ABSTRACT the BODY UNDERNEATH: a METHOD of COSTUME DESIGN by Leslie Anne Wise Stamoolis a Survey of Costume Design Texts Currentl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Map: Certificate of Achievement for Costume Design and Technology

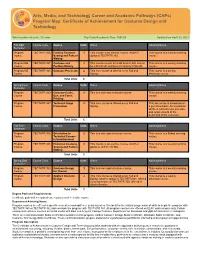

Arts, Media, and Technology Career and Academic Pathways (CAPs) Program Map: Certificate of Achievement for Costume Design and Technology Total number of units: 23 units Top Code/Academic Plan: 1006.00 Updated on April 25, 2021 Fall Odd Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 366 Fantasy Costume 3 This course is an elective course. Another This course is a weekly morning Course Sewing and Pattern option is TECTHTR 365. course. Making Program/GE TECTHTR 367 Costume and 3 This course counts as a GE Area C Arts course This course is a weekly morning Course Fashion History for LACCD GE and Area C1 Arts for CSU GE. course. Program/GE TECTHTR 345 Costume Practicum 2 This core course is offered every Fall and This course is a weekly Course Spring. afternoon course. Total Units 8 Spring Even Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 363 Costume Crafts, 3 This is a core and milestone course. This course is a weekly morning Course Dye, and Fabric course. Printing Program TECTHTR 342 Technical Stage 2 This core course is offered every Fall and This lab course is scheduled on Course Production Spring. a per show basis. An orientation will be held to discuss schedule and requirements at the beginning of the semester. Total Units 5 Fall Even Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 305 Orientation to 2 This is a core and milestone course. This course is a Friday morning Course Technical Careers course. in Entertainment Program TECTHTR 365 Historical Costume 3 This course is an elective course. -

CLOTHING Gown : Áo Đầm Dài Frock

TRANG PHỤC - CLOTHING Gown : áo đầm dài Frock : áo đầm, áo thầy tu Tailcoat : áo đuôi tôm Topcoat : áo bành tô Pallium/pallia : áo bào (của tổng giám mục) Blouse : áo cánh nữ Caftan : áo cáptân (Thổ Nhĩ Kì) Windbreaker : áo chống gió Cassock : áo chùng (tu sĩ) Frock coat : áo choàng Gown : áo choàng (quan tòa; luật sư) Capote : áo choàng dài (thường có mũ trên đầu) Cloak : áo choàng không tay Pelisse : áo choàng lông (nữ) Roe : áo choàng mặc trong nhà Mantlet/ mantelet : áo choàng ngắn Mackinaw : áo choàng ngắn, dày Dress : áo đầm Vest : áo ghi lê Waistcoat : áo ghi lê Jacket : áo jắc két Parka : áo jắc két dày có mũ 76 Trần Quang Khải, Hồng Bàng, Hải Phòng | 02256.538.538 | 01286.538.538 | www.myenglish.edu.vn | facebook.com/MyEnglishCenter Coat : áo khoác Bolero : áo khoác ngắn của nữ (không có nút, khuy phía trước) Overcoat : áo khoác ngoài Smock : áo khoác ngoài (để làm việc); áo chửa Manteau : áo khoác, áo măng tô Kimono : áo ki mô nô Skivvies : áo lót Undershirt : áo lót Vest : áo lót Chemise : áo lót phụ nữ Cardigan : áo len Surplice : áo lễ Chasuble : áo lễ (tu sĩ) Cope : áo lễ (tu sĩ) Blazer : áo màu (thể thao) Mackintosh : áo mưa Raincoat : áo mưa Waterproof : áo mưa Trench coat : áo mưa (quân đội) Slicker : áo mưa thụng dài Nightshirt : áo ngủ (nam) Jersey : áo nịt len Poncho : áo pôn sô (áo cánh dơi) 76 Trần Quang Khải, Hồng Bàng, Hải Phòng | 02256.538.538 | 01286.538.538 | www.myenglish.edu.vn | facebook.com/MyEnglishCenter T-shirt : áo thun có tay Nightclothes : áo quần ngủ Pyjamas, pajamas : áo quần ngủ (nam) Shirt : áo -

