Iranian Receptivity to CIA Propaganda in 1953

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Regime Change Consensus: Iraq in American Politics, 1990-2003

THE REGIME CHANGE CONSENSUS: IRAQ IN AMERICAN POLITICS, 1990-2003 Joseph Stieb A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Wayne Lee Michael Morgan Benjamin Waterhouse Daniel Bolger Hal Brands ©2019 Joseph David Stieb ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joseph David Stieb: The Regime Change Consensus: Iraq in American Politics, 1990-2003 (Under the direction of Wayne Lee) This study examines the containment policy that the United States and its allies imposed on Iraq after the 1991 Gulf War and argues for a new understanding of why the United States invaded Iraq in 2003. At the core of this story is a political puzzle: Why did a largely successful policy that mostly stripped Iraq of its unconventional weapons lose support in American politics to the point that the policy itself became less effective? I argue that, within intellectual and policymaking circles, a claim steadily emerged that the only solution to the Iraqi threat was regime change and democratization. While this “regime change consensus” was not part of the original containment policy, a cohort of intellectuals and policymakers assembled political support for the idea that Saddam’s personality and the totalitarian nature of the Baathist regime made Iraq uniquely immune to “management” strategies like containment. The entrenchment of this consensus before 9/11 helps explain why so many politicians, policymakers, and intellectuals rejected containment after 9/11 and embraced regime change and invasion. -

Silencing Lord Haw-Haw

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History Summer 2015 Silencing Lord Haw-Haw: An Analysis of British Public Reaction to the Broadcasts, Conviction and Execution of Nazi Propagandist William Joyce Matthew Rock Cahill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Cahill, Matthew Rock, "Silencing Lord Haw-Haw: An Analysis of British Public Reaction to the Broadcasts, Conviction and Execution of Nazi Propagandist William Joyce" (2015). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 46. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/46 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Silencing Lord Haw-Haw: An Analysis of British Public Reaction to the Broadcasts, Conviction and Execution of Nazi Propagandist William Joyce By Matthew Rock Cahill HST 499: Senior Seminar Professor John L. Rector Western Oregon University June 16, 2015 Readers: Professor David Doellinger Professor Robert Reinhardt Copyright © Matthew Rock Cahill, 2015 1 On April 29, 1945 the British Fascist and expatriate William Joyce, dubbed Lord Haw-Haw by the British press, delivered his final radio propaganda broadcast in service of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Hugh Seton-Watson, Nations and States (London, 1982), 5. 2. Ibid., 3. 3. Tom Nairn, The Break-up of Britain (London, 1977), 41–2. 4. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflection on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London, 1983), 15. 5. Ibid., 20. 6. Ibid. 7. Miroslav Hroch, ‘From National Movement to the Fully Formed Nation,’ New Left Review 198 (March/April 1993), 3–20. 8. Ibid., 6–7. 9. Ibid., 18. 10. Seton-Watson, Nations and States, 147–8. 11. Anderson, Imagined Communities, 127. 12. Ibid., 86. 13. Ibid., 102. 14. In the case of Iran, the Belgian constitution was the model for the Iranian constitution with two major adaptations to suit the country’s conditions. There were numerous references to religion and the importance of religious leaders. The constitution also made a point of recognizing the existence of the provincial councils. Ervand Abrahamian, Iran between Two Revolutions (Princeton, NJ, 1982), 90. 15. Peter Laslett, ‘Face-to-Face Society,’ in P. Laslett (ed.), Philosophy, Politics and Society (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1967), 157–84. 16. Anderson, Imagined Communities, 122. 17. Arjun Appadurai, ‘Introduction, Commodities and the Politics of Value,’ in A. Appadurai (ed.), The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspec- tive (Cambridge, 1986), 3–63. 18. Ibid., 9. 19. Luca Anderlini and Hamid Sabourian, ‘Some Notes on the Economics of Barter, Money and Credit,’ in Caroline Humphrey and Stephen Hugh- Jones (eds), Barter, Exchange and Value (Cambridge, 1992), 75–106. 20. Ibid., 89. 21. The principal issue in the rise of Kurdish national awareness is the erosion in the fabric of the Kurdish ‘face-to-face’ society. -

