"W. B. Townsend and the Struggle Against

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Garrison Life of the Mounted Soldier on the Great Plains

/7c GARRISON LIFE OF THE MOUNTED SOLDIER ON THE GREAT PLAINS, TEXAS, AND NEW MEXICO FRONTIERS, 1833-1861 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Stanley S. Graham, B. A. Denton, Texas August, 1969 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page MAPS ..................... .... iv Chapter I. THE REGIMENTS AND THE POSTS . .. 1 II. RECRUITMENT........... ........ 18 III. ROUTINE AT THE WESTERN POSTS ..0. 40 IV. RATIONS, CLOTHING, PROMOTIONS, PAY, AND CARE OF THE DISABLED...... .0.0.0.* 61 V. DISCIPLINE AND RELATED PROBLEMS .. 0 86 VI. ENTERTAINMENT, MORAL GUIDANCE, AND BURIAL OF THE FRONTIER..... 0. 0 . 0 .0 . 0. 109 VII. CONCLUSION.............. ...... 123 BIBLIOGRAPHY.......... .............. ....... ........ 126 iii LIST OF MAPS Figure Page 1. Forts West of the Mississippi in 1830 . .. ........ 15 2. Great Plains Troop Locations, 1837....... ............ 19 3. Great Plains, Texas, and New Mexico Troop Locations, 1848-1860............. ............. 20 4. Water Route to the West .......................... 37 iv CHAPTER I THE REGIMENTS AND THE POSTS The American cavalry, with a rich heritage of peacekeeping and combat action, depending upon the particular need in time, served the nation well as the most mobile armed force until the innovation of air power. In over a century of performance, the army branch adjusted to changing times and new technological advances from single-shot to multiple-shot hand weapons for a person on horseback, to rapid-fire rifles, and eventually to an even more mobile horseless, motor-mounted force. After that change, some Americans still longed for at least one regiment to be remounted on horses, as General John Knowles Herr, the last chief of cavalry in the United States Army, appealed in 1953. -

“Remarkable Stratagems and Conspiracies” : How Unscrupulous

“REMARKABLE STRATAGEMS AND CONSPIRACIES”: HOW UNSCRUPULOUS LAWYERS AND CREDULOUS JUDGES CREATED AN EXCEPTION TO THE HEARSAY RULE Marianne Wesson* This essay has a somewhat different goal than the other contributions to this Symposium: rather than considering present-day ethical predicaments, it aims to inspire reflection on an episode in which improper and unprofessional conduct by attorneys contributed to the creation of the law of evidence. In particular, it considers the events that led to the formulation and enactment of a rule that persistently affects the conduct of trials even by the most responsible and ethical lawyers: the hearsay exception codified as Federal Rule of Evidence 803(3).1 The bare bones of the narrative are well-known to nearly every lawyer, as it has formed a staple of the study of the law of evidence since the date of the U.S. Supreme Court’s first decision on the matter in 1892, in Mutual Life Insurance Company of New York v. Hillmon.2 Even the lay public was transfixed by the story in its time; the tale of John Hillmon was the subject * Marianne Wesson, Professor of Law, Wolf-Nichol Fellow, and President’s Teaching Scholar, University of Colorado School of Law. The author is grateful for the excellent research and editorial assistance of Andrea Viedt in the preparation of this essay. 1. The rule provides an exception to the general rule excluding hearsay for a statement of the declarant’s then existing state of mind, emotion, sensation, or physical condition (such as intent, plan, motive, design, mental feeling, pain, and bodily health), but not including a statement of memory or belief to prove the fact remembered or believed unless it relates to the execution, revocation, identification, or terms of declarant’s will. -

