With Compliments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Teaching TRANSLATED from KASHTI-NUH

Our Teaching TRANSLATED FROM KASHTI-NUH by HAZRAT MIRZA GHULAM AHMAD Promised Messiah & Mahdi Founder of the Ahmadiyya Movement in Islam Published by: Nazarat Nashro Ishaat Sadr Anjuman Ahmadiyya Qadian - 143516 Distt. Gurdaspur (Punjab) Our Teaching (English Translation of a portion of the urdu Book KISHTI-E-NUH) Written by : Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Promised Messiah & Mehdi Founder of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat First Published in 1988 Previous Edition 2010 Present Edition 2016 Copies 2000 Published by : Nazarat Nashr-o-Ishaat Sadr Anjuman Ahmadiyya Qadian - 143516 Distt. Gurdaspur (Pb.) INDIA Printed at : Fazl-e-Umar Printing Press, Qadian ISBN : 978-81-7912-257-0 FOREWORD This is a time when the darkness of materialism has overspread the entire face of the earth and obscured people’s vision. Many there are who profess faith but are deprived of its true sweetness and strength. They are unaware of the One Living, Omnipresent God. For the benefit of seekers after truth, therefore, I present an abridged version of the teaching of the Holy Founder of the Ahmadiyya Movement as laid down in his book Kashti-Nuh (lit. Noah’s Ark) which he wrote to save men from the current deluge of irreligion and materialism. This book was intended mainly for the members of the Ahmadiyya Community but Muslims in general have also been addressed in it. The book is a torch of guidance through which every Muslim, nay every man with a craving for truth and spirituality, can rekindle his inner lamp and illuminate his heart. The present abridgement is an English rendering of the Founder’s own sacred words and, therefore, is replete with all the blessings that descend from heaven on the heart of a holy person. -

The Light & Islamic Review

"Call to the path of thy Lord with wisdom and goodly exhortation, and argue with people in the best possible manner." (Holy Quran 16:125) The Light & Islamic Review Exponent of Islam and the Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement since 1924. A journal devoted to showing that I slam is: PEACEFUL - TOLERANT - RATIONAL - INSPIRING Vol. 69 JANUARY - FEBRUARY 1992 No. 1 CONTENTS ■ Our Teachings. by Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad . 3 ■ Lessons of the Pilgrimage and 'id al-adhii. address by Dr. Zahid Aziz . 4 ■ Criticism by misrepresentation. Reply to Christian leaflet attacking Islam 7 ■ Islam -The new world order. by K.S. Rahim Bakhsh . 10 ■ Mr. Jinnah regarded Ahmadis as Muslims. His refusal to brand them as non-Muslim 12 ■ Introduction to Islam. 13 ■ Mr. N. A. Faruqui passes away . 15 * Published from: 1315 Kings Gate Road. Columbus, Ohio 43221-1504, U.S.A. www.alahmadiyya.org 2 THE LIGHT • JANUARY - FEBRUARY 1992 The Light was founded in 1924 as the organ of the Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha'at Islam, Lahore, Pakistan (Ahmadiyya Association Our Representatives. for the propagation of Islam, Lahore). The Islamic Review was Canada. published in England from 1913 for over 50 years, and in the Mr. Yaseen Sahu Khan U.S.A. from 1980 to 1991. The present periodical represents the 3181 East 15thAvenue, world-wide Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha'at Islam, Lahore, branches. Vancouver, BC. V5M 2LI ISSN: 1060-4596 Germany. Editor: Dr. Zahid Aziz. Mr.Saeed Ahmad Choudhary, Circulation: Mrs. Samina Sahukhan, Dr. Noman I. Malik. Die Moschee, BriennerStrasse 7/8, D-1000 Berlin-31 Articles, letters and views are welcome, and should be sent to: The Editor, 'The Light', 15 Stanley Avenue, Wembley, Nederland. -

