Shroud Spectrum International No. 41 Part 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Progress of Research on the Shroud of Turin

Why we Can See the Image by Robert A. Rucker August 17, 2019 www.shroudresearch.net © 2019 Robert A. Rucker 1 Mysteries of the Shroud • Image – Why can we see the image? – How was the image formed? • Date – What is the date of the Shroud? – What about the C14 dating? • Blood – How did it get onto the Shroud? – Why is it still reddish? 2 www.shroudresearch.net • On the RESEARCH page: • Paper 5: “Information Content on the Shroud of Turin” • Paper 6: “Role of Radiation in Image Formation on the Shroud of Turin” • Paper 22: “Image Formation on the Shroud of Turin” 3 Components of Reality • Mass • Space • Time • Energy • Information – We live in the information age. 4 CAD/CAM • CAD = computer aided design • CAM = computer aided machining • 3 requirements for CAD/CAM – equipment / mechanism – energy – information 5 CAD/CAM • What information? • The information that defines the design. 6 Computer Aided Design • The design is information 7 Computer Aided Machining • Mechanism + energy + information 8 Examples of Information 1. She saw a black cat. 2. Hes wsa a calbk tac. 3. Bcs ask l ahate awc. 4. bc saSk la h.ate awc 5. ░░ ░░░░ ░░ ░░░░░ ░░░ 6. There is information in the location of the dots / pixels 9 Every image is due to Information • Newspaper • Magazine • Photograph • TV • Computer Monitor • Image on the Shroud of Turin 10 To Form Any Image • Three Requirements – Mechanism – Energy – Information • What information? – That which defines the image 11 Image on a Photograph The information that defines her appearance is encoded into the location of the pixels that form the image. -

THE SHROUD of TURIN Its Implications for Faith and Theology

I4o THEOLOGICAL TRENDS THE SHROUD OF TURIN Its implications for faith and theology ACK IN I967, a notable Anglican exegete, C; F. D. Moule, registered a B complaint about some of his contemporaries: 'I have met otherwise intelligent men who ask, apparently in all seriousness, whether there may not be truth in what I would call patently ridiculous legends about.., an early portrait of Jesus or the shroud in which he is supposed to have been buried'. 1 Through the 195os into the 196os many roman Catholics, if they had come across it, would have agreed with Moule's verdict. That work of fourteen volumes on theology and church history, which Karl Rahner and other German scholars prepared, Lexikon fiir Theologie un d Kirehe (i957-68), simply ignored the shroud of Turin, except for a brief reference in an article on Ulysse Chevalier (1841-1923). Among his other achievements, the latter had gathered 'weighty arguments' to disprove the authenticity of the shroud. Like his english jesuit contemporary, Herbert Thurston, Chevalier maintained that it was a fourteenth-century forgery. The classic Protestant theological dictionary, Die Religion in Gesehichte und Gegenwart, however, took a different view. The sixth volume of the revised, third edition, which appeared in 1962 , included an article on the shroud by H.-M. Decker-Hauff. ~ The author summarized some of the major reasons in favour of its authenticity. In its material and pattern, the shroud matches products from the Middle East in the first century of the christian era. In the mid-fourteenth century the prevailing conventions of church art would not have allowed a forger or anyone else to portray Jesus in the full nakedness that we see on the shroud. -

