Toward a De-Colonial Performatics of the US Latina and Latino Borderlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case 7:17-Cv-06513-CS Document 118 Filed 03/06/18 Page 1 of 33

Case 7:17-cv-06513-CS Document 118 Filed 03/06/18 Page 1 of 33 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ----------------------------------------------------------------------x CAN’T STOP PRODUCTIONS, INC., MEMORANDUM DECISION Plaintiff, AND ORDER - against - No. 17-CV-6513 (CS) SIXUVUS, LTD., ERIC ANZALONE, ALEXANDER BRILEY, FELIPE ROSE, JAMES F. NEWMAN, RAYMOND SIMPSON, and WILLIAM WHITEFIELD, Defendants. ----------------------------------------------------------------------x Appearances: Stewart L. Levy, Esq. Eisenberg Tanchum & Levy White Plains, New York Robert S. Besser, Esq. Law Offices of Robert S. Besser Pacific Palisades, California Counsel for Plaintiff Karen Willis d/b/a Harlem West Entertainment San Diego, California Plaintiff-Intervenor Pro Se Sarah M. Matz, Esq. Gary Adelman, Esq. Adelman Matz P.C. New York, New York Counsel for Defendants Seibel, J. This case involves a dispute over the “Village People” trademarks associated with the disco group that had several hits – including “Macho Man,” “In the Navy,” and most famously “YMCA” – in the late 1970s. On February 16, 2018, the Court issued an Order, with opinion to follow, that denied Defendant’s motion for a preliminary injunction and vacated the amended 1 Case 7:17-cv-06513-CS Document 118 Filed 03/06/18 Page 2 of 33 temporary restraining order (“TRO”) that was in place. (Doc. 115.) This Memorandum explains the reasons for the Court’s decision. I. PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND Plaintiff Can’t Stop Productions, Inc. filed this lawsuit against Defendants Sixuvus Ltd. and its members Eric Anzalone, Alexander Briley, Felipe Rose, James F. Newman, Raymond Simpson, and William Whitefield on August 25, 2017, for trademark infringement and a declaratory judgment that Plaintiff is the owner of all rights, title and interest in the “Village People” trademarks. -

America Embraces Jayms Blonde

America Embraces Jayms Blonde MIAMI HERALD: A hairdresser by trade and a secret agent by choice, Jayms Blonde and his faithful pedicurist Precious Needmoore, lead the fight to save the planet from bad hair and bad air. Armed with bulletproof-mousse, Uzi blow-dry- ers, and hair-curler-hand-grenades, they rescue the dude-in-distress, and make saving the earth look fabulous. CONETICUTT POST: The combination of wild, globetrotting adventure and stylish graphic novel illustrations every few pages gives the book a wonderful over-the-top feel. Blonde’s foes are evil capitalists whose industries spike global warming and other eco-disasters. The hero and his cohorts work for STOP (Stop Terrorizing Our Planet) which is covertly funded by media celebrities. James Bond fought an organization known as SPECTRE (Special Executive for Counter-Intelligence, Terrorism, Revenge and Extortion) led by the supremely evil Ernst Blofeld. Blonde and STOP’s primary foe is ZENRON (Zillionaire Environmental Nihilist Reinstating Oligarchy Nobility). The group is repre- sented in the first adventure by “the richest, most beautiful and most heartless woman in the universe: Zaroya Sylva Kenmore Cohen Abud Grimaldi Chang.” Cabell clearly had a ball transforming literature and film’s most promiscuous het- erosexual spy into his very active gay hero. KIRKUS DISCOVERIES: Cabell makes the over-the-top zaniness and mock action-hero antics fun, and everything congeals into a wildly enjoyable ride for readers who enjoy the adventures of a muscle-bound, crime-fighting queen in tights. A super-silly, whirling first episode that will leave gay superhero fans scratching their heads-and eager for the next installment. -