Handbook of Religious Beliefs and Practices

STATE OF WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES 1987 FIRST REVISION 1995 SECOND REVISION 2004 THIRD REVISION 2011 FOURTH REVISION 2012 FIFTH REVISION 2013 HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES INTRODUCTION The Department of Corrections acknowledges the inherent and constitutionally protected rights of incarcerated offenders to believe, express and exercise the religion of their choice. It is our intention that religious programs will promote positive values and moral practices to foster healthy relationships, especially within the families of those under our jurisdiction and within the communities to which they are returning. As a Department, we commit to providing religious as well as cultural opportunities for offenders within available resources, while maintaining facility security, safety, health and orderly operations. The Department will not endorse any religious faith or cultural group, but we will ensure that religious programming is consistent with the provisions of federal and state statutes, and will work hard with the Religious, Cultural and Faith Communities to ensure that the needs of the incarcerated community are fairly met. This desk manual has been prepared for use by chaplains, administrators and other staff of the Washington State Department of Corrections. It is not meant to be an exhaustive study of all religions. It does provide a brief background of most religions having participants housed in Washington prisons. This manual is intended to provide general guidelines, and define practice and procedure for Washington State Department of Corrections institutions. It is intended to be used in conjunction with Department policy. While it does not confer theological expertise, it will, provide correctional workers with the information necessary to respond too many of the religious concerns commonly encountered. -

The Light & Islamic Review

"Call to the path ofthy Lord with wisdom and goodly exhortation, and argue with people in the best possible manner." (The Holy Quran 16:125) The Light published since 1924. Exponent of Islam and the Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement. A journal devoted to showing that Islam is: PEACEFUL - TOLERANT - RATIONAL - INSPIRING Vol. 68 SEPTEMBER - OCTOBER 1991 No. 3 CONTENTS ■ Our Teachings by Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad . 3 ■ Special tribute to Maulana Hafiz SherMohammad by Dr. Zahid Aziz . 4 ■ Introduction to Islam Basic questions answered in simple form 11 ■ Beliefs theof Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement Hazrat Mirza's claims accord with Islam 13 ■ News and Notes . 15 1) Jesus did not die on the cross - View of eminent British physician. 2) About Ourselves - Changes in TheLight . • Published from: 15 Stanley A venue, Wembley, Middlesex, HAO 4JQ. ENGLAND. 1315 Kings Gate Road, Columbus, Ohio 43221, U.S.A. www.alahmadiyya.org 2 THE LIGHT ■ SEPTEMBER - OCTOBER 1991 The Light was founded as the organ of the Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha'at Islam, Lahore, Pakistan (the Ahmadiyya Our Representatives. Association fQrthe propagation of Islam, established at Lahore Canada. in 1914). It is now the international periodical of the world Mr. Yaseen Sahu Khan wide branches of the Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha'at Islam, 3181 East 15th Avenue, Lahore. Vancouver, BC. V5M 2Ll Beliefs and aims. Germany. Mr. Saeed Ahmad Choudhary, The main· object of the A.A.1.1.L. is to present the true, Die Moschee, original message of Islam to the whole world - Islam as it is Brienner Strasse 7/8 , found in the Holy Qur� and the life of the Holy Prophet D-1000 Berlin-31 Muhammad, which is obscured today by grave misconceptions Nederland. -

New Ahmadis Syllabus and Reading Lists

New Ahmadis Syllabus and Reading Lists A guide to Weekly Training Classes Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 1 DUTIES OF THE ADDITIONAL SECRETARY TARBIYYAT AND WAQF-E-JADID NEW AHMADIS 2 RULE 425 & RULE 426 2 DUTY 1 3 ORGANISING WEEKLY LOCAL NEW AHMADI RELIGIOUS TRAINING CLASSES 3 READING LISTS & CORE TEXTS 4 HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE 5 BASICS OF RELIGIOUS EDUCATION 6 CLASS 1- INTRODUCTION TO ISLAM 6 CLASS 2 – SET OF BELIEFS 6 CLASS 3 – ACTS OF WORSHIP 6 CLASS 4 – CODE OF CONDUCT AND PURPOSE OF LIFE 7 CLASS 5 – DISTICTIVE FEATURES OF ISLAM 7 CLASS 6 – AHMADIYYAT, THE REVIVAL OF ISLAM 7 CLASS 7 – ALLAH AND HIS ATTRIBUTES 8 CLASS 8 – THE HOLY QUR’AN AND IT’S ETIQUETTE 8 CLASS 9 – ALPHABETICAL LIST OF SURAHS 8 CLASS 10 – INTRODUCTION TO AHADITH 9 CLASS 11 – FORTY AHADITH WITH COMMENTARY (PART 1) 9 CLASS 12 - FORTY AHADITH WITH COMMENTARY (PART 2) 9 CLASS 13 – FORTY AHADITH WITH COMMENTARY (PART 3) 9 CLASS 14 – FORTY AHADITH WITH COMMENTARY (PART 4) 10 CLASS 15 – FORTY AHADITH WITHOUT COMMENTARY (PART 1) 10 CLASS 16 – FORTY AHADITH WITHOUT COMMENTARY (PART 2) 10 CLASS 17 – FORTY AHADITH WITHOUT COMMENTARY (PART 3) 10 CLASS 18 – FORTY AHADITH WITHOUT COMMENTARY (PART 4) 11 CLASS 19 – IMPORTANCE OF SALAT 11 CLASS 20 – INTRODUCTION TO SALAT (PART 1) 11 CLASS 21 – INTRODUCTION TO SALAT (CONT) 11 CLASS 22 – INTRODUCTION TO SALAT (PART 2) 12 CLASS 23 – SALAT (PART 1) 12 CLASS 24 – SALAT (PART 2) 12 CLASS 25 – OTHER PRAYERS RELATED TO SALAT (PART 1) 12 CLASS 26 – OTHER PRAYERS RELATED TO SALAT (PART 2) 13 CLASS 27 – TABLE OF TRANSLATION AND TRANSLITERATION -

