Life and Times of Women in Darjeeling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feb 19Th, 2021 D.M. Meeting at 12:30 This

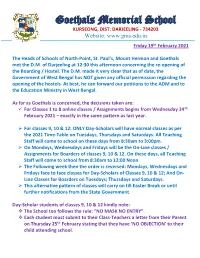

Goethals Memorial School KURSEONG, DIST: DARJEELING - 734203 Website: www.gms.edu.in Friday 19th February 2021 The Heads of Schools of North-Point, St. Paul’s, Mount Hermon and Goethals met the D.M. of Darjeeling at 12:30 this afternoon concerning the re-opening of the Boarding / Hostel. The D.M. made it very clear that as of date, the Government of West Bengal has NOT given any official permission regarding the opening of the hostels. At best, he can forward our petitions to the ADM and to the Education Ministry in West Bengal. As far as Goethals is concerned, the decisions taken are: For Classes 1 to 8 online classes / Assignments begins from Wednesday 24th February 2021 – exactly in the same pattern as last year. For classes 9, 10 & 12: ONLY Day-Scholars will have normal classes as per the 2021 Time-Table on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays. All Teaching Staff will come to school on these days from 8:30am to 3:00pm. On Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays will be the On-Line classes / Assignments for Boarders of classes 9, 10 & 12. On these days, all Teaching Staff will come to school from 8:30am to 12:00 Noon. The Following week then the order is reversed: Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays face to face classes for Day-Scholars of Classes 9, 10 & 12; And On- Line Classes for Boarders on Tuesdays; Thursdays and Saturdays. This alternative pattern of classes will carry on till Easter Break or until further notifications from the State Government. Day-Scholar students of classes 9, 10 & 12 kindly note: The School too follows the rule: “NO MASK NO ENTRY”. -

West Bengal Bikash Bidhan Nagar, Calc Antiual Report 1999-2000

r Department of School Education A Government of West Bengal Bikash Bidhan Nagar, Calc Antiual Report 1999-2000 Department of School Education Government of West Bengal Bikash Bhavan Bidhan Nagar, Calcutta-700 091 \amtuu of B4u«tcioQ«t PiittQiai «a4 A4niMttriti«o. ll^ ii Sri A«ir»kBdo M«rg, ! X a n i i C S i s w a s Minister-in-charge DEPT. OF EDUCATION (PRIMARY, SECONDARY AND MADRASAH) & DEPT. OF REFUGEE RELIEF AND REHABILITATION Government of West Bengal Dated, Calcutta 28.6.2000 FOREWORD It is a matter of satisfaction to me that 4th Annual Report of the Department of School Education, Government of West Bengal is being presented to all concerned who are interested to know the facts and figures of the system and achievements of the Department. The deficiencies which were revealed in the last 3 successive reports have been tried to be overcome in this report. The figures in relation to all sectors of School Education Department have been updated. All sorts of efforts have been taken in preparation of this Annual Report sO that the report may be all embracing in respect of various information of this Department. All the facts and figures in respect of achievement of Primary Education including the District Primary Education Programme have been incorporated in this Report. The position of Secondary School have been clearly adumbrated in this issue. At the same time, a large number of X-class High Schools which have been upgraded to Higher Secondary Schools (XI-XII) have also been mentioned in this Report. -

