The Zebra-Striped Horse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Archer Files: the Complete Short Stories of Lew Archer, Private Investigator Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE ARCHER FILES: THE COMPLETE SHORT STORIES OF LEW ARCHER, PRIVATE INVESTIGATOR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ross Macdonald,Tom Nolan | 592 pages | 21 Jul 2015 | Vintage Crime/Black Lizard | 9781101910122 | English | United States The Archer Files: The Complete Short Stories of Lew Archer, Private Investigator PDF Book The final piece in this book "Winnipeg " is actually pretty god and moving and I do wonder what McDonalds might have been if he had steered away from detective fiction and swum more in the mainstream. Buy this book The Chill I'm not yet familiar with the lengthier works, but I have to think these short stories would be a great and enjoyable introduction. James M. From the Library of America. Elliott Chaze. Showing It is modelled on or a homage to Macdonald's favourite book, The Great Gatsby. The prominence of broken homes and domestic problems in his fiction has its roots in his youth. Though there's an omnipresent post-war Los Angeles backdrop, the city and the broader Southern California milieu are much less of a character than in Chandler's work. Error rating book. At the tone, l eave your name and number and I'll get back to you We are experiencing technical difficulties. The trouble is that most of them are married. Salanda, is desparately protective of his young daughter, Ella, and she is just old enough to get into all sorts of problems. Buy the Blu-Ray But I give MacDonald the edge on plotting. In fact, at the risk of being heretical, Macdonald was a much better novelist than Chandler. -

Dante's Political Life

Bibliotheca Dantesca: Journal of Dante Studies Volume 3 Article 1 2020 Dante's Political Life Guy P. Raffa University of Texas at Austin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/bibdant Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Italian Language and Literature Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Raffa, Guy P. (2020) "Dante's Political Life," Bibliotheca Dantesca: Journal of Dante Studies: Vol. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/bibdant/vol3/iss1/1 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/bibdant/vol3/iss1/1 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Raffa: Dante's Political Life Bibliotheca Dantesca, 3 (2020): 1-25 DANTE’S POLITICAL LIFE GUY P. RAFFA, The University of Texas at Austin The approach of the seven-hundredth anniversary of Dante’s death is a propi- tious time to recall the events that drove him from his native Florence and marked his life in various Italian cities before he found his final refuge in Ra- venna, where he died and was buried in 1321. Drawing on early chronicles and biographies, modern historical research and biographical criticism, and the poet’s own writings, I construct this narrative of “Dante’s Political Life” for the milestone commemoration of his death. The poet’s politically-motivated exile, this biographical essay shows, was destined to become one of the world’s most fortunate misfortunes. Keywords: Dante, Exile, Florence, Biography The proliferation of biographical and historical scholarship on Dante in recent years, after a relative paucity of such work through much of the twentieth century, prompted a welcome cluster of re- flections on this critical genre in a recent volume of Dante Studies. -

Jingles Barn 7 Hip No

Consigned by Eisaman Equine, Agent Hip No. Barn 900 Jingles 7 Gulch Thunder Gulch.................. Line of Thunder Invisible Ink ...................... Conquistador Cielo Jingles Conquistress..................... Bay Colt; Baby Elli March 4, 2008 Conquistador Cielo Marquetry ......................... Regent's Walk Countess Marq ................. (1998) Lear Fan Ah Love ............................ Colinear By INVISIBLE INK (1998). Black-type-placed winner of $465,088, 2nd Ken- tucky Derby [G1], etc. Sire of 5 crops of racing age, 90 foals, 57 starters, 33 winners of 74 races and earning $1,102,205, including champion Blessink (Clasico Dia de la Madre, etc.), and of Fearless Eagle ($274,175, Pete Axthelm S. [L] (CRC, $57,660), etc.), Twice a Princess ($141,323), Beckham Bend (to 4, 2009, $90,520), Keynes (to 4, 2009, $48,434), Out of Ink ($42,243), Disappearing Ink ($41,810), Invisible Jazz ($40,105). 1st dam Countess Marq, by Marquetry. 3 wins at 3 and 4, $102,735, 2nd Autumn Leaves H. [L] (MNR, $15,460). Dam of 4 other registered foals, 3 of rac- ing age, 3 to race, 2 winners-- Masala (c. by Lion Heart). Winner at 2 and 3, 2009, $110,388. Paniolo (c. by Invisible Ink). Winner at 2, 2009, $19,205. 2nd dam AH LOVE, by Lear Fan. Unraced. Dam of 5 winners, including-- DIAMONDS AND LEGS (f. by Quiet American). 3 wins at 2 and 3, $91,101, Laura Gal S. (LRL, $25,680), etc. Dam of 3 foals, 2 winners-- WILD GAMS (f. by Forest Wildcat). 9 wins, 2 to 5, $1,168,171, in N.A./U.S., Thoroughbred Club of America S. -