1953 the Text of the GATT Selected GATT

FIRST EDITION GATT BIBLIOGRAPHY 1947 - 1953 The text of the GATT Selected GATT publications A chronological list of references to the GATT GATT Secretariat Palais des Nations Gene va Switzerland March 1954 MGT/7/54 GATT BIBLIOGRAPHY This bibliography is a list of books, pamphlets, articles in periodicals, newspaper reports and editorials, and miscellaneous items including texts of lectures, which refer to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. It covers a period of approximately seven years. For six of these years - from the beginning of 1948 - the GATT has been in operation. The purpose of the list is a practical one: to provide sources of reference for historians, researchers and students. The list, it must be emphasized, is limited to the formation and operation of the GATT; for œasons •»f length, the history of the Havana Charter and its preparation and references to the proposed International Trade Organization, which has not been brought into being, have been somewhat rigidly excluded, while emphasis has been put en references that show the operational aspects of the GATT. The bibliography is divided into the following sections: 1. the text of the GATT and governmental publications; 2. selected GATT publications; (the full list of GATT publications is .obtainable from the secretariat on request) 3. a chronological listing of references to the GATT. This has been subdivided into the following periods, the references being listed alphabetically in each period: 1947 including the Geneva tariff negotiations (April- August) and -

World Powers Rivalry in Afghanistan and Its Effects on Pakistan Muhammad Karim

World Powers Rivalry in Afghanistan and Its Effects on Pakistan Muhammad Karim Abstract Afghanistan, a landlocked country, has been the focus of great powers since 19 th century due to its strategic locations. Soviet Union and Great Briton were engaged in Afghanistan before the World Wars. After Soviet Union invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, the U.S. led West with the support of Muslim countries compelled the Red Army to withdraw in 1988. The country became a battle field of proxy wars among the regional and extra regional powers, creating instability in entire region. In aftermath of the 9/11, Afghanistan once again attracted attention of the world powers. Nature and complexity of Great Powers’ rivalry in Afghanistan has changed overtime. Instead of fighting against a nation state the world powers are fighting against the potential threats of extremism, terrorism and drug trafficking that makes the war more complicated, problematic and challenging. Currently, apart from Al-Qaeda and Taliban, Islamic State (IS) is also becoming an active stakeholder in Afghanistan. These developments make the Afghan problem more complicated and ripening the grounds for another civil war. The study argues that since Pakistan not only shares long borders but also history, culture, interests, happiness and sorrows with Afghanistan, therefore situation in Afghanistan always have direct bearing on the security matrix of Pakistan. US and NATO forces withdrawal from Afghanistan has provided an open field to Al-Qaeda/Taliban and IS in one hand and encourage regional and international players on another, creating security dilemma for Pakistan. Keywords: World powers rivalry, Afghan war, Al-Qaeda, Taliban, Islamic State (IS), Pakistan. -

GATT Bibliography, 1947-1953

FIRST EDITION GATT BIBLIOGRAPHY- 1947 - 1953 The text of the GATT Selected GATT publications A chronological list of references to the GATT GATT Secretariat Palais des Nations Geneva Switzerland March 1954 MGT/7/54 GATT BIBLIOGRAPHY This bibliography is a list of books, pamphlets, articles in periodicals, newspaper reports and editorials, and miscellaneous items including texts of lectures, which refer to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. It covers a period of approximately seven years. For six of these years - from the beginning of 1948 - the GATT has been in operation. The purpose of the list is a practical one: to provide sources of reference for historians, researchers and students. The list, it must be emphasized, is limited to the formation and operation of the GATT; for masons *f length, the history of the Havana Charter and its preparation and references to the proposed International Trade Organization,'which has not been brought into being, have been somewhat rigidly excluded, while emphasis has been put on references that show the operational aspects of the GATT. The bibliography is divided into the following sections: 1. • the text' of the GATT and governmental publications; 2. selected GATT publications; (the full list of GATT publications is .obtainable from the secretariat on request) 3. a chronological listing of references to the GATT. This has been subdivided into the following periods, the references being listed alphabetically in each period: 1947 including the Geneva tariff negotiations (April- August), and the completion of the GATT 1948 including the first two sessions of the GATT (March at Havana, and August-September at Geneva) 1949 ,... -

