2015 Phd Students Research Grant Programme)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 1982 • Wire Service Notre Dame, in 46556

SCHOLASTIC Vol. 123, No.5, January 1982 • Wire Service Notre Dame, IN 46556 • Corsages FEATURES • Gift Items 3 Notre Dame Football: The Rainy Season A recapy of Faust's first . .. Mike Dorociak • Arrangements 6 Volleyball: A Decade of Experience • Plants Saint Mary's captain reflects on her athletic career . .. Theresa Walters • Silk Flowers 8 An Old Game That Hasn't Changed • Free SMC delivery - Notre Dame Woman take to field hockey . .. Kathy Ray 50c ND delivery - 10 Jump Ball, Center Court Notre Dame Women's Basketball: Hail Mary! • Centerpieces Let's Go ... Jenny Klauke 11 The Rational Athlete • Accessories Fencing~the assassin's pax de Deux ... Scott Thomas ~ 12 Fellowship of Christian Athletes: Faith on the Playing Field ..---=r:~4\.---r• r-:::~::-l Seeking to understand Christ and one another. Dale Fronk Discounts on .,.;, -I E.,·"".... D A-r AV ~~oodH,:.~eePi:.w·*""·~ page 3 1 FlO'~~ l'tltrIJTO ••lfU"Olfl)\.\~ 14 Notre Dame Women's Tennis "THlSSUlInUESTOnowu Call (219) FlO'lru$IJIOPLllflSOIIlr. Serving up a successful season . .. Tina Stephan GUARANTEED FRESH I SERVICE WORLDWIDE I 18 Notre Dame Volleyball Grows Up Spiking with a punch . .. Jan Yurgealitis I 20 "I Need Two!" The competition outside the stadium . .. Philip Allen 22 1981 Football Statistics LAMP SHADES - LAMP REPAIR - LAMP PARTS GLASS PARTS - LAMPS - LIGHTING FIXTURES REGULARS· ACE 2 Up Front Ed Kelly HARDWARE Village 16 Gallery 24 FictionlThe Exchange Program Sheila Beatty LampShoppe 25 Fiction/Getting On Beth Healy ACE IS THE PLACE 28 Poetry Mary Francis DeCelles, Kathleen Johannsen WITH THE HELPFUL HARDWARE MAN 31 Culture Update NORTH VILLAGE MALL ,. -

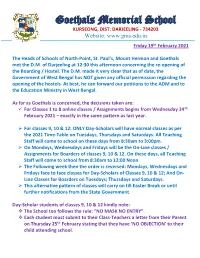

Feb 19Th, 2021 D.M. Meeting at 12:30 This

Goethals Memorial School KURSEONG, DIST: DARJEELING - 734203 Website: www.gms.edu.in Friday 19th February 2021 The Heads of Schools of North-Point, St. Paul’s, Mount Hermon and Goethals met the D.M. of Darjeeling at 12:30 this afternoon concerning the re-opening of the Boarding / Hostel. The D.M. made it very clear that as of date, the Government of West Bengal has NOT given any official permission regarding the opening of the hostels. At best, he can forward our petitions to the ADM and to the Education Ministry in West Bengal. As far as Goethals is concerned, the decisions taken are: For Classes 1 to 8 online classes / Assignments begins from Wednesday 24th February 2021 – exactly in the same pattern as last year. For classes 9, 10 & 12: ONLY Day-Scholars will have normal classes as per the 2021 Time-Table on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays. All Teaching Staff will come to school on these days from 8:30am to 3:00pm. On Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays will be the On-Line classes / Assignments for Boarders of classes 9, 10 & 12. On these days, all Teaching Staff will come to school from 8:30am to 12:00 Noon. The Following week then the order is reversed: Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays face to face classes for Day-Scholars of Classes 9, 10 & 12; And On- Line Classes for Boarders on Tuesdays; Thursdays and Saturdays. This alternative pattern of classes will carry on till Easter Break or until further notifications from the State Government. Day-Scholar students of classes 9, 10 & 12 kindly note: The School too follows the rule: “NO MASK NO ENTRY”. -

