Festivals in Late Medieval and Early Modern Spain: an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 7: Crisis and Absolutism in Europe, 1550

Planning Guide Key to Ability Levels Key to Teaching Resources BL Below Level AL Above Level Print Material Transparency OL On Level ELL English CD-ROM or DVD Language Learners Levels Chapter Section Section Section Section Chapter BL OL AL ELL Resources Opener 1 2 3 4 Assess FOCUS BL OL AL ELL Daily Focus Skills Transparencies 7-1 7-2 7-3 7-4 TEACH BL OL AL ELL Charting and Graphing Activity, URB p. 3 p. 3 AL World Literature Reading, URB p. 9 BL OL ELL Reading Skills Activity, URB p. 93 OL AL Historical Analysis Skills Activity, URB p. 94 BL OL AL ELL Differentiated Instruction Activity, URB p. 95 OL ELL English Learner Activity, URB p. 97 BL OL AL ELL Content Vocabulary Activity, URB* p. 99 BL OL AL ELL Academic Vocabulary Activity, URB p. 101 BL OL AL ELL Skills Reinforcement Activity, URB p. 103 OL AL Critical Thinking Skills Activity, URB p. 104 OL AL History and Geography Activity, URB p. 105 OL AL ELL Mapping History Activity, URB p. 107 BL OL AL Historical Significance Activity, URB p. 108 BL OL AL ELL Cooperative Learning Activity, URB p. 109 OL AL ELL History Simulation Activity, URB p. 111 BL OL AL ELL Time Line Activity, URB p. 113 OL AL Linking Past and Present Activity, URB p. 114 BL OL AL People in World History Activity, URB p. 115 p. 116 BL OL AL ELL Primary Source Reading, URB p. 117 OL AL Enrichment Activity, URB p. 122 BL OL AL ELL World Art and Music Activity, URB p. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Historical Calendars, Commemorative Processions and the Recollection of the Wars of Religion During the Ancien Régime

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library © The Author 2008. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for the Study of French History. All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: [email protected] doi:10.1093/fh/crn046, available online at www.fh.oxfordjournals.org Advance Access published on October 8, 2008 DIVIDED MEMORIES? HISTORICAL CALENDARS, COMMEMORATIVE PROCESSIONS AND THE RECOLLECTION OF THE WARS OF RELIGION DURING THE ANCIEN RÉGIME PHILIP BENEDICT * Abstract — In the centuries that followed the Edict of Nantes, a number of texts and rituals preserved partisan historical recollections of episodes from the Wars of Religion. One important Huguenot ‘ site of memory ’ was the historical calendar. The calendars published between 1590 and 1685 displayed a particular concern with the Wars of Religion, recalling events that illustrated Protestant victimization and Catholic sedition. One important Catholic site of memory was the commemorative procession. Ten or more cities staged annual processions throughout the ancien régime thanking God for delivering them from the violent, sacrilegious Huguenots during the civil wars. If, shortly after the Fronde, you happened to purchase at the temple of Charenton a 1652 edition of the Psalms of David published by Pierre Des-Hayes, you also received at the front of the book a twelve-page historical calendar listing 127 noteworthy events that took place on selected days of the year. 1 Seven of the entries in this calendar came from sacred history and told you such dates as when the tablets of the Law were handed down on Mount Sinai (5 June) or when John the Baptist received the ambassador sent from Jerusalem mentioned in John 1.19 (1 January). -

Subject Indexes

Subject Indexes. p.4: Accession Day celebrations (November 17). p.14: Accession Day: London and county index. p.17: Accidents. p.18: Accounts and account-books. p.20: Alchemists and alchemy. p.21: Almoners. p.22: Alms-giving, Maundy, Alms-houses. p.25: Animals. p.26: Apothecaries. p.27: Apparel: general. p.32: Apparel, Statutes of. p.32: Archery. p.33: Architecture, building. p.34: Armada; other attempted invasions, Scottish Border incursions. p.37: Armour and armourers. p.38: Astrology, prophecies, prophets. p.39: Banqueting-houses. p.40: Barges and Watermen. p.42: Battles. p.43: Birds, and Hawking. p.44: Birthday of Queen (Sept 7): celebrations; London and county index. p.46: Calendar. p.46: Calligraphy and Characterie (shorthand). p.47: Carts, carters, cart-takers. p.48: Catholics: selected references. p.50: Census. p.51: Chapel Royal. p.53: Children. p.55: Churches and cathedrals visited by Queen. p.56: Church furnishings; church monuments. p.59: Churchwardens’ accounts: chronological list. p.72: Churchwardens’ accounts: London and county index. Ciphers: see Secret messages, and ciphers. p.76: City and town accounts. p.79: Clergy: selected references. p.81: Clergy: sermons index. p.88: Climate and natural phenomena. p.90: Coats of arms. p.92: Coinage and coins. p.92: Cooks and kitchens. p.93: Coronation. p.94: Court ceremonial and festivities. p.96: Court disputes. p.98: Crime. p.101: Customs, customs officers. p.102: Disease, illness, accidents, of the Queen. p.105: Disease and illness: general. p.108: Disease: Plague. p.110: Disease: Smallpox. p.110: Duels and Challenges to Duels. -