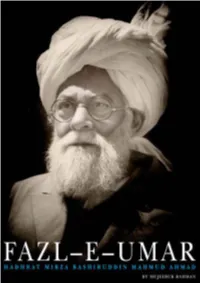

Fazl-E-Umar.Pdf

FAZL-E-UMAR The Life of Hadhrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad Khalifatul Masih II [ra] First published in the UK in 2012 by Islam International Publications Copyright © Majlis Khuddamul Ahmadiyya UK 2012 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. For legal purposes the Copyright Acknowledgements constitute a continuation of this copyright page. ISBN: 978-0-85525-995-2 Designed and distributed by Majlis Khuddamul Ahmadiyya UK Author: Mujeebur Rahman Printed and bound by Polestar UK Print Limited CONTENTS Letter from Hadhrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad [atba] 1 Foreword 3 Comments by Sadr Majlis Khuddamul Ahmadiyya UK 5 Acknowledgements 6 Introduction 9 PART 1 15 Early childhood and parental training 17 Education 41 Public speaking and writing 55 Childhood interests, games and pastimes 63 Circle of contacts 75 Belief in the truth of his father and its consequences 80 Ever–growing faith in the Promised Messiah [as] 88 The death and burial of the Promised Messiah [as] 90 Historic pledge of Hadhrat Sahibzada Mirza Mahmud Ahmad 98 PART 2 103 Establishment of Khilafat in the Ahmadiyya Movement 105 Efforts to support and strengthen the institution of Khilafat 110 PART 3 143 Khilafat of Hadhrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad [ra] 144 Independence -

English Section

An informational, literary, educational, and training magazine of Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, USA January-February 2016 The Ahmadiyya GAZETTE USA Muslih Mau'ud Edition Inauguration Ceremony of the Nusrat Mosque Extremists recruit by distorting Islam. Coon Rapids, Minnesota But we can STOP them. And YOU can help. Behold! a light cometh, a light anointed by God Tabligh Activities in Merida, Mexico with the perfume of His pleasure. We shall pour our spirit into him and he will be sheltered under the shadow of God. He will grow rapidly in stature and will be the means of procuring the release of those held in bond- age. His fame will spread to the ends of the earth and peoples will be blessed through him. Support our CAMPAIGN against EXTREMISTS www.TrueIslam.com WAQFE NAU BOYS’ ANNUAL TRIP TO JAMIA AHMADIYYA, CANADA Register online at www.waqfenau.us APRIL 8 - 10, 2016 (FRI - SUN) Experience a full day at the Jamia along with sports competitions and sightseeing APPLY FOR ADMISSION TO JAMIA AHMADIYYA, CANADA Jamia Ahmadiyya Canada is seeking US applicants for admission into the 7-year Shahid degree program beginning in fall, 2016. The applicants for admission must fulfill the following prerequisites: The applicant must be between 17 and 20 years of age. The applicant must have finished high school. The applicant must apply for Waqfe Zindagi (life dedication) also. The applicant must be able to recite the Holy Quran correctly. For detailed information, please contact [email protected] or call (706)- 860-1629. Hafiz Samiullah Chaudhary National Secretary Waqfe Nau, USA The Ahmadiyya Gazette USA Vol. -

