Hualapai Tribe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arizona Fishing Regulations 3 Fishing License Fees Getting Started

2019 & 2020 Fishing Regulations for your boat for your boat See how much you could savegeico.com on boat | 1-800-865-4846insurance. | Local Offi ce geico.com | 1-800-865-4846 | Local Offi ce See how much you could save on boat insurance. Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states or all GEICO companies. Boat and PWC coverages are underwritten by GEICO Marine Insurance Company. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, D.C. 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. TowBoatU.S. is the preferred towing service provider for GEICO Marine Insurance. The GEICO Gecko Image © 1999-2017. © 2017 GEICO AdPages2019.indd 2 12/4/2018 1:14:48 PM AdPages2019.indd 3 12/4/2018 1:17:19 PM Table of Contents Getting Started License Information and Fees ..........................................3 Douglas A. Ducey Governor Regulation Changes ...........................................................4 ARIZONA GAME AND FISH COMMISSION How to Use This Booklet ...................................................5 JAMES S. ZIELER, CHAIR — St. Johns ERIC S. SPARKS — Tucson General Statewide Fishing Regulations KURT R. DAVIS — Phoenix LELAND S. “BILL” BRAKE — Elgin Bag and Possession Limits ................................................6 JAMES R. AMMONS — Yuma Statewide Fishing Regulations ..........................................7 ARIZONA GAME AND FISH DEPARTMENT Common Violations ...........................................................8 5000 W. Carefree Highway Live Baitfish -

Water Resources of Bill Williams River Valley Near Alamo, Arizona

Water Resources of Bill Williams River Valley Near Alamo, Arizona GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1360-D DEC 10 1956 Water Resources of Bill Williams River Valley Near Alamo, Arizona By H. N. WOLCOTT, H. E. SKIBITZKE, and L. C. HALPENNY CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1360-D An investigation of the availability of water in the area of the Artillery Mountains manganese deposits UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1956 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price 45 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Abstract....................................................................................................................................... 291 Introduction................................................................................................................................. 292 Purpose.................................................................................................................................... 292 Location................................................................................................................................... 292 Climatological data............................................................................................................... 292 History of development........................................................................................................ -

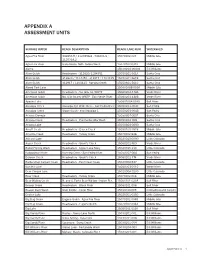

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

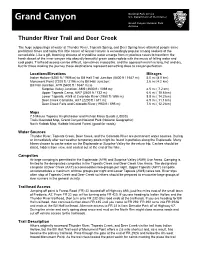

Thunder River Trail and Deer Creek

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon Grand Canyon National Park Arizona Thunder River Trail and Deer Creek The huge outpourings of water at Thunder River, Tapeats Spring, and Deer Spring have attracted people since prehistoric times and today this little corner of Grand Canyon is exceedingly popular among seekers of the remarkable. Like a gift, booming streams of crystalline water emerge from mysterious caves to transform the harsh desert of the inner canyon into absurdly beautiful green oasis replete with the music of falling water and cool pools. Trailhead access can be difficult, sometimes impossible, and the approach march is long, hot and dry, but for those making the journey these destinations represent something close to canyon perfection. Locations/Elevations Mileages Indian Hollow (6250 ft / 1906 m) to Bill Hall Trail Junction (5400 ft / 1647 m): 5.0 mi (8.0 km) Monument Point (7200 ft / 2196 m) to Bill Hall Junction: 2.6 mi (4.2 km) Bill Hall Junction, AY9 (5400 ft / 1647 m) to Surprise Valley Junction, AM9 (3600 ft / 1098 m): 4.5 mi ( 7.2 km) Upper Tapeats Camp, AW7 (2400 ft / 732 m): 6.6 mi ( 10.6 km) Lower Tapeats, AW8 at Colorado River (1950 ft / 595 m): 8.8 mi ( 14.2 km) Deer Creek Campsite, AX7 (2200 ft / 671 m): 6.9 mi ( 11.1 km) Deer Creek Falls and Colorado River (1950 ft / 595 m): 7.6 mi ( 12.2 km) Maps 7.5 Minute Tapeats Amphitheater and Fishtail Mesa Quads (USGS) Trails Illustrated Map, Grand Canyon National Park (National Geographic) North Kaibab Map, Kaibab National Forest (good for roads) Water Sources Thunder River, Tapeats Creek, Deer Creek, and the Colorado River are permanent water sources. -