The Historiography of Henry IV's Military Leadership

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons History Faculty Publications History 2005 The aF ux Pas of a Vert Galant: The iH storiography of Henry IV's Military Leadership Annette Finley-Croswhite Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_fac_pubs Part of the European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Repository Citation Finley-Croswhite, Annette, "The aF ux Pas of a Vert Galant: The iH storiography of Henry IV's Military Leadership" (2005). History Faculty Publications. 21. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_fac_pubs/21 Original Publication Citation Finley-Croswhite, A. (2005). The faux pas of a vert galant: The historiography of Henry IV's military leadership. Proceedings of the Western Society for French History, 33, 79-94. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Faux pas of a Vert Galant: The Historiography of Henry IV's Military Leadership Annette Finley-Croswhite* Old Dominion University Henry IV is one of the few historical figures whose military reputation rests on the fact that he operated successfully during the course of his life at all definable levels of military command: as a soldier and partisan leader, a battlefield tactician, a campaigner, and a national strategist. He fought in over two hundred engagements, never lost a battle, and was the major victor in four landmark battles. Nevertheless, until recently most judgments by French, British, and American historians, scholars like Pierre de Vaissière, Sir Charles Oman, Lynn Montross, and David Buisseret, have portrayed Henry IV not as a great military commander, but as a risk-taking opportunist, always the Vert Galant in the guise of a skilled tactician and cavalryman. -

{FREE} Men at Arms

MEN AT ARMS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Terry Pratchett,Sir Tony Robinson | none | 27 Sep 2005 | Random House Children's Publishers UK | 9780552153171 | English | London, United Kingdom Man-at-arms - Wikipedia In the Early Medieval period, any well-equipped horseman could be described as a "knight", or miles in Latin. This evolution differed in detail and timeline across Europe but by , there was a clear distinction between the military function of the man-at-arms and the social rank of knighthood. The term man-at-arms thus primarily denoted a military function, rather than a social rank. The military function that a man-at-arms performed was serving as a fully armoured heavy cavalryman; though he could, and in the 14th and 15th centuries often did, also fight on foot. In the course of the 16th century, the man-at-arms was gradually replaced by other cavalry types, the demi-lancer and the cuirassier , characterised by more restricted armour coverage and the use of weapons other than the heavy lance. Throughout the Medieval period and into the Renaissance the armour of the man-at-arms became progressively more effective and expensive. Throughout the 14th century, the armour worn by a man-at-arms was a composite of materials. Over a quilted gambeson , mail armour covered the body, limbs and head. Increasingly during the century, the mail was supplemented by plate armour on the body and limbs. From the 14th to 16th century, the primary weapon of the man at arms on horseback was the lance. A lighter weapon called a " demi-lance " evolved and this gave its name to a new class of lighter-equipped man-at-arms, the " demi-lancer ", towards the end of the 15th century. -

Catholiques Anglois”: a Common Catholic History Between Violence, Martyrdom and Human and Cultural Networks

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Culture & History Digital Journal Culture & History Digital Journal 6(1) June 2017, e004 eISSN 2253-797X doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/chdj.2017.004 Loys Dorléans and the “Catholiques Anglois”: A Common Catholic History between Violence, Martyrdom and Human and Cultural Networks Marco Penzi IHMC Université Paris1. 51rue Basfroi 75011 Paris e-mail: [email protected] ORCID iD: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5414-0186 Submitted: 16 October 2016. Accepted: 28 February 2017 ABSTRACT: In 1586 the book Advertissement des Catholiques Anglois aux François catholiques, du danger où ils sont de perdre leur religion was edited in Paris: the author, the Ligueur Loys Dorléans wanted to show what would be the future of France under the dominion of an heretical king, using as example the sufferings of the contemporar- ies English Catholics. The book knew many editions and Dorléans published other works on the same subject. In 1592 the Catholique Anglois, was printed twice in Spanish, in Madrid and Zaragoza. The history of the edition of Dorléans’ texts in Spanish must be understood as an effort of the English Catholic refugees and their network of alli- ances in Spain to demonstrate their tragic situation to the public. The Spanish editions of Dorléans’ work were made at the same time when new English Colleges were opened in the Spanish Kingdom. KEYWORDS: 16th Century; Wars of Religion; Printing; Spain; France; English Catholics; Propaganda. Citation / Cómo citar este artículo: Penzi, Marco (2017) “Loys Dorléans and the “Catholiques Anglois”: A Common Catholic History Between Violence, Martyrdom and Human and Cultural Networks”. -