Dwight Clark Touchdown in the 1982 NFC Championship, Sending the 49Ers to the Super Bowl? ANSWER: the Catch

Delaware Winter Invitational, 2010 Old School themed trash packet by Mark Pellegrini, Mike Marra-Powers, and others Tossups 1) An elevator music version of this song was used in the mall scene in Minority Report. This song, which won the 1962 Grammy for Record of the Year, re-launched lyricist Johnny Mercer's career. It has since become a staple song for Andy Williams. The singer tells about two drifters who set off to see the world, crossing the titular object, which is wider than a mile. Originally sung by Audrey Hepburn for Breakfast at Tiffany's, this is for ten points what Henry Mancini song? ANSWER: "Moon River" 2) One play of this name occurred in the 1976 Grey Cup, when Ottawa tight end Tony Gabriel faked a post pattern and scored the game-winning touchdown in the corner. Another play with this name occurred in the 2001 Michigan-Michigan State game, when MSU quarterback Jeff Smoker threw the game-winning touchdown to T.J. Duckett with one second left. A more well-known play with this name occurred in the 1954 World Series, when Vic Wertz’s liner to deep center was caught by Willie Mays. These plays all share what name, which for ten points usually refers to the Joe Montana to Dwight Clark touchdown in the 1982 NFC Championship, sending the 49ers to the Super Bowl? ANSWER: The Catch 3) This film marked the major motion picture debut of Christopher Lloyd as Taber. The role of the central villain in this movie was turned down by six actresses before largely- unknown Louise Fletcher agreed to play it. -

Village People Macho Man Mp3, Flac, Wma

Village People Macho Man mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop Album: Macho Man Country: Japan Released: 1978 MP3 version RAR size: 1258 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1453 mb WMA version RAR size: 1142 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 488 Other Formats: MMF ADX FLAC TTA WAV MIDI VOX Tracklist A1 Macho Man 5:18 A2 I Am What I Am 5:37 B1 Key West 5:42 Medley 4:36 B2a Just A Gigolo 1:15 B2b I Ain't Got Nobody 3:21 B3 Sodom And Gomorrah 6:17 Companies, etc. Distributed By – Casablanca Record And FilmWorks, Inc. Manufactured By – Casablanca Record And FilmWorks, Inc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Casablanca Record And FilmWorks, Inc. Copyright (c) – Casablanca Record And FilmWorks, Inc. Credits Arranged By [Rhythm & Percussion] – Jacques Morali Arranged By [Strings & Horns], Conductor – Horace Ott Arranged By [Vocals] – Jacques Morali, Victor Willis Backing Vocals – Alexander Briley, David Hodo, Felipe Rose, Glenn Hughes , Randy Jones Bass – Alfonso Carey Congas – E. (Crusher) Bennett* Drums – Russell Dabney Electric Piano [Fender Rhodes], Clavinet – Nathanial "Crocket" Wilke* Engineer – Gerald Block Lead Guitar – Jimmy Lee Lead Vocals – Victor Willis Other [Make Up] – Pascale Percussion – Peter Whitehead, Phil Kraus Percussion [Foot Bells] – Felipe Rose Photography By – J. Galluzzi* Producer – Jacques Morali Rhythm Guitar – Rodger Lee Written-By – Henri Belolo (tracks: A1 to B1, B3), Irving Caesar (tracks: B2a), Jacques Morali (tracks: A1 to B1, B3), Leonello Casucci (tracks: B2a), Peter Whitehead (tracks: A1 to B1, B3), Roger Graham (tracks: B2b), Spencer Williams (tracks: B2b), Victor Willis (tracks: A1 to B1, B3) Notes Produced for Can't Stop Productions, Inc. -

