Fossil Creek Hydrology & Travertine Geomorphology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Geomorphology of the Verde River

Historical Geomorphology of the Verde River by Philip A. Pearthree Arizona Geological Survey Open-File Report 96-13 June, 1996 Arizona Geological Survey 416 W. Congress, Suite #100, Tucson, Arizona 85701 Research conducted in cooperation with CH2MHILL as part of the basic data collection for assessment of river navigability in Arizona at the time of Statehood (1912 J. Funding was provided by the Arizona State Land Department This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with Arizona Geological Survey standards Introduction The Verde River drainage is a major river system that heads in Big Chino Valley in north central Arizona, flows generally southeast through the rugged terrain of central Arizona, and empties into the Salt River east of the Phoenix metropolitan area. It is unusual in Arizona because much the main channel of the Verde River is perennial for much its length. Data summarized in this report were gathered to aid in the assessment of the navigability of the Verde River in February, 1912, when Arizona became a State. These investigations were conducted in cooperation with CH2MHill and were funded by the Arizona State Land Department. The purposes of this report are to (1) outline the geologic and geomorphic framework of the Verde River, (2) to describe the physical character of the channel of the Verde River, and (3) to evaluate how channel morphology and position have changed in the past century. Physiography, Geology, and General Geomorphology of the River The Verde River heads in and flows through the rugged highlands and valleys of central Arizona (Figure 1). -

June 2021 Arizona Office of Tourism Monthly State Parks Visitation Report

June 2021 Arizona Office of Tourism Monthly State Parks Visitation Report Arizona State Park Visitation June June 2021 2020 YTD State Park % Chg 2021 2020 YTD YTD % Chg Alamo Lake SP 1,237 1,924 -35.7% 48,720 46,871 3.9% Buckskin Mountain SP 11,092 9,292 19.4% 49,439 45,627 8.4% Catalina SP 6,598 2,420 172.6% 154,763 156,234 -0.9% Cattail Cove SP 10,138 14,908 -32.0% 52,221 67,256 -22.4% Colorado River SHP 167 57 193.0% 2,589 6,220 -58.4% Dead Horse Ranch SP 17,142 18,748 -8.6% 126,799 120,044 5.6% Fool Hollow Lake RA 16,380 25,104 -34.8% 55,360 63,341 -12.6% Fort Verde SHP 706 521 35.5% 4,672 2,654 76.0% Granite Mountain Hotshots MSP 1,076 1,380 -22.0% 11,778 14,874 -20.8% Homolovi SP 4,032 1,982 103.4% 22,007 11,470 91.9% Jerome SHP 4,099 1,991 105.9% 21,789 14,109 54.4% Kartchner Caverns SP 7,776 2,045 280.2% 44,020 57,663 -23.7% Lake Havasu SP 66,040 74,493 -11.3% 241,845 337,920 -28.4% Lost Dutchman SP 4,198 3,651 15.0% 122,844 132,399 -7.2% Lyman Lake SP 11,169 10,625 5.1% 30,755 38,074 -19.2% McFarland SHP 166 0 1,213 2,942 -58.8% Oracle SP 270 486 -44.4% 6,994 9,191 -23.9% Patagonia Lake SP 25,058 30,706 -18.4% 118,311 126,873 -6.7% Picacho Peak SP 1,893 1,953 -3.1% 64,084 68,800 -6.9% Red Rock SP 12,963 6,118 111.9% 56,356 33,228 69.6% Riordan Mansion SHP 777 0 2,188 2,478 -11.7% River Island SP 2,623 3,004 -12.7% 18,089 19,411 -6.8% Roper Lake SP 8,049 12,394 -35.1% 52,924 49,738 6.4% Slide Rock SP 54,922 33,491 64.0% 231,551 110,781 109.0% Tombstone Courthouse SHP 2,875 1,465 96.2% 18,261 16,394 11.4% Tonto Natural Bridge SP 8,146 7,161 13.8% 54,950 36,557 50.3% Tubac Presidio SHP 261 117 123.1% 4,240 2,923 45.1% Yuma Territorial Prison SHP 2,206 1,061 107.9% 28,672 26,505 8.2% Total All Parks 282,059 267,097 5.6% 1,647,434 1,620,577 1.7% Note: Dankworth Pond SP data is included in Roper Lake SP, Sonoita Creek SNA is included in Patagonia Lake SP and Verde River Greenway SNA is included in Dead Horse Ranch SP. -