26 Joraj Memorial 8 and Below Football Tournament

I SSUE 2 A MONG O URSELVES 3 Editorial ith the coming of autumn, North Point now enters Winto a new chapter for this academic year, with its own activities and events to look forward to. With this transition the 'Among Ourselves' Editorial Team present to you the second issue of the 'Among Ourselves' magazine for the year 2019. With this new issue we bring to you new ideas fresh off the boat along with some new additions from the Editorial Team. We are grateful to all the boys who have contributed their articles for this issue and it is our humble request that you continue to do so. Writing, unlike many other art forms, is unique. It single- handedly tests the many abilities and overall calibre of an individual. I believe that all the boys whose articles you shall now read, ranging from the Primary students upto the Senior students, all have managed to push themselves to their individual limits and convey to us their thoughts. I sincerely hope that you, dear reader, will enjoy reading this magazine and feel satisfied with it. The third issue will be the last issue of the 'Among Ourselves' magazine for this year and our plan is to make it the larget issue till date, but we cannot achieve this feat without your support and contributions. So, to all the staff and students of North Point, the water does not flow until the faucet is turned on, so turn on the faucet of your creativity and let it all flow out. The Among Ourselves Editorial Team 2019 Teacher Guide - Mrs. -

Gorkhaland and Madhesi Movements in the Border Area of India and Nepal:A Comparative Study

Gorkhaland and Madhesi Movements in the Border Area of India and Nepal:A Comparative Study A Thesis Submitted To Sikkim University In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Animesh Andrew Lulam Rai Department of Sociology School of Social Sciences October 2017 Gangtok 737102 INDIA ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I have been indebted to very many individuals and institutions to complete this work. First and foremost, with my whole heart I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. Swati Akshay Sachdeva for giving me the liberty, love and lessons to pursue this work. Thank you for your unconditional support and care. Secondly, I would like to thank my former supervisor Dr. Binu Sundas for introducing me to the world of social movements and Gorkhaland. I am equally thankful to Dr. Sandhya Thapa, the Head of the Department of Sociology at Sikkim University, Dr. Indira, Ms. Sona Rai, Mr. Shankar Bagh and Mr. Binod Bhattarai, faculties of Sociology at Sikkim University for all the encouragement, support and care. I would love to express my heartfelt gratitude to Dr. Mona Chettri for the invaluable comments and reading materials. I am ever grateful to the Ministry of Minority Affairs for funding my studies and research at Sikkim University. My heartfelt thanks to Prof. Maharjan, Neeraj da, Suman Da at Hiroshima Univerity. Thanks to Mr. Prashant Jha and Sohan for showing me the crisis of Madhesis. I am also indebted to Prof. Mahendra P. Lama and Prof. Jyoti P. Tamang for all the encouragement and blessings which motivated me to pursue higher studies. -

DEPARTMENT of POSTS, INDIA OFFICE of the CHIEF POSTMASTER GENERAL WEST BENGAL CIRCLE, KOLKATA-700 012. Ph-033-2212 0003 Email- A

DEPARTMENT OF POSTS, INDIA OFFICE OF THE CHIEF POSTMASTER GENERAL WEST BENGAL CIRCLE, KOLKATA-700 012. Ph-033-2212 0003 email- [email protected] To, 1.The PMG, Kolkata Region, Kolkata-7000I2 2. The PMG, North Bengal Region, Siliguri-73400I No.MM&PO/PhiliDeenDayal Sparsh YojanaDtdat Kolkata-700012, 12.03.2018 Subject: Philately Scholarship Scheme - Deen Dayal Sparsh Yojana. In continuation of this office letter of even no. dated 31-01-2018, it is intimated that the list of successful candidates are forwarded herewith for declaring the result. You are requested to arrange to open POSB Alc in the name of the successful candidate in any CBS Post Office and informed this office for taking necessary action as early as possible. In this connection, a copy of the Directorate's letter no.46-59/20 17-Phil dated 06-3-2018 is enclosed herewith for your kind information. Enclo:- As above t.. Asstt. Director of Postal Services (Accounts & Philately) Office of the Chief Postmaster General, West Bengal Circle, Kolkata-700012 ~O:-ADPS(TO)' C.O., Kolkata-700012. He is requested to kindly arrange upload the name of successful candidates for Philately Scholarship in c/w Deen Dayal Sparsh Yojana in Departmental website as early as possible for publicity. A copy of the list of successful candidates is enclosed for necessary action. ~ Asstt. Director of Postal Services (Accounts & Philately) Office of the Chief Postmaster General, West Bengal Circle, Kolkata-7000 12 ", The name of successful candidates for Deen Dayal Philately Scholarship in W.B.Circle. 1.Rajdeb -