Reconstruction Report

RECONSTRUCTION IN AMERICA RECONSTRUCTION 122 Commerce Street Montgomery, Alabama 36104 334.269.1803 eji.org RECONSTRUCTION IN AMERICA Racial Violence after the Civil War, 1865-1876 © 2020 by Equal Justice Initiative. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, modified, or distributed in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means without express prior written permission of Equal Justice Initiative. RECONSTRUCTION IN AMERICA Racial Violence after the Civil War, 1865-1876 The Memorial at the EJI Legacy Pavilion in Montgomery, Alabama. (Mickey Welsh/Montgomery Advertiser) 5 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 6 THE DANGER OF FREEDOM 56 Political Violence 58 Economic Intimidation 63 JOURNEY TO FREEDOM 8 Enforcing the Racial Social Order 68 Emancipation and Citizenship Organized Terror and Community Massacres 73 Inequality After Enslavement 11 Accusations of Crime 76 Emancipation by Proclamation—Then by Law 14 Arbitrary and Random Violence 78 FREEDOM TO FEAR 22 RECONSTRUCTION’S END 82 A Terrifying and Deadly Backlash Reconstruction vs. Southern Redemption 84 Black Political Mobilization and White Backlash 28 Judicial and Political Abandonment 86 Fighting for Education 32 Redemption Wins 89 Resisting Economic Exploitation 34 A Vanishing Hope 93 DOCUMENTING RECONSTRUCTION 42 A TRUTH THAT NEEDS TELLING 96 VIOLENCE Known and Unknown Horrors Notes 106 Acknowledgments 119 34 Documented Mass Lynchings During the Reconstruction Era 48 Racial Terror and Reconstruction: A State Snapshot 52 7 INTRODUCTION Thousands more were assaulted, raped, or in- jured in racial terror attacks between 1865 and 1876. The rate of documented racial terror lynchings during Reconstruction is nearly three In 1865, after two and a half centuries of brutal white mobs and individuals who were shielded It was during Reconstruction that a times greater than during the era we reported enslavement, Black Americans had great hope from arrest and prosecution. -

Newspaper Distribution List

Newspaper Distribution List The following is a list of the key newspaper distribution points covering our Integrated Media Pro and Mass Media Visibility distribution package. Abbeville Herald Little Elm Journal Abbeville Meridional Little Falls Evening Times Aberdeen Times Littleton Courier Abilene Reflector Chronicle Littleton Observer Abilene Reporter News Livermore Independent Abingdon Argus-Sentinel Livingston County Daily Press & Argus Abington Mariner Livingston Parish News Ackley World Journal Livonia Observer Action Detroit Llano County Journal Acton Beacon Llano News Ada Herald Lock Haven Express Adair News Locust Weekly Post Adair Progress Lodi News Sentinel Adams County Free Press Logan Banner Adams County Record Logan Daily News Addison County Independent Logan Herald Journal Adelante Valle Logan Herald-Observer Adirondack Daily Enterprise Logan Republican Adrian Daily Telegram London Sentinel Echo Adrian Journal Lone Peak Lookout Advance of Bucks County Lone Tree Reporter Advance Yeoman Long Island Business News Advertiser News Long Island Press African American News and Issues Long Prairie Leader Afton Star Enterprise Longmont Daily Times Call Ahora News Reno Longview News Journal Ahwatukee Foothills News Lonoke Democrat Aiken Standard Loomis News Aim Jefferson Lorain Morning Journal Aim Sussex County Los Alamos Monitor Ajo Copper News Los Altos Town Crier Akron Beacon Journal Los Angeles Business Journal Akron Bugle Los Angeles Downtown News Akron News Reporter Los Angeles Loyolan Page | 1 Al Dia de Dallas Los Angeles Times -

