The Union Party of 1936

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FATHER DIVINE. Father Divine Papers, Circa 1930-1996

FATHER DIVINE. Father Divine papers, circa 1930-1996 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Father Divine. Title: Father Divine papers, circa 1930-1996 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 840 Extent: 8 linear feet (16 boxes), 3 oversized papers papers boxes and 3 oversized papers folders (OP), 3 extra-oversized papers (XOP), 7 oversized bound volumes (OBV), and AV Masters: .25 linear feet (1 box) Abstract: Papers relating to African American evangelist Father Divine and the Peace Mission Movement including correspondence, writings, photographs, printed material, and memorabilia. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Separated Material Pamphlets, monographs and periodicals included in the collection have been cataloged separately. These materials may be located in the Emory University online catalog by searching for: Father Divine. Source Purchase, 1997, with subsequent additions. Citation [after identification of item(s)], Father Divine papers, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Father Divine papers, 1930-1996 Manuscript Collection No. 840 Processing Processed by Susan Potts McDonald, April 2011 In 2014, Emory Libraries conservation staff cleaned, repaired, and reformatted the scrapbooks numbered OBV1 and OBV2 as part of the National Parks Service funded Save America's Treasures grant to preserve African American scrapbooks in the Rose Library's holdings. -

Wheeler and the Montana Press

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1954 The court plan B. K. Wheeler and the Montana press Catherine Clara Doherty The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Doherty, Catherine Clara, "The court plan B. K. Wheeler and the Montana press" (1954). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 8582. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/8582 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TfflS OOCTBT PLAN, B. K. WHEELER AND THE MONTANA PRESS by CATHERINE C. DOHERTY B. A. , Montana State University, 1953 Presented In partial fulfillment ef the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1954 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: EP39383 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI OisMftaebn Ajbliehing UMI EP39383 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. -

Three Pictures Looking Through the Lens of Alumna Linda Panetta’S Life and Work

Fall 2010 • Volume 07 • Number 03 MAGAZINE Three picTures Looking through the Lens of aLumna Linda Panetta’s Life and work. Page 16 1 CALENDAR OF EVENTS Alumni Weekend 2010 Risa Vetri Ferman Cabrini Classic December 2 – January 18 Through the Lens: Student Work from Fine Arts Photography Graduate Programs Open Houses Grace and Joseph Gorevin Fine Arts Gallery, 2nd Floor, Holy Spirit Library Works by Cabrini College students in the Fine Arts Photography class. December 9, February 1, March 2, April 7 Admission is free. Information: www.cabrini.edu/fineartscalendar or call 610-902-8381. 6 p.m., Grace Hall Cabrini offers a Master of Education, a Master of Science in March 9 Leader Lecture Series—A Town Hall Meeting: Organization Leadership, and several teacher certifications. “Breaking the Glass Ceiling in Law Enforcement Leadership” To register or to schedule an appointment, 6:30 p.m., Grace Hall Boardroom visit www.cabrini.edu/gps or call 610-902-8500. Eileen Behr, Chief of Police, Whitemarsh Township, Pennsylvania Maureen Rush, Vice President for Public Safety, University of Pennsylvania Admission is free, but registration is requested: www.cabrini.edu/gps or May 23 call 610-902-8500. Sponsored by the Office of Graduate and Professional 22nd Annual Cabrini Classic Honoring Edith Robb Dixon HON’80 Studies. Waynesborough Country Club – Paoli, Pa. April 12 June 4-5 Leader Lecture Series—“Principles of Justice for Children” Alumni Weekend Risa Vetri Ferman, District Attorney, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania Classes of 1961, 1966, 1971, 1976, 1981, 1986, 1991, 1996, 2001, 6:30 p.m., Mansion and 2006 celebrate milestone reunions. -