2015 Phd Students Research Grant Programme)

Where the English Refused to Tread: India’s Role in Establishing Hockey as an Olympic Summer Sport (Final report submitted to the IOC Olympic Studies Centre in the framework of the 2015 PhD Students Research Grant Programme) By Nikhilesh Bhattacharya PhD Fellow, School of Cultural Texts and Records, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India Abstract: The evolution of field hockey as an Olympic Summer Sport in the inter-war years was marked by two contrasting developments. England, the home of modern hockey, made a solitary appearance in Antwerp in 1920 (where the matches were held in early September) and won gold but thereafter refused to play while the other constituent parts of Great Britain stayed away from Olympic hockey altogether. On the other hand, India, then a colony under British rule, aligned with countries on the Continent and joined the newly founded International hockey federation (FIH) to take part in the 1928 Amsterdam Games and, over the next decade, played a crucial role in keeping hockey within the Olympic fold. My project examines England’s reluctance, and India’s eagerness, in the light of developments that were taking place in the history of hockey, the Olympic Movement and the world at large. This is the first systematic study of the emergence of field hockey as a permanent Olympic Summer Sport (men’s field hockey has been a part of every Olympic Games since 1928) as it covers five archives in two countries, various online databases and a host of secondary sources including official reports, and newspaper and magazine -

CISCE-Book-014-For-Web.Pdf

CATEGORY - I 1st Rank RUBINA SINGH Class XII Hill Top School Jamshedpur Jharkhand EARTH RAIDERS 2075 AD. The moment they landed on the planet, they knew that they had been fooled. They had been promised lush green landscape, turquoise blue oceans and air so sweet, it intoxicated one’s senses. So you can imagine their surprise and dismay when they stepped out of their aircraft and walked right into a concrete jungle. Though the bright lights and the hustle- bustle of the world was a sight to see, the only emotion they felt was disappointment. Earth, they had been told, was God’s most mesmerizing Hill Top School, Jamshedpur creation. The inhabitants of their neighbouring planet, who had been able to get a peek at it, described a Started on August 2nd, 1976 Hill Top School is one of the giant blue ball, a sapphire, shining blindingly, a one premier English medium co educational institutions in the city of Jamshedpur. We aim to facilitate value based holistic of its kind habitat which was inhabited by creatures education that combines the spirit of enquiry with positive social called humans. As soon as they could, they had left attitudes to nurture sensitive human beings. We have indeed for this planet. But to their dismay, in the five hundred made a strong hold in academics, since the year we have had years that it had taken for them to get here, the Earth a state topper in either ICSE or ISC in each of the 5 years from had lost all its former glory. -

Charity Registered in Scotland SC 016341

The induction of the new Headmaster, Mr. Neil Monteiro UK COMMITTEE DR GRAHAM’S HOMES Charity Registered in Scotland SC 016341 ANNUAL REPORT AND SUMMARY ACCOUNTS For the year ended 31 January 2016 MID-YEAR NEWSLETTER MAY 2016 UK Committee Dr. Graham’s Homes, Kalimpong, India Congratulations to all, but especially to Mark Glass, Mathew Francis and Jeremy Jordan whose sponsors are in the UK and to Alister Tucker whose sponsor is in Australia. 2 Charity recognised in Scotland SC 016341 UK Committee Dr. Graham’s Homes, Kalimpong, India DR GRAHAM’S HOMES, KALIMPONG, INDIA 1900 - 2016 OVER A CENTURY OF CARING FOR CHILDREN Founder - The Very Reverend John Anderson Graham DD, LL.B, CIE Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, 1931 The Very Reverend Dr. John A Graham and Mrs. Katherine Graham 3 Charity recognised in Scotland SC 016341 UK Committee Dr. Graham’s Homes, Kalimpong, India UK Committee Dr. Graham’s Homes, Kalimpong, India Also known as: Dr. Graham’s Homes, Kalimpong, India: UK Committee Charity Registered in Scotland SC 016341 Registered Address: 44 Aytoun Road, Pollokshields, Glasgow G41 5HN www.drgrahamshomes.co.uk Associated Organisation: Dr. Graham’s Homes (Greetings Cards) Ltd Referred to as “DGH Greetings Cards Ltd” Annual Reports and Summary Accounts For the Year Ended 31st January 2016 CONTENTS PAGE [Photo] Very Reverend Dr. John Graham & Mrs. Katherine Graham 3 The Trustees of the Charity 5 Chairman’s Report, Mr. James MacHardy 6 Report of the Sponsorship Secretary, Mr. James Simpson 7 Report of the Committee Secretary, Anne Hoggan 10 Notice of the AGM 11 Report of the Treasurer, Mr. -

