The Geometry of Songwriting : the 4 Dimensions of a Song and the Importance of Time. by Bill Pere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steppenwolf Live Mp3, Flac, Wma

Steppenwolf Live mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Live Country: Canada Style: Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1976 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1286 mb WMA version RAR size: 1603 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 442 Other Formats: RA MMF AUD MP1 FLAC VOC AU Tracklist A1 Sookie, Sookie 3:09 A2 Don't Step On The Grass, Sam 6:01 A3 Tighten Up Your Wig 4:23 B1 Monster 10:00 B2 Draft Resister 4:00 B3 Power Play 5:35 C1 Corina, Corina 3:47 C2 Twisted 5:01 C3 From Here To There Eventually 6:52 D1 Hey Lawdy Mama 2:57 D2 Magic Carpet Ride 4:13 D3 The Pusher 6:01 D4 Born To Be Wild 5:51 Credits Engineer – Ray Thompson Performer – Goldy McJohn, Jerry Edmonton, John Kay, Larry Byron*, Nick St. Nicholas Photography By, Design – Tom Gundelfinger Producer – Gabriel Mekler Notes Recorded live at various concerts during early 1970. Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Runout Side A): 62 ABC 464 - 1L 28 6 78 J-24022 - A Matrix / Runout (Runout Side B): 62 ABC 464 - 2L 28 6 78 J-24022 - B Matrix / Runout (Runout Side C): 62 ABC 464 - 3L 29 6 78 J-24022 - 3 Matrix / Runout (Runout Side D): 62 ABC 464 - 4L 29 6 78 4 Rights Society: S.I.A.E. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Live (2xLP, DSD 50075 Steppenwolf Dunhill DSD 50075 US 1970 Album) ABC/Dunhill DSD50075 Steppenwolf Live (2xLP) DSD50075 US Unknown Records Live Vol.1 (LP, DS-50075-1 Steppenwolf Probe DS-50075-1 Venezuela 1970 Album) Live (LP, 1J 062-91.206 Steppenwolf Stateside 1J 062-91.206 Spain 1970 Album) Live (2xLP, 250 424-1 250 424-1 Steppenwolf Album, RE, MCA Records Germany Unknown (MCA 2-6013) (MCA 2-6013) Gat) Related Music albums to Live by Steppenwolf Steppenwolf - 16 Original World Hits Steppenwolf - Early Steppenwolf Steppenwolf - Magic Carpet Ride / Sookie, Sookie Steppenwolf - The Greatest Hits - Born To Be Wild Steppenwolf - Steppenwolf Live Steppenwolf - Monster Steppenwolf - 16 Greatest Hits Steppenwolf - Magic Carpet Ride Steppenwolf - Born To Be Wild / Magic Carpet Ride Steppenwolf - Steppenwolf. -

Scotland's Economic Future

SCOTLAND’S ECONOMIC FUTURE EDITED BY PROFESSOR SIR DONALD MACKAY 2011 First published October 2011 © Reform Scotland 2011 7-9 North St David Street, Edinburgh, EH2 1AW All rights reserved SCOTLAND’S ECONOMIC FUTURE EDITED BY PROFESSOR SIR DONALD MACKAY Published by Reform Scotland Reform Scotland is an independent, non-party think tank that aims to set out a better way to deliver increased economic prosperity and more effective public services based on the traditional Scottish principles of limited government, diversity and personal responsibility. The views expressed in this publication are those of the contributors and not those of Reform Scotland, its managing Trustees, Advisory Board or staff. October 2011 Reform Scotland is a charity registered in Scotland (No SCO39624) and is also a company limited by guarantee (No SC336414) with its Registered Office at 7-9 North St David Street, Edinburgh, EH2 1AW. Cover design and typesetting by Cake Graphic & Digital Printed in Scotland by Allander CONTENTS BIOGRAPHIES V PREFACE by PROFESSOR SIR DONALD MACKay IX CHAPTER 1 by PROFESSOR SIR DONALD MACKay 1 The framework, the authors and Home Rule. CHAPTER 2 by PROFESSOR JOHN Kay 11 Is recent economic history a help? CHAPTER 3 by PROFESSOR DAVID SIMPSON 23 An environment for economic growth: is small still beautiful? CHAPTER 4 by JIM & MARGARET CUTHBERT 35 GERS: where now? CHAPTER 5 by PROFESSOR DREW Scott 45 The Scotland Bill: way forward or cul de sac? CHAPTER 6 by PROFESSOR DAVID BELL 65 The Scottish economy: seeking an advantage? CHAPTER 7 by -

