Museum of Arts and Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arts in Seattle

ARTS IN SEATTLE ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN ................................................................................................................................2 EXPERIENCE MUSIC PROJECT..........................................................................................................................................2 SEATTLE PUBLIC LIBRARY , CENTRAL..............................................................................................................................4 SMITH TOWER ......................................................................................................................................................................5 CHAPEL OF ST. IGNATIUS ..................................................................................................................................................7 OLYMPIC SCULPTURE PARK ..............................................................................................................................................9 SEATTLE ART MUSEUM....................................................................................................................................................11 GAS WORKS PARK ............................................................................................................................................................12 SPACE NEEDLE..................................................................................................................................................................13 SEATTLE ARCHITECTURE FOUNDATION, -

MAKING IT PERSONAL a Creative Couple in Portland, Oregon Hired High-Profile Architect Brad Cloepfil to Renovate a Home Designed by Pietro Belluschi in the 1930S

MAKING IT PERSONAL A creative couple in Portland, Oregon hired high-profile architect Brad Cloepfil to renovate a home designed by Pietro Belluschi in the 1930s. WHEN JOHN AND JANET JAY and their two sons moved to Portland, Oregon, from New York City in 1993, they weren’t looking for a midcentury-modern home. “We were thinking perhaps colonial or arts and crafts,” chuckles John, who is the executive creative director for Wieden + Kennedy advertising. But serendipity arrived courtesy of Diane von Furstenberg, with whom Janet—a developer of fragrances and cosmetics— was working at the time. (Together, the husband and wife team run Studio J, an interdisciplinary design salon.) “Diane told me, ‘I know someone there, and they just happen to be selling their house,’” Janet remembers. It turned out the home’s original architect, Italian-born Pietro Belluschi, was a pioneer of Northwest modernism, defined by its combination of clean lines and open spaces with warm, natural materials, particularly wood. He also designed the Portland Art Museum and the Juilliard School at Lincoln Center. Completed in 1937, the house the Jays bought showed the influence of Frank Lloyd Wright in its slivered-brick exterior, tall strips of windows and open floor plan. Nestled onto a sloping site, the U-shaped house wrapped around a small courtyard. The interiors were suffused with light, with each of the three principal wings (bedrooms, living area and dining room/kitchen) having windows on at least two sides. Still, the house needed work. A previous renovation had created a caricature of Belluschi’s original design: The curving bay window in the courtyard, for example, was replicated in other windows. -

Eleven Madison Park to Open Renovated and Redesigned Home by Allied Works on October 8, 2017

Eleven Madison Park to Open Renovated and Redesigned Home By Allied Works on October 8, 2017 Redesign of Iconic New York Institution Infuses Original Art Deco Aesthetic With Custom Designs Inspired by Textures and Forms of Madison Square Park New York City—August 29, 2017—On October 8, 2017, Eleven Madison Park opens the doors to its newly redesigned home, following a comprehensive renovation by Allied Works Architecture. Reflecting Allied Works’ commitment to innovative and eloquent design across scales, the project encompasses the entire restaurant—from the interior architecture of the dining room to the creation of custom furniture, tableware, and textiles. Developed in close collaboration with restauranteur Will Guidara and Chef Daniel Humm, the restaurant’s co-owners, the redesign serves to further elevate the dining experience of the Three Michelin star–restaurant, recently named the “World’s Best Restaurant.” “Our design aims to preserve and enhance the character and beauty of Eleven Madison’s historic space and to celebrate the ritual of dining at every level,” said Allied Works principal Brad Cloepfil. “Since I first met Will in 2008, I have watched his and Chef Daniel’s vision for the restaurant crystalize—the warmth and precise attention to detail that result from Will’s views of hospitality and Chef’s elemental approach to food, where brilliantly concise and clear flavors are amplified through juxtaposition. The renovated Eleven Madison Park draws on these defining traits to create a unified dining experience—from food to fork, atmosphere to architectural envelop—and reinforces the restaurant’s standing as a contemporary and timeless New York icon.” The renovation honors and enhances the original Art Deco design of the room, once the lobby of the landmark Metropolitan Life building, by preserving defining features and amplifying original detail, with entirely new designs in the dining realm—including custom tableware, seating designs, and hand-tufted rugs, all designed for the restaurant by Allied Works. -