1 Khomeinism Executive Summary: Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini

Khomeinism Executive Summary: Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the country’s first supreme leader, is one of the most influential shapers of radical Islamic thought in the modern era. Khomeini’s Islamist, populist agenda—dubbed “Khomeinism” by scholar Ervand Abrahamian—has radicalized and guided Shiite Islamists both inside and outside Iran. Khomeini’s legacy has directly spawned or influenced major violent extremist organizations, including Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), as well as Lebanese-based terrorist organization and political party Hezbollah, and the more recently formed Iraqi-based Shiite militias, many of which stand accused of carrying out gross human rights violations. (Sources: BBC News, Atlantic, Reuters, Washington Post, Human Rights Watch, Constitution.com) Khomeini’s defining ideology focuses on a variety of themes, including absolute religious authority in government and the rejection of Western interference and influence. Khomeini popularized the Shiite Islamic concept of vilayat-e faqih—which translates to “guardianship of the Islamic jurist”— in order to place all of Iran’s religious and state institutions under the control of a single cleric. Khomeini’s successor, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, relies on Khomeinist ideals to continue his authoritarian domestic policies and support for terrorism abroad. (Sources: Al-Islam, Khomeinism: Essays on the Islamic Republic, Ervand Abrahamian, pp. 15-25, Islamic Parliament Research Center, New York Times) More than 25 years after his death, Khomeini’s philosophies and teachings continue to influence all levels of Iran’s political system, including Iran’s legislative and presidential elections. In an interview with Iran’s Press TV, London-based professor of Islamic studies Mohammad Saeid Bahmanpoor said that Khomeini “has become a concept. -

Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region

KURDISTAN RISING? CONSIDERATIONS FOR KURDS, THEIR NEIGHBORS, AND THE REGION Michael Rubin AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region Michael Rubin June 2016 American Enterprise Institute © 2016 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any man- ner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. The views expressed in the publications of the American Enterprise Institute are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. American Enterprise Institute 1150 17th St. NW Washington, DC 20036 www.aei.org. Cover image: Grand Millennium Sualimani Hotel in Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan, by Diyar Muhammed, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons. Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Who Are the Kurds? 5 2. Is This Kurdistan’s Moment? 19 3. What Do the Kurds Want? 27 4. What Form of Government Will Kurdistan Embrace? 56 5. Would Kurdistan Have a Viable Economy? 64 6. Would Kurdistan Be a State of Law? 91 7. What Services Would Kurdistan Provide Its Citizens? 101 8. Could Kurdistan Defend Itself Militarily and Diplomatically? 107 9. Does the United States Have a Coherent Kurdistan Policy? 119 Notes 125 Acknowledgments 137 About the Author 139 iii Executive Summary wo decades ago, most US officials would have been hard-pressed Tto place Kurdistan on a map, let alone consider Kurds as allies. Today, Kurds have largely won over Washington. -

Power Projection and Force Deployment Under Reagan

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons War and Society (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses Fall 12-20-2019 The Ladle and the Knife: Power Projection and Force Deployment under Reagan Mathew Kawecki Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/war_and_society_theses Part of the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Kawecki, Mathew. The Ladle and the Knife: Power Projection and Force Deployment under Reagan. 2019. Chapman University, MA Thesis. Chapman University Digital Commons, https://doi.org/10.36837/ chapman.000095 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in War and Society (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ladle and the Knife: Power Projection and Force Deployment under Reagan A Thesis by Mathew D. Kawecki Chapman University Orange, CA Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in War and Society Studies December 2019 Committee in charge: Gregory Daddis, Ph.D., Chair Robert Slayton, Ph.D. Alexander Bay, Ph.D. The thesis ofMathew D. Kawecki is approved. Ph.D., Chair Eabert Slalton" Pir.D AlexanderBa_y. Ph.D September 2019 The Ladle and the Knife: Power Projection and Force Deployment under Reagan Copyright © 2019 by Mathew D. Kawecki III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Greg Daddis, for his academic mentorship throughout the thesis writing process. -