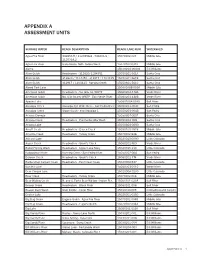

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

Synthesis of Upper Verde River Research and Monitoring 1993-2008

Chapter 8 A Preliminary View of Water Quality Conditions of the Upper Verde River Alvin L. Medina Introduction Stream water temperatures are of general interest because of interactive ef- fects among physical, biological, and chemical parameters of water chemistry (Langford 1990). Water temperature regimes dictate the types of aquatic flora and fauna present within the aquatic system, as well as influence the system’s susceptibility to parasites and disease. These regimes are commonly noted in critical habitat designations as potentially limiting to native fish populations of Southwestern streams (Federal Register 2007). Temperatures that approach the upper thermal tolerances of Southwest native fishes have been noted in Arizona streams (Deacon and Minckley 1974; USDI Geological Survey 2005). Of partic- ular interest are water temperatures for the UVR where spikedace (Meda fulgida) is imperiled. Recent fishery studies (Carveth and others 2006) suggest that na- tive fishes are sensitive to annual and large temperature fluctuations. Reduced growth rates have been reported for some species (Widmer and others 2006). The relationships between desert fishes and water temperature are unclear, especially given the assumption that they should be capable of acclimating to hot and cold temperatures common to the Southwest. State water managers rely on monitoring data to establish and validate water quality standards (Arizona Department of Environmental Quality 2002, 2007a, 2007b). Within the study area, the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (Arizona Department of Environmental Quality 2007b) listed the headwater sec- tion of the UVR between Granite Creek and Hell Canyon as sufficiently high to support all uses attaining all uses, while the section between Perkinsville to below Camp Verde was listed as “impaired” because of sediment and turbidity. -

Annual Reportarizona YEARS 40…Of Conserving Land and Water to Benefit People and Nature

2006 annual reportArizona YEARS 40…of conserving land and water to benefit people and nature In 1966 a group of conservation-minded citizens raised money to buy the Patagonia-Sonoita Creek Preserve, and The Nature Conservancy in Arizona was born. Over the years that followed, nature preserves throughout the state were purchased by or donated to the Conservancy. They had a common focus: protecting water and VISION: We will ensure freshwater sources are restoring the health of the land. secure and sustainable in order to support our growing population and the rich diversity of life This 40th annual report documents the natural evolution of an that depends on fresh water to thrive. We will work organization whose mission calls upon us to preserve the diversity with water users, providers and those who depend on growth to create the incentives and limits that of life on Earth. We have come to cherish Arizona’s rich biological will guide future growth and create well-planned heritage. We have learned about our vital connections with communities in the face of uncertainty created by neighboring states and other countries through a system of similar securing our future global climate change. habitats or ecoregions. We are beginning to understand how special places are vulnerable to changes that occur many miles away. And, we water now know that change can be friend and foe. Today we are working at an unprecedented scale, on critical issues not recognized 40 years ago, such as Upper San Pedro Partnership Verde River Greenway With the added urgency of the first recorded no- The Conservancy sponsored field trips and provided global warming and the decline in forest health. -

Desert Sucker

Scientific Name Common Name Catostomus clarki desert sucker Bison code 010500 ____________________________________________________________ Official status Endemism ________________________ State AZ: threatened Colorado River Basin _______________________ Status/threats Introduced species and habitat alteration Distribution Presently occurs in the Virgin, Bill Williams, Salt, Verde, San Pedro, Blue, and Gila Rivers in Arizona. Occurs only in the Gila River headwaters in New Mexico and in the San Francisco River. Habitat Occupies low to high gradient riffles (0.5 to 2.0 % gradient) over pebble to cobble substrates containing water velocities of 0.5 to 1.5 cm sec. Preferred temperature of 17.5 C in Virgin River and calculated critical thermal maximums of 32-37 C. Life history and ecology Morphological complex in this species renders taxonomy difficult, however, probably more than one species exists across its range in Arizona and New Mexico. Two forms are apparent in the Virgin River basin, one in the Bill Williams basin and another form in the Bill Williams and Gila basins. Detailed genetic and morphological studies and frequent hybridization between the genera Pantosteus and Catostomus have resulted in Pantosteus being relegated to sub-generic status. Breeding Generally occurs in riffles, however, not specifically studied. Key Habitat Components: Low to high gradient riffles of moderate to swift velocity current, moderate depth (< 0.5 m), and over pebble to cobble-boulder substrate. Also in pools with moderate current. Breeding season Late winter (Jan-Feb) to early spring (March-April). Grazing effects The widespread, adaptable, and ubiquitous in addition to its generally low to high gradient riffle habitat of cobble to boulder substrates renders grazing of little potential impact to this species. -

