Molecular Mechanisms of Bacterial Bioluminescence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

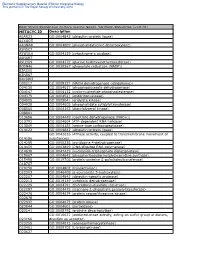

METACYC ID Description A0AR23 GO:0004842 (Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Integrative Biology This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012 Heat Stress Responsive Zostera marina Genes, Southern Population (α=0. -

Ferric Reductase Activity of the Arsh Protein from Acidithiobacillus Ferrooxidans

J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. (2011), 21(5), 464–469 doi: 10.4014/jmb.1101.01020 First published online 13 April 2011 Ferric Reductase Activity of the ArsH Protein from Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans Mo, Hongyu1,2, Qian Chen1,2, Juan Du1, Lin Tang1, Fang Qin1, Bo Miao2, Xueling Wu2, and Jia Zeng1,2* 1College of Biology, Hunan University, Changsha, Hunan 410082, P. R. China 2Department of Bioengineering, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan 410083, P. R. China Received: January 14, 2011 / Revised: March 10, 2011 / Accepted: March 11, 2011 The arsH gene is one of the arsenic resistance system in iron (free or chelated) into ferrous iron before its incorporation bacteria and eukaryotes. The ArsH protein was annotated into heme and nonheme iron-containing proteins. Ferric as a NADPH-dependent flavin mononucleotide (FMN) reductase catalyzes the reduction of complexed Fe3+ to reductase with unknown biological function. Here we complexed Fe2+ using NAD(P)H as the electron donor. The report for the first time that the ArsH protein showed resulting Fe2+ is subsequently released and incorporated high ferric reductase activity. Glu104 was an essential into iron-containing proteins [17]. residue for maintaining the stability of the FMN cofactor. Here we report for the first time that the ArsH protein The ArsH protein may perform an important role for showed high ferric reduction activity. The ArsH from A. cytosolic ferric iron assimilation in vivo. ferrooxidans may perform an important role as a NADPH- Keywords: Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, ArsH, flavoprotein, dependent ferric reductase for cytosolic ferric iron assimilation ferric reductase in vivo. MATERIALS AND METHODS Arsenic resistance genes are widespread in nature. -

Biochemical and Biophysical Characterisation of Anopheles Gambiae Nadph-Cytochrome P450 Reductase

BIOCHEMICAL AND BIOPHYSICAL CHARACTERISATION OF ANOPHELES GAMBIAE NADPH-CYTOCHROME P450 REDUCTASE Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by PHILIP WIDDOWSON SEPTEMBER 2010 0 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are a number of people whom I would like to thank for their support during the completion of this thesis. Firstly, I would like to thank my family; Mum, Louise and Chris for putting up with me over the years and for their love, patience and, in particular to Chris, technical support throughout– I could not have coped on my own without all your help. I would like to extend special thanks to Professor Lu-Yun Lian for her constant supervision throughout my Ph.D. She always kept me on the right path and was always available for support and advice which was especially useful when things were not going to plan. Thank you for all your help. In addition to Professor Lian I would like to thank all the members of the Structural Biology Group and everybody, past and present, whom I worked alongside in Lab C over the past four years. I would also like to thank the University of Liverpool for the funding that made all this possible. I would like to make particular mention to a few people in the School of Biological Sciences who were of particular help during my time at university. Dr. Mark Wilkinson was a constant support, not only during my Ph.D, but as my undergraduate tutor and honours project supervisor. Dr. Dan Rigden and Dr. -

Single-Molecule Spectroscopy Reveals How Calmodulin Activates NO Synthase by Controlling Its Conformational Fluctuation Dynamics