EDITED PEDIGREE for TRANSACT (IRE)

EDITED PEDIGREE for TRANSACT (IRE) Selkirk (USA) Sharpen Up Sire: (Chesnut 1988) Annie Edge TRANS ISLAND (GB) (Bay 1995) Khubza (GB) Green Desert (USA) TRANSACT (IRE) (Bay 1990) Breadcrumb (Chesnut gelding 2005) Kris Sharpen Up Dam: (Chesnut 1976) Doubly Sure KHRISMA (GB) (Chesnut 1989) Sancta So Blessed (Brown 1979) Soft Angels 3Sx3D Sharpen Up, 4Sx4D Atan, 4Sx4D Rocchetta, 4Dx3D Soft Angels, 5Sx3D So Blessed, 5Sx5D Native Dancer, 5Sx5D Mixed Marriage, 5Sx5D Rockefella, 5Sx5D Chambiges, 5Dx4D Crepello, 5Dx4D Sweet Angel TRANSACT (IRE), won 1 race over hurdles (16f.) at 6 years and £2,315 and placed twice and won 2 races over fences (16f.) at 6 and 7 years, 2012 and £5,458 and placed 5 times. 1st Dam KHRISMA (GB), won 2 races at 3 years and £6,755 and placed 4 times; dam of 2 winners: TRANSACT (IRE), see above. TAXIARHIS (IRE) (2004 c. by Desert Sun (GB)), won 2 races in Greece at 5 years and £13,846 and placed 10 times. 2nd Dam SANCTA, won 3 races at 3 years and placed 3 times, from only 8 starts; dam of 8 winners: Wolsey (USA) (c. by Our Native (USA)), won 5 races at 2 and 3 years and £68,202, placed second in Bay Meadows Derby, Bay Meadows, Gr.3. Carmelite House (USA) (c. by Diesis), won 3 races, placed, placed fourth in Prix Eugene Adam, Saint-Cloud, Gr.2; sire. SAINT KEYNE (GB), won 2 races at 3 and 4 years and placed 5 times; also won 2 races over hurdles at 5 years and placed once. -

Headline News

HEADLINE THREE CHIMNEYS NEWS The Idea is Excellence. For information about TDN, 7 Wins in 7 Days for SMARTY JONES call 732-747-8060. Click for chart & replay of his latest winner www.thoroughbreddailynews.com WEDNESDAY, MAY 20, 2009 TDN Feature Presentation BROAD BRUSH EUTHANIZED Leading sire Broad Brush (Ack Ack--Hay Patcher, by GROUP 1 IRISH 2000 GUINEAS Hoist the Flag), pensioned since 2004, was euthanized May 15 at Gainesway Farm in Lexington, Ken- tucky, where he had stood his entire career. He was 26. Racing in the LANE’S END CONGRATULATES GUS SCHICKEDANZ, colors of breeder Robert ONE OF NORTH AMERICA’S LEADING BREEDERS Meyerhoff, the Maryland- FOR THE PAST 10 YEARS, ON HIS INDUCTION bred won seven of 14 INTO THE CANADIAN HALL OF FAME. starts at three in 1986, including the GI Wood GROUND IS RIGHT FOR RAYENI Memorial S., GI Meadow- Trainer John Oxx was yesterday contemplating the lands Cup and GIII Jim prospect of an English-Irish 2000 Guineas double as Beam S., as well as a ground conditions remained heavy at The Curragh memorable renewal of ahead of the challenge of Rayeni the GII Pennsylvania (Ire) (Indian Ridge {Ire}) in Satur- Derby. He also ran third day=s contest. Unbeaten in two in both the GI Kentucky starts, a six-furlong maiden at Derby and GI Preakness Naas and the G3 Killavullan S. at S. Sent to California at Broad Brush (1983-2009) Leopardstown on rain-softened the beginning of his four- Horsephotos ground in October, His Highness year-old campaign, the the Aga Khan=s homebred is one bay outbattled Ferdinand to capture the GI Santa Anita of few leading contenders who H. -