Buildings May Be Created to Last, but Little Else Stands Still in the World of Architecture

H >next Buildings may be created to last, but little else stands still in the world of architecture. Here we look at the best projects that are taking shape, creating a buzz and inspiring awe around the globe. You could say they’re floor plans for the future. COURTESY WILL ALSOP/MORLEY VON STERNBERG | ALLIED WORKS ARCHITECTURE | ALEKSANDRA KASUBA/JOHN JEHEBER | BATES MAHER/ROS KAVANAG COURTESY WILL ALSOP/MORLEY VON STERNBERG | ALLIED WORKS ARCHITECTURE ALEKSANDRA KASUBA/JOHN JEHEBER BATES 092 next_17.qxd 4/5/06 2:23 PM Page 92 > next ABOVE The always inventive Will Alsop. TOP ROW Note the characteristic bold colours and the extraordinary pods suspended from the ceiling. The giant orange molecule is called the Centre of the Cell (a learning centre for children). LEFT Cloud and, in the background, the dramatic, star-like structure of Spikey (meeting rooms). There is also a glass rectilinear beam of cellular offices and a meet and greet Mushroom pod. OPPOSITE PAGE Alsop’s long-term friend, artist Bruce McLean, created the large opaque artwork panels inspired by molecular science. PHOTOGRAPHY: MORLEY VON STERNBERG PHOTOGRAPHY: BLIZARD BUILDING LOCATION Queen Mary University of London, Whitechapel, London ARCHITECT Will Alsop, Alsop Design Ltd with AMEC COMPLETED 2005 This spectacular medical school consists of a three storey glass pavilion linked by a multi-coloured glass bridge to the “Wall of Plant”, a smaller, six storey, narrow structure so-called for its mechanical and electrical plant. Six metres below street level, some 400 scientists sit in a 3800m2 open plan area. The space is designed to better integrate the disciplines and thus create better scientific outcomes. -

Graham Foundation Announces 2015 Grants to Individuals

Graham Foundation Announces 2015 Grants to Individuals Over $490,000 awarded to individuals around the world to support new and challenging ideas in architecture. Noritaka Minami, Facade I, 2011, Tokyo, Japan. Courtesy of the artist. From the 2015 Individual Grant to Noritaka Minami and Ken Yoshida for 1972–Nakagin Capsule Tower. Chicago, May 27, 2015—An exhaustive photographic survey of modernist architect Le Corbusier’s completed architectural works, an exhibition exploring the visionary play environments created by a pioneering French design collective in the late 1960s, and a multimedia, online oral history chronicling the efforts to build housing for homeless individuals living with HIV and AIDS in New York City are among the newest projects to receive individual grants from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, the foundation announced today. In its first major grant announcement of 2015, the Graham Foundation will award over $490,000 to support 63 outstanding projects by individuals that engage original ideas in architecture. Among the funded projects are exhibitions, publications, multimedia archives, documentary films, podcasts, symposia, participatory workshops, and live performances. These diverse projects advance new scholarship in the field of architecture, fuel creative experimentation and critical dialogue, and expand opportunities for public engagement with architecture and its role in contemporary society. The awarded projects were selected from a competitive pool of 600 submissions from individuals representing 36 countries. The new grantees comprise a diverse group of architects, artists, designers, filmmakers, scholars, educators, curators, and writers around the world in cities such as Istanbul, Montreal, Tokyo, and Chicago, where the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts Madlener House, 4 West Burton Place, Chicago, Illinois 60610 T 312-787-4071 F 312-787-6350 [email protected] www.grahamfoundation.org Graham Foundation is based. -