Uk Committee Dr Graham's Homes

WITH A SPECIAL FOCUS ON LUCIA KING UK COMMITTEE DR GRAHAM’S HOMES Charity Registered in Scotland SC 016341 ANNUAL REPORT AND SUMMARY ACCOUNTS For the year ended 31 January 2015 MID-YEAR NEWSLETTER MAY 2015 UK Committee Dr. Graham’s Homes, Kalimpong, India A montage of the children having lots of fun 2 Charity recognised in Scotland SC 016341 UK Committee Dr. Graham’s Homes, Kalimpong, India DR GRAHAM’S HOMES, KALIMPONG, INDIA 1900 - 2015 OVER A CENTURY OF CARING FOR CHILDREN Founder - The Very Reverend J.A Graham DD, LL.B, CIE Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, 1931 The Very Reverend Dr. John A Graham and Mrs. Katherine Graham 3 Charity recognised in Scotland SC 016341 UK Committee Dr. Graham’s Homes, Kalimpong, India UK Committee Dr. Graham’s Homes Also known as: Dr. Graham’s Homes, Kalimpong, India: UK Committee Charity Registered in Scotland SC 016341 Principal Office: 37 Campbell Drive, Bearsden, Glasgow, G61 4NF www.drgrahamshomes.co.uk Associated Organisation: Dr. Graham’s Homes (Greetings Cards) Ltd Referred to as “DGH Greetings Cards Ltd” Annual Reports and Summary Accounts For the Year Ended 31st January 2015 CONTENTS PAGE [Photo] Very Reverend Dr. John Graham & Mrs. Katherine Graham 3 The Trustees of the Charity 5 Chairman’s Report, Mr. James Simpson 6 Report of the Sponsorship Secretary, Mr. James Simpson 9 Report of the Treasurer, Mr. Jim Gibson 11 [Extract of the] Annual Accounts 2015, Mr. Jim Gibson 15 Investment Report, Mr. Jim Gibson 17 Report of the Committee Secretary, Anne Hoggan 19 Notice of the AGM 19 School Facts and Figures 20 School Calendar 2015 21 & 22 [Photo] Col. -

Annual Report on the Work of the Ali S. K. Memorial Society for the Children for the Year 2007-08

Annual Report on the work of the Ali S. K. Memorial Society for the Children for the year 2007-08 1. Introduction The past financial year was a jubilee of sorts, as it was now already the tenth year since the formation of the Ali S. K. Memorial Society for the Children (ASKMSC) and while the first half of the year was mainly marked by attempts to overcome the problems inherited from the previous year the second half allowed us to focus on our main objectives again, which are giving food, shelter and education to destitute children. This was also reflected in the beginning of new admissions towards the end of that year. 2. Activities: (i) General – The financial year 2007-2008 was already the tenth year since the ASKMSC was founded and registered in 1998 and after one decade of service for the welfare of street children it can be considered a well recognized organisation in the field of child welfare now. Initial struggles to get established are over now and even problems that occurred in the previous year due to the removal of some criminal elements within our society could eventually be overcome this year. The Directorate of Social Welfare finally renewed our licence to run our home for street children and things came back to normal again in the second half of the year. We were therefore able to start with new admissions again and in February 2008 an eight-year-old boy named Samir Mondal was admitted from Loreto’s Rainbow Shelter. This means the total number of children in our project reached 41 now. -