Use and Applications of Draping in Turkey's

USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION DUYGU KOCABA Ş MAY 2010 USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF IZMIR UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS BY DUYGU KOCABA Ş IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENTOF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF DESIGN IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES MAY 2010 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences ...................................................... Prof. Dr. Cengiz Erol Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Design. ...................................................... Prof. Dr. Tevfik Balcıoglu Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adaquate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Design. ...................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen Kipöz Supervisor Examining Committee Members Asst. Prof. Dr. Duygu Ebru Öngen Corsini ..................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Nevbahar Göksel ...................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen Kipöz ...................................................... ii ABSTRACT USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION Kocaba ş, Duygu MDes, Department of Design Studies Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen K İPÖZ May 2010, 157 pages This study includes the investigations of the methodology and applications of draping technique which helps to add creativity and originality with the effects of experimental process during the application. Drapes which have been used in different forms and purposes from past to present are described as an interaction between art and fashion. Drapes which had decorated the sculptures of many sculptors in ancient times and the paintings of many artists in Renaissance period, has been used as draping technique for fashion design with the contributions of Madeleine Vionnet in 20 th century. -

EXPLORING IDENTITY Emilio Sosa L Costume Designer Michael Griffo L

EXPLORING IDENTITY Emilio Sosa l Costume Designer Michael Griffo l Author/Educator ELA, Life Skills, Character Studies Grades l 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 FEATURING EMILIO SOSA • FASHION & BROADWAY COSTUME DESIGNER EXPLORING IDENTITY BACKGROUND ARTIST INSIGHT As a Latino, I’m influenced by the bright colors that’s evident in my Latin culture. I also grew up listening to great Latin music and being surrounded by aunts and uncles in their Sunday best. I can now look back and use those influences in a modern way. I think that style comes from within, not just the clothing you wear. Style doesn’t come with a price tag; it comes from knowing yourself and what works for you. I have a strong belief that hard work and dedication are the keys to success and that talent rises to the top. Any challenges I come across I’ve been able to overcome because of my strong will to succeed. My advice to anyone who aspires to work on Broadway or in the fashion field is to gain as much knowledge as possible. Whether it’s through formal education or internships knowledge is power. —Emilio Sosa, Fashion and theatrical costumer designer ABOUT THE EXPERTS SPECIAL GUEST: Emilio Sosa is a first-generation immigrant from the Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, and a graduate of the Pratt Institute. He discovered his passion for design when he was 14 years old and has since achieved his goal of becoming an award- winning fashion and costume designer. In 2006 he was the recipient of the TDF’s Irene Sharaff Young Master Award and named Design Virtuoso by American Theatre Magazine in 2003. -

I Was Tempted by a Pretty Coloured Muslin

“I was tempted by a pretty y y coloured muslin”: Jane Austen and the Art of Being Fashionable MARY HAFNER-LANEY Mary Hafner-Laney is an historic costumer. Using her thirty-plus years of trial-and-error experience, she has given presentations and workshops on how women of the past dressed to historical societies, literary groups, and costuming and re-enactment organizations. She is retired from the State of Washington . E E plucked that first leaf o ff the fig tree in the Garden of Eden and decided green was her color, women of all times and all places have been interested in fashion and in being fashionable. Jane Austen herself wrote , “I beleive Finery must have it” (23 September 1813) , and in Northanger Abbey we read that Mrs. Allen cannot begin to enjoy the delights of Bath until she “was provided with a dress of the newest fashion” (20). Whether a woman was like Jane and “so tired & ashamed of half my present stock that I even blush at the sight of the wardrobe which contains them ” (25 December 1798) or like the two Miss Beauforts in Sanditon , who required “six new Dresses each for a three days visit” (Minor Works 421), dress was a problem to be solved. There were no big-name designers with models to show o ff their creations. There was no Project Runway . There were no department stores or clothing empori - ums where one could browse for and purchase garments of the latest fashion. How did a woman achieve a stylish appearance? Just as we have Vogue , Elle and In Style magazines to keep us up to date on the most current styles, women of the Regency era had The Ladies Magazine , La Belle Assemblée , Le Beau Monde , The Gallery of Fashion , and a host of other publications (Decker) . -