The Colorado River: Lifeline Of

4 The Colorado River: lifeline of the American Southwest Clarence A. Carlson Department of Fishery and Wildlife Biology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA 80523 Robert T. Muth Larval Fish Laboratory, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA 80523 1 Carlson, C. A., and R. T. Muth. 1986. The Colorado River: lifeline of the American Southwest. Can. J. Fish. Aguat. Sci. In less than a century, the wild Colorado River has been drastically and irreversibly transformed into a tamed, man-made system of regulated segments dominated by non-native organisms. The pristine Colorado was characterized by widely fluctuating flows and physico-chemical extremes and harbored unique assemblages of indigenous flora and fauna. Closure of Hoover Dam in 1935 marked the end of the free-flowing river. The Colorado River System has since become one of the most altered and intensively controlled in the United States. Many main-stem and tributary dams, water diversions, and channelized river sections now exist in the basin. Despite having one of - the most arid drainages in the world, the present-day Colorado River supplies more water for consumptive use than any river in the United States. Physical modification of streams and introduction of non-native species have adversely impacted the Colorado's native biota. This paper treats the Colorado River holistically as an ecosystem and summarizes current knowledge on its ecology and management. "In a little over two generations, the wild Colorado has been harnessed by a series of dams strung like beads on a thread from the Gulf of California to the mountains of Wyoming. -

Analysis of Sediment Dynamics in the Bill Williams River, Arizona

Analysis of sediment dynamics in the Bill Williams River, Arizona Andrew C. Wilcox and Franklin Dekker Department of Geosciences Center for Riverine Science and Stream Renaturalization University of Montana Missoula, MT 59812-1296 Paul Gremillion (Northern Arizona University) and David Walker (University of Arizona) Collaborators: Patrick Shafroth (USGS), Cliff Riebe (University of Wyoming), Kyle House (USGS), John Stella (State University of New York) Report prepared for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, via Rocky Mountains Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (RM-CESU) February 6, 2013 DRAFT FINAL REPORT Table of Contents Executive summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 4 Catchment Erosion Rates and Sediment Mixing in a Dammed Dryland River ............................. 11 Dryland River Grain-Size Variation due to Damming, Tributary Confluences, and Valley Confinement ................................................................................................................................. 28 Analysis of Sediment Dynamics in the Bill Williams River, Arizona: Hydroacoustic Surveys and Sediment Coring ............................................................................................................................ 46 Coupled Hydrogeomorphic and Woody-Seedling Responses to Controlled Flood -

Salinity of Surface Water in the Lower Colorado River Salton Sea Area

Salinity of Surface Water in The Lower Colorado River Salton Sea Area GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 486-E Salinity of Surface Water in The Lower Colorado River- Salton Sea Area By BURDGE IRELAN WATER RESOURCES OF LOWER COLORADO RIVER SALTON SEA AREA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 486-E UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1971 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 72 610761 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Price 50 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract . _.._.-_. ._...._ ..._ _-...._ ...._. ._.._... El Ionic budget of the Colorado River from Lees Ferry to Introduction .._____. ..... .._..__-. - ._...-._..__..._ _.-_ ._... 2 Imperial Dam, 1961-65 Continued General chemical characteristics of Colorado River Tapeats Creek .._________________.____.___-._____. _ E26 water from Lees Ferry to Imperial Dam ____________ 2 Havasu Creek __._____________-...- _ __ -26 Lees Ferry .._._..__.___.______.__________ 4 Virgin River ..__ .-.._..-_ --....-. ._. 26 Grand Canyon ................._____________________..............._... 6 Unmeasured inflow between Grand Canyon and Hoover Dam ..........._._..- -_-._-._................-._._._._... 8 Hoover Dam .__-.....-_ .... .-_ . _. 26 Lake Havasu - -_......_....-..-........ .........._............._.... 11 Chemical changes in Lake Mead ............-... .-.....-..... 26 Imperial Dam .--. ........_. ...___.-_.___ _.__.__.._-_._.___ _ 12 Bill Williams River ......._.._......__.._....._ _......_._- 27 Mineral burden of the lower Colorado River, 1926-65 . -