National Music Centre of Canada Completes Its New Home, Studio Bell, Designed by Allied Works Architecture October 2016

National Music Centre of Canada Completes its New Home, Studio Bell, Designed by Allied Works Architecture October 2016 Exterior rendering of Studio Bell, the new home of the National Music Centre. Image © Mir. New York, New York (September 29, 2016) – The National Music Centre (NMC) of Canada celebrates the completion of Studio Bell, its new home and the latest cultural project designed by Allied Works Architecture (AWA). The new state-of-the-art cultural center is at once a performance hall, recording facility, broadcast studio, live music venue and museum—the first facility of its kind in North America and the first to be dedicated to music in Canada in all of its forms. Located in Calgary, Alberta, at the site of the legendary blues club in the historic King Edward Hotel, Studio Bell connects visitors with Canada’s rich musical history through live performances, exhibitions, and interactive education programs. Local audiences have been able to preview the new center through a phased launch of exhibitions and programs beginning in July, culminating in the institution’s programmatic and architectural completion at the end of October. Marking Allied Works’ most ambitious building project to date, Studio Bell rises in nine, interlocking towers, clad in glazed terra cotta. Its subtly curved design references acoustic vessels, while allowing for sweeping views of the Stampede Park, Bow River and surrounding cityscape. The project encompasses 160,000-square-feet of new construction, including a 300-seat performance hall and 22,000-square-feet of exhibition space. The masonry building of the “King Eddy” has been fully refurbished and integrated within the NMC’s program in Studio Bell’s west block, which features a radio station, recording studios, media center, Artists-in-Residence spaces, and education classrooms. -

Immersive Installation of Sculptures and Drawings by Allied Works Architecture Spotlights Rarely Seen Aspect of Firm’S Creative Practice

Immersive Installation of Sculptures and Drawings by Allied Works Architecture Spotlights Rarely Seen Aspect of Firm’s Creative Practice Major Traveling Exhibition Opens at Portland Art Museum Next Month Installation shot of Case Work: Studies in Form, Space, & Construction by Brad Cloepfil / Allied Works Architecture at the Denver Art Museum, 2016. Photo by Stephan Alessi. New York City—May 17, 2016—Following its debut at the Denver Art Museum this January, the first comprehensive exhibition exploring the architectural sculptures and drawings of Allied Works Architecture will open at the Portland Museum June 4, on view through September 4, 2016. Presented within an immersive installation designed by Allied Works, the exhibition features a cross-section of over 60 works made over the past 15 years, the majority of which have never been presented publicly. A counterpoint to the customary building models and technical architectural renderings, these works are both singular artistic creations and manifestations of the investigative process that is at the heart of the firm’s practice. Case Work: Studies in Form, Space & Construction by Brad Cloepfil/Allied Works Architecture was organized by the Clyfford Still Museum and the Portland Art Museum in association with Allied Works. “Case Work highlights a little-known part of Allied Works’ practice—namely the handmade works of art developed to articulate, inform, and accelerate the firm’s creative vision,” explained exhibition curator Dean Sobel, a specialist in modern and contemporary art and the director of the Clyfford Still Museum, which was designed by Allied Works. “These sculptures and gestural sketches are a pivotal part of the investigative process that distinguishes the firm’s approach. -

Within and Among

Oz Volume 37 Article 7 1-1-2015 Within and Among Brad Cloepfil Allied Works Architecture Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/oz Part of the Architecture Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Cloepfil, Brad (2015) "Within and Among," Oz: Vol. 37. https://doi.org/10.4148/2378-5853.1545 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oz by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Within and Among Brad Cloepfil Allied Works Architecture Architecture begins with a site. As architects we act upon a site and simultaneously, forces of culture and time act upon the buildings we create. Site is the potential of building, the field or range of forces (environmental) and opportunities (experiential) that exist in a place. Sites are physical, topographical, environmental, but they are also cultural and institutional. Where all sites carry the same value, built or un-built, urban or rural—each site holds a specific possibility. Architec- ture must be cultivated from the site, rising up out of the existing forces. —Brad Cloepfil, Occupation Occupation The existing forces embodied by a site are what we commonly refer to as con- text. An awareness of context implies a relative positioning of the self. I am here, among these buildings, or within this field, at this place in the history of ideas and technology. In acknowledg- ing surroundings as specific, as forged or affected by particular physical or cultural forces, experiences or quali- ties, you have begun a conversation of context. -