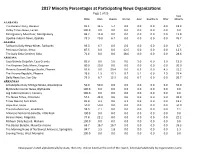

Minority Percentages at Participating News Organizations

Minority Percentages at Participating News Organizations Asian Native Asian Native American Black Hispanic American Total American Black Hispanic American Total ALABAMA Paragould Daily Press 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Anniston Star 0.0 7.7 0.0 0.0 7.7 Pine Bluff Commercial 0.0 13.3 0.0 0.0 13.3 The Birmingham News 0.8 18.3 0.0 0.0 19.2 The Courier, Russellville 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Decatur Daily 0.0 7.1 3.6 0.0 10.7 Northwest Arkansas Newspapers LLC, Springdale 0.0 1.5 1.5 0.0 3.0 Enterprise Ledger 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Stuttgart Daily Leader 0.0 0.0 20.0 0.0 20.0 TimesDaily, Florence 0.0 2.9 0.0 0.0 2.9 Evening Times, West Memphis 0.0 25.0 0.0 0.0 25.0 The Gadsden Times 0.0 5.6 0.0 0.0 5.6 CALIFORNIA The Daily Mountain Eagle, Jasper 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Desert Dispatch, Barstow 14.3 0.0 0.0 0.0 14.3 Valley Times-News, Lanett 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Center for Investigative Reporting, Berkeley 7.1 14.3 14.3 0.0 35.7 Press-Register, Mobile 0.0 10.5 0.0 0.0 10.5 Ventura County Star, Camarillo 1.6 3.3 16.4 0.0 21.3 Montgomery Advertiser 0.0 19.5 2.4 0.0 22.0 Chico Enterprise-Record 3.6 0.0 0.0 0.0 3.6 The Daily Sentinel, Scottsboro 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Daily Triplicate, Crescent City 11.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 11.1 The Tuscaloosa News 5.1 2.6 0.0 0.0 7.7 The Davis Enterprise 7.1 0.0 7.1 0.0 14.3 ALASKA Imperial Valley Press, El Centro 17.6 0.0 41.2 0.0 58.8 Fairbanks Daily News-Miner 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 North County Times, Escondido 1.3 0.0 5.2 0.0 6.5 Peninsula Clarion, Kenai 0.0 10.0 0.0 0.0 10.0 The Fresno Bee 6.4 1.3 16.7 0.0 24.4 The Daily News, Ketchikan -

Kpanews (SITEBUILDER)

Kansas Press Association Return to Menu KDAN Network Participants NEWSPAPER CITY COUNTY CIRC NEWSPAPER CITY COUNTY CIRC Dodge City Daily Globe Dodge City Ford 6,691 Galena Sentinel-Times Galena Cherokee 1,274 Garden City Telegram Garden City Finney 7,924 Anderson County Review Garnett Anderson 2,924 Larned Tiller & Toiler Larned Pawnee 1,609 Hanover News Hanover Washington 866 Lawrence Journal-World Lawrence Douglas 18,651 Haskell County Monitor-Chief Sublette Haskell 729 Manhattan Mercury Manhattan Riley 9,504 Herington Times Herington Dickinson 1,933 Augusta Daily Gazette Augusta Butler 1,907 Hesston Record Hesston Harvey 1,065 Newton Kansan Newton Harvey 7,074 Hill City Times Hill City Graham 2,250 Great Bend Tribune Great Bend Barton 6,250 Hoisington Dispatch Hoisington Barton 1,326 Wellington News Wellington Sumner 2,293 Holton Recorder Holton Jackson 4,575 Winfield Daily Courier Winfield Cowley 5,480 Horton Headlight Horton Brown 1,367 Prairie Post White City Morris 849 Iola Register Iola Allen 3,785 Caldwell Messenger Caldwell Sumner 1,222 Jewell County Record Mankato Jewell 911 Eureka Herald Eureka Greenwood 2,071 Johnson Pioneer Johnson Stanton 800 Ark Valley News Valley Center Sedgwick 1,836 Junction City Daily Union Junction City Geary 4,538 Arkansas City Traveler Arkansas City Cowley 4,045 Edwards County Sentinel Kinsley Edwards 1,012 Basehor Sentinel Basehor Leavenworth 1,078 Kiowa County Signal Greensburg Kiowa 966 Belleville Telescope Belleville Republic 2,778 Leavenworth Times Leavenworth Leavenworth 5,531 Beloit Call Beloit -

