Lynn, 2007, Human-Animal Studies, EHAR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What's the Difference Between the B.A. and B.S. Degree In

What’s the Difference Between the B.A. and B.S. Degree in ES? 8.1.20 If you’re thinking about pursuing Environmental Studies (ES) at UC Santa Barbara the first important decision you have to make is choosing which degree to pursue, the Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) or Bachelor of Science (B.S.) in Environmental Studies. While both majors are similar in design and stress the importance of understanding the complex interrelationships between the humanities, social sciences, and natural science disciplines, having two degree options allows students maximum flexibility to choose a major that best fits their environmental interests and goals. In this document we provide a detailed comparison of the academic requirements of the B.A. and B.S. major so one can understand the differences and can make an educated decision. Given your decision will also be based on what you want to do after graduation we thought it might be helpful to also highlight just a few example career paths each degree might lead to. Just remember, no matter which major you choose, your decision should be based on what you believe will ultimately make you happy. Simply put, the B.A. degree in ES is the more interdisciplinary major, requiring a swath of introductory courses in the humanities, social, physical, and natural sciences. It stresses the importance of comprehending basic social, cultural, and scientific theories and understanding how they interact with one another and play an important part of every environmental issue. While this degree will make one science literate, the degree offers maximum flexibility to select ES electives and outside concentration courses from just about every academic discipline at UCSB, including: arts, policy, culture, languages, humanities, and economics to name just a few. -

Postgraduate/Distance Learning Assignment Coversheet & Feedback Form

Postgraduate/Distance Learning Assignment coversheet & feedback form THIS SHEET MUST BE THE FIRST PAGE OF THE ASSIGNMENT YOU ARE SUBMITTING (DO NOT SEND AS A SEPARATE FILE) For completion by the student: Student Name: SAMANTHA JANE HOLLAND Student University Email: [email protected] Module code: Student ID number: Educational support needs: 1001693 Yes/No Module title: DISSERTATION Assignment title: OTHAs AND ENVIRONMENT IN ANIMAL ETHICS AND ENVIRONMENTAL PHILOSOPHY: ONTOLOGY AND ETHICAL MOTIVATION BEYOND THE DICHOTOMIES OF ANTHROPOCENTRISM Assignment due date: 2 April 2013 This assignment is for the 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th module of the degree N/A Word count: 22,000 WORDS I confirm that this is my original work and that I have adhered to the University policy on plagiarism. Signed …………………………………………………………… Assignment Mark 1st Marker’s Provisional mark 2nd Marker’s/Moderator’s provisional mark External Examiner’s mark (if relevant) Final Mark NB. All marks are provisional until confirmed by the Final Examination Board. For completion by Marker 1 : Comments: Marker’s signature: Date: For completion by Marker 2/Moderator: Comments: Marker’s Signature: Date: External Examiner’s comments (if relevant) External Examiner’s Signature: Date: ii OTHAs AND ENVIRONMENT IN ANIMAL ETHICS AND ENVIRONMENTAL PHILOSOPHY: ONTOLOGY AND ETHICAL MOTIVATION BEYOND THE DICHOTOMIES OF ANTHROPOCENTRISM Samantha Jane Holland March 2013 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA Nature University of Wales, Trinity Saint David Master’s Degrees by Examination and Dissertation Declaration Form. 1. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. -

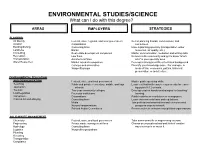

ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES/SCIENCE What Can I Do with This Degree?

ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES/SCIENCE What can I do with this degree? AREAS EMPLOYERS STRATEGIES PLANNING Air Quality Federal, state, regional, and local government Get on planning boards, commissions, and Aviation Corporations committees. Building/Zoning Consulting firms Have a planning specialty (transportation, water Land-Use Banks resources, air quality, etc.). Consulting Real estate development companies Master communication, mediation and writing skills. Recreation Law firms Network in the community and get to know "who's Transportation Architectural firms who" in your specialty area. Water Resources Market research companies Develop a strong scientific or technical background. Colleges and universities Diversify your knowledge base. For example, in Nonprofit groups areas of law, economics, politics, historical preservation, or architecture. ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION AND COMMUNICATION Federal, state, and local government Master public speaking skills. Teaching Public and private elementary, middle, and high Learn certification/licensure requirements for teach- Journalism schools ing public K-12 schools. Tourism Two-year community colleges Develop creative hands-on strategies for teaching/ Law Regulation Four-year institutions learning. Compliance Corporations Publish articles in newsletters or newspapers. Political Action/Lobbying Consulting firms Learn environmental laws and regulations. Media Join professional associations and environmental Nonprofit organizations groups as ways to network. Political Action Committees Become active in environmental -