Single-molecule spectroscopy reveals how calmodulin activates NO synthase by controlling its conformational fluctuation dynamics Yufan Hea,1, Mohammad Mahfuzul Haqueb,1, Dennis J. Stuehrb,2, and H. Peter Lua,2 aCenter for Photochemical Sciences, Department of Chemistry, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH 43403; and bDepartment of Pathobiology, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195 Edited by Louis J. Ignarro, University of California, Los Angeles School of Medicine, Beverly Hills, CA, and approved July 31, 2015 (received for review May 5, 2015) Mechanisms that regulate the nitric oxide synthase enzymes (NOS) this model, the FMN domain is suggested to be highly dynamic are of interest in biology and medicine. Although NOS catalysis and flexible due to a connecting hinge that allows it to alternate relies on domain motions, and is activated by calmodulin binding, between its electron-accepting (FAD→FMN) or closed confor- the relationships are unclear. We used single-molecule fluores- mation and electron-donating (FMN→heme) or open conforma- cence resonance energy transfer (FRET) spectroscopy to elucidate tion (Fig. 1 A and B)(28,30–36). In the electron-accepting closed the conformational states distribution and associated conforma- conformation, the FMN domain interacts with the NADPH/FAD tional fluctuation dynamics of the two electron transfer domains domain (FNR domain) to receive electrons, whereas in the elec- in a FRET dye-labeled neuronal NOS reductase domain, and to tron donating open conformation the FMN domain has moved understand how calmodulin affects the dynamics to regulate away to expose the bound FMN cofactor so that it may transfer catalysis. -

![View, the Catalytic Center of Bnoss Is Almost Identical to Mnos Except That a Conserved Val Near Heme Iron in Mnos Is Substituted by Iie[25]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8837/view-the-catalytic-center-of-bnoss-is-almost-identical-to-mnos-except-that-a-conserved-val-near-heme-iron-in-mnos-is-substituted-by-iie-25-78837.webp)

View, the Catalytic Center of Bnoss Is Almost Identical to Mnos Except That a Conserved Val Near Heme Iron in Mnos Is Substituted by Iie[25]

STUDY OF ELECTRON TRANSFER THROUGH THE REDUCTASE DOMAIN OF NEURONAL NITRIC OXIDE SYNTHASE AND DEVELOPMENT OF BACTERIAL NITRIC OXIDE SYNTHASE INHIBITORS YUE DAI Bachelor of Science in Chemistry Wuhan University June 2008 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN CLINICAL AND BIOANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY July 2016 We hereby approve this dissertation for Yue Dai Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy in Clinical-Bioanalytical Chemistry Degree for the Department of Chemistry and CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY’S College of Graduate Studies by Dennis J. Stuehr. PhD. Department of Pathobiology, Cleveland Clinic / July 8th 2016 Mekki Bayachou. PhD. Department of Chemistry / July 8th 2016 Thomas M. McIntyre. PhD. Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Cleveland Clinic / July 8th 2016 Bin Su. PhD. Department of Chemistry / July 8th 2016 Jun Qin. PhD. Department of Molecular Cardiology, Cleveland Clinic / July 8th 2016 Student’s Date of Defense: July 8th 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First I would like to express my special appreciation and thanks to my Ph. D. mentor, Dr. Dennis Stuehr. You have been a tremendous mentor for me. It is your constant patience, encouraging and support that guided me on the road of becoming a research scientist. Your advices on both research and life have been priceless for me. I would like to thank my committee members - Professor Mekki Bayachou, Professor Bin Su, Dr. Thomas McIntyre, Dr. Jun Qin and my previous committee members - Dr. Donald Jacobsen and Dr. Saurav Misra for sharing brilliant comments and suggestions with me. I would like to thank all our lab members for their help ever since I joint our lab. -

Cbic.202000100Taverne

Delft University of Technology A Minimized Chemoenzymatic Cascade for Bacterial Luciferase in Bioreporter Applications Phonbuppha, Jittima; Tinikul, Ruchanok; Wongnate, Thanyaporn; Intasian, Pattarawan; Hollmann, Frank; Paul, Caroline E.; Chaiyen, Pimchai DOI 10.1002/cbic.202000100 Publication date 2020 Document Version Final published version Published in ChemBioChem Citation (APA) Phonbuppha, J., Tinikul, R., Wongnate, T., Intasian, P., Hollmann, F., Paul, C. E., & Chaiyen, P. (2020). A Minimized Chemoenzymatic Cascade for Bacterial Luciferase in Bioreporter Applications. ChemBioChem, 21(14), 2073-2079. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbic.202000100 Important note To cite this publication, please use the final published version (if applicable). Please check the document version above. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download, forward or distribute the text or part of it, without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license such as Creative Commons. Takedown policy Please contact us and provide details if you believe this document breaches copyrights. We will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. This work is downloaded from Delft University of Technology. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to a maximum of 10. Green Open Access added to TU Delft Institutional Repository ‘You share, we take care!’ – Taverne project https://www.openaccess.nl/en/you-share-we-take-care Otherwise as indicated in the copyright section: the publisher is the copyright holder of this work and the author uses the Dutch legislation to make this work public. -