{Download PDF} Steppenwolf Ebook, Epub

STEPPENWOLF PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Hermann Hesse,David Horrocks | 272 pages | 05 Apr 2012 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141192093 | English | London, United Kingdom Steppenwolf PDF Book Play album Buy Loading. Wikimedia Commons Wikiquote. Steppenwolf fights Wonder Woman. In October we gave our last performance. A Girl I Knew. Live In Louisville! Friday 2 October Wednesday 7 October Born to Be Wild. Wednesday 29 July Hermann Hesse. Release Date January 29, This episode confirms to Harry that he is, and will always be, a stranger to his society. Thursday 25 June Iron Butterfly. Romantic Sad Sentimental. Following Darkseid's orders, Steppenwolf invaded Earth about 5 thousand years before the Battle of Metropolis with and his vast army of Parademons and attempted to conquer the planet but were forced into their first retreat ever by the combined armies of the Humans , Amazons , Atlanteans , and the Olympian Gods , losing 3 Mother Boxes with him. The quality of the acting is also difficult to gauge because the interactions between characters are already supposed to be so far removed from the kinds of things that people in your life most likely say and do. Add image 10 more photos. Cancel Save. The… read more. Now with the 3 Mother Boxes on his power, Steppenwolf decided that it was time to seal the Earth's fate via destroying it as he did in the past with several other planets under the orders of Darkseid's Elite. Darkseid with Steppenwolf at his side led his forces to Earth in search of the Anti Life Equation , where he met resistance from an alliance of Old Gods , Humans , Amazons , Atlanteans and Lanterns , who stopped him from uniting the three Mother Boxes and turning the planet into a copy of Apokolips. -

Love Lives on – Lyrics Celebrate the Night

LOVE LIVES ON ʹ LYRICS CELEBRATE THE NIGHT Gregg Karukas/Ron Boustead Arranged by Gregg Karukas Come and see the sky turn to red and gold Come and hear the sounds of the night unfold &ŽƌƚŚĞƌĞ͛ƐĂǁĂƌŵǁŝŶĚƵƉŽŶƚŚĞĂŝƌ And the moon is beyond compare Shining above This night was made for love Oh come, come share this magic time For this moment is yours and mine And life goes too fast /ƚ͛ƐƵƉƚŽƵƐƚŽŵĂŬĞŝƚůĂƐƚ Chorus: Come celebrate the night Festejar na noite Come dance with me tonight Festejar na noite Here, darling here where the music plays Let the sound take your heart away Give in to the groove /ƚ͛ƐƚŝŵĞĨŽƌƵƐƚŽŵĂŬĞŽƵƌŵŽǀĞ Chorus: Come celebrate the night Festejar na noite Come dance with me tonight Festejar na noite And we can look at the world The stars are revealing A different view A whole other feeling And when the rhythm starts You move closer to me We seize the night We turn up the music and dance Teo Lima ʹ Drums, Percussion John Pena ʹ Bass Marty Ashby ʹ Acoustic Guitar Pat Kelly ʹ Electric Guitar Frank Zotoli ʹ Keyboards Patrice Rushen ʹ Acoustic Piano Solo Luis Conte ʹ Percussion Jay Ashby ʹ Percussion, Trombone Ron King ʹ Trumpet Dick Mitchell ʹ Saxophones Renata Lima ʹ Background Vocals Kenia ʹ Lead Vocals Karukas Music / Art-Rock Music LOVE LIVES ON Gregg Karukas/Jenny Yates Arranged by Gregg Karukas It was his decision To walk away zŽƵ͛ƌĞůĞĨƚďĞůŝĞǀŝŶŐ ,Ğ͛ůůĐŽŵĞďĂĐŬƐŽŵĞĚĂLJ;ƚŚĞůŽǀĞůŝǀĞƐŽŶͿ Every fantasy Finally had a chance The best of your dreams In a fleeting dance zŽƵŬŶŽǁŝƚ͛ƐŶŽƚƌŝŐŚƚ To still want him every night The love lives -

