Redefining an Eagle—Suhel Quader Parry, S.J., Clark, W.S., And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Multi-Gene Phylogeny of Aquiline Eagles (Aves: Accipitriformes) Reveals Extensive Paraphyly at the Genus Level

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com MOLECULAR SCIENCE•NCE /W\/Q^DIRI DIRECT® PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION ELSEVIER Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 35 (2005) 147-164 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A multi-gene phylogeny of aquiline eagles (Aves: Accipitriformes) reveals extensive paraphyly at the genus level Andreas J. Helbig'^*, Annett Kocum'^, Ingrid Seibold^, Michael J. Braun^ '^ Institute of Zoology, University of Greifswald, Vogelwarte Hiddensee, D-18565 Kloster, Germany Department of Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 4210 Silver Hill Rd., Suitland, MD 20746, USA Received 19 March 2004; revised 21 September 2004 Available online 24 December 2004 Abstract The phylogeny of the tribe Aquilini (eagles with fully feathered tarsi) was investigated using 4.2 kb of DNA sequence of one mito- chondrial (cyt b) and three nuclear loci (RAG-1 coding region, LDH intron 3, and adenylate-kinase intron 5). Phylogenetic signal was highly congruent and complementary between mtDNA and nuclear genes. In addition to single-nucleotide variation, shared deletions in nuclear introns supported one basal and two peripheral clades within the Aquilini. Monophyly of the Aquilini relative to other birds of prey was confirmed. However, all polytypic genera within the tribe, Spizaetus, Aquila, Hieraaetus, turned out to be non-monophyletic. Old World Spizaetus and Stephanoaetus together appear to be the sister group of the rest of the Aquilini. Spiza- stur melanoleucus and Oroaetus isidori axe nested among the New World Spizaetus species and should be merged with that genus. The Old World 'Spizaetus' species should be assigned to the genus Nisaetus (Hodgson, 1836). The sister species of the two spotted eagles (Aquila clanga and Aquila pomarina) is the African Long-crested Eagle (Lophaetus occipitalis). -

Melagiris (Tamil Nadu)

MELAGIRIS (TAMIL NADU) PROPOSAL FOR IMPORTANT BIRD AREA (IBA) State : Tamil Nadu, India District : Krishnagiri, Dharmapuri Coordinates : 12°18©54"N 77°41©42"E Ownership : State Area : 98926.175 ha Altitude : 300-1395 m Rainfall : 620-1000 mm Temperature : 10°C - 35°C Biographic Zone : Deccan Peninsula Habitats : Tropical Dry Deciduous, Riverine Vegetation, Tropical Dry Evergreen Proposed Criteria A1 (Globally Threatened Species) A2 (Endemic Bird Area 123 - Western Ghats, Secondary Area s072 - Southern Deccan Plateau) A3 (Biome-10 - Indian Peninsula Tropical Moist Forest, Biome-11 - Indo-Malayan Tropical Dry Zone) GENERAL DESCRIPTION The Melagiris are a group of hills lying nestled between the Cauvery and Chinnar rivers, to the south-east of Hosur taluk in Tamil Nadu, India. The Melagiris form part of an almost unbroken stretch of forests connecting Bannerghatta National Park (which forms its north-western boundary) to the forests of Cauvery Wildlife Sanctuary - Karnataka (which forms its southern boundary, separated by the river Cauvery), and further to Biligirirangan hills and Sathyamangalam forests. The northern and western parts are comparatively plain and is part of the Mysore plateau. The average elevation in this region is 500-1000 m. Ground sinks to 300m in the valley of the Cauvery and the highest point is the peak of Guthereyan at 1395.11 m. Red sandy loam is the most common soil type found in this region. Small deposits of alluvium are found along Cauvery and Chinnar rivers and Kaoline is found in some areas near Jowlagiri. The temperature ranges from 10°C ± 35°C. South-west monsoon is fairly active mostly in the northern areas, but north-east monsoon is distinctly more effective in the region. -