![Leavenworth, KS] Daily Times, March 26, 1864-November 11, 1864 Vicki Betts University of Texas at Tyler, Vbetts@Uttyler.Edu](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9086/leavenworth-ks-daily-times-march-26-1864-november-11-1864-vicki-betts-university-of-texas-at-tyler-vbetts-uttyler-edu-2179086.webp)

Leavenworth, KS] Daily Times, March 26, 1864-November 11, 1864 Vicki Betts University of Texas at Tyler, [email protected]

University of Texas at Tyler Scholar Works at UT Tyler By Title Civil War Newspapers 2016 [Leavenworth, KS] Daily Times, March 26, 1864-November 11, 1864 Vicki Betts University of Texas at Tyler, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uttyler.edu/cw_newstitles Recommended Citation Betts, ickV i, "[Leavenworth, KS] Daily Times, March 26, 1864-November 11, 1864" (2016). By Title. Paper 47. http://hdl.handle.net/10950/709 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Civil War Newspapers at Scholar Works at UT Tyler. It has been accepted for inclusion in By Title by an authorized administrator of Scholar Works at UT Tyler. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DAILY TIMES [LEAVENWORTH, KS] March 26, 1864 – November 11, 1864 DAILY TIMES [LEAVENWORTH, KS], March 26, 1864, p. 2, c. 4 Correspondence of the Times. Fort Smith, Ark., March 7th, 1864. Spring is now at hand and the military is beginning to show considerable signs of activity. Gen. Thayer has moved nearly all the troops out of the town, and is having the place thoroughly cleansed. He is also erecting suitable fortifications for the defense of the place by a small force, when the grand move on Texas is made, which nearly all the soldiers will hail with delight, as they look on the conquest of that State as virtually ending the war west of the Mississippi. There are about 900 men at this place who have taken the prescribed oath preparatory to voting next Monday. A great many of them are not of the purest water, but would turn every day to be at the top of the pile. -

December 4, 2017 the Hon. Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary United States Department of Commerce 1401 Constitution Avenue, NW Washi

December 4, 2017 The Hon. Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary United States Department of Commerce 1401 Constitution Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20230 Re: Uncoated Groundwood Paper from Canada, Inv. Nos. C–122–862 and A-122-861 Dear Secretary Ross: On behalf of the thousands of employees working at the more than 1,100 newspapers that we publish in cities and towns across the United States, we urge you to heavily scrutinize the antidumping and countervailing duty petitions filed by North Pacific Paper Company (NORPAC) regarding uncoated groundwood paper from Canada, the paper used in newspaper production. We believe that these cases do not warrant the imposition of duties, which would have a very severe impact on our industry and many communities across the United States. NORPAC’s petitions are based on incorrect assessments of a changing market, and appear to be driven by the short-term investment strategies of the company’s hedge fund owners. The stated objectives of the petitions are flatly inconsistent with the views of the broader paper industry in the United States. The print newspaper industry has experienced an unprecedented decline for more than a decade as readers switch to digital media. Print subscriptions have declined more than 30 percent in the last ten years. Although newspapers have successfully increased digital readership, online advertising has proven to be much less lucrative than print advertising. As a result, newspapers have struggled to replace print revenue with online revenue, and print advertising continues to be the primary revenue source for local journalism. If Canadian imports of uncoated groundwood paper are subject to duties, prices in the whole newsprint market will be shocked and our supply chains will suffer. -

