Roadmap for Considering Water for Arizona's Natural Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arizona Fishing Regulations 3 Fishing License Fees Getting Started

2019 & 2020 Fishing Regulations for your boat for your boat See how much you could savegeico.com on boat | 1-800-865-4846insurance. | Local Offi ce geico.com | 1-800-865-4846 | Local Offi ce See how much you could save on boat insurance. Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states or all GEICO companies. Boat and PWC coverages are underwritten by GEICO Marine Insurance Company. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, D.C. 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. TowBoatU.S. is the preferred towing service provider for GEICO Marine Insurance. The GEICO Gecko Image © 1999-2017. © 2017 GEICO AdPages2019.indd 2 12/4/2018 1:14:48 PM AdPages2019.indd 3 12/4/2018 1:17:19 PM Table of Contents Getting Started License Information and Fees ..........................................3 Douglas A. Ducey Governor Regulation Changes ...........................................................4 ARIZONA GAME AND FISH COMMISSION How to Use This Booklet ...................................................5 JAMES S. ZIELER, CHAIR — St. Johns ERIC S. SPARKS — Tucson General Statewide Fishing Regulations KURT R. DAVIS — Phoenix LELAND S. “BILL” BRAKE — Elgin Bag and Possession Limits ................................................6 JAMES R. AMMONS — Yuma Statewide Fishing Regulations ..........................................7 ARIZONA GAME AND FISH DEPARTMENT Common Violations ...........................................................8 5000 W. Carefree Highway Live Baitfish -

Water Resources of Bill Williams River Valley Near Alamo, Arizona

Water Resources of Bill Williams River Valley Near Alamo, Arizona GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1360-D DEC 10 1956 Water Resources of Bill Williams River Valley Near Alamo, Arizona By H. N. WOLCOTT, H. E. SKIBITZKE, and L. C. HALPENNY CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1360-D An investigation of the availability of water in the area of the Artillery Mountains manganese deposits UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1956 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price 45 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Abstract....................................................................................................................................... 291 Introduction................................................................................................................................. 292 Purpose.................................................................................................................................... 292 Location................................................................................................................................... 292 Climatological data............................................................................................................... 292 History of development........................................................................................................ -

Historical Geomorphology of the Verde River

Historical Geomorphology of the Verde River by Philip A. Pearthree Arizona Geological Survey Open-File Report 96-13 June, 1996 Arizona Geological Survey 416 W. Congress, Suite #100, Tucson, Arizona 85701 Research conducted in cooperation with CH2MHILL as part of the basic data collection for assessment of river navigability in Arizona at the time of Statehood (1912 J. Funding was provided by the Arizona State Land Department This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with Arizona Geological Survey standards Introduction The Verde River drainage is a major river system that heads in Big Chino Valley in north central Arizona, flows generally southeast through the rugged terrain of central Arizona, and empties into the Salt River east of the Phoenix metropolitan area. It is unusual in Arizona because much the main channel of the Verde River is perennial for much its length. Data summarized in this report were gathered to aid in the assessment of the navigability of the Verde River in February, 1912, when Arizona became a State. These investigations were conducted in cooperation with CH2MHill and were funded by the Arizona State Land Department. The purposes of this report are to (1) outline the geologic and geomorphic framework of the Verde River, (2) to describe the physical character of the channel of the Verde River, and (3) to evaluate how channel morphology and position have changed in the past century. Physiography, Geology, and General Geomorphology of the River The Verde River heads in and flows through the rugged highlands and valleys of central Arizona (Figure 1). -