Supplemental Materials and Information: CRB Geography

Supplemental Materials and Information: CRB Geography Study Area Detail The 283,384 km2 Upper Colorado River Basin (UCRB) drains the West Slope of the Rocky Mountains and the stratigraphically largely undeformed Colorado Plateau section of the Rocky Mountains geologic province. Colorado Plateau strata range in age from early Proterozoic (1.84 billion years ago) metamorphic crystalline basement rock, to Precambrian through early Cenozoic sedimentary strata, with late Cenozoic basalts [32], and ranging in elevation from 4352 m down to 350 m on Lake Mead Reservoir. Every natural CRB tributary we have examined thus far arises from springs, springfed wetlands, or small groundwater-fed lakes e.g., [21]. For example, UCRB mainstream flow arises from two primary sources [12,13]. The 1112 km-long Green River sources at an unnamed springfed fen 2 km southwest of Mt. Wilson in the Wind River Range in Sublette County, Wyoming, and also receives surface snowmelt water from Minor Glacier and other snowfields near Gannet Peak (4087 m). Along its course, the Green River receives flow from the Yampa and White Rivers, and delivers a long-term mean discharge at its mouth of 173 m3/sec. Similarly, the upper Colorado River similarly arises from a springfed fen at La Poudre Pass in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, and receives flow downstream from the Gunnison, Dolores, and other rivers and streams [13]. Downstream from the Green and Colorado Rivers confluence in Canyonlands National Park, Utah the mainstream is joined by the flows of: the Fremont/Muddy, San Juan, and Escalante Rivers in Lake Powell Reservoir, and the Paria River near Lees Ferry, Arizona. -

Ca-Lower-Colorado-River-Valley-Pkwy

I • I I I ) I I A REPORT TO THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES ---1 I 'I I I I THE LOWER I COLORADO I RIVER I VALLEY • PARKWAY I I D- '°'le> F; 1-e. ·• NFS- ' f\CAc:.+... \ V"C. , ~ P,of>oseol I ~~~~=-'~c f~l~~c~~w I THE LOWER COLORADO I filVERVALLEYPARKWAY I I I A proposal for a National Parkway and Scenic Recreation Road System along the Lower Colorado River Valley in 'I California, Arizona, and Nevada. I NATIONAL PARK .i DENVER SEfiViC I ·-.-:. a.t ..1flkllb""ll.--';,.i. n II"~ r.· " •· \..' ;: · I ;:~::::.;.;:;.:J I I I U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service I in cooperation with Lower Colorado River Office Bureau of Land Management • PLE~\SE RtTUR?j TO: I February 1969 I , lJnited States Department of the Interior OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY I WASHINGTON, D.C. 20240 I I Dear Mr. President: We are pleased to transmit herewith. a report on the feasibility anc;l desirability of developing a nation~l p;;i.rkwa,y and sc;enic recreation I road system within. the Lower C9l9rado River· Vaiiey in Arizona, Califo~nia, and Nevada, from the Lake Mead National Recreation I Area and Davis Dam on the north to the International Boup.d:;i.ry ~ith Mexico on the south in: the vicinity of San Luis, Arizqna arid Mexic.o.· . ·. ' .. ·.' . ·. I This :i;eport is based on ci. study 11,'lade by the Lower Col<;>rado River Office ap.d the NatiQnal :Par~ Service pf this Depa.rtmep.t with engineerin.g assistance by the Buqlau of Public Roads of the Departmep.t of . -