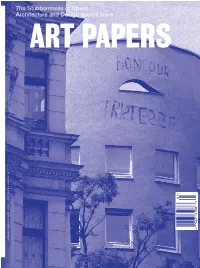

The Stubbornness of Space Architecture and Design Special Issue

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2015 39/01 US $7 CAAN $9 UK £66 EUU €8 Architecture andDesignspecialissue The StubbornnessofSpace ART PAPERS ART 3 Multiple 48 Strange Shapes Letter from the GuestGuest EditorEditor david reinfurt (o-r-g) mtwtf This issue is aboutout spacespacece andan place, and various What does it mean to make One person one vote — sort of. attempts to engagegage or overcomeoverovercc them. In my old an artist’s multiple now? A design commission considers neighborhood inn SanSan Francisco,Franciranciss controversy roils over A software commission. the geometry of gerrymandering. rising rents, no-faultfault evictions,evictioctionn and clashing cultures, as Silicon Valleyy companiesanies move northward into a 14 Logistics Make the World 50 The Knoll Transcripts historically diverserse city. BeyBeyoBeyondo issues of gentrifica- jesse lecavalier margot weller tion, or the neighborlinesshborlinessess ofof corporations, the conflict has improbable roots inn the region.r Fred Turner’s book Synchronizing the world of Previously unpublished From Counterculture1ulture too CybercultureCyCybb (2006) charts commerce means attempting interviews with Knoll designers the evolution from the Bay Area communes of the to overcome time and space. revise the story of midcentury 1960s to the Silicon Valley of the 1990s. This evolution A study of logistics with a photo modernism. was premised on a belief in the power of networked essay on UPS. information technologies to emancipate users from 58 Concept Models body and physical space — if sometimes to the ne- 22 Losing Interest allied works architecture glect of the social, political, and environmental infra- shumon basar structures that support them. Turner’s social critique Beyond site or program, these has new salience in a moment of social media. -

For Immediate Release the Architectural League of New York

For immediate release The Architectural League of New York Awards the 2018 President’s Medal to Christiana Figueres League lauds visionary leader on climate change June 25, 2018 The Architectural League At a June 20 dinner in New York, Architectural League President Billie Tsien awarded the League’s 2018 of New York 594 Broadway, Suite 607 President’s Medal to Christiana Figueres. As Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention New York, NY 10012 on Climate Change (UNFCCC), she led the nations of the world to achieve the 2015 Paris Agreement. 212 753 1722 [email protected] archleague.org The President’s Medal is The Architectural League’s highest honor and is bestowed, at the discretion of the League’s President and Board of Directors, on individuals to recognize extraordinary achievements in For additional information and photographs of the architecture, urbanism, art, design, and the environment. night’s event, contact: The Architectural League honored Christiana Figueres for her courageous, imaginative, indefatigable work on Jordan Hruska Communications Director behalf of our planetary home. 212.753.1722, ext. 16 [email protected] Architect and technological innovator Anna Dyson, founding director of Yale Center for Ecosystems in Architecture; conservation ecologist Eric Sanderson, author of Mannahatta; and landscape architect and MacArthur Fellow Kate Orff, along with Ms. Tsien and League executive director Rosalie Genevro celebrated Figueres with remarks. Eric Sanderson said: “When she has the ear of presidents and business people and power brokers on the global stage – including all of you tonight – her optimism creates a platform for connection. It enables us to do what we really did want to do after all, to sign up to voluntarily reduce our greenhouse gas emissions and work together to transparently measure our progress. -