Forensic Aspects and Blood Chemistry of the Turin Shroud Man

Scientific Research and Essays Vol. 7(29), pp. 2513-2525, 30 July, 2012 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/SRE DOI: 10.5897/SRE12.385 ISSN 1992 - 2248 ©2012 Academic Journals Review Forensic aspects and blood chemistry of the Turin Shroud Man Niels Svensson* and Thibault Heimburger 1Kalvemosevej 4, 4930 Maribo, Denmark. 215 rue des Ursulines, 93200 Saint-Denis, France. Accepted 12 July, 2012 On the Turin Shroud (TS) is depicted a faint double image of a naked man who has suffered a violent death. The image seems to be that of a real human body. Additionally, red stains of different size, form and density are spread all over the body image and in a few instances outside the body. Forensic examination by help of different analyzing tools reveals these stains as human blood. The distribution and flow of the blood, the position of the body are compatible with the fact that the Turin Shroud Man (TSM) has been crucified. This paper analyses the already known essential forensic findings supplied by new findings and experiments by the authors. Compared to the rather minute gospel description of the Passion of the Christ, then, from a forensic point of view, no findings speak against the hypothesis that the TS once has enveloped the body of the historical Jesus. Key words: Blood chemistry, crucifixion, forensic studies, Turin Shroud. INTRODUCTION The interest of the forensic examiners for the Turin Edwards et al.,1986; Zugibe, 2005). The TSM imprint is Shroud Man (TSM) image began with Paul Vignon and made of two different kinds of features: Yves Delage at the very beginning of the 20th century, after the remarkable discovery of the “negative” charac- i) The image itself, which has most of the properties of a teristics of the Turin Shroud (TS) image allowed by the negative “photography” and, as such, is best seen on the first photography of the TS by Secondo Pia in 1898. -

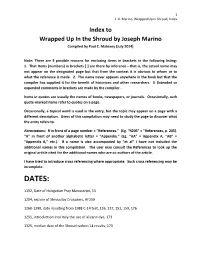

Index to Wrapped up in the Shroud by Joseph Marino Compiled by Paul C

1 J. G. Marino, Wrapped Up in Shroud, Index Index to Wrapped Up In the Shroud by Joseph Marino Compiled by Paul C. Maloney (July 2014) Note: There are 3 possible reasons for enclosing items in brackets in the following listing: 1. That Items (numbers) in brackets [ ] are there by inference—that is, the actual name may not appear on the designated page but that from the context it is obvious to whom or to what the reference is made. 2. The name never appears anywhere in the book but that the compiler has supplied it for the benefit of historians and other researchers. 3. Extended or expanded comments in brackets are made by the compiler. Items in quotes are usually the names of books, newspapers, or journals. Occasionally, such quote-marked items refer to quotes on a page. Occasionally, a topical word is used in the entry, but the topic may appear on a page with a different description. Users of this compilation may need to study the page to discover what the entry refers to. Abreviations: R in front of a page number = “References.” (Eg. “R205” = “References, p. 205). “A” in front of another alphabetic letter = “Appendix.” (Eg. “AA” = Appendix A, “AB” = “Appendix B,” etc.). If a name is also accompanied by “et al” I have not included the additional names in this compilation. The user may consult the References to look up the original article cited for the additional names who are co-authors of the article. I have tried to introduce cross referencing where appropriate. Such cross referencing may be incomplete. -

Das Turiner Grabtuch - Echtheitsdiskussion Und

Das Turiner Grabtuch - Echtheitsdiskussion und Forschungsergebnisse im historischen Überblick Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des Magistergrades an der Geisteswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Salzburg eingereicht von Arabella Martínez Miranda Salzburg, im Dezember 2000 Das Turiner Grabtuch - Echtheitsdiskussion und Forschungsergebnisse im historischen Überblick 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 VORWORT ................................................................................................................................................... 3 2 EINLEITUNG ............................................................................................................................................... 4 3 ZUM EINSTIEG: WAS IST DAS TURINER GRABTUCH - EINE BESCHREIBUNG ...................... 6 3.1 BRANDSCHÄDEN, WASSERFLECKEN, AUFGESETZTE FLICKEN, FALTEN ................................................... 7 3.2 BILD- UND BLUTSPUREN ........................................................................................................................ 10 4 DAS TURINER GRABTUCH IM BLICKPUNKT WISSENSCHAFTLICHER ANALYSEN........... 12 4.1 1898 - DIE FOTOGRAFIE ALS BEGINN DER MODERNEN WISSENSCHAFTLICHEN ERFORSCHUNG.............. 12 4.2 DAS URTEIL EINES (KATHOLISCHEN) HISTORIKERS - ULYSSE CHEVALIER ............................................ 15 4.2.1 Exkurs - die erste historisch verbürgte Ausstellung des TG .......................................................... 15 4.3 DAS GRABTUCH IM BLICKPUNKT VON BIOLOGEN UND ÄRZTEN ........................................................... -