John Kay & Steppenwolf

JOHN KAY & STEPPENWOLF Biography CELEBRATE THEIR 50TH ANNIVERSARY "The central theme of Feed The Fire," says John Kay, "is, 'don't let the bastards get you down!'" Lyrically, songs such as "Rock & Roll Rebels" and "Hold On" focus on the resiliency of the human spirit in spite of life's many setbacks. The title song speaks to the needs of the inner flame that burns in all of us and drives us in our quest for fulfillment. Other tracks, such as "Man On A Mission", "Rock Steady" and "Rage", are songs of defiance and passion, while "Bad Attitude" and "Give Me News I Can Use", rely on tongue-in-cheek and at times sardonic humor to make their point. In Kay's words: "This album is about and for all the rock and roll rebels, be they 14 or 54, who refuse to throw in the towel and who struggle to keep their dreams alive in the face of ever diminishing freedom." With "Feed The Fire," their most potent album in years, Kay and company have written the newest chapter of the Steppenwolf legend. Kay has certainly lived the life of a rock and roll rebel himself. After a perilous midnight escape from post-war East Germany as a child, he grew up with a steady diet of Armed Forces Radio and became inspired by the likes of Little Richard and Chuck Berry. At age 13, John decided to make rock and roll his life. "Considering I was only 13, legally blind, spoke the wrong language and was on the wrong side of the ocean, maybe I was a little optimistic," he says. -

Jukebox Decades – 100 Hits Ultimate Soul

JUKEBOX DECADES – 100 HITS ULTIMATE SOUL Disc One - Title Artist Disc Two - Title Artist 01 Ain’t No Sunshine Bill Withers 01 Be My Baby The Ronettes 02 How ‘Bout Us Champaign 02 Captain Of Your Ship Reparata 03 Sexual Healing Marvin Gaye 03 Band Of Gold Freda Payne 04 Me & Mrs. Jones Billy Paul 04 Midnight Train To Georgia Gladys Knight 05 If You Don’t Know Me Harold Melvin 05 Piece of My Heart Erma Franklin 06 Turn Off The Lights Teddy Pendergrass 06 Woman In Love The Three Degrees 07 A Little Bit Of Something Little Richard 07 I Need Your Love So Desperately Peaches 08 Tears On My Pillow Johnny Nash 08 I’ll Never Love This Way Again D Warwick 09 Cause You’re Mine Vibrations 09 Do What You Gotta Do Nina Simone 10 So Amazing Luther Vandross 10 Mockingbird Aretha Franklin 11 You’re More Than A Number The Drifters 11 That’s What Friends Are For D Williams 12 Hold Back The Night The Tramps 12 All My Lovin’ Cheryl Lynn 13 Let Love Come Between Us James 13 From His Woman To You Barbara Mason 14 After The Love Has Gone Earth Wind & Fire 14 Personally Jackie Moore 15 Mind Blowing Decisions Heatwave 15 Every Night Phoebe Snow 16 Brandy The O’ Jays 16 Saturday Love Cherrelle 17 Just Be Good To Me The S.O.S Band 17 I Need You Pointer Sisters 18 Ready Or Not Here I The Delfonics 18 Are You Lonely For Me Freddie Scott 19 Home Is Where The Heart Is B Womack 19 People The Tymes 20 Birth The Peddlers 20 Don’t Walk Away General Johnson Disc Three - Title Artist Disc Four - Title Artist 01 Till Tomorrow Marvin Gaye 01 Lean On Me Bill Withers 02 Here -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Trustees Comply with Sunshine Legislation SA Meeting