Environmental Studies (CASNR) 1

Environmental Studies (CASNR) 1 ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES College Requirements College Admission (CASNR) Requirements for admission into the College of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources (CASNR) are consistent with general University Description admission requirements (one unit equals one high school year): 4 units of English, 4 units of mathematics, 3 units of natural sciences, 3 units Website: esp.unl.edu (http://esp.unl.edu/) of social sciences, and 2 units of world language. Students must also The environmental studies major is designed for students who want to meet performance requirements: a 3.0 cumulative high school grade make a difference and contribute to solving environmental challenges point average OR an ACT composite of 20 or higher, writing portion not on a local to global scale. Solutions to challenges such as climate required OR a score of 1040 or higher on the SAT Critical Reading and change, pollution, and resource conservation require individuals who Math sections OR rank in the top one-half of graduating class; transfer have a broad-based knowledge in the natural and social sciences, as students must have a 2.0 (on a 4.0 scale) cumulative grade point average well as strength in a specific discipline. The environmental studies and 2.0 on the most recent term of attendance. For students entering major will provide the knowledge and skills needed for students to the PGA Golf Management degree program, a certified golf handicap work across disciplines and to be competitive in the job market. The of 12 or better (e.g., USGA handicap card) or written ability (MS Word environmental studies program uses a holistic approach and a framework file) equivalent to a 12 or better handicap by a PGA professional or high of sustainability. -

Giving Voice to the "Voiceless:" Incorporating Nonhuman Animal Perspectives As Journalistic Sources

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Faculty Publications Department of Communication 2011 Giving Voice to the "Voiceless:" Incorporating Nonhuman Animal Perspectives as Journalistic Sources Carrie Packwood Freeman Georgia State University, [email protected] Marc Bekoff Sarah M. Bexell [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_facpub Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Recommended Citation Freeman, C. P., Bekoff, M. & Bexell, S. (2011). Giving voice to the voiceless: Incorporating nonhuman animal perspectives as journalistic sources. Journalism Studies, 12(5), 590-607. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOICE TO THE VOICELESS 1 A similar version of this paper was later published as: Freeman, C. P., Bekoff, M. & Bexell, S. (2011). Giving Voice to the Voiceless: Incorporating Nonhuman Animal Perspectives as Journalistic Sources, Journalism Studies, 12(5), 590-607. GIVING VOICE TO THE "VOICELESS": Incorporating nonhuman animal perspectives as journalistic sources Carrie Packwood Freeman, Marc Bekoff and Sarah M. Bexell As part of journalism’s commitment to truth and justice -

All Creation Groans: the Lives of Factory Farm Animals in the United States

InSight: RIVIER ACADEMIC JOURNAL, VOLUME 13, NUMBER 1, SPRING 2017 “ALL CREATION GROANS”: The Lives of Factory Farm Animals in the United States Sr. Lucille C. Thibodeau, pm, Ph.D.* Writer-in-Residence, Department of English, Rivier University Today, more animals suffer at human hands than at any other time in history. It is therefore not surprising that an intense and controversial debate is taking place over the status of the 60+ billion animals raised and slaughtered for food worldwide every year. To keep up with the high demand for meat, industrialized nations employ modern processes generally referred to as “factory farming.” This article focuses on factory farming in the United States because the United States inaugurated this approach to farming, because factory farming is more highly sophisticated here than elsewhere, and because the government agency overseeing it, the Department of Agriculture (USDA), publishes abundant readily available statistics that reveal the astonishing scale of factory farming in this country.1 The debate over factory farming is often “complicated and contentious,”2 with the deepest point of contention arising over the nature, degree, and duration of suffering food animals undergo. “In their numbers and in the duration and depth of the cruelty inflicted upon them,” writes Allan Kornberg, M.D., former Executive Director of Farm Sanctuary in a 2012 Farm Sanctuary brochure, “factory-farm animals are the most widely abused and most suffering of all creatures on our planet.” Raising the specter of animal suffering inevitably raises the question of animal consciousness and sentience. Jeremy Bentham, the 18th-century founder of utilitarianism, focused on sentience as the source of animals’ entitlement to equal consideration of interests. -