A Critical Summary of Observations, Data and Hypotheses

TThhee SShhrroouudd ooff TTuurriinn A Critical Summary of Observations, Data and Hypotheses If the truth were a mere mathematical formula, in some sense it would impose itself by its own power. But if Truth is Love, it calls for faith, for the ‘yes’ of our hearts. Pope Benedict XVI Version 4.0 Copyright 2017, Turin Shroud Center of Colorado Preface The purpose of the Critical Summary is to provide a synthesis of the Turin Shroud Center of Colorado (TSC) thinking about the Shroud of Turin and to make that synthesis available to the serious inquirer. Our evaluation of scientific, medical forensic and historical hypotheses presented here is based on TSC’s tens of thousands of hours of internal research, the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP) data, and other published research. The Critical Summary synthesis is not itself intended to present new research findings. With the exception of our comments all information presented has been published elsewhere, and we have endeavored to provide references for all included data. We wish to gratefully acknowledge the contributions of several persons and organizations. First, we would like to acknowledge Dan Spicer, PhD in Physics, and Dave Fornof for their contributions in the construction of Version 1.0 of the Critical Summary. We are grateful to Mary Ann Siefker and Mary Snapp for proofreading efforts. The efforts of Shroud historian Jack Markwardt in reviewing and providing valuable comments for the Version 4.0 History Section are deeply appreciated. We also are very grateful to Barrie Schwortz (Shroud.com) and the STERA organization for their permission to include photographs from their database of STURP photographs. -

Is the Shroud of Turin Genuine?

Is the Shroud of Turin Genuine? William David Cline トリノの聖骸布は本物か? クライン ウィリアム デェービド Abstract The Shroud of Turin is a long cloth kept in the Cathedral of Turin, Italy. On the cloth is a faint image of a man with the marks of crucifixion. There are also bloodstains which match. When it was first photographed in 1898, worldwide interest in the Shroud arose because rather than another faint image as was expected, the photographic negative showed a positive photograph-like image of a man. This image showed considerable detail that had previously been unknown. Much controversy surrounds the Shroud because it is either related directly to Jesus Christ or it is an incredibly skillful forgery. Scientific study has also been controversial with some conclusions that contradict others. However, a review of the history and research on the Shroud reveals reasonable evidence for its authenticity. Key words : Shroud of Turin, science and religion, historical evidence of Jesus Christ (Received September 28, 2007) 抄 録 トリノの聖骸布はトリノの大聖堂に保存されている長い布です。その布には、磔にされ た人のぼんやりしたイメージが残されています。また、磔に一致する血痕も付いています。 1898年に初めて写真撮影された時、写真のネガが、ぼんやりしたイメージでなくはっきり とした人間のイメージを示したので世界中で聖骸布に対する関心が起きた。このイメージ はこれまで知られていない細部を相当に示していた。布がイエス・キリストに直接関係す るかそれとも巧妙に作られた偽物なので聖骸布に関して多くの議論が起きた。科学的研究 もある結論が他の結論を否定したりして論争の余地を残している。しかしながら、聖骸布 に関する歴史と調査研究の概観してみると聖骸布が本物であることを示す合理的な証拠が あることを示している。 キーワード:トリノの聖骸布、科学と宗教、イエス・キリストの歴史的証拠 (2007 年 9 月 28 日受理) - 79 - 大阪女学院短期大学紀要37号(2007) Introduction There are reasons for believing that the Shroud of Turin is the cloth which covered the body of Jesus Christ after his burial. On the other hand, for many people, the results of the Carbon 14 tests done on the Shroud in 1988 have settled the issue once and for all. Without further investigation, those test results have led many people to dismiss the Shroud of Turin as nothing other than a medieval forgery and fake. -