Won't You Be My Neighbor

Won’t You Be My Neighbor: Syria, Iraq and the Changing Strategic Context in the Middle East S TEVEN SIMON Council on Foreign Relations March 2009 www.usip.org Date www.usip.org UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE – WORKING PAPER Won’t You Be My Neighbor UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE 1200 17th Street NW, Suite 200 Washington, DC 20036-3011 © 2009 by the United States Institute of Peace. The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace, which does not advocate specific policy positions. This is a working draft. Comments, questions, and permission to cite should be directed to the author ([email protected]) or [email protected]. This is a working draft. Comments, questions, and permission to cite should be directed to the author ([email protected]) or [email protected]. UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE – WORKING PAPER Won’t You Be My Neighbor About this Report Iraq's neighbors are playing a major role—both positive and negative—in the stabilization and reconstruction of post-Saddam Iraq. In an effort to prevent conflict across Iraq's borders and in order to promote positive international and regional engagement, USIP has initiated high-level, non-official dialogue between foreign policy and national security figures from Iraq, its neighbors and the United States. The Institute’s "Iraq and its Neighbors" project has also convened a group of leading specialists on the geopolitics of the region to assess the interests and influence of the countries surrounding Iraq and to explain the impact of these transformed relationships on U.S. -

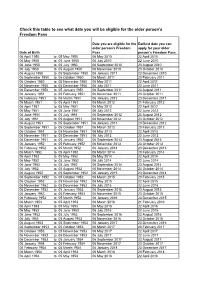

Copy of Age Eligibility from 6 April 10

Check this table to see what date you will be eligible for the older person's Freedom Pass Date you are eligible for the Earliest date you can older person's Freedom apply for your older Date of Birth Pass person's Freedom Pass 06 April 1950 to 05 May 1950 06 May 2010 22 April 2010 06 May 1950 to 05 June 1950 06 July 2010 22 June 2010 06 June 1950 to 05 July 1950 06 September 2010 23 August 2010 06 July 1950 to 05 August 1950 06 November 2010 23 October 2010 06 August 1950 to 05 September 1950 06 January 2011 23 December 2010 06 September 1950 to 05 October 1950 06 March 2011 20 February 2011 06 October 1950 to 05 November 1950 06 May 2011 22 April 2011 06 November 1950 to 05 December 1950 06 July 2011 22 June 2011 06 December 1950 to 05 January 1951 06 September 2011 23 August 2011 06 January 1951 to 05 February 1951 06 November 2011 23 October 2011 06 February 1951 to 05 March 1951 06 January 2012 23 December 2011 06 March 1951 to 05 April 1951 06 March 2012 21 February 2012 06 April 1951 to 05 May 1951 06 May 2012 22 April 2012 06 May 1951 to 05 June 1951 06 July 2012 22 June 2012 06 June 1951 to 05 July 1951 06 September 2012 23 August 2012 06 July 1951 to 05 August 1951 06 November 2012 23 October 2012 06 August 1951 to 05 September 1951 06 January 2013 23 December 2012 06 September 1951 to 05 October 1951 06 March 2013 20 February 2013 06 October 1951 to 05 November 1951 06 May 2013 22 April 2013 06 November 1951 to 05 December 1951 06 July 2013 22 June 2013 06 December 1951 to 05 January 1952 06 September 2013 23 August 2013 06 -

Iran and the Islamic Revolution International Relations 1802Q Brown University Fall 2018

Iran and the Islamic Revolution International Relations 1802Q Brown University Fall 2018 Instructor: Stephen Kinzer Office: Watson Institute, Room 308 Office Hours: Wednesdays 10-12 Email: [email protected] Class Meeting: Wednesdays 3-5:30, Watson Institute 112 Course Description The overthrow of Mohammad Reza Shah in 1979 and the subsequent emergence of the Islamic Republic of Iran shook the Middle East and reshaped global politics. These events have continued to reverberate for four decades, in ways that no one could have predicted. Hostility between the US and Iran has remained almost constant during this period. Yet despite the growing importance of Iran, few Americans know much about the country or its modern history. The shattering events of 1978-80 in Iran unfolded against the backdrop of the previous decades of Iranian history, so knowing that history is essential to understanding what has become known as the Islamic Revolution. Nor can the revolution be appreciated without studying the enormous effects it has had over the last 39 years. This seminar will place the anti-Shah movement and the rise of religious power in the context of Iran's century of modern history. We will conclude by focusing on today's Iran, including the upheaval that followed the 2009 election, the election of a reformist president in 2013, the breakthrough nuclear deal of 2015, and the United States’ withdrawal from the deal three years later. This seminar is unfolding as the United States launches a multi-faceted global campaign against Iran. Given the urgency of this escalating crisis, we will devote a portion of every class to discussion of the past week’s events.