1 "I Will Not Be Conquered": Popular Music and Indigenous Identities In

"I Will Not Be Conquered": Popular Music and Indigenous Identities in North America Submitted by William Rees, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Masters by Research in History, January 2019. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that any material that has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University has been acknowledged. (Signature) …… ………………………………………………………………………… 1 “I Will Not Be Conquered”: Popular Music and Indigenous Identities in North America 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisors, Dr Bryony Onciul and Dr Kristofer Allerfeldt for their wisdom and advice throughout the construction of this thesis. I would also like to thank other academics who have assisted this research at University of Exeter’s Penryn campus: Dr Garry Tregidga, Dr Nicola Whyte, Dr Timothy Cooper and Dr Richard Noakes. The input of indigenous musicians has been fundamental to this project. I am indebted to the participation of Kelly Derrickson, Danielle Egnew, Apryl Allen, Keith Secola, Mitch Walking Elk, Leah Shenandoah, Joanne Shenandoah, Christian Parrish Takes the Gun, Skye Stoney, and Raye Zaragoza. Furthermore, I am appreciative for having had informative e-mail correspondences with Matilda Allerfeldt, Iea Haggman, and Professor John Troutman. Finally, I would like to thank my friends for their support: Yusef Sacoor, Em Parker, Emma Soanes, Molly Taylor, Lauren Clarke, Holly King, James Kaffenberg, Dan Baldry, Dylan Jones, and Sarah Reel. -

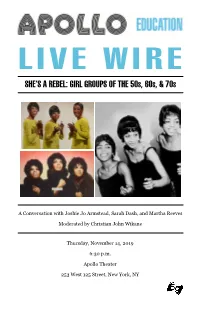

View the Live Wire Program Book

A Conversation with Joshie Jo Armstead, Sarah Dash, and Martha Reeves Moderated by Christian John Wikane Thursday, November 14, 2019 6:30 p.m. Apollo Theater 253 West 125 Street, New York, NY The Chantels “Maybe,” 1957 The Shirelles “I Met Him on a Sunday,” 1958 The Exciters “Tell Him,” 1962 The Crystals “Da Doo Ron Ron,” 1963 The Velvelettes “Needle in a Haystack,” 1964 The Supremes “Back in My Arms Again,” 1965 The Blossoms “Cry Like a Baby,” 1967 The Sweet Inspirations “Sweet Inspiration,” 1968 The Three Degrees “You’re the One,” 1970 The Pointer Sisters “Yes We Can Can,” 1973 Scan the QR code to listen to the playlist on APOLLO LIVE WIRE: SHE’S A REBEL - GIRL GROUPS Tonight, we honor the power of harmony through the stories of three phenomenal women, Martha Reeves, Sarah Dash, and Joshie Jo Armstead. As founding members of “girl groups” who formed during the 1960s, they each created a sound and style that expanded the foundation set by forebears like the Shirelles, the Chantels, and the Bobbettes. The hits are legion. The groups are legendary. Hearing each woman tell her story, it’s clear that being in a group was often a springboard to reinvention, sometimes within the group itself, other times as a solo artist, and occasionally venturing into spheres beyond music. From opening the Motown Revue as Martha & the Vandellas to presiding on Detroit’s City Council, Martha Reeves embodies fearless strength and dedication. From being christened one of the “Sweethearts of the Apollo” as a member of Patti LaBelle & the Blubelles to becoming the very first Music Ambassador for Trenton, NJ, Sarah Dash is rich in soul and spirit. -

The Village People by Robert Kellerman

The Village People by Robert Kellerman Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com The Village People were a disco-era singing group formed in the late 1970s. Although the group never identified itself as gay, its primary appeal was clearly to a gay male audience. It successfully translated the interests, coded language, and iconography of the gay male subculture into music that crossed over into mainstream pop. Because the general public was largely unaware of the meanings and suggestiveness of the lyrics and costumes associated with the group, the gay audience not only enjoyed the music on its own terms, but also relished the irony of a mainstream audience unknowingly embracing subculture values and images. The Village People were formed in 1977 by French record producer Jacques Morali, who was inspired to create the group after seeing performer Felipe Rose, dressed as a Native American, singing and dancing in the streets of Greenwich Village. Hence the group's name. Morali approached Rose about forming a group and then, with his partner Henri Belelo, auditioned other singers by advertising in trade publications for "singers with mustaches." All members of the group performed in costume to represent other masculine (and, not coincidentally, gay male fantasy) archetypes: Native American Rose, construction worker David Hodo, policeman Victor Willis, soldier Alex Briley, cowboy Randy Jones, and biker leatherman Glenn Hughes. Rose was openly gay, but the other singers never addressed their sexual orientation. Regardless, The Village People's core audience was undeniably gay men, and their most popular hits were overtly homoerotic. -