Spread-Wing Postures and Their Possible Functions in the Ciconiidae

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY Von. 88 Oc:roBE'a 1971 No. 4 SPREAD-WING POSTURES AND THEIR POSSIBLE FUNCTIONS IN THE CICONIIDAE M. P. KAI-IL IN two recent papers Clark (19'69) and Curry-Lindahl (1970) have reported spread-wingpostures in storks and other birds and discussed someof the functionsthat they may serve. During recent field studies (1959-69) of all 17 speciesof storks, I have had opportunitiesto observespread-wing postures. in a number of speciesand under different environmentalconditions (Table i). The contextsin which thesepostures occur shed somelight on their possible functions. TYPES OF SPREAD-WING POSTURES Varying degreesof wing spreadingare shownby at least 13 species of storksunder different conditions.In somestorks (e.g. Ciconia nigra, Euxenuragaleata, Ephippiorhynchus senegalensis, and ]abiru mycteria) I observedno spread-wingpostures and have foundno referenceto them in the literature. In the White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) I observedonly a wing-droopingposture--with the wings held a short distanceaway from the sidesand the primaries fanned downward--in migrant birds wetted by a heavy rain at NgorongoroCrater, Tanzania. Other species often openedthe wingsonly part way, in a delta-wingposture (Frontis- piece), in which the forearmsare openedbut the primariesremain folded so that their tips crossin front o.f or below the. tail. In some species (e.g. Ibis leucocephalus)this was the most commonly observedspread- wing posture. All those specieslisted in Table i, with the exception of C. ciconia,at times adopted a full-spreadposture (Figures i, 2, 3), similar to those referred to by Clark (1969) and Curry-Lindahl (1970) in severalgroups of water birds. -

2018 Cambodia & South Vietnam Species List

Cambodia and South Vietnam Leader: Barry Davies Eagle-Eye Tours January 2018 Seen/ Common Name Scientific Name Heard DUCKS, GEESE, AND WATERFOWL 1 Lesser Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna javanica s 2 Comb Duck Sarkidiornis melanotos s 3 Cotton Pygmy-Goose Nettapus coromandelianus s 4 Indian Spot-billed Duck Anas poecilorhyncha s 5 Garganey Anas querquedula s PHEASANTS, GROUSE, TURKEYS, ALLIES 6 Chinese Francolin Francolinus pintadeanus s 9 Scaly-breasted Partridge Arborophila chloropus s 11 Red Junglefowl Gallus gallus s 13 Siamese Fireback Lophura diardi s 14 Germain's Peacock-Pheasant Polyplectron germaini s 16 Green Peafowl Pavo muticus s GREBES 17 Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis s STORKS 18 Asian Openbill Anastomus oscitans s 19 Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus s 21 Painted Stork Mycteria leucocephala s CORMORANTS AND SHAGS 22 Indian Cormorant Phalacrocorax fuscicollis s 23 Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo s 24 Little Cormorant Microcarbo niger s ANHINGAS 25 Oriental Darter Anhinga melanogaster s PELICANS 26 Spot-billed Pelican Pelecanus philippensis s HERONS, EGRETS, AND BITTERNS 28 Cinnamon Bittern Ixobrychus cinnamomeus s 30 Gray Heron Ardea cinerea s 31 Purple Heron Ardea purpurea s 32 Eastern Great Egret Ardea (alba) modesta s 33 Intermediate Egret Ardea intermedia s 34 Little Egret Egretta garzetta s 35 (Eastern) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis coromandus s IBISES AND SPOONBILLS 41 White-shouldered Ibis Pseudibis davisoni s 42 Black-headed Ibis Threskiornis melanocephallus s 43 Giant Ibis Pseudibis gigantea s OSPREY 44 Osprey -

Bird Checklists of the World Country Or Region: Myanmar

Avibase Page 1of 30 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Myanmar 2 Number of species: 1088 3 Number of endemics: 5 4 Number of breeding endemics: 0 5 Number of introduced species: 1 6 7 8 9 10 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2021. Checklist of the birds of Myanmar. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=mm [23/09/2021]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird. -