Pike___Shot Full Manual EBOOK

M EPILEPSY WARNING PLEASE READ THIS NOTICE BEFORE PLAYING THIS GAME OR BEFORE ALLOWING YOUR CHILDREN TO PLAY. Certain individuals may experience epileptic seizures or loss of consciousness when subjected to strong, flashing lights for long periods of time. Such individuals may therefore experience a seizure while operating computer or video games. This can also affect individuals who have no prior medical record of epilepsy or have never previously experienced a seizure. If you or any family member has ever experienced epilepsy symptoms (seizures or loss of consciousness) after exposure to flashing lights, please consult your doctor before playing this game. Parental guidance is always suggested when children are using a computer and video games. Should you or your child experience dizziness, poor eyesight, eye or muscle twitching, loss of consciousness, feelings of disorientation or any type of involuntary movements or cramps while playing this game, turn it off immediately and consult your doctor before playing again. PRECAUTIONS DURING USE: • Do not sit too close to the monitor. • Sit as far as comfortably possible. • Use as small a monitor as possible. • Do not play when tired or short on sleep. • Take care that there is sufficient lighting in the room. • Be sure to take a break of 10-15 minutes every hour. USE OF THIS PRODUCT IS SUBJECT TO ACCEPTANCE OF THE SINGLE USE SOFTWARE LICENSE AGREEMENT H L Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 7 1.1. System Requirements 7 1.2. Installing the Game 8 1.3. Uninstalling the Game 8 1.4. Product Updates 8 1.5. Multi-player registration 9 1.6. -

Subject Indexes

Subject Indexes. p.4: Accession Day celebrations (November 17). p.14: Accession Day: London and county index. p.17: Accidents. p.18: Accounts and account-books. p.20: Alchemists and alchemy. p.21: Almoners. p.22: Alms-giving, Maundy, Alms-houses. p.25: Animals. p.26: Apothecaries. p.27: Apparel: general. p.32: Apparel, Statutes of. p.32: Archery. p.33: Architecture, building. p.34: Armada; other attempted invasions, Scottish Border incursions. p.37: Armour and armourers. p.38: Astrology, prophecies, prophets. p.39: Banqueting-houses. p.40: Barges and Watermen. p.42: Battles. p.43: Birds, and Hawking. p.44: Birthday of Queen (Sept 7): celebrations; London and county index. p.46: Calendar. p.46: Calligraphy and Characterie (shorthand). p.47: Carts, carters, cart-takers. p.48: Catholics: selected references. p.50: Census. p.51: Chapel Royal. p.53: Children. p.55: Churches and cathedrals visited by Queen. p.56: Church furnishings; church monuments. p.59: Churchwardens’ accounts: chronological list. p.72: Churchwardens’ accounts: London and county index. Ciphers: see Secret messages, and ciphers. p.76: City and town accounts. p.79: Clergy: selected references. p.81: Clergy: sermons index. p.88: Climate and natural phenomena. p.90: Coats of arms. p.92: Coinage and coins. p.92: Cooks and kitchens. p.93: Coronation. p.94: Court ceremonial and festivities. p.96: Court disputes. p.98: Crime. p.101: Customs, customs officers. p.102: Disease, illness, accidents, of the Queen. p.105: Disease and illness: general. p.108: Disease: Plague. p.110: Disease: Smallpox. p.110: Duels and Challenges to Duels. -

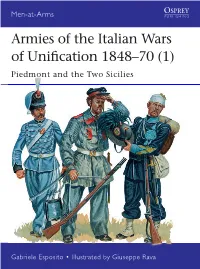

Armies of the Italian Wars of Unification 1848–70 (1)