Chapter 3 Methodology…

Chapter 3 Methodology… Methodology….. CHAPTER III METHODOLOGY The research being descriptive and analytical in nature, a longitudinal research design was planned to accomplish the framed objectives. The study had been divided into three different phases. The detailed historical research was conducted during the first phase while the second phase included the collection and documentation of the data. Earnest efforts for the preservation and popularization of the traditional royal costumes were made during the third phase of research. The organized research procedure that would be accomplishing the present study is mentioned as follows: 3.1 Selection of topic The present research had started with an inspiring thought of investigator’s master’s dissertation work and experiences. The researcher had seen various researches and documentation of Indian royal costumes especially of princely states of Rajasthan and Gujarat and found that the dearth of information was available on the royal costumes of Kachchh which led researcher towards its investigation. The present research had taken its shape as a researcher came across royal heritage of Kachchh for taking it into the limelight and preserving it in a decent manner for future generation. Moreover, the statement of the problem identified as Documentation of traditional costumes of rulers of Kachchh. The rulers of Kachchh were not as popular as other princely state rulers. The word “royal costume” provides an impression of luxurious fabrics, embellishments, and royalty. There could be the difference in these elements in royal costumes of Kachchh compared to other ruler’s costume. Kachchh’s geographical location has Rajasthan one end and Sindh Pakistan at the other end as neighboring states which could have influenced the costumes. -

GRAPHIC DESIGNER [email protected] +1(347)636.6681 AWARDS + HONORS SKILLS ASHLEY LAW EDUCATION WORK EXPERIENCE UNIQLO GLOBAL

ASHLEY LAW GRAPHIC DESIGNER [email protected] http://ashleylaw.info +1(347)636.6681 linkedin.com/in/ashley-law instagram.com/_ashleylaw EDUCATION AWA RDS SKILLS SCHOOL OF VISUAL + GRAPHIS (GOLD) SOFTWARE ARTS (New York) NEW TALENT ANNUAL InDesign HONORS BFA Design Editorial Design “Zine”- Illustrator 2017–2019 2018 Photoshop PremierePro AfterEffects SCHOOL OF THE SVA HONOR’S LIST Sketch ART INSTITUTE OF 2017–2018 CHICAGO (Chicago) Fine Art + Visual CAPABILITIES & Critical Studies SAIC MERIT Branding 2013–2015 SCHOLARSHIP Content Production 2013–2015 Identity System Interactive/Digital Design Print + Editorial Design Typography WORK EXPERIENCE UNIQLO GLOBAL Junior Graphic Design for the GCL team focusing on CREATIVE LAB Designer creative direction of special projects, 06. 2019 - Present (New York) under the direction of Shu Hung and John Jay. Campaigns include collaborations (i.e. Lemaire, JW Anderson, Alexander Wang) and new store openings. MATTE PROJECTS Design Intern Designing client proposals, print, 01. 2019–04. 2019 (New York) digital & social collateral for marketing agency. Worked on projects for Cartier, The Chainsmokers, Moda Operandi & MATTE events (FNT, BLACK-NYC, Full Moon Festival, La Luna). PYT OPERANDI Creative Project Associate for artist management & creative 03–06. 2016 Associate project development company with emphasis (Hong Kong) in film, photography, exhibitions, project & business development consulting. CLOVER GROUP Intimates Design Designed for leading global manufacturer INTL LIMITED. Intern of intimate apparel, emphasis on the 08–10. 2015 (Hong Kong) Victoria’s Secret account. Visually detailed creative direction, identity & design of project pitches. Similar work for clients including Wacoal, Aerie, Lane Bryant. GIORGIO ARMANI Menswear R&D Shadowed Manager of R&D department OPERATIONS Intern for Menswear at HK Armani Corporate 06–09. -