MAC1 Abstracts – Oral Presentations

Oral Presentation Abstracts OP001 Rights, Interests and Moral Standing: a critical examination of dialogue between Regan and Frey. Rebekah Humphreys Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom This paper aims to assess R. G. Frey’s analysis of Leonard Nelson’s argument (that links interests to rights). Frey argues that claims that animals have rights or interests have not been established. Frey’s contentions that animals have not been shown to have rights nor interests will be discussed in turn, but the main focus will be on Frey’s claim that animals have not been shown to have interests. One way Frey analyses this latter claim is by considering H. J. McCloskey’s denial of the claim and Tom Regan’s criticism of this denial. While Frey’s position on animal interests does not depend on McCloskey’s views, he believes that a consideration of McCloskey’s views will reveal that Nelson’s argument (linking interests to rights) has not been established as sound. My discussion (of Frey’s scrutiny of Nelson’s argument) will centre only on the dialogue between Regan and Frey in respect of McCloskey’s argument. OP002 Can Special Relations Ground the Privileged Moral Status of Humans Over Animals? Robert Jones California State University, Chico, United States Much contemporary philosophical work regarding the moral considerability of nonhuman animals involves the search for some set of characteristics or properties that nonhuman animals possess sufficient for their robust membership in the sphere of things morally considerable. The most common strategy has been to identify some set of properties intrinsic to the animals themselves. -

The Us Egg Industry – Not All It's Cracked up to Be for the Welfare Of

File: 10.03 drake JBN Macro Final.doc Created on: 4/24/2006 9:38:00 PM Last Printed: 5/8/2006 10:51:00 AM THE U.S. EGG INDUSTRY – NOT ALL IT’S CRACKED UP TO BE FOR THE WELFARE OF THE LAYING HEN: A COMPARATIVE LOOK AT UNITED STATES AND EUROPEAN UNION WELFARE LAWS Jessica Braunschweig-Norris I. Chickens Used for Food and Food Production in the United States Egg Industry: An Overview................................513 II. The Implications for Laying Hens: Plight and Protection...................515 A. Cage Systems.................................................................................515 1. The United States Cage System..............................................517 2. The EU Standards: Out with the Old, In with the New..........518 a. Unenriched Cage Systems: The End of the Traditional Battery Cage..........................518 b. Enriched Cages ................................................................519 c. Alternative Systems: The Free Range or Cage-Free System..............................520 B. Beak Trimming.............................................................................520 C. Forced Molting .............................................................................522 D. Transportation and Slaughter........................................................523 III. The Disparity: United States Welfare Law and Policy and the EU’s Progressive Legislative Vision.......................................525 A. The United States Law & Policy: Falling Behind .......................526 1. Non-Existent Federal Protection -

The Scope of the Argument from Species Overlap

bs_bs_banner Journal of Applied Philosophy,Vol.31, No. 2, 2014 doi: 10.1111/japp.12051 The Scope of the Argument from Species Overlap OSCAR HORTA ABSTRACT The argument from species overlap has been widely used in the literature on animal ethics and speciesism. However, there has been much confusion regarding what the argument proves and what it does not prove, and regarding the views it challenges.This article intends to clarify these confusions, and to show that the name most often used for this argument (‘the argument from marginal cases’) reflects and reinforces these misunderstandings.The article claims that the argument questions not only those defences of anthropocentrism that appeal to capacities believed to be typically human, but also those that appeal to special relations between humans. This means the scope of the argument is far wider than has been thought thus far. Finally, the article claims that, even if the argument cannot prove by itself that we should not disregard the interests of nonhuman animals, it provides us with strong reasons to do so, since the argument does prove that no defence of anthropocentrism appealing to non-definitional and testable criteria succeeds. 1. Introduction The argument from species overlap, which has also been called — misleadingly, I will argue — the argument from marginal cases, points out that the criteria that are com- monly used to deprive nonhuman animals of moral consideration fail to draw a line between human beings and other sentient animals, since there are also humans who fail to satisfy them.1 This argument has been widely used in the literature on animal ethics for two purposes. -