Trustees comply with sunshine legislation by JeE llw Meyers Sharp before s meeting convenes; and noti that all areas within the university fication to media who have requested comply with the law.” Sunshine legislation, approved it. The exact ramifications of the law during the last Indiana General on the board will not be known until Assembly session, may have an effect Two committee meetings of the after the board’s retreat August 7. on the I.U. Board o# Trustee meetings, board are already open - student Gonso believes sunshine legislation According to Harry Gonso, trustee affairs and faculty relations. Not open may “inhibit discussion and lengthen responsible for seeing the university to the public are committee meetings some meetings but the exact process complies with sunshine legislation. which deal with personnel, reel estate is expected to be ironed out during the Scheduled to become law and legal, fiscal and construction retreat. " September 1, sunshine legislation matters Executive sessions are also The September board meeting will requires public meetings to be open, closed to the public be the First meeting to comply with except in exempted areas such as per “The board will adopt whatever the new law According to Gonso. I U sonnel matters, real estate and litiga means possible to comply with the President John W. Ryan has asked the tion; requires the posting of sn law,” said Gonso, “as well as ask the board to comply not only with the RJverhease Apartment* agenda at the public office 48 hours university’s legal department to see letter, but the spirit of the law NY firm purchases Riverhouse Apts. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

Watkins Mind Body Spirit

ISSUE 39 / AUTUMN 2014 WWW.WATKINSBOOKS.COM WATKINS WATKINS Interview with Esoteric Temple in the heart MIND BODY SPIRIT ALICE WALKER of MIND The Cushion in London BODY the Road SPIRIT ERVIN LASZLO # 39 | # 39 Consciousness AUTUMN 2014 AUTUMN KEY in the Cosmos LESSONS 7 THE INNER LIGHT: TO Self-Realization via SPIRITUAL the Western Esoteric Tradition INTELLIGENCE by P.T. Mistleberger WATKINS BOOKS by Sarah Alexander SUPPORT INDEPENDENT BOOKSELLERS! SEVEN THOUSAND SHIVA REA Global Spiritual Map Watkins Blog WAYS TO LISTEN watkinsbooks.com/ushahidi watkinsbooks.com/review Tending the Heart Fire: Staying Close to Ley-line nodes, spiritual beauty & Book recommendations, events at Living in Flow with places of worship, ghosts, visions, Watkins, guest-posts by authors in the What is Sacred UFO sightings...Also via our app. Mind, Body & Spirit the Pulse of Life by Mark Nepo Watkins eBook App Online Bookshop iPhone, iPad & Android www.watkinsbooks.com Our new app features a unique Selected titles, including signed copies, selection of new and classic esoteric latest books and special offers. THE TRAUMA OF THE SUFI PATH OF ebooks. Download it for FREE! FREE UK shipping on orders over £30. EVERYDAY LIFE ANNIHILATION by Dr Mark Epstein by Nevit O. Ergin Shop online www.watkinsbooks.com by WATKINS BOOKS WATKINS 39 THE MEETING OF PAUL BRUNTON AND RAMANA MAHARSHI 19-21 Cecil Court, WC2N 4EZ :: Leicester Sq tube THE MINOANS . ALEISTER CROWLEY . THE MOUNT ATHOS DIET BEST VERSION OF YOURSELF AT EVERY AGE . QIGONG SECRETS OPEN EVERY DAY! 1893 WATKINS 9772055280003 PSYCHIC DEVELOPMENT . THE DIVINE MESSAGES AROUND US ISSUE 39, £4.95 39, ISSUE CONTEMPORARY SPIRITUALITY . -