India: Kaziranga National Park Extension

INDIA: KAZIRANGA NATIONAL PARK EXTENSION FEBRUARY 22–27, 2019 The true star of this extension was the Indian One-horned Rhinoceros (Photo M. Valkenburg) LEADER: MACHIEL VALKENBURG LIST COMPILED BY: MACHIEL VALKENBURG VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM INDIA: KAZIRANGA NATIONAL PARK EXTENSION February 22–27, 2019 By Machiel Valkenburg This wonderful Kaziranga extension was part of our amazing Maharajas’ Express train trip, starting in Mumbai and finishing in Delhi. We flew from Delhi to Guwahati, located in the far northeast of India. A long drive later through the hectic traffic of this enjoyable country, we arrived at our lodge in the evening. (Photo by tour participant Robert Warren) We enjoyed three full days of the wildlife and avifauna spectacles of the famous Kaziranga National Park. This park is one of the last easily accessible places to find the endangered Indian One-horned Rhinoceros together with a healthy population of Asian Elephant and Asiatic Wild Buffalo. We saw plenty individuals of all species; the rhino especially made an impression on all of us. It is such an impressive piece of evolution, a serious armored “tank”! On two mornings we loved the elephant rides provided by the park; on the back of these attractive animals we came very close to the rhinos. The fertile flood plains of the park consist of alluvial silts, exposed sandbars, and riverine flood-formed lakes called Beels. This open habitat is not only good for mammals but definitely a true gem for some great birds. Interesting but common birds included Bar-headed Goose, Red Junglefowl, Woolly-necked Stork, and Lesser Adjutant, while the endangered Greater Adjutant and Black-necked Stork were good hits in the stork section. -

(Anastomus Oscitans) in ASSAM, INDIA Journal of Global Biosciences

Journal of Global Biosciences ISSN 2320-1355 Volume 5, Number 6, 2016, pp. 4188-4196 Website: www.mutagens.co.in E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Research Paper FOOD AND FEEDING BEHAVIOUR OF OPENBILL STORK ( Anastomus oscitans ) IN ASSAM, INDIA Jinnath Anam #, Mansur Ahmed #, M. K. Saikia* and P.K. Saikia $ # Research Scholar, Animal Ecology and Wildlife Biology lab, * Assistant Professor, Department of Zoology, Animal Ecology & Wildlife Biology Lab, Gauhati University, Gopinath Bardoloi Nagar, Jalukbari, Guwahati-781014, Assam, India $Professor, Department of Zoology, Animal Ecology & Wildlife Biology Lab. Gauhati University. Abstract Open bill stork characterized by having large bills, with a gap of mandibles in middle. The present article mainly emphasized the feeding ecology of the open bill storks, emphasized on feeding behaviour, techniques and strategies of feeding and types and availability of prey species in the Brahmaputra Valley, Assam. Wetlands (Beels) of Brahmaputra river system and harvested Paddy fields were the favourite foraging sites for open bill storks in non breeding seasons. It has been observed that during non breeding season open bill stork devoted maximum time in resting (35% of the active period) either on a high land or on roosting tree. 33% of the active time was utilized in search of food. Soaring was one of the important behaviour noticed in open bill stork. An open bill stork utilized 13% of the day active time in soaring behavior. Minimum time was used in aggression behaviour that includes chasing, threatening, snatching etc. Open bill storks feed molluscs and fishes and the types of prey never vary during summer and winter. -

Rapid Range Expansion of Asian Openbill Anastomus Oscitans in China QIANG LIU, PAUL BUZZARD & XU LUO