PHIL 221 – Ethical Theory (3 Credits) Course Description

PHIL 221 – Ethical Theory (3 credits) Course Description: This course focuses on theories of morality rather than on contemporary moral issues (that is the topic of PHIL 120). That means that we will primarily be preoccupied with exploring what it means for an action—or a person—to be “good”. We will attempt to answer this question by looking at a mix of historical and contemporary texts primarily drawn from the Western European tradition, but also including some works from China and pre-colonial central America. We will begin by asking whether there are any universal and objectively valid moral rules, and chart several attempts to answer in both the affirmative and the negative: relativism, egoism, virtue ethics, consequentialism, deontology, the ethics of care, and contractarianism. We will consider the relationship between morality and the law, and whether morality is linked to human happiness. Finally, we will consider arguments for and against the idea that moral facts actually exist. Schedule of Readings Week 1 Introduction What are we trying to do? Charles L. Stevenson – The Nature of Ethical Disagreement Tom Regan – How Not to Answer Moral Questions Week 2 Relativism What counts as good depends on the moral standards of the group doing the evaluating. Mary Midgley – Trying Out One’s New Sword Martha Nussbaum – Judging Other Cultures: The Case of Genital Mutilation Plato – The Myth of Gyges (Republic II) Week 3 Egoism What’s good is just what’s good for me. Mencius – Mengzi (excerpts) James Rachels – Egoism and Moral Skepticism Week 4 Virtue Ethics Morality depends on having a virtuous character. -

Environmental Studies Is Not for Turer, and Carol Goody As Our ES Our ES Students and Enhance the the Faint of Heart

Volume 1, Issue 1 Greetings from the Director 2007-2008 Being a faculty member or student Program Coordinator and Lec- valuable learning opportunities for in environmental studies is not for turer, and Carol Goody as our ES our ES students and enhance the the faint of heart. As a global Administrative Assistant. environmental understanding of all Skidmore students as they live and population, we face seemingly As was the case in 2002 when we learn on a more environmentally- insurmountable environmental first implemented the ES major, friendly campus. issues – climate change, water Skidmore students continue to be pollution, air pollution, loss of the driving force in ES. While we In addition to our strides on cam- biodiversity, compromised agricul- began the ES major with one pus, we have strengthened bridges tural productivity, and more. I’m graduate in 2002 (Jenna Ringel- with the surrounding community often asked how I remain positive heim, see page 2), our declared through the Water Resources Ini- while absorbed in such daunting majors and minors now number tiative (see insert) and our en- challenges on a day to day basis. It over sixty. Our ES students’ ac- hanced efforts on internship place- certainly helps that I have a stereo- complishments during their time at ments. Our community partners typical Midwestern disposition; I Skidmore (see page 3) and in their provide valuable learning opportu- fall firmly at the friendly end of post-Skidmore life (page 4) are nities for students and faculty alike the personality spectrum, I tend to nothing short of remarkable. Most and are just as much a part of our view the world through a rosy set rewarding for me, however, is the ES Program as our campus con- of lenses, and yes, I am a bit ob- willingness of our current students stituents. -

Review Of" Science and Poetry" by M. Midgley

Swarthmore College Works Philosophy Faculty Works Philosophy 10-1-2003 Review Of "Science And Poetry" By M. Midgley Hans Oberdiek Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-philosophy Part of the Philosophy Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Hans Oberdiek. (2003). "Review Of "Science And Poetry" By M. Midgley". Ethics. Volume 114, Issue 1. 187-189. DOI: 10.1086/376710 https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-philosophy/121 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mary Midgley, Science and Poetry Science and Poetry by Mary. Midgley, Review by: Reviewed by Hans Oberdiek Ethics, Vol. 114, No. 1 (October 2003), pp. 187-189 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/376710 . Accessed: 09/06/2015 16:15 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Ethics.