal interest relating to agenda items. 7. Councillors to advise of any update or changes to their Register of Interests 8. Chief Executive Officers Reports; i. Finance ii. HR iii. WH&S iv. Tourism v. Library vi. Environment and Health vii. Engineering 9. Correspondence for consideration 10. Closure FINANCIAL REPORT COUNCIL MEETING 17th September 2020 Mayor and Councillors Murweh Shire Council CHARLEVILLE QLD 4470 Highlights of this month’s Financial Report: Report - Period Ending 31 August 2020. Revenue Total revenue of $7.760M to 31 August 2020 represents 23% of the total budget of $33.273M. These statements are for 2 months of the financial year and generally would represent 17% of the overall budget. Rates are to go out on 11 September with a discount period until 31 December, 2020. Generally budgets are on target for the 2nd month of the financial year. Expenses Total expenditure of $2.658M to 31 August 2020 represents 11% of the total budgeted expenditure of $23.309M. Outcome There is currently a cash surplus of $5.102M. Capital Works See the Capital Funding Report 2020 – 21 for details of all projects. 1. Cash Position 2. Monthly Cash Flow Estimate 3. Comparative Data 4. Capital Funding – budget V’s actual 5. -

South West District

142°0'E CENTRAL WESTERN DISTRICT 144°0'E # 146°0'E 148°0'E # FITZROY DISTRICT 150°0'E 7 ! ! 1 d E 4 ! oa 6 B 6 R 4 t " D 2 C 5 Banana 5 e B Birkhead 87A A Bauhinia d m AR D O Em COO EV R " 8 ! Thangool R # North CUNNAMULLA CENTRAL HIGHLANDS B 13A LANDSBOROUGH HIGHWAY 36B BALONNE HIGHWAY DIAMANTINA St 3 Moura DAWSON - R # 0 4 # 959 R 776 ll 1 O 6C CENTRAL # ka 1 3 REGIONAL COUNCIL 637 # (Morven - Augathella) (Bollon - Cunnamulla) W E Ra c C SHIRE COUNCIL ilw a W # ay S Bl 7 R " # a V t 4 I ! IV 1 ll E N Cungelella 225 638 N 1196 13B LANDSBOROUGH HIGHWAY! Y 37A CASTLEREAGH HIGHWAY D a # C # R k 223 n R 642 # m A O ! A o ! PAROO e l A l F 7 S Kianga lo Emmet (Augathellae - Tambo) (Noondoo - Hebel) t re W o nc 771 R r t 8 WOORABINDA S t e # A B S W S t SHIRE COUNCIL H S C N ! 6 d Moonford t A 18D WARREGO HIGHWAY 2 79A COOPER DEVELOPMENTAL ROAD M a G - n ab LONGREACH A 8 " BALONNE el S 553 D ABORIGINAL I ! a o 5 t e l v S m 253 I e t R A l t R D H ek n a S n Cre e i (Miles - Roma) (Quilpie - Bundeena) a B BLACKALL-TAMBO S l 1018 REGIONAL V Coominglah J E l " o A h SHIRE COUNCIL # m i y # SHIRE COUNCIL n m 3 t e a ! r l c ! W t 601 O a t 94 ! s s 2 i A # W a Y ! ## # Ca t 18E WARREGO HIGHWAY 86A SURAT DEVELOPMENTAL ROAD W REGIONAL COUNCIL w Lo S H B ! COUNCIL N d S t M M u 271 975 i e 203 s t 6 e S 1 R n O 112 t 3 k u S e o d 3 E R Cre R S St 208 Ta m b o # (Roma - Mitchell)N (Surat - Tara) t L R C MITCHEL 241 B IV 1016 3 k n 9 # R # 6B S 4A C h 36 d A R n 639 18F WARREGO HIGHWAY 93A DIAMANTINA DEVELOPMENTAL ROAD A 2 a Carnarvon o lic 3A e -