Press Coverage of Father Charles E. Cougiilin and the Union Party by

PRESS COVERAGE OF FATHER CHARLES E. COUGIILIN AND THE UNION PARTY BY ,. FOUR METROPOLITAN DAILY NEWSPAPERS DURING THE ELECTION CAMPAIGN OF 1936: A STUDY Thesis for the Degree of M . A. MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY MES C. RAGAINS 1967 _ W“ Witt-95 2262.533 1 p- LU 9 1‘? 1923 '3 if." r Y‘Pi’v‘éfi“ I :- . J \ 1: .0 G‘ ‘73"; '- QNQFA IW“ _____.—————- ~ ABSTRACT PRESS COVERAGE OF FATHER CHARLES E. COUGHLIN AND THE UNION PARTY BY FOUR METROPOLITAN DAILY NEWSPAPERS DURING THE ELECTION CAMPAIGN OF 1936: A STUDY by Charles C. Ragains This study is the result of the writer's inter- est in the Reverend Father Charles E. Coughlin, a Roman Catholic priest who was pastor of a parish in Royal Oak, Michigan, and whose oratory attracted national attention and considerable controversy; in the political and social ferment in the United States during the 1930's; and in the American press. The questions that motivated the study were: How did the nation's newspapers react to Coughlin, who is regarded as one of the foremost dema- gogues in American history, at the height of his career? Did the press significantly affect the priest's influence and power one way or the other? How did newspapers in- terpret Coughlin and his actions to their readers? Because of the length of Coughlin's public career (nearly sixteen years) it has been necessary to select a salient event or period on which to concentrate. Charles C. Ragains The period selected is the presidential election campaign of 1936. This span of approximately five and one-half months was chosen for several reasons. -

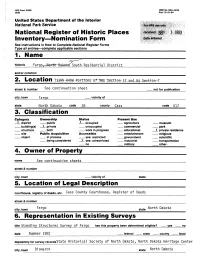

<A-~"-"' 3. Classification

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections 1. Name <A-~"-"' historic &H*e%a SouthSout Residential District and/or common 2. Location street & number See continuation sheet not for publication city, town Fargo vicinity of state North Dakota code 38 county Cass code 017 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use X district public X occupied agriculture museum building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational _ X. private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted government scientific being considered _ X- yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name See continuation sheets street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Cass County Courthouse, Register of Deeds street & number city, town Fargo state North Dakota 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Standing Structures Survey Of Fargo has this property been determined eligible? yes no date Summer 1982 federal state county local depository for survey records State Historical Society of North Dakota, North Dakota Heritage Center city, town Bismarck state North Dakota 7. Description Condition Check one Check one X excellent deteriorated unaltered X original site qood ruins X altered moved date fair f Haii _ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The Fargo, North Dakota, South Residential District begins 4 blocks south of the central business district and 7 to 8 blocks west of the Red River of the North, a natural boun dary separating North Dakota and Minnesota. -

THE NORTH DAKOTA SUPREME COURT: a CENTURY of ADVANCES by Herb Meschke and Ted Smith

1 THE NORTH DAKOTA SUPREME COURT: A CENTURY OF ADVANCES By Herb Meschke and Ted Smith This history was originally published in North Dakota Law Review [Vol. 76:217 (2000)] and is reprinted with permission. The history has been supplemented by Meschke and Smith, A Few More Footnotes for The North Dakota Supreme Court: A Century of Advances, presented to the Judge Bruce M. Van Sickle American Inn of Court (April 26, 2001). Added material in footnotes begins with "+". Links and photographs have been added to the original article. The Appendices contain updated and corrected material. Foreword Lawyers use history, mostly legal precedents, to help guide their clients in their lives and businesses. But not all legal history gets collected and published in appellate opinions, or even in news accounts. History is often scattered in ways that are difficult to follow, and facts are frequently obscured by the fogs of memory. As lawyers, though, we should keep track of the people, politics, and developments that shaped our judicial system, particularly in North Dakota our state Supreme Court. Whether good, bad, or indifferent, the current conditions of the Court and of the judicial system it governs certainly affect how we lawyers practice our profession. Consider these glimpses of how our Court and judicial system came to where they are today. I. LEAVING THE 19TH CENTURY 2 A. The Territorial Courts Before statehood, written appellate review in this region began when the 1861 federal act for Dakota Territory created a three-judge supreme court. President Abraham Lincoln appointed the first three justices of the territorial supreme court: Chief Justice Philemon Bliss of Ohio; George P. -