“Y.M.C.A.”--The Village People (1978) Added to the National Registry: 2019 Essay by Josiah Howard (Guest Post)*

“Y.M.C.A.”--The Village People (1978) Added to the National Registry: 2019 Essay by Josiah Howard (guest post)* Aside from their shared dream of becoming rich and famous, Village People--all six band members--really didn’t have much in common. Still, their outsize fantasy, one that they’d work tirelessly to achieve, would prove to be enough. For a time at least. Mention the Village People and you’ll probably hear a snicker or two, or get a pointed pursed lip and side-eye. If that doesn’t happen you might watch as someone throws their arms into the air and contorts them into the shape of the letters Y, M, C, and A. During the late 1970s and early '80s, Village People sold more than 100 million records, had three top ten pop hits, four top twenty dance/club hits, toured the world (selling out New York City’s 20,789-seat Madison Square Garden twice), and made a major motion picture--1980’s “Can’t Stop the Music.” They were award winners, television staples and pop culture icons whose music played everywhere: from discotheques to doctor’s offices, from underground sex clubs to bar mitzvahs, from sporting events to the local mall. And they did something more. As Casablanca Records President Neil Bogart once unequivocally observed, “It’s just Donna (Summer) and the boys (Village People): they’re the ones who keep the lights on around here.” They kept the lights on elsewhere as well. The brainchild of French/Moroccan music producers Jacques Morali and Henri Belolo--who’d previously made a name for themselves with two top twenty hits for the Ritchie Family--1975’s “Brazil” and 1976’s “The Best Disco in Town”-- Village People, it was decided, was going to do what the Ritchie Family had not managed to: ascend to the number one spot on the all-important “Billboard” pop charts. -

The Original Super Group VILLAGE PEOPLE to Perform at Marina Bay Sands for the First Time with Special Guest Appearance by BJORN AGAIN

The original super group VILLAGE PEOPLE to perform at Marina Bay Sands for the first time With special guest appearance by BJORN AGAIN Singapore, 18 January 2017 – The original 1970s disco music group, Village People, are coming to Singapore to celebrate their 40th Anniversary with a special guest appearance by Bjorn Again! Village People are one-of-a-kind and synonymous with dance music. These six talented men, featuring original founding members Felipe Rose and Alexander Briley, combine energetic choreography with outrageous fun and lots of singing and dancing, providing great entertainment for all! This special 40th anniversary tour opens at The MasterCard Theatres at Marina Bay Sands in May 2017 for 2 shows only. Tickets are now on sale. Originally formed in 1977 by French Music composer Jacques Morali, Village People quickly became an instant phenomenon throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s with chart-topping hits such as San Francisco/In Hollywood, Macho Man, Y.M.C.A, In the Navy, Go West, Can't Stop the Music and more. Their impact and influence on music have earned them the title of “Kings of Disco”, selling more than 100 million recordings worldwide and earning them a star on the coveted Hollywood Walk of Fame. The special 40th Anniversary tour will feature some of the Village People’s biggest hits as their timeless songs will once again be seen and heard. Get carried away with the most irresistible disco tunes performed in the Village People’s unique way. The members of Village People performing in Singapore include original founding members Felipe Rose and Alexander Briley , who portray the Native American and GI/Soldier respectively; Ray Simpson - the Cop who joined in 1979; Eric Anzalone - the Biker who joined in 1995, Jim Newman - the Cowboy who joined in 2013 and finally Bill Whitefield - the Construction Worker who joined full time in 2013 after having been a swing for about 10 years. -