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSCRIPTOME, PROTEOME AND miRNA PROFILE OF KUPFFER CELLS AND MONOCYTES Andrey Elchaninov1,3*, Anastasiya Lokhonina1,3, Maria Nikitina2, Polina Vishnyakova1,3, Andrey Makarov1, Irina Arutyunyan1, Anastasiya Poltavets1, Evgeniya Kananykhina2, Sergey Kovalchuk4, Evgeny Karpulevich5,6, Galina Bolshakova2, Gennady Sukhikh1, Timur Fatkhudinov2,3 1 Laboratory of Regenerative Medicine, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology Named after Academician V.I. Kulakov of Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia 2 Laboratory of Growth and Development, Scientific Research Institute of Human Morphology, Moscow, Russia 3 Histology Department, Medical Institute, Peoples' Friendship University of Russia, Moscow, Russia 4 Laboratory of Bioinformatic methods for Combinatorial Chemistry and Biology, Shemyakin-Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 5 Information Systems Department, Ivannikov Institute for System Programming of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 6 Genome Engineering Laboratory, Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Dolgoprudny, Moscow Region, Russia Figure S1. Flow cytometry analysis of unsorted blood sample. Representative forward, side scattering and histogram are shown. The proportions of negative cells were determined in relation to the isotype controls. The percentages of positive cells are indicated. The blue curve corresponds to the isotype control. Figure S2. Flow cytometry analysis of unsorted liver stromal cells. Representative forward, side scattering and histogram are shown. The proportions of negative cells were determined in relation to the isotype controls. The percentages of positive cells are indicated. The blue curve corresponds to the isotype control. Figure S3. MiRNAs expression analysis in monocytes and Kupffer cells. Full-length of heatmaps are presented. -

Generate Metabolic Map Poster

Authors: Pallavi Subhraveti Anamika Kothari Quang Ong Ron Caspi An online version of this diagram is available at BioCyc.org. Biosynthetic pathways are positioned in the left of the cytoplasm, degradative pathways on the right, and reactions not assigned to any pathway are in the far right of the cytoplasm. Transporters and membrane proteins are shown on the membrane. Ingrid Keseler Peter D Karp Periplasmic (where appropriate) and extracellular reactions and proteins may also be shown. Pathways are colored according to their cellular function. Csac1394711Cyc: Candidatus Saccharibacteria bacterium RAAC3_TM7_1 Cellular Overview Connections between pathways are omitted for legibility. Tim Holland TM7C00001G0420 TM7C00001G0109 TM7C00001G0953 TM7C00001G0666 TM7C00001G0203 TM7C00001G0886 TM7C00001G0113 TM7C00001G0247 TM7C00001G0735 TM7C00001G0001 TM7C00001G0509 TM7C00001G0264 TM7C00001G0176 TM7C00001G0342 TM7C00001G0055 TM7C00001G0120 TM7C00001G0642 TM7C00001G0837 TM7C00001G0101 TM7C00001G0559 TM7C00001G0810 TM7C00001G0656 TM7C00001G0180 TM7C00001G0742 TM7C00001G0128 TM7C00001G0831 TM7C00001G0517 TM7C00001G0238 TM7C00001G0079 TM7C00001G0111 TM7C00001G0961 TM7C00001G0743 TM7C00001G0893 TM7C00001G0630 TM7C00001G0360 TM7C00001G0616 TM7C00001G0162 TM7C00001G0006 TM7C00001G0365 TM7C00001G0596 TM7C00001G0141 TM7C00001G0689 TM7C00001G0273 TM7C00001G0126 TM7C00001G0717 TM7C00001G0110 TM7C00001G0278 TM7C00001G0734 TM7C00001G0444 TM7C00001G0019 TM7C00001G0381 TM7C00001G0874 TM7C00001G0318 TM7C00001G0451 TM7C00001G0306 TM7C00001G0928 TM7C00001G0622 TM7C00001G0150 TM7C00001G0439 TM7C00001G0233 TM7C00001G0462 TM7C00001G0421 TM7C00001G0220 TM7C00001G0276 TM7C00001G0054 TM7C00001G0419 TM7C00001G0252 TM7C00001G0592 TM7C00001G0628 TM7C00001G0200 TM7C00001G0709 TM7C00001G0025 TM7C00001G0846 TM7C00001G0163 TM7C00001G0142 TM7C00001G0895 TM7C00001G0930 Detoxification Carbohydrate Biosynthesis DNA combined with a 2'- di-trans,octa-cis a 2'- Amino Acid Degradation an L-methionyl- TM7C00001G0190 superpathway of pyrimidine deoxyribonucleotides de novo biosynthesis (E. -