ABOR and the ~EW Peal: the CASE - - of the ~OS ~NGELES J~~~Y

~ABOR AND THE ~EW pEAL: THE CASE - - OF THE ~OS ~NGELES J~~~y By ISAIAS JAMES MCCAFFERY '\ Bachelor of Arts Missouri Southern State College Joplin, Missouri 1987 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of Oklahoma Siate University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS December, 1989 { Oklahoma ~tate univ •.1...u..1u.Lu..1.; LABOR AND THE NEW DEAL: THE CASE OF THE LOS ANGELES ILGWC Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College 1.i PREFACE This project examines the experience of a single labor union, the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU), in Los Angeles during the New Deal era. Comparisons are drawn between local and national developments within the ILGWU and the American labor movement in general. Surprisingly little effort has been made to test prevailing historical interpretations within specific cities-- especially those lying outside of the industrial northeast. Until more localized research is undertaken, the unique organizational struggles of thousands of working men and women will remain ill-understood. Differences in regional politics, economics, ethnicity, and leadership defy the application of broad-based generalizations. The Los Angeles ILGWU offers an excellent example of a group that did not conform to national trends. While the labor movement experienced remarkable success throughout much of the United States, the Los Angeles garment locals failed to achieve their basic goals. Although eastern clothing workers won every important dispute with owners and bargained from a position of strength, their disunited southern Californian counterparts languished under the counterattacks of business interests. No significant gains in ILGWU membership occurred in Los Angeles after 1933, and the open shop survived well iii into the following decade. -

From the Antebellum Period to the Black Lives Matter Movement 21:512: 391 Fall 2016 Instructor: Dr

Black Thought and the Long Fight for Freedom: From the Antebellum Period to the Black Lives Matter Movement 21:512: 391 Fall 2016 Instructor: Dr. M. Cooper Email: [email protected] Mondays & Wednesdays: 10:00 AM-11:20 AM Room: 348 Conklin Hall Office Hours: Mondays 1:20 PM-2:20 PM; Wednesdays 2:20 PM-3:20 PM, 353 Conklin Hall Course Description This undergraduate seminar examines a diverse group of black intellectuals' formulations of ideologies and theories relative to racial, economic and gender oppression within the context of dominant intellectual trends. The intellectuals featured in the course each contributed to the evolution of black political thought, and posited social criticisms designed to undermine racial and gender oppression, and labor exploitation around the world. This group of black intellectuals' work will be analyzed paying close attention to the way that each intellectual inverts dominant intellectual trends, and/or uses emerging social scientific disciplines, and/or technologies to counter racism, sexism, and classism. This seminar is designed to facilitate an understanding of the black intellectual tradition that has emerged as a result of African American thinkers’ attempts to develop a response to, and understanding of, the black condition. This course explores of a wide range of primary and secondary sources from several different periods, offering students opportunity to explore the lives and works some of the most important black intellectuals. We will also consider the way that period-specific intellectual phenomenon—such as Modernism, Marxism, Pan-Africanism and Feminism— combined with a host of social realities to shape and reshape black thought. -

Cross-Border Ties Among Protest Movements the Great Plains Connection

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Spring 1997 Cross-Border Ties Among Protest Movements The Great Plains Connection Mildred A. Schwartz University of Illinois at Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Schwartz, Mildred A., "Cross-Border Ties Among Protest Movements The Great Plains Connection" (1997). Great Plains Quarterly. 1943. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1943 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. CROSS .. BORDER TIES AMONG PROTEST MOVEMENTS THE GREAT PLAINS CONNECTION MILDRED A. SCHWARTZ This paper examines the connections among supporters willing to take risks. Thus I hypoth political protest movements in twentieth cen esize that protest movements, free from con tury western Canada and the United States. straints of institutionalization, can readily cross Protest movements are social movements and national boundaries. related organizations, including political pro Contacts between protest movements in test parties, with the objective of deliberately Canada and the United States also stem from changing government programs and policies. similarities between the two countries. Shared Those changes may also entail altering the geography, a British heritage, democratic prac composition of the government or even its tices, and a multi-ethnic population often give form. Social movements involve collective rise to similar problems. l Similarities in the efforts to bring about change in ways that avoid northern tier of the United States to the ad or reject established belief systems or organiza joining sections of Canada's western provinces tions. -

![Religious Cult of Father Divine]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4709/religious-cult-of-father-divine-394709.webp)

Religious Cult of Father Divine]