Kansas Newspaper Archive

GenealogyBank.com genealogybank.com/gbnk/newspapers/Kansas-newspaper-list/ List of Kansas Newspapers Cit y Tit le Date Range Collect ion Abilene Abilene Reflector- Chronicle 12/17/1999 – 12/14/2012 Recent Obituaries Atchison Weekly Champion and Press 2/20/1858 – 5/22/1869 Newspaper Archives Atchison Atchison Blade 7/23/1892 – 1/20/1894 Newspaper Archives Augusta Augusta Daily Gazette 2/12/2001 – 8/13/2012 Recent Obituaries Baxter Springs Southern Argus 6/18/1891 – 2/4/1892 Newspaper Archives Cedar Vale Progressive Communist 1/1/1875 – 12/1/1875 Newspaper Archives Chanute Chanute Tribune 3/27/1998 – Current Recent Obituaries Cherokee Kansas Homestead 12/23/1899 – 1/6/1900 Newspaper Archives Coffeyville Afro-American Advocate 9/2/1891 – 9/1/1893 Newspaper Archives Coffeyville Vindicator 12/17/1904 – 2/9/1906 Newspaper Archives Coffeyville American 4/23/1898 – 4/1/1899 Newspaper Archives Coffeyville Kansas Blackman 4/20/1894 – 6/29/1894 Newspaper Archives Coffeyville Coffeyville Herald 3/21/1908 – 6/13/1908 Newspaper Archives Columbus Cherokee County News- Advocate 12/24/2008 – Current Recent Obituaries Derby Derby Reporter 9/6/2000 – 12/30/2008 Recent Obituaries Dodge City Dodge City Daily Globe 8/9/2005 – Current Recent Obituaries El Dorado El Dorado Times 7/9/2001 – Current Recent Obituaries El Dorado Butler County Times- Gazette 11/5/2013 – Current Recent Obituaries Emporia Emporia Gazette 4/1/1896 – 3/17/1921 Newspaper Archives Emporia Emporia Citizen 3/1/1932 – 11/1/1932 Newspaper Archives Emporia Emporia Gazette 4/1/2002 – Current -

Diamond Dick” Mcclellan

George B. “Diamond Dick” McClellan 2KANSAS HISTORY DOCTOR DIAMOND DICK Leavenworth’s Flamboyant Medicine Man by L. Boyd Finch ansas was the stage on which a remarkable Evidence of his expertise in self-promotion is found in Victorian-era character strutted for nearly a Wisconsin, Iowa, and Nebraska, as well as in Kansas. Mc- third of a century. George B. McClellan was Clellan enjoyed particular success in Leavenworth in equally at ease in small midwestern cities and 1887–1888. His promotional methods there were memo- K towns, and in the salons of St. Louis and Den- rable; in reporting his accidental death many years later, the ver. He knew the inside of a jail as well as the plush ac- Leavenworth Times did not mention McClellan’s medicines commodations of a private railroad car. One newspaper or his healing techniques; instead, it was his methods of at- writer labeled him “a long-haired quack,” another praised tracting patients that were recounted.2 him for “such wonderful cures in this city and surround- On December 14, 1911, the Kansas City Journal fairly ing country.” He was an itinerant peddler of questionable shouted: “DIAMOND DICK IS DEAD/Picturesque Kansas medical cures, one of hundreds of pitchmen (and a few Character Succumbs to Ry. Accident.” The paper reported: women) who crisscrossed America, usually living on the fringes of society, going wherever they could find cus- George B. McClellan, who advertised himself as “Doc- tomers. Most hawked nostrums with unique names: Indi- tor Diamond Dick” and who was known in every an Sagwa, Seminole Cough Balm, Hindoo Patalka, Ka- Kansas hamlet by his costume, which was copied from that worn by the hero of the old-time “dime Ton-Ka, Modoc Indian Oil. -