Resolución De Objeciones

RESOLUCIÓN DE OBJECIONES Andrés Brito Licenciado en CC. Eclesiásticas. Doctor en CC. de la Información. Delegado del CES en Canarias 1. Aclaración sobre el término “escéptico” Es posible hallar, sobre todo en Internet, colectivos de escépticos que plantean objeciones sobre la Sábana Santa. Acaso la más activa en España sea la Sociedad para el Avance del Pensamiento Crítico (ARP)1, editora de “El Escéptico Digital”. La idea general viene a ser la siguiente: si esta es la mortaja de un crucificado tendría que tener ciertas características que son lógicas a priori, pero como algunas no encajan en ese “a priori”, la reliquia es falsa. Sin embargo, quizá una postura más científica sería: la reliquia es un documento que hay que leer, y si eso no coincide con el prejuicio con el que nos acercamos a ella, tendremos que superar tal prejuicio para comprender lo que estamos estudiando. En el fondo, parece subsistir el convencimiento de que aceptar las conclusiones que se han expuesto sobre la Síndone supone abandonar toda esperanza de comprender los hechos científicos que se esconden tras los sucesos, de confiar en un Universo ordenado. Hemos querido compendiar los principales reparos en este apartado porque, como afirma Manuel Ordeig: “Un investigador no es escéptico, ni deja de serlo. Simplemente, investiga; muchas veces sin saber a dónde va a conducirle su estudio; al final, deduce consecuencias de los datos obtenidos. Los ‘escépticos declarados’ son en el fondo tan dogmáticos como los fideistas: la diferencia es solamente que su dogmatismo es de sentido contrario”2. Con la palabra “escéptico”, si profundizamos en el planteamiento de Ordeig, hay un problema que debería depurarse antes de seguir, y es que “escéptico” no quiere decir “objetivo”. -

History of the Mount St. Alphonsus Retreat Center

History of the Mount St. Alphonsus Retreat Center 1001 Broadway (Route 9W) PO Box 219 Esopus, NY 12429-0219 Before the Redemptorists built Mount St. Alphonsus in 1904, the land was owned by Robert Livingston Pell. Said to be the greatest fruit farm in the country, it was known for its apples and grapes, which were shipped to European markets. Pell developed a species of apples, the Newton Pippin, grown in an orchard of more than 25,000 trees. The Pell Coat of Arms included a pelican piercing its own breast to feed its young, an ancient symbol of the Eucharist. The Redemptorist community, still growing at the turn of the century, looked at property in New York, Connecticut and Pennsylvania before settling here. In 1903, they paid $57,000 for the property. The Redemptorist order bought a quarrying operation in Port Deposit, MD, to produce the granite, used in this building. Construction of the original building began in 1904 and was finished in 1907. The wing on the south end was added in later years. The property has expanded to the present 412 acres on the Hudson River. Redemptorists used the building as a seminary for the training of priests. After initial formation at St. Mary's in Northeast, PA, for six years, students made a year-long long Novitiate in Ilchester, MD, and then spent six years here at Mount St. Alphonsus. The property contained many buildings in earlier times when cattle, horses, pigs, chickens and crops that included corn, potatoes, apples and grapes were raised. The wine used for Mass was made on the property. -