June 2021 Arizona Office of Tourism Monthly State Parks Visitation Report

June 2021 Arizona Office of Tourism Monthly State Parks Visitation Report Arizona State Park Visitation June June 2021 2020 YTD State Park % Chg 2021 2020 YTD YTD % Chg Alamo Lake SP 1,237 1,924 -35.7% 48,720 46,871 3.9% Buckskin Mountain SP 11,092 9,292 19.4% 49,439 45,627 8.4% Catalina SP 6,598 2,420 172.6% 154,763 156,234 -0.9% Cattail Cove SP 10,138 14,908 -32.0% 52,221 67,256 -22.4% Colorado River SHP 167 57 193.0% 2,589 6,220 -58.4% Dead Horse Ranch SP 17,142 18,748 -8.6% 126,799 120,044 5.6% Fool Hollow Lake RA 16,380 25,104 -34.8% 55,360 63,341 -12.6% Fort Verde SHP 706 521 35.5% 4,672 2,654 76.0% Granite Mountain Hotshots MSP 1,076 1,380 -22.0% 11,778 14,874 -20.8% Homolovi SP 4,032 1,982 103.4% 22,007 11,470 91.9% Jerome SHP 4,099 1,991 105.9% 21,789 14,109 54.4% Kartchner Caverns SP 7,776 2,045 280.2% 44,020 57,663 -23.7% Lake Havasu SP 66,040 74,493 -11.3% 241,845 337,920 -28.4% Lost Dutchman SP 4,198 3,651 15.0% 122,844 132,399 -7.2% Lyman Lake SP 11,169 10,625 5.1% 30,755 38,074 -19.2% McFarland SHP 166 0 1,213 2,942 -58.8% Oracle SP 270 486 -44.4% 6,994 9,191 -23.9% Patagonia Lake SP 25,058 30,706 -18.4% 118,311 126,873 -6.7% Picacho Peak SP 1,893 1,953 -3.1% 64,084 68,800 -6.9% Red Rock SP 12,963 6,118 111.9% 56,356 33,228 69.6% Riordan Mansion SHP 777 0 2,188 2,478 -11.7% River Island SP 2,623 3,004 -12.7% 18,089 19,411 -6.8% Roper Lake SP 8,049 12,394 -35.1% 52,924 49,738 6.4% Slide Rock SP 54,922 33,491 64.0% 231,551 110,781 109.0% Tombstone Courthouse SHP 2,875 1,465 96.2% 18,261 16,394 11.4% Tonto Natural Bridge SP 8,146 7,161 13.8% 54,950 36,557 50.3% Tubac Presidio SHP 261 117 123.1% 4,240 2,923 45.1% Yuma Territorial Prison SHP 2,206 1,061 107.9% 28,672 26,505 8.2% Total All Parks 282,059 267,097 5.6% 1,647,434 1,620,577 1.7% Note: Dankworth Pond SP data is included in Roper Lake SP, Sonoita Creek SNA is included in Patagonia Lake SP and Verde River Greenway SNA is included in Dead Horse Ranch SP. -

Fossil Creek Hydrology & Travertine Geomorphology

Fossil Creek Hydrology & Travertine Geomorphology FERC Project No. 2069-003 Arizona Childs and Irving Hydropower License Prepared For: Arizona Public Service Company Phoenix, Arizona Prepared By: W.L. Bouchard & Associates, Inc. Phoenix, Arizona June 25, 1998 Fossil Creek Hydrology & Travertine Geomorphology Abstract Fossil Creek is a tributary of the Verde River in Gila and Yavapai Counties in Arizona. Stream flow is composed of a 43 cubic foot per second (cfs) base flow from Fossil Springs (a perennial source of spring flow to the creek) and runoff from precipitation which frequently occurs as destructive flash floods. These sources form 77% and 23% of the flow respectively. Fossil Springs water is supersaturated with calcium carbonate and carbon dioxide and thus tends to precipitate travertine in the upper 4 mile reach of this 14 mile stream. Travertine deposition effects stream morphology. Fossil Creek is a "flashy" stream that frequently conveys large volumes of water very quickly. Significant floods that overflow the low flow channel banks and transport significant quantities of sediment and debris Occur about every other year. These frequent flood flows tend to alter travertine deposition. Periodically, Fossil Creek is subject to very large destructive floods that significantly alter stream morphology. Arizona Public Service Company (APS) owns and operates the Childs & Irving Hydroelectric plants on Fossil Creek. The plants withdraw the 43 cfs base flow about 0.2 miles below the springs for hydropower generation. In 1992, APS proposed to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to increase minimum flow releases to 10 cfs in the Irving reach and 5 cfs in the Childs reach as part of their application for relicensing. -