Goethals Memorial School

+91-9800068004 Goethals Memorial School https://www.indiamart.com/goethals-memorial-school/ Goethals Memorial School is a boarding school run by the Congregation of Christian Brothers in India. It is set in a forest 5 km (3 miles) from Kurseong between Siliguri and Darjeeling at an altitude of 1674 meters (5500 feet) above sea level. The ... About Us Goethals Memorial School is a boarding school run by the Congregation of Christian Brothers in India. It is set in a forest 5 km (3 miles) from Kurseong between Siliguri and Darjeeling at an altitude of 1674 meters (5500 feet) above sea level. The school was founded in 1907, and is named after Jesuit Archbishop of Calcutta (now Kolkata), Paul Goethals. The land for the school was donated by the Maharaja of Bardhaman. Goethals attracts students from West Bengal, Bihar, north-eastern Indian states, Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh. It follows the Indian Certificate of Secondary Education curriculum, and has classes from standard KG (Kindergarten) to standard 12. On the death of Paul Goethals, Archbishop of Calcutta, in July 1901 the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Calcutta commemorated his memory by the establishment of an educational institution for boys in Kurseong. In February 1907 classes started in the building erected by the first Principal, Br. M.S.O. Brien (1907– 1914). The number of boys in residence was 110. The official opening took place on 30 April 1907. The first prospectus had in view the affiliation of the School to the Shibpur Engineering College, Calcutta. However, the Sub Overseer Course did not fit with the needs of the pupils and was dropped in favour of the Cambridge Locals. -

Kalimpong OVER a CENTURY of CARING for CHILDREN

Dr. Graham’s Homes – Kalimpong OVER A CENTURY OF CARING FOR CHILDREN SCHOOL CALENDAR – 2021-22 JANUARY Friday – 1 :New Year’s Day. Monday-4 :Online classes resume for classes 10’s,11’s &12’s Wednesday-20 :New Academic session for classes Nursery to 10(With Online classes) commence Friday-22 :Last day for online classes for 10,11 &12 Saturday-23 : Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’ Birth Anniversary. Tuesday-26 : Republic Day. FEBRUARY Friday–5 : Pre-Board Exam for 10 &12 and Final Assessment for 11 commences. Wednesday– 17 : Last Day of Examination/Assessment for 10,11 &12 . MARCH Monday – 1 : New Academic Session for class 12 commence. Friday-5 : 1st PET’s meeting at DGH Thursday –11 : Inter Cottage Debate Commences. Wednesday-17 :1st Unit Test Classes 3-10. Thursday-18 :1 st Unit Test Friday-19 :1 st Unit Test Monday-22 :1 st Unit Test Tuesday-23 :1 st Unit Test Thursday -25 : Junior Basketball for Girls & Boys of Class – 7 & below at St. Augustine’s School, Friday-26 Kalimpong. Saturday-27 : Inter-School Chess (Boys &Girls) at Victoria Boys’ School, Kurseong. Monday-29 :Holi School Holiday Monday- 29 to 31 : Cricket U-14 Boys at St. Paul’s School, Darjeeling. APRIL Thursday–1 :Maundy Thursday. School Holiday. Friday – 2 : Good Friday. School Holiday. Saturday–3 : Holy Saturday. School Holiday. Sunday – 4 : Easter Sunday. Monday – 5 : Easter Monday. School Holiday. Saturday – 10 : Basketball for Boys( Class – 8 & below )at St. Joseph’s School, NP, Darjeeling. (Fr. Kinley Tournament). Wednesday – 14 :Dr. Ambedkar’s Jayanti. School Holiday.