Islam and the Lahore Ahmadiyya Community

From:www.ahmadiyya.org Islam and the Lahore Ahmadiyya Community Address in Committee Room 6 of the House of Commons, London, 19th November 2014 by Dr Abdul Karim Saeed Hazrat Ameer (World-wide Head) of the Lahore Ahmadiyya Community ‘And if your Lord had pleased, all those who are in the earth would have been believers, all of them. Will you (O Prophet) then force people till they are believers?’ — The Holy Quran, 10:99 Members of the honourable Houses of Lords and Commons, and ladies and gentlemen: Firstly, I am thankful thatBritish law and traditions have made it possible for Muslims not only to live in the UK but also practice and preach their faith, Islam, with complete freedom, freedom from discrimination and freedom from harassment. Secondly, my respectful thanks aredue to all the successive Governments of this country for promoting tolerance of various religions, and to the British people for living in peace and harmony with Muslims who are settled here. My first visit to UK was about 40 years back,and it was love at first sight with UK in general and London in particular. Tower Bridge, Big Ben and the Houses of Parliament with the River Thames were a captivating sight. Not in my wildest dreams could I have imagined that one day I would be standing right inside the Houses of Parliament addressing a gathering. It was in London that I qualified as MRCP UK from the Royal College of Physicians and was later honoured by that prestigious institution which granted me its fellowship, FRCP, in recognition of my services to medical education. -

Hilal Judgment on Moon

HHIILLAALL JJUUDDGGMMEENNTT OONN MMOOOONNSSIIGGHHTTIINNGG AACCCCOORRDDIIINNGG TTOO SSHHAARRIIAA’’’HH TTHHEE HHIISSTTOORRYY OOFF AASSTTRROONNOOMMYY AANNDD TTHHEE LLAATTEESSTT RREESSEEAARRCCHH (Including the Fatawa & Opinions of The Ahlus Sunnah wal Jama’ah with Fatawaa of Hanafi Scholars from the Barelwi and Deobandi schools) Author: MMoolllvviii YYaa’’’qquubb AAhhmmaadd MMiiiffttaahhiii Translated By : MMuuffftttiii MMuuhhaammmmaadd AAsslllaamm PPaattteelll : Published by; : Central Moon-sighting Committee of Great Britain Edition 1430/2009 ل ا و : ََٰٰ َ اَِْ َُْا َاُِْْا اَ َوَرَُُْ َو َ ََْا َُْ َوَأﻥُْْ َََُْْن َوَ َُْﻥُْا آََِْ َُْا ََِْ َوهُْ َ َََُْْن ول ا: ََُْْﻥََ َِ اْ َهِِ ُْ هَِ ََاُِْ ِِس َواَْ ِّ ( رة اة ) و ل ا ا و : ا ﺡ وا ال و وا ﺡ و ن روا و روا آا اة ول ا: ﺹا ؤ وا وا ؤ ن ا آا ة ن ول ا : إﻥ أ أ ﻥ و ﻥ ا ها وها وا ها وها ول ا: إن ام ﺏأ ود آ ﺏأ ورز ﺏ ا آ ز ا ه ول ا: ا ا ﺏ وذرا ﺏراع ﺡ دا ﺡ ه , رل ا اد وارى ل ؟ ول ا : َ َاَِْ َُْااِن ُِْْا اِْ آ وا دواآ اﺏ َْا Origin of this Book Origin of this Book: `Shar'i Thuboote Hilal, Tarikhe Falakiyat aur Jadeed Tahqique`` translated by Mufti Muhammed Aslam Patel of Harare , Zimbabwe. My most sincere thanks and appreciation to the efforts by the Translator for his dedicated commitment to completing this translation. May Allaah accept his most sincere intentions. Aameen. There are new sighting data, including international and UK moon sighting records collected by Hizbul Ulema UK. Specifically the sightings by seventeen people (13 from Blackburn in Lancashire and 4 from Batly in Yorkshire); two persons from Birmingham Central Masjid; eight Ulema of Darul Uloom Bury; and three Ulema from Darul Uloom Leicester, England. -