Allied Works Architecture David Baker + Partners Behnisch Architekten

→DESIGN ALLIED WORKS ARCHITECTURE 150 DAVID BAKER + PARTNERS 160 BEHNISCH ARCHITEKTEN 168 CLYFFORD STILL MUSEUM DENVER ALLIED WORKS ARCHITECTURE TEXT BY AARON BETSKY PHOTOS BY BRUCE DAMONTE DEsign→ FIRM 153 A Denver, the Mile high City, is actually a city of the plains. That was the crucial R CH realization that led architect Brad Cloepfil, AIA, of Allied Works Architecture in Portland, ITE Ore., to design the new Clyfford Still Museum as a solitary object sheltered behind C T a screen of sycamore trees, like a homestead found in the windswept flatness that 2012 JANUARY stretches out to the east, north, and south of the site. This 28,500-square-foot monument is now the permanent home for Still’s quintessential brand of American Abstract Expressionist works. The Still Museum houses more than 800 paintings and more than 1,500 works on paper that the artist left to his estate. Still, who died in 1980 at age 75, was a difficult man and a complex painter who spent the last two decades of his life in near seclusion in rural Maryland, having essentially withdrawn his work from the gallery system. His will reserved the rest of his estate for whichever city would build a purpose-built structure to permanently house his—and only his—works. In 2004, the City of Denver and some of its leading citizens pledged to do just that, and have raised $32 million to date for the building’s construction. The newly formed Clyfford Still Museum selected Brad Cloepfil in a limited competition in 2006. The 2008 recession led to a construction slowdown, as well as a 10 percent reduction of the building’s remaining mass—a basement level had already been eliminated. -

1996–2019 Indici 632–906

1996–2019 indici 632–906 inserto redazionale di Casabella 2020 in consultazione esclusiva su: http://casabellaweb.eu direttore responsabile Francesco Dal Co coordinamento Alessandra Pizzochero progetto Tassinari/Vetta © Copyright 2020 Mondadori Media Tutti i diritti di proprietà artistica e letteraria riservati CASABELLA 632 anno LX marzo 1996 Decidere Venezia Béla Lajta e i suoi angeli L’ornamento Casabella 632 p. II Il restauro del cabaret Parisiana Ananda K. Coomaraswamy a Budapest Casabella 632 p. 62 Editoriale Marco Biraghi Francesco Dal Co Casabella 632 p. 50 News Casabella 632 p. 1 Casabella 632 p. 76 Il restauro del Parisiana e la Frank O. Gehry conservazione dell’architettura Bits Il museo Guggenheim a Bilbao contemporanea Selezione di siti www in costruzione Marco Biraghi a cura di Sergio Polano Casabella 632 p. 2 Casabella 632 p. 54 Casabella 632 p. 76 Il rivestimento di Frank O. Gehry, Libri & Riviste Digital publishing o della lamina elastica Roberto Gargiani La scuola del silenzio «Artifice» Casabella 632 p. 4 Marc Fumaroli quadrimestrale con cd-rom accluso traduzione di Margherita Botto di “architettura, cinema, fotografia, Contro il razionalismo settario, 1947 Adelphi, Milano 1995 design, arte”, Artifice, London, UK Sigfried Giedion ed. or. L’École du silence, Casabella 632 p. 77 Casabella 632 p. 14 Flammarion, Paris 1994 Casabella 632 p. 60 Richard Meier Architect Hans Kollhoff cd-rom della collana Contemporary Isolato in Malchower Weg a Berlino 1994 Louis Henry Sullivan 1856–1924 Architects and Designers, Casabella 632 p. 16 Mario Manieri Elia Victory Interactive Media, Electa, Milano 1995 Lugano, Svizzera Le qualità del banale Casabella 632 p.