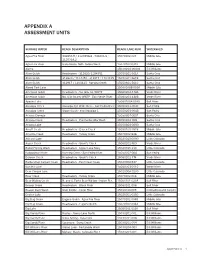

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

Synthesis of Upper Verde River Research and Monitoring 1993-2008

Chapter 8 A Preliminary View of Water Quality Conditions of the Upper Verde River Alvin L. Medina Introduction Stream water temperatures are of general interest because of interactive ef- fects among physical, biological, and chemical parameters of water chemistry (Langford 1990). Water temperature regimes dictate the types of aquatic flora and fauna present within the aquatic system, as well as influence the system’s susceptibility to parasites and disease. These regimes are commonly noted in critical habitat designations as potentially limiting to native fish populations of Southwestern streams (Federal Register 2007). Temperatures that approach the upper thermal tolerances of Southwest native fishes have been noted in Arizona streams (Deacon and Minckley 1974; USDI Geological Survey 2005). Of partic- ular interest are water temperatures for the UVR where spikedace (Meda fulgida) is imperiled. Recent fishery studies (Carveth and others 2006) suggest that na- tive fishes are sensitive to annual and large temperature fluctuations. Reduced growth rates have been reported for some species (Widmer and others 2006). The relationships between desert fishes and water temperature are unclear, especially given the assumption that they should be capable of acclimating to hot and cold temperatures common to the Southwest. State water managers rely on monitoring data to establish and validate water quality standards (Arizona Department of Environmental Quality 2002, 2007a, 2007b). Within the study area, the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (Arizona Department of Environmental Quality 2007b) listed the headwater sec- tion of the UVR between Granite Creek and Hell Canyon as sufficiently high to support all uses attaining all uses, while the section between Perkinsville to below Camp Verde was listed as “impaired” because of sediment and turbidity. -

Annual Reportarizona YEARS 40…Of Conserving Land and Water to Benefit People and Nature

2006 annual reportArizona YEARS 40…of conserving land and water to benefit people and nature In 1966 a group of conservation-minded citizens raised money to buy the Patagonia-Sonoita Creek Preserve, and The Nature Conservancy in Arizona was born. Over the years that followed, nature preserves throughout the state were purchased by or donated to the Conservancy. They had a common focus: protecting water and VISION: We will ensure freshwater sources are restoring the health of the land. secure and sustainable in order to support our growing population and the rich diversity of life This 40th annual report documents the natural evolution of an that depends on fresh water to thrive. We will work organization whose mission calls upon us to preserve the diversity with water users, providers and those who depend on growth to create the incentives and limits that of life on Earth. We have come to cherish Arizona’s rich biological will guide future growth and create well-planned heritage. We have learned about our vital connections with communities in the face of uncertainty created by neighboring states and other countries through a system of similar securing our future global climate change. habitats or ecoregions. We are beginning to understand how special places are vulnerable to changes that occur many miles away. And, we water now know that change can be friend and foe. Today we are working at an unprecedented scale, on critical issues not recognized 40 years ago, such as Upper San Pedro Partnership Verde River Greenway With the added urgency of the first recorded no- The Conservancy sponsored field trips and provided global warming and the decline in forest health. -

The Colorado River: Lifeline Of

4 The Colorado River: lifeline of the American Southwest Clarence A. Carlson Department of Fishery and Wildlife Biology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA 80523 Robert T. Muth Larval Fish Laboratory, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA 80523 1 Carlson, C. A., and R. T. Muth. 1986. The Colorado River: lifeline of the American Southwest. Can. J. Fish. Aguat. Sci. In less than a century, the wild Colorado River has been drastically and irreversibly transformed into a tamed, man-made system of regulated segments dominated by non-native organisms. The pristine Colorado was characterized by widely fluctuating flows and physico-chemical extremes and harbored unique assemblages of indigenous flora and fauna. Closure of Hoover Dam in 1935 marked the end of the free-flowing river. The Colorado River System has since become one of the most altered and intensively controlled in the United States. Many main-stem and tributary dams, water diversions, and channelized river sections now exist in the basin. Despite having one of - the most arid drainages in the world, the present-day Colorado River supplies more water for consumptive use than any river in the United States. Physical modification of streams and introduction of non-native species have adversely impacted the Colorado's native biota. This paper treats the Colorado River holistically as an ecosystem and summarizes current knowledge on its ecology and management. "In a little over two generations, the wild Colorado has been harnessed by a series of dams strung like beads on a thread from the Gulf of California to the mountains of Wyoming. -