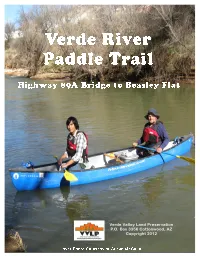

Download Paddle Map 3

Verde River Paddle Trail Highway 89A Bridge to Beasley Flat Cover Photo Courtesy of Susun McCulla Welcome to The Verde River Paddle Trail Highway 89A Bridge to Beasley Flat This paddle guide is the result of the vision and dedication of John Parsons. Many heartfelt thanks to John, his wife Susun, and his young boating partner Josh Wheeler for performing the entire field work for this guide. Special thanks to John for his decades of advocacy in support of a healthy Verde River. Photo courtesy of Gary Beverly This section of the Verde River Paddle Trail covers 31 river miles from the Highway 89A Bridgeport Bridge to Beasley Flat. The guide is composed of nine map segments, each with a corresponding descriptive narrative of GPS waypoints. A vicinity map shows how the segment maps provide coverage of each river reach, and a waypoint table provides GPS coordinates for the waypoints used in this guide. Note that much of this section of river is located on private property. Please respect the rights of these property owners during your paddle trip; it is an act of trespass to disembark and enter riverside properties. Plan your river trip accordingly and leave the river on public lands only. The Verde River is a dynamic natural resource. Water levels, channel obstructions and many other factors can change on a daily basis. River recreationists are advised to practice Safe Paddling. 1 Verde River Paddle Trail Highway 89A Bridge to Beasley Flat Safe Paddling • Never paddle alone • Inform friends and/or family of your paddling plans • Check conditions before you go • Dress appropriately for the expected weather • Wear a life jacket • Know your watercraft’s limitations • Paddle within your skill level • Avoid high, swift water • Scout any hazard about which you have doubts. -

The East Verde Is a Rapidly Degrading Stream Flowing Through a Country Of

An archeological reconnaissance of the East Verde River in central Arizona Item Type Thesis-Reproduction (electronic); text Authors Peck, Fred Rawlings,1925- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 22:17:51 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/191414 FroritespieCe The East Verde is a rapidly degradingstream flowing through a country of high relief. AN AtC HEOLOGICAL RECO ISANCE OF THE Ei$T VERDE RIVER IN CENTPLMIDNA by Fred R. Peck A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of M$TER OF ARTS in the Graduate College, University of Arizona l96 Approved: Director of T is Y Date /95 This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or repro- duction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

Celebrating Arizona's Rivers

River of the Month Series: April 2012 Celebrating Arizona’s Rivers Each month during Arizona’s centennial year, we will profile a different river in celebration of the state’s precious natural resources. From the mighty Colorado to the smallest ephemeral streams, these waterways have supported Arizona’s people and places for thousands of years. With good stewardship and thoughtful planning, they will continue to flow into Arizona’s next 100 years. April 2012: The Salt River If the Colorado River can be said to be the “lifeblood of the West,” the Salt River is the lifeblood of Phoenix and the surrounding communities. The story of the Salt is symbolic of the many faces of Arizona, from the river’s journey through a rugged and spectacular canyon wilderness to its essential role in cultivating the farms, industries, and development that gave rise to the sixth largest city in the U.S. in the unlikely landscape of the Sonoran Desert. In the late 1860s, a copper boom brought a flood of fortune seekers to Arizona, including prospector and farmer Jack Swilling. It is said that when Swilling noticed the remnants of canals constructed by the ancient Hohokam people, he realized the irrigation potential of the Salt River Valley. “Swilling’s Ditch” was completed in 1868 and was the first modern diversion of the Salt. The subsequent series of projects undertaken to ensure a water supply for the valley eventually became part of the Salt River Project (SRP). Today, SRP supplies water and power to many of the over four million people in the Phoenix region. -