The Human Flavoproteome

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 535 (2013) 150–162 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yabbi Review The human flavoproteome ⇑ Wolf-Dieter Lienhart, Venugopal Gudipati, Peter Macheroux Graz University of Technology, Institute of Biochemistry, Petersgasse 12, A-8010 Graz, Austria article info abstract Article history: Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) is an essential dietary compound used for the enzymatic biosynthesis of FMN and Received 17 December 2012 FAD. The human genome contains 90 genes encoding for flavin-dependent proteins, six for riboflavin and in revised form 21 February 2013 uptake and transformation into the active coenzymes FMN and FAD as well as two for the reduction to Available online 15 March 2013 the dihydroflavin form. Flavoproteins utilize either FMN (16%) or FAD (84%) while five human flavoen- zymes have a requirement for both FMN and FAD. The majority of flavin-dependent enzymes catalyze Keywords: oxidation–reduction processes in primary metabolic pathways such as the citric acid cycle, b-oxidation Coenzyme A and degradation of amino acids. Ten flavoproteins occur as isozymes and assume special functions in Coenzyme Q the human organism. Two thirds of flavin-dependent proteins are associated with disorders caused by Folate Heme allelic variants affecting protein function. Flavin-dependent proteins also play an important role in the Pyridoxal 50-phosphate biosynthesis of other essential cofactors and hormones such as coenzyme A, coenzyme Q, heme, pyri- Steroids doxal 50-phosphate, steroids and thyroxine. Moreover, they are important for the regulation of folate Thyroxine metabolites by using tetrahydrofolate as cosubstrate in choline degradation, reduction of N-5.10-meth- Vitamins ylenetetrahydrofolate to N-5-methyltetrahydrofolate and maintenance of the catalytically competent form of methionine synthase. -

Reaction Mechanism of Azoreductases Suggests Convergent Evolution with Quinone Oxidoreductases

Protein Cell 2010, 1(8): 780–790 Protein & Cell DOI 10.1007/s13238-010-0090-2 RESEARCH ARTICLE Reaction mechanism of azoreductases suggests convergent evolution with quinone oxidoreductases ✉ Ali Ryan*, Chan-Ju Wang*, Nicola Laurieri*, Isaac Westwood, Edith Sim Department of Pharmacology, University of Oxford, Mansfield Road, Oxford, OX1 3QT, UK ✉ Correspondence: [email protected] Received June 2, 2010 Accepted June 28, 2010 ABSTRACT the dye used for dying fabrics does not bind to the fabric, and as a result, is lost in the effluent (Shore, 1995). As these dyes Azoreductases are involved in the bioremediation by can be carcinogenic (Alves de Lima et al., 2007) their removal bacteria of azo dyes found in waste water. In the gut flora, from the effluent is essential. This has driven investigations they activate azo pro-drugs, which are used for treatment into both electrochemical reduction of azo dyes (Wang et al., of inflammatory bowel disease, releasing the active 2010b), as well as the use of both aerobic and anaerobic component 5-aminosalycilic acid. The bacterium bacteria for bioremediation (dos Santos et al., 2007; You et P. aeruginosa has three azoreductase genes, paAzoR1, al., 2007). paAzoR2 and paAzoR3, which as recombinant enzymes Azo bonds are also found in some drugs including those have been shown to have different substrate specifici- used for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). ties. The mechanism of azoreduction relies upon tauto- Azo compounds have also been shown to be effective merisation of the substrate to the hydrazone form. We antibacterial (Farghaly and Abdalla, 2009) and antitumor (El- report here the characterization of the P. -