Shroud of Turin

The Methods and Techniques Employed in the Manufacture of the Shroud of Turin by Nicholas Peter Legh Allen DFA, MFA, Laur Tech FA. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor.Philosophiae f:) ~tl> ~ () I- I ~ e.. AY-I-s University of Durban-Westville . Supervisor: Prof JF Butler-Adam Co-supervisor: Dr EA Mare Co-supervisor: Fr LB Renetti December 1993 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the loving memory of Prof Thomas Herbert Matthews BFA, MFA, D Litt et Phil. 1936-1993 Adversus solem ne loquitor 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This inquiry would not have been possible without the selfless contributions effected by innumerable people who have each in their particular way facilitated my attempt to resolve the curious riddle of the Shroud oJ Turin's manufacture. Indeed, most persons involved had no knowledge of the precise nature of this investigation, which due to its sensitive (and what would indisputably have been considered speculative) disposition, had to be kept confidential until the last conceivable moment. In this regard, my earnest thanks go to the following persons and organizations, viz: Fr Dr L Boyle and his magnificent staff at the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, the staff of the British Library, the Biblioteque Nation ale , the Hertziana Library, Ms M Eales, Mrs J Thomas, Mrs D Barnard, Mrs G Coleske and the other forbearing staff of the Port Elizabeth Technikon Library. I am also indebted to Mr DR Stirling (University of Port Elizabeth) and Mr S Kemball, for their assistance with certain optical calculations. My sincere thanks also go to Mr DJ Griffith (optical engineer) and Mr D van Staaden of the Division of Manufacturing and Aeronautical Systems Technology, CSIR in Pretoria for their indispensable contributions and recommendations. -

Le Père Emmanuel Faure (1880 - 1964)

Histoire Un pionnier du Linceul : Le Père Emmanuel Faure (1880 - 1964) par Pierre de Riedmatten Quel étonnant et difficile parcours que celui d’Emmanuel - Marie Faure ! 1 - D’abord un laïc, fortement engagé au service du Linceul Né en juin1880 dans le sud de la France, il fit des études importantes dans plusieurs domaines : homme de sciences, il fut médecin ; doué pour la peinture et la sculpture, il fut diplômé de l’École des Beaux-Arts (il fut membre de la Guilde des Artistes et fit du théâtre) ; très cultivé, il écrivit plusieurs livres, et fut membre du Syndicat des écrivains français et des publications chrétiennes. Marié au début du XXème siècle, il a eu trois enfants. Mais, très tôt, il est profondément marqué par la première photo du Linceul, faite par Secondo Pia en 1898. Dès 1905, il "s’occupe de la précieuse relique"1 ; il décide alors de consacrer sa vie à faire connaître et vénérer le Linceul, dont l’authenticité était pourtant "devenue insoutenable" pour le grand public, comme l’a rapporté Paul Vignon2. Il faut en effet se remettre dans le contexte d’abandon qui a suivi, très vite, l’enthousiasme extraordinaire provoqué par la révélation du négatif photographique. Dès 1900, le chanoine Ulysse Chevalier, très honorablement connu, publie son premier ouvrage3, niant totalement l’ancienneté du Saint Suaire : il y parle du fameux mémoire de Pierre 1 cf. lettre au chirurgien Pierre Barbet, en 1935. 2 cf. "Le Linceul du Christ - Étude scientifique", par Paul Vignon, docteur ès Sciences Naturelles - 1902 - éd. de Paris. 3 "Étude critique sur l’origine du Saint Suaire de Lirey - Chambéry - Turin", par U. -

As Provas Da Existência De Deus

Lucas Banzoli Emmanuel Dijon As Provas da Existência de Deus SUMÁRIO INTRODUÇÃO ......................................................................................................................... 5 CAP. 1 - EVIDÊNCIAS DA EXISTÊNCIA DE DEUS......................................................... 8 1º A Prova do Movimento ..................................................................................................... 8 2º A Causalidade Eficiente .................................................................................................. 10 3º Prova da Contingência .................................................................................................... 11 4º Prova da Perfeição ........................................................................................................... 13 5º Prova do governo do mundo ......................................................................................... 14 • O Argumento Teleológico ............................................................................................... 15 • Quem criou Deus? ............................................................................................................ 25 • O Argumento da Moralidade .......................................................................................... 28 CAP. 2 – A TEORIA DA EVOLUÇÃO ................................................................................ 32 • O Design Inteligente ........................................................................................................