Library of Congress [Religious Cult of Father Divine] [FRANK BYRD RELIGIOUS CULT FATHER DEVINE NY?] DUPLICATE N0. [1500?] DUPLICATE No-1 Dup [As Told To The Writer By The?] [CHIEF OF POLICE SAYVILLE, LONG ISLAND.?] Major T. (Father) Divine has become almost a legendary figure in lower Long Island where he first set up his cult headquarters. Many stories about his peculiar religious doings and subsequent tiffs with the law are told by native inhabitants. The following is only one of many. The writer has taken the liberty of changing names of persons and [?] places. The changes as they appear in the story: [??????????????] Major T. (Father) Divine to Rev. Andrew Elijah Jones. Police Chief Tucker to Chief Becker. Macon Street to Pudding Hill Road. Sayville to Hopeville. Mineola to Salt Point. Judge Smith to Judge Walker. x x x check on New Yorker June 13, 20, 27, 1936 “PEACE IN THE KINGDOM.” [Religious Cult of Father Divine] http://www.loc.gov/resource/wpalh2.21011607 Library of Congress When they first came to town nobody paid much attention to them. They were “ just another group of [Negroes] “ Niggers who had moved in. They were a little different from the others though. Instead of gallivanting all [?] the country-side at night, drinking [?] made [?] and doing [?] [?]-[?] until almost dawn, they worked hard in the white folks' kitchens all day and, as seen as night came, hurriedly finished up with their pots and pans and made a bee-line for Andrew Elijah Jones' little meeting house in the back of Joe Korsak's grocery store. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 19-524 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ROQUE DE LA FUENTE, AKA ROCKY, Petitioner, v. AlEX PADIllA, CALIFOrnIA SECRETARY OF STATE, et al., Respondents. ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES CouRT OF AppEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRcuIT BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE PROFESSORS OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND HISTORY IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER ALICia I. DEARN, ESQ. Counsel of Record 231 South Bemiston Avenue, Suite 850 Clayton, MO 63105 (314) 526-0040 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae 292830 A (800) 274-3321 • (800) 359-6859 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS..........................i TABLE OF CITED AUTHORITIES .............. ii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ..................1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................6 ARGUMENT....................................7 I. CERTIORARI IS DESIRABLE BECAUSE THERE IS CONFUSION AMONG LOWER COURTS OVER WHETHER THE APPLY THE USAGE TEST ...........7 II. THE NINTH CIRCUIT ERRONEOUSLY STATED THAT BECAUSE MINOR PARTY PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES HAVE APPEARED ON THE CALIFORNIA BALLOT, THEREFORE IT IS NOT SIGNIFICANT THAT NO INDEPENDENT PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE HAS QUALIFIED SINCE 1992 ..............................15 CONCLUSION .................................20 ii TABLE OF CITED AUTHORITIES Page CASES: American Party v. Jernigan, 424 F.Supp. 943 (e.d. Ark. 1977)..................8 Arutunoff v. Oklahoma State Election Board, 687 F.2d 1375 (1982)...........................14 Bergland v. Harris, 767 F.2d 1551 (1985) ..........................8-9 Bradley v Mandel, 449 F. Supp. 983 (1978) ........................10 Citizens to Establish a Reform Party in Arkansas v. Priest, 970 F. Supp. 690 (e.d. Ark. 1996) .................8 Coffield v. Kemp, 599 F.3d 1276 (2010) ...........................12 Cowen v. Raffensperger, 1:17cv-4660 ..................................12 Dart v. -

1783.Zeidler.Family

Title: Zeidler Family Papers Call Number: Mss–1783 Inclusive Dates: 1929 – ongoing Quantity: 9.0 cu. ft. total Location: LM, Sh. 143 (2 cu. ft.) WHN, Sh. J117-J118 (7.0 cu. ft.) Abstract: The Zeidler family was very prominent in Milwaukee politics and the Socialist Party. Carl Frederick Zeidler (1908-1945), a lawyer, served as Assistant City Attorney, and in 1940, he was elected Mayor of Milwaukee, running as a non-partisan. He enlisted in the U.S. Navy Reserve and in August 1942 volunteered for active duty. In late 1942 Carl Zeidler was listed as "missing in action" when the La Salle sank and he was placed on the "died in action" list in October 1945. Frank P. Zeidler served three terms as a Socialist Mayor of the City of Milwaukee (1948-1960). Prior to that he had served as a member of the Board of School Directors of the Milwaukee Public Schools (1941-1948) and as the County Surveyor of Milwaukee County (1938-1940). In addition, he was secretary for the Public Enterprise Committee and since serving as Mayor, he also was director of the state department of resource development for Gov. John Reynolds. Beyond his political career, Frank was a fundraiser, assistant to the dean and instructor for Alverno College, a teacher, a labor arbitrator, and a consultant. Mr. Zeidler was also known as an author and speaker on Milwaukee history. Scope and Content: The collection consists of clippings, articles, speeches, newsletters, flyers and other materials relating to Carl and Frank Zeidler, as well as some limited information on the other members of the Zeidler family.