Q 297 Suppl USE

The following supplement accompanies the article Atlantic salmon raised with diets low in long-chain polyunsaturated n-3 fatty acids in freshwater have a Mycoplasma dominated gut microbiota at sea Yang Jin, Inga Leena Angell, Simen Rød Sandve, Lars Gustav Snipen, Yngvar Olsen, Knut Rudi* *Corresponding author: [email protected] Aquaculture Environment Interactions 11: 31–39 (2019) Table S1. Composition of high- and low LC-PUFA diets. Stage Fresh water Sea water Feed type High LC-PUFA Low LC-PUFA Fish oil Initial fish weight (g) 0.2 0.4 1 5 15 30 50 0.2 0.4 1 5 15 30 50 80 200 Feed size (mm) 0.6 0.9 1.3 1.7 2.2 2.8 3.5 0.6 0.9 1.3 1.7 2.2 2.8 3.5 3.5 4.9 North Atlantic fishmeal (%) 41 40 40 40 40 30 30 41 40 40 40 40 30 30 35 25 Plant meals (%) 46 45 45 42 40 49 48 46 45 45 42 40 49 48 39 46 Additives (%) 3.3 3.2 3.2 3.5 3.3 3.4 3.9 3.3 3.2 3.2 3.5 3.3 3.4 3.9 2.6 3.3 North Atlantic fish oil (%) 9.9 12 12 15 16 17 18 0 0 0 0 0 1.2 1.2 23 26 Linseed oil (%) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 6.8 8.1 8.1 9.7 11 10 11 0 0 Palm oil (%) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3.2 3.8 3.8 5.4 5.9 5.8 5.9 0 0 Protein (%) 56 55 55 51 49 47 47 56 55 55 51 49 47 47 44 41 Fat (%) 16 18 18 21 22 22 22 16 18 18 21 22 22 22 28 31 EPA+DHA (% diet) 2.2 2.4 2.4 2.9 3.1 3.1 3.1 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 4 4.2 Table S2. -

Probing the Flavin Transfer Mechanism in Alkanesulfonate Monooxygenase System

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/433839; this version posted October 2, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Probing the flavin transfer mechanism in alkanesulfonate monooxygenase system Dayal PV and Ellis HR Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Auburn University, Alabama, 36849 Email: [email protected] Abstract Bacteria acquire sulfur through the sulfur assimilation pathway, but under sulfur limiting conditions bacteria must acquire sulfur from alternative sources. The alkanesulfonate monooxygenase enzymes are expressed under sulfur-limiting conditions, and catalyze the desulfonation of wide-range of alkanesulfonate substrates. The SsuE enzyme is an NADPH-dependent FMN reductase that provides reduced flavin to the SsuD monooxygenase. The mechanism for the transfer of reduced flavin in flavin dependent two-component systems occurs either by free- diffusion or channeling. Previous studies have shown the presence of protein-protein interactions between SsuE and SsuD, but the identification of putative interaction sights have not been investigated. Current studies utilized HDX-MS to identify protective sites on SsuE and SsuD. A conserved α-helix on SsuD showed a decrease in percent deuteration when SsuE was included in the reaction. This suggests the role of α-helix in promoting protein-protein interactions. Specific SsuD variants were generated in order to investigate the role of these residues in protein-protein interactions and catalysis. Variant containing substitutions at the charged residues showed a six-fold decrease in the activity, while a deletion variant of SsuD lacking the α-helix showed no activity when compared to wild-type SsuD.