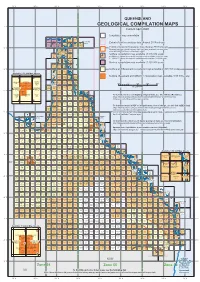

Qld-Geological-Compilation-Maps-Index.Pdf

138° E 140° E 142° E 144° E 146° E 148° E 150° E 152° E 154° E QUEENSLAND GEOLOGICALCOMPILATIONMAPS 8° S I 8° S Current April' 2020 Compilationmapu navailabl e BENS MARI BOIGU SAIBAI DARU BRAMBLE BACH 7279 7379 7479 7579 CAY □ 7179 7679 BOIGU DARU MAER ISLAND SC54-7 SC54-8 SC55-5 Extento f s u rfacegeologydata(Augus t 2018release) TURUCAY DELIVERANCE MABUIAG GABBA RENNEL DARNLEY MURRAY 7178 ISLAND ISLAND ISLAND ISLAND ISLAND ISLANDS 7278 7378 7478 7578 7678 7778 10° S Extento f basementgeologydata(Augus t 2018release) 10° S MOA SASSIE COCONUT Basementgeologycompilationmaps haveonlybeengeneratedov ermaps hee t ISLAND ISLAND ISLAND 7377 7477 7577 areasw ithsignficantbasementgeologyconteni t TORRES STRAIT SC54-12 M M BOOBY ARTUB THURSDAY CAPE Surfacecompilationmapavailable(1:100000s cale) ISLAND ISLAND ISLAND YORK 7276 7576 7376 7476 M — MINOCC(MineralOc cu r rence)compilationmapavailable(1:100000scale) M — MINOCC(MineralOc cu r rence)compilationmapavailable(1:50000s cale) VRI LYA ORFORD BOYDONG POINT BAY ISLAND 7375 7475 7575 JARDINE RIVER ORFORD BAY Surfacecompilationmapavailable(1:250000s cale ) SC54-15 SC54-16 SKARDON SHELBURNE CAPE MAPOON RIVER BAY GRENVILLE 7274 7374 7474 7574 12° S PENNE- SurfaceandBasementcompilationmapavailable(1:100000s cale ) 12° S FATHER TEMPLE RIVER AGNEW MORETON BAY 7273 7373 7473 7573 Available1:50000MapSheet s WEI PA CAPE WEYMOUTH SD54-3 YORK BATAVI A SD54-4 CAPE CAPE WEI PA DOWNS DOWNS DIRECTI ON Surface,BasementandMINOCCcompilationmapavailable(1:50000scale ) WEYMOUTH 7272 7372 7472 7672 M M 7572 M M M M -

Council Meeting

14 June 2018 COUNCIL MEETING Installation of new footpath at Graham Andrew’s Park. MURWEH SHIRE COUNCIL MEETING TO BE HELD ON THURSDAY 14 JUNE 2018 1. Opening Prayer 2. Apologies 3. Confirmation of minutes – Ordinary Meeting 10 May 2018 4. Business arising from minutes 5. Correspondence for members’ information 6. Chief Executive Officers Reports; i. Finance ii. HR/WH&S iii. Tourism iv. Stock Routes v. Environment and Health vi. Engineering 7. Correspondence for consideration 8. Closure ITEMS FOR CONSIDERATION 2018/2019 BUDGET Date Project Estimate Grant Council Proposed $ s Budget $ $ Nov 06 New Shed/Office – Morven Works Depot 80,000 - 80,000 CEO Mar 08 Extend powerline to Archery Club 117,000 117,000 CEO Jan 09 Charleville Depot and Store 1,000,000 1,000,000 CEO Oct 12 Connect Mains Power Charleville Polocrosse 74,000 74,000 CEO Paint and Refurbish Internal of Council Office Oct 13 60,000 60,000 CEO and Chambers Oct 13 Develop Aurora Stage III Residential Blocks 2,500,000 2,500,000 CEO Oct 13 Columbarium at Augathella Cemetery 20,000 20,000 Council Aug 15 Charleville Water Play Park Cr Liston Dec 15 Face lift to Council Administration buildings Cr Eckel Murweh Shire Council Monthly Financial Report Meeting 14 June 2018 Mayor and Councillors Murweh Shire Council CHARLEVILLE QLD 4470 Councillors, Highlights of this month’s Financial Report include: Revenue Total revenue of $19.338M to 31 May 2018 represents 70% of the total budget of $27.6M. These statements are for the eleventh month of the financial year and generally would represent 91% of the overall budget.