2017 Summary Report for Each News Organization.Xlsx

2017 Minority Percentages at Participating News Organizations Page 1 of 25 Total White Black Hispanic Am. Ind. Asian Haw/Pac. Is Other Minority ALABAMA The Decatur Daily, Decatur 81.1 13.5 5.4 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 18.9 Valley Times-News, Lanett 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Montgomery Advertiser, Montgomery 84.2 15.8 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 15.8 Opelika-Auburn News, Opelika 73.3 20.0 6.7 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 26.7 ALASKA Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, Fairbanks 93.3 6.7 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 6.7 Peninsula Clarion, Kenai 87.5 0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 0.0 0.0 12.5 The Daily Sitka Sentinel, Sitka 71.4 0.0 0.0 28.6 0.0 0.0 0.0 28.6 ARIZONA Casa Grande Dispatch, Casa Grande 85.0 0.0 5.0 0.0 5.0 0.0 5.0 15.0 The Kingman Daily Miner, Kingman 80.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Phoenix Gannett Design Studio, Phoenix 65.6 0.0 20.4 0.0 6.5 0.0 4.3 31.2 The Arizona Republic, Phoenix 76.6 1.5 13.1 0.7 5.1 0.0 2.9 23.4 Daily News-Sun, Sun City 73.3 6.7 13.3 0.0 6.7 0.0 0.0 26.7 ARKANSAS Arkadelphia Daily Siftings Herald, Arkadelphia 50.0 50.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 50.0 Blytheville Courier News, Blytheville 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Log Cabin Democrat, Conway 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The News-Times, El Dorado 57.1 42.9 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 42.9 Times Record, Fort Smith 81.8 9.1 0.0 9.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 18.2 Hope Star, Hope 50.0 50.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 50.0 The Jonesboro Sun, Jonesboro 92.9 7.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 7.1 Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Little Rock 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Banner-News, Magnolia 77.8 22.2 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 22.2 Malvern Daily Record, Malvern 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Baxter Bulletin, Mountain Home 66.7 16.7 16.7 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 33.3 The Morning News of Northwest Arkansas, Springdale 94.7 3.5 1.8 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 5.3 Evening Times, West Memphis 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Newspapers listed alphabetically by state, then city. -

Communications and Information

Communications and Information Communications Communications Information and Kansas Statistical Abstract 2020 Institute for Policy & Social Research ipsr.ku.edu/ksdata/ksah/ September 2021 Digital TV Licensees in Kansas with Tower Locations KSNB-TV Cheyenne Nemaha Brown Rawlins Norton Phillips Smith Jewell Washington Marshall KSNK Doniphan KQTV Republic Atchison Decatur Cloud Sherman Jackson Thomas Sheridan Graham Rooks Osborne Mitchell Clay Pottawatomie KBSL-DT Riley KTWU Leavenworth KTMJ-CD WDAF-TV KSNT KCTV KMBC-TV Ottawa KSMO-TV KWKS KTKA-TV Wyandotte Lincoln Jefferson KCPT Wallace Logan Gove Trego Ellis Russell KAAS-TV Geary KSQA KCWE Dickinson WIBW-TV Johnson KBSH-DT Shawnee KPXE-TV Saline KMCI-TV Wabaunsee KSHB-TV Morris Osage Douglas KTAJ-TV KOOD Miami Lyon Franklin KMCI-TV Greeley Wichita Scott Lane Ness Rush KOCW Ellsworth McPherson Marion Chase Coffey KSNC Anderson Linn Pawnee Barton Hamilton Kearny Finney Hodgeman Stafford Rice Reno Harvey Greenwood KPTS KMTW Butler Woodson Allen Bourbon Gray Edwards KSCW-DT KSNG KWCH-DT KAKE KSWK KDCK Pratt KGPT-CD KSAS-TV Stanton Grant Wilson Neosho Kiowa Kingman KDCU-DT Crawford KUPK KBSD-DT KSNW Elk Ford Sedgwick Haskell Meade Clark Barber Sumner Cowley Morton Stevens Labette Seward Comanche Harper KFJX Chautauqua Montgomery KOAM-TV KOZJ Cherokee KODE-TV KSNF Source: Institute for Policy & Social Research, The University of Kansas; data from Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Digital TV Tower Tower symbol represents the approximate location of one or more towers. (as of July 1, 2021)