Qualities of a True Ahmadi Muslim

Qualities of a True Ahmadi Muslim AN INSPIRATIONAL COLLECTION OF THE ADDRESSES OF HAZRAT KHALIFATUL MASIH V MAY ALLAH BE HIS HELPER By Isha'at Department Lajna Immaillah UK 2021 Qualities of a True Ahmadi Muslim An inspirational collection of the addresses of Hazrat Khalifatul Masih V (May Allah be his Helper) Isha'at Department Lajna Immaillah UK 2021 Qualities of a True Ahmadi Muslim Friday Sermons delivered by Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad, Khalifatul Masih V (May Allah be his Helper) First Published in the UK: 2021 © Islam International Publications Ltd. Published by Lajna Imaillah UK Iwan e Nusrat Jahan Unit B, Endeavour Place Coxbridge, Business Park Farnham, Surrey GU10 5EH Printed in the UK at: Raqeem Press, Farnham No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, copying or information storage and retrieval systems without permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-1-84880-765-5 Contents: 1. An Inspirational Friday Sermon Delivered by Hazrat Khalifatul Masih V (may Allah be his Helper) ………………………… 1 (on 26th October 2018, Baitul Sami’ Mosque, Houston, USA) 2. An Inspirational Friday Sermon Delivered by Hazrat Khalifatul Masih V (may Allah be his Helper) ………………………..41 (on 2nd November 2018, Baitur Rahman Mosque, Maryland, USA) An Inspirational Friday Sermon Delivered by Hazrat Khalifatul-Masih V (may Allah be his Helper) On 26th October 2018, Baitul Sami’ Mosque Houston, USA 1 After reciting the Tashahhud, Ta‘awuz, and Surah al-Fatihah, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Vaba stated: It is a great favour of God Almighty upon us that through His grace He has enabled us to accept the Promised Messiahas. -

The Tablighi Jama'at in Southeast Asia

Noor · Islam on the Move the on Islam Islam on the Move The Tablighi Jama’at in Southeast Asia Farish A. Noor amsterdam university press islam on the move Islam on the move The Tablighi Jama’at in Southeast Asia Farish A. Noor Cover illustration: Tablighis preparing for sleep at the Tablighi Jama’at Markaz in Jakarta. Illustration by Farish A. Noor, 2003 Cover design: Maedium, Utrecht Lay-out: V3-Services, Baarn isbn 978 90 8964 439 8 e-isbn 978 90 4851 682 7 (pdf) e-isbn 978 90 4851 683 4 (ePub) nur 717 © Farish A. Noor / Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2012 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (elec- tronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. For Amy Table of Contents A Note on Proper Names and the Spelling Used in This Book 11 Glossary 13 Introduction Brother Bismillah and My Introduction to the Tablighi Jama’at 17 I At Home Across the Sea The Arrival of the Tablighi Jama’at and Its Spread Across Southeast Asia 27 A network among many: Locating the Tablighi Jama’at in an overcrowded Southeast Asia 30 Landfall and homecoming: The Tablighi arrive in Southeast Asia 33 Touchdown in Jakarta: The arrival and spread of the Tablighi Jama’at across Java 35 Go east, Tablighi: The Tablighi Jama’at’s expansion to Central Java, 1957-1970s 38 Go further east, Tablighi: -

Islam and the Lahore Ahmadiyya Community

From: www.ahmadiyya.org Islam and the Lahore Ahmadiyya Community Address in Committee Room 6 of the House of Commons, London, 19th November 2014 by Dr Abdul Karim Saeed Hazrat Ameer (World-wide Head) of the Lahore Ahmadiyya Community ‘And if your Lord had pleased, all those who are in the earth would have been believers, all of them. Will you (O Prophet) then force people till they are believers?’ — The Holy Quran, 10:99 Members of the honourable Houses of Lords and Commons, and ladies and gentlemen: Firstly, I am thankful that British law and traditions have made it possible for Muslims not only to live in the UK but also practice and preach their faith, Islam, with complete freedom, freedom from discrimination and freedom from harassment. Secondly, my respectful thanks are due to all the successive Governments of this country for promoting tolerance of various religions, and to the British people for living in peace and harmony with Muslims who are settled here. My first visit to UK was about 40 years back, and it was love at first sight with UK in general and London in particular. Tower Bridge, Big Ben and the Houses of Parliament with the River Thames were a captivating sight. Not in my wildest dreams could I have imagined that one day I would be standing right inside the Houses of Parliament addressing a gathering. It was in London that I qualified as MRCP UK from the Royal College of Physicians and was later honoured by that prestigious institution which granted me its fellowship, FRCP, in recognition of my services to medical education.