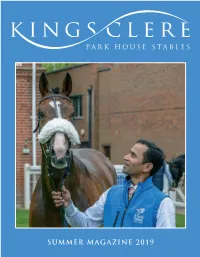

SUMMER MAGAZINE 2019 INTRODUCTION P ARK HOUSE STABLES Orse Racing Has Always Been Unpredictable and in Many Ways That Is Part of Its Attraction

P ARK HOUSE STABLES SUMMER MAGAZINE 2019 INTRODUCTION P ARK HOUSE STABLES orse racing has always been unpredictable and in many ways that is part of its attraction. It can provide fantastic high H points but then have the opposite effect on one’s emotions a moment later. Saturday 13 July was one of those days. Having enjoyed the thrill of watching Pivoine win one of the season’s most important handicaps, closely followed by Beat The Bank battling back to win a second Summer Mile, the ecstasy of victory was replaced in a split second by a feeling of total horror with Beat The Bank suffering what could immediately be seen to be an awful injury. Whilst winning races is important to everyone at Kingsclere, the vast majority of people who work in racing do it because they love horses and there is nothing more cruel in this sport than losing a horse, whether it be on the gallops or on the racecourse. Beat The Above: Ernie (Meg Armes) is judged Best Puppy at the Kingsclere Dog Show Bank was a wonderful racehorse and a great character and will be remembered with huge affection by everyone at Park House. Front cover: BEAT THE BANK with Sandeep after nishing second at Royal Ascot Whilst losing equine friends is never easy it is not as difficult as Back cover: LE DON DE VIE streaks clear on Derby Day at saying goodbye to two wonderful friends in Lynne Burns and Dr Epsom Elizabeth Harris. Lynne was a long time member of the Kingsclere Racing Club and her genial personality and sense of fun endeared CONTENTS her to everyone lucky enough to meet her. -

King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Stakes (Sponsored by QIPCO)

King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Stakes (Sponsored by QIPCO) Ascot Racecourse Background Information for the 65th Running Saturday, July 25, 2015 Winners of the Investec Derby going on to the King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Stakes (Sponsored by QIPCO) Unbeaten Golden Horn, whose victories this year include the Investec Derby and the Coral-Eclipse, will try to become the 14th Derby winner to go on to success in Ascot’s midsummer highlight, the Group One King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Stakes (Sponsored by QIPCO), in the same year and the first since Galileo in 2001. Britain's premier all-aged 12-furlong contest, worth a boosted £1.215 million this year, takes place at 3.50pm on Saturday, July 25. Golden Horn extended his perfect record to five races on July 4 in the 10-furlong Group One Coral- Eclipse at Sandown Park, beating older opponents for the first time in great style. The three-year-old Cape Cross colt, owned by breeder Anthony Oppenheimer and trained by John Gosden in Newmarket, captured Britain's premier Classic, the Investec Derby, over 12 furlongs at Epsom Downs impressively on June 6 after being supplemented following a runaway Betfred Dante Stakes success at York in May. If successful at Ascot on July 25, Golden Horn would also become the fourth horse capture the Derby, Eclipse and King George in the same year. ËËË Three horses have completed the Derby/Eclipse/King George treble in the same year - Nashwan (1989), Mill Reef (1971) and Tulyar (1952). ËËË The 2001 King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Stakes saw Galileo become the first Derby winner at Epsom Downs to win the Ascot contest since Lammtarra in 1995. -