Village People New York City Mp3, Flac, Wma

Village People New York City mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Funk / Soul / Pop Album: New York City Country: UK Released: 1985 Style: Disco, Contemporary R&B MP3 version RAR size: 1455 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1309 mb WMA version RAR size: 1122 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 286 Other Formats: ADX MP4 AU VQF XM AC3 DTS Tracklist A1 Sex Over The Phone 4:22 A2 New York City 6:00 A3 Just Give Me What I Want 6:14 A4 I Won't Take No For Answer 5:06 B1 Power Of The Night 5:58 B2 Sexual Education 5:33 B3 Sensual 4:36 B4 Sex Over The Phone (Special Remix) 4:12 Credits Arranged By – Fred Zarr Artwork – C. Caudron* Composed By – Bruce Vilanch (tracks: A1,A2,A3,A4,B1,B2,B3,B4), Fred Zarr (tracks: A1,A2,A3,A4,B1,B2,B3,B4), Jacques Morali (tracks: A1,A2,A3,A4,B1,B2,B3,B4), Ray Stephens (tracks: A3) Executive Producer – Henri Belolo Photography By – B. Leloup* Producer – Jacques Morali Notes Produced by Jacques Morali (Toutoune Productions) for Can't Stop Productions - NYC Costumes of Alex Briley, Felipe Rose and Ray Stephens courtesy of Nicolas Harle'/Paris Costumes of Jeff Olson and Glenn Hughes furnished by Nino/Paris Assistant to Jacques Morali: Frank Hudon Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year SCM 19306 Village Sex Over The Phone SCM 19306 Black Scorpio France 1985 N People (LP, Album) N Village Sex Over The Phone TC 6004 Three Eggs TC 6004 Greece 1985 People (Cass, Album) Village Sex Over The Phone TT10091 TX2 TT10091 Europe 2002 People (CD, Album, RM) Village Sex Over The Phone Can't Stop 6.11331 6.11331 Hong Kong 1985 People (LP, Album) Productions, Inc. -

The Otherings of Miss Chief: Kent Monkman's Portrait of the Artist As

The Otherings of Miss Chief: Kent Monkman’s Portrait of the Artist as Hunter By Roland Maurice B.A., B.F.A. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Carleton University OTTAWA, Ontario August 24, 2007 2007, Roland Maurice Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-36803-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-36803-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

The Long Battle for Police Torture Survivors

REPARATIONS The long battle for police torture survivors VOL 30, NO. 38 JUNE 17, 2015 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Attorney Joey Mogul at a 2011 booksigning for the book Mogul co-wrote, Queer (In)Justice. Photo by Tracy Baim BY GRETCHEN RACHEL HAMMOND At a meeting of the Chicago City Council, on May 6, Ald. Ed- ward Burke called for a vote on matters nine and 10 on the day’s agenda. Mayor Rahm Emanuel asked, “is there anyone else who would like to address this matter?” As a part of his speech, Ald. Joe Moreno asked his fellow council members to recognize some of the individuals packed into the viewing gallery above. They were given a standing ovation. Alds. Howard Brookins and Joe Moore each followed with their own declarations before Emanuel rose. “This is another step but an essential step in righting a wrong, removing a stain on the reputation of this great city and the people who make up this great city. In this action today Chicago finally will confront its past and come to terms with it and recognize when something wrong was done and be able to be strong enough to say something was wrong,” the mayor said. Many of the people Emanuel thanked for “your persistence, for never giving in or giving up and allowing the city to come face-to-face with the past” were solemnly watching. “The stain cannot be removed from the history of our city but it can be used as a lesson of what not to do and the re- sponsibility that all of us have,” Emanuel added before calling upon Burke.