The Rye Creek Project: Archaeology in the Upper Tonto Basin

The Rye Creek Project: Archaeology in the Upper Tonto Basin Volume 3: Synthesis and Conclusions Mark D. Elson Douglas B. Craig Contributions by Walter H. Birkby Maria H. Czuzak William L. Deaver Alan Ferg Laura C. Fulginiti Elizabeth Miksa Henry Wallace Center for Desert Archaeology Anthropological Papers No. 11 The Rye Creek Project: Archaeology in the Upper Tonto Basin Volume 3: Synthesis and Conclusions Mark D. Elson Douglas B. Craig Contributions by Walter H. Birkby Maria H. Czuzak William L. Deaver Alan Ferg Laura C. Fulginiti Elizabeth J. Miksa Henry D. Wallace Submitted to Arizona Department of Transportation Phoenix, Arizona Contract No. 88-36 Center for Desert Archaeology Anthropological Papers No. 11 1992 ii Cover Center for Desert Archaeology 3975 North Tucson Boulevard Tucson, Arizona 85716 (602) 881-2244 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................. vii LIST OF TABLES ................................................................. ix PART 5: SYNTHESIS AND CONCLUSIONS ........................................... 1 23. WESTERN APACHE AND YAVAPAI POTTERY AND FEATURES FROM THE RYE CREEK PROJECT By Alan Ferg ................................... 3 WESTERN APACHE AND YAVAPAI HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY IN THE RYE CREEK AREA .................................................... 3 Ethnographic Information for the Area . 3 Western Apache and Yavapai Archaeological Remains .............................. 7 THE DEER CREEK SITE, AZ 0:15:52 ............................................ 8 Feature -

Roadmap for Considering Water for Arizona's Natural Areas

Roadmap for Considering Water for Arizona’s Natural Areas Kelly Mott Lacroix, Brittany Xiu, and Sharon B. Megdal December 2014 The University of Arizona Water Resources Research Center (WRRC) promotes understanding of critical state and regional water management and policy issues through research, community outreach, and public education. The Water Research and Planning Innovations for Dryland Systems (Water RAPIDS) program at the WRRC specializes in assisting Arizona communities with their water and natural resources planning needs. The goal of the Water RAPIDS program is to help communities balance securing future water supplies for residential, commercial, industrial, and agricultural demands with water needs of the natural environment. An electronic version of the Roadmap for Considering Water for Arizona’s Natural Areas and information on other Water RAPIDS programs can be found at wrrc.arizona.edu/waterrapids Acknowledgments We thank Emilie Brill Duisberg, who provided substantial editing support for this final Roadmap report. The Water RAPIDS team would also like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance on the project by former WRRC staff member Joanna Nadeau, who together with Dr. Sharon Megdal, wrote the grant proposal for this project and ushered it through its first year. The project has benefited greatly from the assistance of WRRC students Leah Edwards, Christopher Fullerton, Darin Kopp, Kathryn Bannister, and Ashley Hullinger and consultant Tahnee Roberson from Southwest Decision Resources. The WRRC is also incredibly thankful for the many hours contributed by the people concerned about water management throughout Arizona, who came to the table to discuss water for natural areas. Among these many stakeholders were our Roadmap Steering Committee: Karletta Chief, Rebecca Davidson, Chad Fretz, Leslie Meyers, Wade Noble, Joseph Sigg, Linda Stitzer, Robert Stone, Warren Tenney, Christopher Udall, Summer Waters, and David Weedman. -

Study Proposal Guidelines

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Grand Canyon National Park Research Office 1824 S. Thompson Street, Suite 200 Flagstaff, AZ 86001 928-638-7447 GUIDELINES FOR STUDY PROPOSALS Your proposal should include each of the required information items listed below, in enough detail that an educated non-specialist can understand exactly what you plan to do. If you have already prepared a relevant proposal for a funding application, work plan, formal agreement, or similar document, then your original proposal likely will satisfy NPS proposal requirements. The primary area where new information may be necessary concerns the ability of the park to assess what, if any, impacts your research may have on park resources. You should compare your original proposal to these guidelines to be certain that you have provided all the required information. If additional information is required, you can provide it to the Research Coordinator as a supplement to your proposal, as appropriate. If a required topic does not apply to your proposed study, simply list the topic and write “non-applicable.” The length of your proposal depends primarily on the complexity of the work planned. In some cases, a proposal may consist of 1-2 pages for a study expected to have no significant impact on park resources or visitor experiences. However, proposals for lengthy or complex research problems, for extensive collecting, and for work with special status species of sensitive cultural resources are typically longer, more detailed, and well-organized. Incomplete, disorganized, or illegible proposals will be returned for revision. I. INTRODUCTION A. Title B.