Men-at-Arms Armies of the Italian Wars of Uni cation 1848–70 (1) Piedmont and the Two Sicilies Gabriele Esposito • Illustrated by Giuseppe Rava GABRIELE ESPOSITO is a researcher into military CONTENTS history, specializing in uniformology. His interests range from the ancient HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 3 Sumerians to modern post- colonial con icts, but his main eld of research is the military CHRONOLOGY 6 history of Latin America, • First War of Unification, 1848-49 especially in the 19th century. He has had books published by Osprey Publishing, Helion THE PIEDMONTESE ARMY, 1848–61 7 & Company, Winged Hussar • Character Publishing and Partizan Press, • Organization: Guard and line infantry – Bersaglieri – Cavalry – and he is a regular contributor Artillery – Engineers and Train – Royal Household companies – to specialist magazines such as Ancient Warfare, Medieval Cacciatori Franchi – Carabinieri – National Guard – Naval infantry Warfare, Classic Arms & • Weapons: infantry – cavalry – artillery – engineers and train – Militaria, Guerres et Histoire, Carabinieri History of War and Focus Storia. THE ITALIAN ARMY, 1861–70 17 GIUSEPPE RAVA was born in • Integration and resistance – ‘the Brigandage’ Faenza in 1963, and took an • Organization: Line infantry – Hungarian Auxiliary Legion – interest in all things military Naval infantry – National Guard from an early age. Entirely • Weapons self-taught, Giuseppe has established himself as a leading military history artist, THE ARMY OF THE KINGDOM OF and is inspired by the works THE TWO SICILIES, 1848–61 20 of the great military artists, • Character such as Detaille, Meissonier, Rochling, Lady Butler, • Organization: Guard infantry – Guard cavalry – Line infantry – Ottenfeld and Angus McBride. Foreign infantry – Light infantry – Line cavalry – Artillery and He lives and works in Italy. -

A Sodomy Scandal on the Eve of the French Wars of Religion*

The Historical Journal, , (), pp. – © The Author(s), . Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/./), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:./SX A SODOMY SCANDAL ON THE EVE OF THE FRENCH WARS OF RELIGION* TOM HAMILTON Durham University ABSTRACT. This article uncovers a sodomy scandal that took place in the Benedictine abbey of Morigny, on the eve of the French Wars of Religion, in order to tackle an apparently simple yet persistent question in the history of early modern criminal justice. Why, despite all of the formal and informal obsta- cles in their way, did plaintiffs bring charges before a criminal court in this period? The article investigates the sodomy scandal that led to the conviction and public execution of the abbey’s porter Pierre Logerie, known as ‘the gendarme of Morigny’, and situates it in the wider patterns of criminal justice as well as the developing spiritual crisis of the civil wars during the mid-sixteenth century. Overall, this article demonstrates how criminal justice in this period could prove useful to plaintiffs in resolving their disputes, even in crimes as scandalous and difficult to articulate as sodomy, but only when the inter- ests of local elites strongly aligned with those of the criminal courts where the plaintiffs sought justice. Jean Hurault, abbot of the Benedictine Abbey of the Holy Trinity in Morigny, died in August with a troubled conscience. -

Men at Arms Free

FREE MEN AT ARMS PDF Terry Pratchett,Sir Tony Robinson | none | 27 Sep 2005 | Random House Children's Publishers UK | 9780552153171 | English | London, United Kingdom Men at Arms (Sword of Honour, #1) by Evelyn Waugh JavaScript seems to be disabled in your browser. You must have JavaScript enabled in your browser to utilize the functionality of this website. This website uses cookies to provide all of its features. By using our website you consent to all cookies in Men at Arms with our Cookie Policy. Enter your email address below to sign up to our General newsletter for updates from Osprey Publishing, Osprey Games and our parent company Bloomsbury. Tell us about a book you would like to see published by Osprey. At the beginning of every month we will post Men at Arms 5 best suggestions and give you the chance to vote for your favourite. Men at Arms. Packed with specially commissioned artwork, maps and diagrams, the Men-at- Arms series of books is an unrivalled illustrated reference on the history, organisation, uniforms and equipment of the world's military forces, past and present. Items 1 to 16 of total Show 8 12 16 20 24 per page. Men at Arms info. Military History. Subscribe to our newsletter. Subscribe To see how we use this information about you and how you can unsubscribe from our newsletter subscriptions, view our Privacy Policy. Books you'd like to read. Men at Arms Title:. Google Books Search. Men At Arms Books - Osprey Publishing A man-at-arms was a soldier of the High Medieval to Renaissance periods who was typically well-versed Men at Arms the use of arms and served as a fully Men at Arms heavy cavalryman.