118 SHORT NOTES Forktail 31 (2015) References Li J. J., Han L. X., Cao H. F., Tian Y., Peng B. Y., Wang B. & Hu H. J. (2013) The BirdLife International (2001) Threatened birds of Asia: the BirdLife International fauna and vertical distribution of birds in Mount Qomolangma National Red Data Book. Cambridge UK: BirdLife International. Nature Reserve. Zool. Research 34(6): 531–548. (In Chinese with English BirdLife International (2015) Species factsheet: Grus nigricollis. Downloaded abstract.) from http://www.birdlife.org on 01/02/2015. Ma M., Li W. D., Zhang H. B., Zhang X., Yuan G. Y., Chen Y., Yuan L., Ding P., Bishop, M. A. & Tsamchu, D. (2007) Tibet Autonomous Region January 2007 Zhang Y., Cheng Y. & Sagen, G. L. (2011) Distribution and population survey for Black-necked Crane, Common Crane, and Bar-headed Goose. state of Black-necked Crane Grus nigricollis in Lop Nur and Kunlun Mts., China Crane News 11(1): 23–26. Southern Xinjiang. Chinese J. Zool. 46(3): 64–68. (In Chinese.) Dwyer, N. C., Bishop, M. A., Harkness, J. S. & Zhong Z. Y. (1992) Black-necked RSPN (2015) Report on annual Black-necked Crane count for Bhutan. <http:// Cranes nesting in Tibet Autonomous Region, China. Pp.75–80 in D. W. www.rspnbhutan.org/news-and-events/news/483-report-on-annual- Stahlecker & R. P. Urbanek, eds. Proceedings of the Sixth North American black-necked-crane-count-for-bhutan.html> Accessed in February 2015. Crane Workshop, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada, 3–5 October 1991. Grand Tsamchu, D., Yang, L., Li, J. C. & Yangjaen, D. -

India: Tigers, Taj, & Birds Galore

INDIA: TIGERS, TAJ, & BIRDS GALORE JANUARY 30–FEBRUARY 17, 2018 Tiger crossing the road with VENT group in background by M. Valkenburg LEADER: MACHIEL VALKENBURG LIST COMPILED BY: MACHIEL VALKENBURG VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM INDIA: TIGERS, TAJ, & BIRDS GALORE January 30–February 17, 2018 By Machiel Valkenburg This tour, one of my favorites, starts in probably the busiest city in Asia, Delhi! In the afternoon we flew south towards the city of Raipur. In the morning we visited the Humayan’s Tomb and the Quitab Minar in Delhi; both of these UNESCO World Heritage Sites were outstanding, and we all enjoyed them immensely. Also, we picked up our first birds, a pair of Alexandrine Parakeets, a gorgeous White-throated Kingfisher, and lots of taxonomically interesting Black Kites, plus a few Yellow-footed Green Pigeons, with a Brown- headed Barbet showing wonderfully as well. Rufous Treepie by Machiel Valkenburg From Raipur we drove about four hours to our fantastic lodge, “the Baagh,” located close to the entrance of Kanha National Park. The park is just plain awesome when it comes to the density of available tigers and birds. It has a typical central Indian landscape of open plains and old Sal forests dotted with freshwater lakes. In the early mornings when the dew would hang over the plains and hinder our vision, we heard the typical sounds of Kanha, with an Indian Peafowl displaying closely, and in the far distance the song of Common Hawk-Cuckoo and Southern Coucal. -

Assam Extension I 17Th to 21St March 2015 (5 Days)

Trip Report Assam Extension I 17th to 21st March 2015 (5 days) Greater Adjutant by Glen Valentine Tour leaders: Glen Valentine & Wayne Jones Trip report compiled by Glen Valentine Trip Report - RBT Assam Extension I 2015 2 Top 5 Birds for the Assam Extension as voted by tour participants: 1. Pied Falconet 4. Ibisbill 2. Greater Adjutant 5. Wedge-tailed Green Pigeon 3. White-winged Duck Honourable mentions: Slender-billed Vulture, Swamp Francolin & Slender-billed Babbler Tour Summary: Our adventure through the north-east Indian subcontinent began in the bustling city of Guwahati, the capital of Assam province in north-east India. We kicked off our birding with a short but extremely productive visit to the sprawling dump at the edge of town. Along the way we stopped for eye-catching, introductory species such as Coppersmith Barbet, Purple Sunbird and Striated Grassbird that showed well in the scopes, before arriving at the dump where large frolicking flocks of the endangered and range-restricted Greater Adjutant greeted us, along with hordes of Black Kites and Eastern Cattle Egrets. Eastern Jungle Crows were also in attendance as were White Indian One-horned Rhinoceros and Citrine Wagtails, Pied and Jungle Mynas and Brown Shrike. A Yellow Bittern that eventually showed very well in a small pond adjacent to the dump was a delightful bonus, while a short stroll deeper into the refuse yielded the last remaining target species in the form of good numbers of Lesser Adjutant. After our intimate experience with the sought- after adjutant storks it was time to continue our journey to the grassy plains, wetlands, forests and woodlands of the fabulous Kaziranga National Park, our destination for the next two nights. -