Costume Design ©2019 Educational Theatre Association

For internal use only Costume Design ©2019 Educational Theatre Association. All rights reserved. Student(s): School: Selection: Troupe: 4 | Superior 3 | Excellent 2 | Good 1 | Fair SKILLS Above standard At standard Near standard Aspiring to standard SCORE Job Understanding Articulates a broad Articulates an Articulates a partial Articulates little and Interview understanding of the understanding of the understanding of the understanding of the Articulation of the costume costume designer’s role costume designer’s role costume designer’s role costume designer’s role designer’s role and specific and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; job responsibilities; thoroughly presents adequately presents and inconsistently presents does not explain an presentation and and explains the explains the executed and explains the executed executed design, creative explanation of the executed executed design, creative design, creative decisions, design, creative decisions decisions or collaborative design, creative decisions, decisions, and and collaborative process. and/or collaborative process. and collaborative process. collaborative process. process. Comment: Design, Research, A well-conceived set of Costume designs, Incomplete costume The costume designs, and Analysis costume designs, research, and script designs, research, and research, and analysis Design, research and detailed research, and analysis address the script analysis of the script do not analysis addresses the thorough script artistic and practical somewhat address the address the artistic and artistic and practical needs analysis clearly address needs of the production artistic and practical practical needs of the (given circumstances) of the artistic and practical and support the unifying needs of the production production or support the the script to support the needs of production and concept. -

Fashion,Costume,And Culture

FCC_TP_V4_930 3/5/04 3:59 PM Page 1 Fashion, Costume, and Culture Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages FCC_TP_V4_930 3/5/04 3:59 PM Page 3 Fashion, Costume, and Culture Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages Volume 4: Modern World Part I: 19004 – 1945 SARA PENDERGAST AND TOM PENDERGAST SARAH HERMSEN, Project Editor Fashion, Costume, and Culture: Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages Sara Pendergast and Tom Pendergast Project Editor Imaging and Multimedia Composition Sarah Hermsen Dean Dauphinais, Dave Oblender Evi Seoud Editorial Product Design Manufacturing Lawrence W. Baker Kate Scheible Rita Wimberley Permissions Shalice Shah-Caldwell, Ann Taylor ©2004 by U•X•L. U•X•L is an imprint of For permission to use material from Picture Archive/CORBIS, the Library of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of this product, submit your request via Congress, AP/Wide World Photos; large Thomson Learning, Inc. the Web at http://www.gale-edit.com/ photo, Public Domain. Volume 4, from permissions, or you may download our top to bottom, © Austrian Archives/ U•X•L® is a registered trademark used Permissions Request form and submit CORBIS, AP/Wide World Photos, © Kelly herein under license. Thomson your request by fax or mail to: A. Quin; large photo, AP/Wide World Learning™ is a trademark used herein Permissions Department Photos. Volume 5, from top to bottom, under license. The Gale Group, Inc. Susan D. Rock, AP/Wide World Photos, 27500 Drake Rd. © Ken Settle; large photo, AP/Wide For more information, contact: Farmington Hills, MI 48331-3535 World Photos. -

Costume Designer Costume Designer

COSTUME DESIGNER A Costume Designer creates the clothes and costumes for theatre, film, dance, concerts, television and other types of stage productions. The role of the Costume Designer in the professional theatre industry is to design garments and accessories for actors to wear in a production. In this industry the majority of designers, specialise in both set and costume design, although they often have a particular strength in one or the other. READING THE SCRIPT The first step is to read this script, which can give direction as to what the characters are wearing. The script also gives an indication through the character’s personality and behaviour. The designer should consider the time period, the location, as well as the social status of each character. The designer would then liaise with the director to determine the time period and location (as they may change this from the script) and if there is any other style or element they want to achieve. It is imperative that the costume and set design have a cohesive look. BUDGET As a designer you will need to know your budget as this has a big impact upon the design of a production. It is cheaper to produce a contemporary show, so you can op shop costumes or buy them from a retail outlet. Often actors will provide bits and pieces from their own wardrobe on smaller budget shows. Period shows are expensive as most costumes will need to be made. These costs include fabric and trims and employing people to draft patterns, cut and sew them, all of which are labour and time intensive. -