WAVEY DAVEY B's KARAOKE LISTING SONG ARTIST 1234

WAVEY DAVEY B's KARAOKE LISTING SONG ARTIST 1234 Sumptin' New Coolio 16th Avenue Lacy J Dalton 1999 Prince 2 4 6 8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 2 Pints Of Lager And A Packet Of Cr Splodgenessabounds 20th Century Boy T Rex 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 24 Hours From You Next Of Kin 48 Crash Suzi Quatro 5 4 3 2 1 Manfred Mann 5 6 7 8 Steps 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Simon And Garfunkel 74 75 Connells 867 5309 Jenny Tommy Tutone 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 99 Red Balloons Nena Abilene George Hamilton Iv Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Act Like You Know Fat Larry's Band Act Naturally Buck Owens Addams Groove M C Hammer Addicted To Love Robert Palmer Adios Amigo Jim Reeves Africa Toto After The Loving Engelbert Humperdinck Agadoo Black Lace Against All Odds Phil Collins Against The Wind Bob Seger Aida Sarah Mclachlan Ain't Goin' Down Till The Sun Comes Garth Brooks Ain't Gonna Bump No More Joe Tex Ain't Had No Lovin' Connie Smith Ain't Misbehavin' Tommy Bruce Ain't No Mountain High Enough Diana Ross Ain't No Stoppin' Us Now Mcfadden And Whitehead Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers Ain't No Woman Four Tops Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan Ain't Nothing But A House Party Showstoppers Ain't Talkin' 'bout Love Van Halen Ain't That A Shame Fats Domino Ain't That Just The Way Lutricia Mcneal Ain't Too Proud To Beg Temptations Air That I Breathe Hollies Airport Motors Alfie Cilla Black Alison My Aim Is True Elvis Costello Alive And Kicking Simple Minds All About The Money Meja All Around My Hat Steeleye Span All Around The World Lisa Stansfield All Day And All -

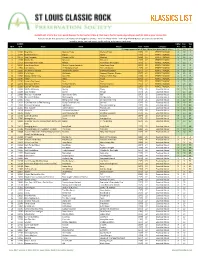

KLASSICS LIST Criteria

KLASSICS LIST criteria: 8 or more points (two per fan list, two for U-Man A-Z list, two to five for Top 95, depending on quartile); 1984 or prior release date Sources: ten fan lists (online and otherwise; see last page for details) + 2011-12 U-Man A-Z list + 2014 Top 95 KSHE Klassics (as voted on by listeners) sorted by points, Fan Lists count, Top 95 ranking, artist name, track name SLCRPS UMan Fan Top ID # ID # Track Artist Album Year Points Category A-Z Lists 95 35 songs appeared on all lists, these have green count info >> X 10 n 1 12404 Blue Mist Mama's Pride Mama's Pride 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 1 2 12299 Dead And Gone Gypsy Gypsy 1970 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 2 3 11672 Two Hangmen Mason Proffit Wanted 1969 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 5 4 11578 Movin' On Missouri Missouri 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 6 5 11717 Remember the Future Nektar Remember the Future 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 7 6 10024 Lake Shore Drive Aliotta Haynes Jeremiah Lake Shore Drive 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 9 7 11654 Last Illusion J.F. Murphy & Salt The Last Illusion 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 12 8 13195 The Martian Boogie Brownsville Station Brownsville Station 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 13 9 13202 Fly At Night Chilliwack Dreams, Dreams, Dreams 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 14 10 11696 Mama Let Him Play Doucette Mama Let Him Play 1978 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 15 11 11547 Tower Angel Angel 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 19 12 11730 From A Dry Camel Dust Dust 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 20 13 12131 Rosewood Bitters Michael Stanley Michael Stanley 1972 27 PERFECT