The Significance of the Volcanic Rocks in the Fossil Creek Area, Arizona°

NEW MEXICO GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY O THIRTEENTH FIELD CONFERENCE 107 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE VOLCANIC ROCKS IN THE FOSSIL CREEK AREA, ARIZONA° F. R. TWENTER U. S. Geological Survey, Iowa City, Iowa The Fossil Creek area, which is that area south of Creek near Fossil Springs, the uppermost beds are at an West Clear Creek on Figure 1, is a jumble of volcanic rocks elevation of about 5,800 feet. For the most part, those — cinder cones, basaltic lavas, pyroclastics, and tuffaceous rocks that form the steep canyon walls are horizontal or sediments monopolize the landscape. This area is parti- nearly so, and are unbroken by major faults; therefore the cularly interesting, because it shows the relationship of the thickness given for the volcanic rocks probably is not ex- volcanic rocks to others in Verde Valley and in Tonto aggerated because of structure. Basin, a basin just southeast of the area shown on Figure East of Fossil Springs, flat-lying Paleozoic rocks, which 1, and because it provides a better understanding of the represent a part of the ancestral Mogollon Rim, are ex- geologic history of the Basin and Range and Colorado posed to an elevation of more than 6,000 feet. Here the Plateaus Provinces. volcanic rocks are absent, or occur only as a thin cap rock. The change from volcanic rocks west of Fossil Springs to sedimentary rocks of Paleozoic age east of the springs occurs in a lateral distance of less than 1 mile. The dis- cordant contact between the volcanic rocks and the Paleo- zoic rocks, which also is well exposed in West Clear Creek canyon, is attributable primarily to erosional and deposi- tional processes. -

Roadmap for Considering Water for Arizona's Natural Areas

Roadmap for Considering Water for Arizona’s Natural Areas Kelly Mott Lacroix, Brittany Xiu, and Sharon B. Megdal December 2014 The University of Arizona Water Resources Research Center (WRRC) promotes understanding of critical state and regional water management and policy issues through research, community outreach, and public education. The Water Research and Planning Innovations for Dryland Systems (Water RAPIDS) program at the WRRC specializes in assisting Arizona communities with their water and natural resources planning needs. The goal of the Water RAPIDS program is to help communities balance securing future water supplies for residential, commercial, industrial, and agricultural demands with water needs of the natural environment. An electronic version of the Roadmap for Considering Water for Arizona’s Natural Areas and information on other Water RAPIDS programs can be found at wrrc.arizona.edu/waterrapids Acknowledgments We thank Emilie Brill Duisberg, who provided substantial editing support for this final Roadmap report. The Water RAPIDS team would also like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance on the project by former WRRC staff member Joanna Nadeau, who together with Dr. Sharon Megdal, wrote the grant proposal for this project and ushered it through its first year. The project has benefited greatly from the assistance of WRRC students Leah Edwards, Christopher Fullerton, Darin Kopp, Kathryn Bannister, and Ashley Hullinger and consultant Tahnee Roberson from Southwest Decision Resources. The WRRC is also incredibly thankful for the many hours contributed by the people concerned about water management throughout Arizona, who came to the table to discuss water for natural areas. Among these many stakeholders were our Roadmap Steering Committee: Karletta Chief, Rebecca Davidson, Chad Fretz, Leslie Meyers, Wade Noble, Joseph Sigg, Linda Stitzer, Robert Stone, Warren Tenney, Christopher Udall, Summer Waters, and David Weedman. -

OUTSTANDING ARIZONA WATERS (Oaws) A.A.C

OUTSTANDING ARIZONA WATERS (OAWs) A.A.C. R18-11-112(G) 1. West Fork of the Little Colorado River, from its headwaters at 33°55'02"/109°33'30" to Government Springs at 33°59'33"/109°27'54" (approximately 9.1 river miles); 2. Oak Creek, from its headwaters at 35°01'30"/111°44'12" to its confluence with the Verde River at 34°40'41"/111°56'30 (approximately 50.3 river miles); 3. West Fork of Oak Creek, from its headwaters at 35°02'44"/111°54'48" to its confluence with Oak Creek at 34°59'14"/111°44'46" (approximately 15.8 river miles); 4. Peeples Canyon Creek, from its headwaters at 34°23'57"/113°19'45" to its confluence with the Santa Maria River at 34°20'36"/113°15'12" (approximately 8.1 river miles); 5. Burro Creek, from its headwaters at 34°52'46.5"/113°05'13.5" to its confluence with Boulder Creek at 34°374.5"/113°18'36" (approximately 29.5 miles); 6. Francis Creek, from its headwaters at 34°54'38"/113°20'30" to its confluence with Burro Creek at 34°44'29"/113°14'37" (approximately 22.9 river miles); 7. Bonita Creek, from its boundary of the San Carlos Indian Reservation at 33°03'08"/109°33'41" to its confluence with the Gila River at 32°53'36"/109°28'43" (approximately 14.7 river miles); 8. Cienega Creek, from its confluence with Gardner Canyon and Spring Water Canyon at 31°47'38.5"/110°35'21.5" to the USGS gaging station at 32°02'09"/110°40'34" (approximately 28.3 river miles); 9.