Fnr Au ®Lh Jjraaqinu Oiqriatmaa

- ... fnr au ®lh JJraaqinuOiqriatmaa - FROM MR. and MRS. GORDON VOORHIS VOORHIS FARM MR. and MRS. FREDHERRICK Red Hook, New York & The APPLEVALEMORGANS BROADWALL GOLDEN LASS 08910 BROADWALL GOLDEN GIRL 08911 We ride our Morgans for pleasure and enjoy them. We at Broadwall Farm wish all our Morgan friends a very Merry Christmas and a very prosp erous Morgan New Year . Colts and filly youngsters for sale - also a few brood mares. A FAMOUS VERMONTER ... NOW A NEW YORKER TUTOR 10198 LIVER CHESTNUTSTALLION, FLAXEN MANE AND TAIL - WEIGHT 1150 Foaled May 2, 1949 - Height 14.3112hands Sire: Mentor 8627 - Dam: Kona 5586 Fee - $100.00 Privilege of return service within 5 months. Mares for breeding must be accompanied by veterinarian 's Health Certificate - Stable facilities for mares . CENTAUR FARMS SCHOHARIE NEW YORK SALES, TRAINING, BOARDING - PHONE AX 5-8101 or AX 5-7470 HARRY and VIRGINIA KINTZ, owners VISITORS ALWAYS WELCOME SPECIAL FEATURES The Christmas Baby . .. .. .. 9 New York State Morgan Show .................. ........................... 11 The Versatile Morgan .. .. .. .. .. .... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 13 Pennsylvania National Horse Show .. .... .. .. .. .. .... ... .. .. .. .. .. .. ..... 15 Big Bend Farms Young Stock Sale ....... .............. ....................... .. 17 Phoenix Short Course Readied .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .. 19 Th• Morgan Horse In The West ..... • ................................ ........ 21 New Books . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 31 Morgans On Parade -

Owners Thru Nov 11

Horsemen Standings Report Nov 11,2020 12:04 PM Meadowlands Harness From 09/05/2020 To 11/11/2020 Page 1 of 9 Acct# Account Name Starts Wins Places Shows Earnings 52658 Pollack Racing LLC or Jeffrey W Cullipher 96 14 9 17 $151,785.00 46673 Howard Slotoroff 26 5 5 0 $34,417.75 50922 Crawford Farms Racing 18 5 2 2 $55,240.00 52838 Thomas J Maloney 8 4 1 0 $26,475.00 45767 Joseph Martinelli, Sr. 9 4 0 1 $128,491.45 46156 Robert J Devine 8 4 0 1 $20,445.00 52289 Jenny A Bier or Joann Dombeck or Midsize Construction Inc 5 4 0 0 $41,750.00 44581 Rick D Phillips or Mark A Harder 10 3 2 1 $32,460.50 40526 Purple Haze Stables LLC 11 3 1 1 $33,600.00 39960 Shirley Levin 8 3 1 0 $29,810.00 51967 Ronald A Perone or Thomas J Maloney or Donald Kayser 12 3 0 2 $19,170.00 53069 Burke Racing Stable or Lawrence Karr or J& T Silva- Purnel& Libby or Weaver Bruscemi83 0 1 $18,190.00 46435 Boss Racing Usa 14 3 0 1 $15,900.00 53938 Noel M Daley or L A Express Stable LLC or Caviart Farms 3 3 0 0 $137,361.50 51620 Burke Racing Stable or Silva Purnel & Libby or P Collura & Weaver Bruscemi3 3 0 0 $116,923.75 53933 Pinske Stables or David K Hoese or Lawrence M Means 3 3 0 0 $91,739.25 48675 Lindy Farms Of Connecticut LLC 5 3 0 0 $26,010.31 53756 SRF Stable or Holly Lane Stud East LTD 4 3 0 0 $25,500.00 53195 Enzed Racing Stable Inc or Jerry Kovach 7 3 0 0 $22,230.00 53549 Curtin ANZ Stables 31 2 5 6 $34,317.50 10340 Royal Wire Products Inc 9 2 4 1 $65,629.63 46659 Share A Horse Inc 11 2 3 1 $24,130.00 52666 Terrence Smith 8 2 3 0 $14,000.00 51383 William Mann 15 -

Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy – Inferno

DIVINE COMEDY -INFERNO DANTE ALIGHIERI HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW ENGLISH TRANSLATION AND NOTES PAUL GUSTAVE DORE´ ILLUSTRATIONS JOSEF NYGRIN PDF PREPARATION AND TYPESETTING ENGLISH TRANSLATION AND NOTES Henry Wadsworth Longfellow ILLUSTRATIONS Paul Gustave Dor´e Released under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial Licence. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ You are free: to share – to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work; to remix – to make derivative works. Under the following conditions: attribution – you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work); noncommercial – you may not use this work for commercial purposes. Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. English translation and notes by H. W. Longfellow obtained from http://dante.ilt.columbia.edu/new/comedy/. Scans of illustrations by P. G. Dor´e obtained from http://www.danshort.com/dc/, scanned by Dan Short, used with permission. MIKTEXLATEX typesetting by Josef Nygrin, in Jan & Feb 2008. http://www.paskvil.com/ Some rights reserved c 2008 Josef Nygrin Contents Canto 1 1 Canto 2 9 Canto 3 16 Canto 4 23 Canto 5 30 Canto 6 38 Canto 7 44 Canto 8 51 Canto 9 58 Canto 10 65 Canto 11 71 Canto 12 77 Canto 13 85 Canto 14 93 Canto 15 99 Canto 16 104 Canto 17 110 Canto 18 116 Canto 19 124 Canto 20 131 Canto 21 136 Canto 22 143 Canto 23 150 Canto 24 158 Canto 25 164 Canto 26 171 Canto 27 177 Canto 28 183 Canto 29 192 Canto 30 200 Canto 31 207 Canto 32 215 Canto 33 222 Canto 34 231 Dante Alighieri 239 Henry Wadsworth Longfellow 245 Paul Gustave Dor´e 251 Some rights reserved c 2008 Josef Nygrin http://www.paskvil.com/ Inferno Figure 1: Midway upon the journey of our life I found myself within a forest dark.. -

The Ross Macdonald Collection 1St Edition Ebook

THE ROSS MACDONALD COLLECTION 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ross MacDonald | 9781598535525 | | | | | The Ross Macdonald Collection 1st edition PDF Book United Kingdom. Download Hi Res. First edition of Macdonald's "powerful" novel, the 13th in his award-winning Lew Archer series, signed on the title page by Macdonald. Follow us. Edited with an Afterword by Ralph B. Published by Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group A very nice copy indeed. Macdonald, Ross. Read it Forward Read it first. Trouble Follows Me. Add to basket. Essential We use cookies to provide our services , for example, to keep track of items stored in your shopping basket, prevent fraudulent activity, improve the security of our services, keep track of your specific preferences e. All My Best, Collin. Home Contact us Help Free delivery worldwide. Performance and Analytics. Cover by Hooks. With 8 pp. Very Rare if such were possible, in dustwrapper. Published by Bantam Books. Harry Potter. New York, New York: Delacorte Press, A just about fine copy in red and white patterned paper covered boards, black titles to the spine in a bright, fresh neatly price-clipped pictorial dustwrapper with some light use and and an old tape mend to one closed tear on the back panel on the verso. The Long Fall. Category: Crime Mysteries. Adapted into film as 'Harper' with Paul Newman. Product Details. Elizabeth George. Collin, June About this Item: Orlando, Florida, U. First Edition of the highly-regarded seventh Lew Archer mystery by Ross Macdonald, considered by critics as one of the 'holy trinity of American crime writers' with Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. -

Matthew J. Bruccoli Research Materials on Kenneth Millar MS.L.003

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft196n98kn No online items Guide to the Matthew J. Bruccoli Research Materials on Kenneth Millar MS.L.003 Processed by Special Collections and Archives staff, 2014; inventory added by Zoe MacLeod, 2020. Special Collections and Archives, University of California, Irvine Libraries (cc) 2020 The UCI Libraries P.O. Box 19557 University of California, Irvine Irvine 92623-9557 [email protected] URL: http://special.lib.uci.edu Guide to the Matthew J. Bruccoli MS.L.003 1 Research Materials on Kenneth Millar MS.L.003 Contributing Institution: Special Collections and Archives, University of California, Irvine Libraries Title: Matthew J. Bruccoli research materials on Kenneth Millar Creator: Bruccoli, Matthew J. (Matthew Joseph) Identifier/Call Number: MS.L.003 Physical Description: 5.6 Linear Feet(14 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1940-1980 Abstract: This collection contains research materials and notes for two books on Kenneth Millar by Matthew J. Bruccoli, Ross Macdonald/Kenneth Millar, A Descriptive Bibliography (1983), and Ross Macdonald (1984). It also includes Millar's manuscripts for several books and correspondence between Bruccoli and Millar. Language of Material: English . Access Collection is unprocessed. Please contact Special Collections and Archives regarding availability of materials for research use. Publication Rights Property rights reside with the University of California. Copyrights are retained by the creators of the records and their heirs. For permission to reproduce or to publish, please contact the Head of Special Collections and Archives. Preferred Citation Matthew J. Bruccoli research materials on Kenneth Millar. MS-L003. Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California.