Kanha Survey Bird ID Guide (Pdf; 11

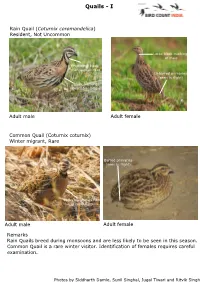

Quails - I Rain Quail (Coturnix coromandelica) Resident, Not Uncommon Lacks black markings of male Prominent black markings on face Unbarred primaries (seen in flight) Black markings (variable) below Adult male Adult female Common Quail (Coturnix coturnix) Winter migrant, Rare Barred primaries (seen in flight) Lacks black markings of male Rain Adult male Adult female Remarks Rain Quails breed during monsoons and are less likely to be seen in this season. Common Quail is a rare winter visitor. Identification of females requires careful examination. Photos by Siddharth Damle, Sunil Singhal, Jugal Tiwari and Ritvik Singh Quails - II Jungle Bush-Quail (Perdicula asiatica) Resident, Common Rufous and white supercilium Rufous & white Brown ear-coverts supercilium and Strongly marked brown ear-coverts above Rock Bush-Quail (Perdicula argoondah) Resident, Not Uncommon Plain head without Lacks brown ear-coverts markings Little or no streaks and spots above Remarks Jungle is typically more common than Rock in Central India. Photos by Nikhil Devasar, Aseem Kumar Kothiala, Siddharth Damle and Savithri Singh Crested (Oriental) Honey Buzzard (Pernis ptilorhynchus) Resident, Common Adult plumages: male (left), female (right) 'Pigeon-headed', weak bill Weak bill Long neck Long, slender Variable streaks and and weak markings below build Adults in flight: dark morph male (left), female (right) Confusable with Less broad, rectangular Crested Hawk-Eagle wings Rectangular wings, Confusable with Crested Serpent not broad Eagle Long neck Juvenile plumages Confusable -

Wave Moult of the Primaries in Accipitrid Raptors, and Its Use in Ageing Immatures

Chancellor, R. D. & B.-U. Meyburg eds. 2004 Raptors Worldwide WWGBP/MME Wave Moult of the Primaries in Accipitrid raptors, and its use in ageing immatures William S. Clark ABSTRACT Stresemann & Stresemann (1966) described wave moult in the primary remiges ('Staffelmauser' in German; also translated as 'step-wise moult') for some families of birds but not for Acccipitrid raptors, even though many of the species in this family (especially the larger ones) show it. Primaries of Accipitrid raptors are replaced from Pl (inner) sequentially outward. Waves are formed when not all of the ten primaries are replaced in any annual moult cycle. In the next annual cycle, moult begins anew at Pl as well as continuing with the next feather from where it left off in the last cycle. Two or three, occasionally four, wave fronts of new primaries can be seen in the primaries of some raptors, especially larger ones, e.g., eagles. Knowledge and understanding of wave moult can ascertain the ages of immature raptors in those species that take three or four years to attain adult plumage, as these species typically do not replace all of the primaries in any moult cycle. Juvenile eagles show all primaries the same age. Second plumage eagles show two ages of primaries, newer inner ones and older retained juvenile outer ones. Third plumage eagles show two waves, with the first wave proceeding to P8, P9, or PIO, and the second to P3, P4, P5, or P6. Fourth plumage eagles usually show new outer PlO from the first wave, new P5 to P7 from the second wave, and new Pl to P3 from the most recent wave.