Desert Sucker

Scientific Name Common Name Catostomus clarki desert sucker Bison code 010500 ____________________________________________________________ Official status Endemism ________________________ State AZ: threatened Colorado River Basin _______________________ Status/threats Introduced species and habitat alteration Distribution Presently occurs in the Virgin, Bill Williams, Salt, Verde, San Pedro, Blue, and Gila Rivers in Arizona. Occurs only in the Gila River headwaters in New Mexico and in the San Francisco River. Habitat Occupies low to high gradient riffles (0.5 to 2.0 % gradient) over pebble to cobble substrates containing water velocities of 0.5 to 1.5 cm sec. Preferred temperature of 17.5 C in Virgin River and calculated critical thermal maximums of 32-37 C. Life history and ecology Morphological complex in this species renders taxonomy difficult, however, probably more than one species exists across its range in Arizona and New Mexico. Two forms are apparent in the Virgin River basin, one in the Bill Williams basin and another form in the Bill Williams and Gila basins. Detailed genetic and morphological studies and frequent hybridization between the genera Pantosteus and Catostomus have resulted in Pantosteus being relegated to sub-generic status. Breeding Generally occurs in riffles, however, not specifically studied. Key Habitat Components: Low to high gradient riffles of moderate to swift velocity current, moderate depth (< 0.5 m), and over pebble to cobble-boulder substrate. Also in pools with moderate current. Breeding season Late winter (Jan-Feb) to early spring (March-April). Grazing effects The widespread, adaptable, and ubiquitous in addition to its generally low to high gradient riffle habitat of cobble to boulder substrates renders grazing of little potential impact to this species. -

Analysis of Sediment Dynamics in the Bill Williams River, Arizona

Analysis of sediment dynamics in the Bill Williams River, Arizona Andrew C. Wilcox and Franklin Dekker Department of Geosciences Center for Riverine Science and Stream Renaturalization University of Montana Missoula, MT 59812-1296 Paul Gremillion (Northern Arizona University) and David Walker (University of Arizona) Collaborators: Patrick Shafroth (USGS), Cliff Riebe (University of Wyoming), Kyle House (USGS), John Stella (State University of New York) Report prepared for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, via Rocky Mountains Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (RM-CESU) February 6, 2013 DRAFT FINAL REPORT Table of Contents Executive summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 4 Catchment Erosion Rates and Sediment Mixing in a Dammed Dryland River ............................. 11 Dryland River Grain-Size Variation due to Damming, Tributary Confluences, and Valley Confinement ................................................................................................................................. 28 Analysis of Sediment Dynamics in the Bill Williams River, Arizona: Hydroacoustic Surveys and Sediment Coring ............................................................................................................................ 46 Coupled Hydrogeomorphic and Woody-Seedling Responses to Controlled Flood -

Salinity of Surface Water in the Lower Colorado River Salton Sea Area

Salinity of Surface Water in The Lower Colorado River Salton Sea Area GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 486-E Salinity of Surface Water in The Lower Colorado River- Salton Sea Area By BURDGE IRELAN WATER RESOURCES OF LOWER COLORADO RIVER SALTON SEA AREA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 486-E UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1971 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 72 610761 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Price 50 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract . _.._.-_. ._...._ ..._ _-...._ ...._. ._.._... El Ionic budget of the Colorado River from Lees Ferry to Introduction .._____. ..... .._..__-. - ._...-._..__..._ _.-_ ._... 2 Imperial Dam, 1961-65 Continued General chemical characteristics of Colorado River Tapeats Creek .._________________.____.___-._____. _ E26 water from Lees Ferry to Imperial Dam ____________ 2 Havasu Creek __._____________-...- _ __ -26 Lees Ferry .._._..__.___.______.__________ 4 Virgin River ..__ .-.._..-_ --....-. ._. 26 Grand Canyon ................._____________________..............._... 6 Unmeasured inflow between Grand Canyon and Hoover Dam ..........._._..- -_-._-._................-._._._._... 8 Hoover Dam .__-.....-_ .... .-_ . _. 26 Lake Havasu - -_......_....-..-........ .........._............._.... 11 Chemical changes in Lake Mead ............-... .-.....-..... 26 Imperial Dam .--. ........_. ...___.-_.___ _.__.__.._-_._.___ _ 12 Bill Williams River ......._.._......__.._....._ _......_._- 27 Mineral burden of the lower Colorado River, 1926-65 .