C U R R I C U L U M G U I

C U R R I C U L U M G U I D E NOV. 20, 2018–MARCH 3, 2019 GRADES 9 – 12 Inside cover: From left to right: Jenny Beavan design for Drew Barrymore in Ever After, 1998; Costume design by Jenny Beavan for Anjelica Huston in Ever After, 1998. See pages 14–15 for image credits. ABOUT THE EXHIBITION SCAD FASH Museum of Fashion + Film presents Cinematic The garments in this exhibition come from the more than Couture, an exhibition focusing on the art of costume 100,000 costumes and accessories created by the British design through the lens of movies and popular culture. costumer Cosprop. Founded in 1965 by award-winning More than 50 costumes created by the world-renowned costume designer John Bright, the company specializes London firm Cosprop deliver an intimate look at garments in costumes for film, television and theater, and employs a and millinery that set the scene, provide personality to staff of 40 experts in designing, tailoring, cutting, fitting, characters and establish authenticity in period pictures. millinery, jewelry-making and repair, dyeing and printing. Cosprop maintains an extensive library of original garments The films represented in the exhibition depict five centuries used as source material, ensuring that all productions are of history, drama, comedy and adventure through period historically accurate. costumes worn by stars such as Meryl Streep, Colin Firth, Drew Barrymore, Keira Knightley, Nicole Kidman and Kate Since 1987, when the Academy Award for Best Costume Winslet. Cinematic Couture showcases costumes from 24 Design was awarded to Bright and fellow costume designer acclaimed motion pictures, including Academy Award winners Jenny Beavan for A Room with a View, the company has and nominees Titanic, Sense and Sensibility, Out of Africa, The supplied costumes for 61 nominated films. -

Theatre (THEA)

Kent State University Catalog 2021-2022 1 THEA 11724 FUNDAMENTALS OF PRODUCTION LABORATORY II: THEATRE (THEA) PROPS AND SCENIC ART 1 Credit Hour Practice in theatre production techniques in the area of properties and THEA 11000 THE ART OF THE THEATRE (DIVG) (KFA) 3 Credit Hours scenic art. Using the life-centered nature of theatre as a medium of analysis, this Prerequisite: Special approval. course is designed to develop critically engaged audience members Corequisite: THEA 11722. who are aware of the impact, significance and historical relevance of the Schedule Type: Laboratory interconnection between culture and theatre performance. Contact Hours: 2 lab Prerequisite: None. Grade Mode: Standard Letter Schedule Type: Lecture Attributes: CTAG Performing Arts, TAG Arts and Humanities Contact Hours: 3 lecture THEA 11732 FUNDAMENTALS OF PRODUCTION II: COSTUMES, Grade Mode: Standard Letter LIGHTING AND PROJECTIONS 2 Credit Hours Attributes: Diversity Global, Kent Core Fine Arts, Transfer Module Fine An introduction to professional theatre production principles and Arts practices in the areas of costumes, lighting and projections. THEA 11100 MAKING THEATRE: CULTURE AND PRACTICE 2 Credit Prerequisite: Special approval. Hours Schedule Type: Lecture Overview of theatre practices through creative experiential learning. The Contact Hours: 2 lecture focus and course content combines practical and cultural experiences Grade Mode: Standard Letter and culminates with a performance event that provides a solid foundation Attributes: CTAG Performing Arts in the artistic process and an identity for the first-year theatre student. THEA 11733 FUNDAMENTALS OF PRODUCTION LABORATORY III: Prerequisite: Special approval. COSTUMES 1 Credit Hour Schedule Type: Lecture Practice in theatre production techniques in the area of costumes.