N O T E ---A Special Lok Adalat Is Going to Be Held on 07.05.2016 (SATURDAY) in the Premises of This Hon R

file:///C:/Users/Administrator/Desktop/New folder (2)/2016_05_06_o_m.htm N O T E ------------------------ A Special Lok Adalat is going to be held on 07.05.2016 (SATURDAY) in the premises of this Hon’ble High Court headed by Hon'ble Mr. Justice K. Kannan in court room no. 20 at 11:00 a.m. All the cases which were earlier listed for 02.04.2016(Saturday) and adjourned for 30.04.2016(Saturday) will now be taken up on 07.05.2016(Saturday). -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NOTICE ------------------------- Learned members of the Bar are hereby informed that the Hon'ble Acting Chief Justice has been pleased to order that the Criminal Revisions (10 each, from the enclosed list) shall be listed on every Wednesday and Friday from 30.03.2016 onwards, before the Hon'ble Single benches sitting in Criminal Roster except Hon'ble judges dealing exclusively with bail matters, Crime Against Women and Prevention of corruption Act cases and would be taken up on priority basis. sd/- Joint Registrar(Judicial-II) Sr.No. Type No. Year 1 CRR 27 2004 2 CRR 1084 2004 3 CRR 1169 2004 4 CRR 1651 2004 5 CRR 1464 2004 6 CRR 2002 2004 7 CRR 2637 2004 8 CRR 1911 2004 9 CRR 258 2004 10 CRR 1789 2005 11 CRR 809 2005 12 CRR 316,296 2005 13 CRR 1899 2005 14 CRR 2413 2005 15 CRR 878 2005 16 CRR 1218 2005 17 CRR 659 2005 18 CRR 1476 2005 19 CRR 1536 2005 20 CRR 879 2005 21 CRR 23 2005 22 CRR 1194 2006 23 CRR 1837 2006 24 CRR 1487 2006 25 CRR 1625 2006 26 CRR 1664 2006 27 CRR 1873 2006 -

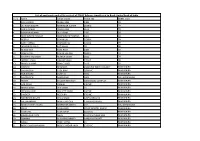

List of Applicants Under Clss Vertical of PMAY Scheme Transferred to Bank

List of applicants under Clss vertical of PMAY Scheme transferred to Bank-United bank of India Sr.no Name Father_Name House_No Street_Slum 1 SHIV KUMAR MUNSI RAM 1381 39 2 JATINDER KUMAR MOHINDER KUMAR 2538/G 39 3 SUNIL KUMAR PHULA RAM 2612 39 4 ASHWANI KUMAR DULO RAM 2585 39 5 MOHAMMAD YOUSUF MOHAMMAD YOUNUS B-14 39 6 NEERAJ SOHAN LAL 3138/A 39 7 AARTI VERMA BRAHAM PAL 1350/A 39 8 JASWINDER KAUR AJIT SINGH 20 39 9 MINDA DEVI KAKA RAM 2483 39 10 KESHAV GILL SOHAN LAL GILL 2602/A 39 11 KRISHAN PAL SINGH MUNNA SINGH 2582 39 12 JARNAIL SINGH UJAGAR SINGH 1709/1 39 13 MANOJ KUMAR GIAN CHAND 3119 39 14 ROSHAN MASROOR 2344 NEW INDIRA COLONY MANIMAJRA 15 SAVITRI DEVI TUDE RAM 2036 NIC MANIMAJRA 16 ROBIN GARG GORE LAL 1890 MANIMAJRA 17 SAVITRI DEVI RAM NIHAR 1809 NIC, MANIMAJRA 18 MEERA BALGOVIND SINGH 2800 MOULI COMPLEX MANIMAJRA 19 HAR PYARI LAKHAN 240 NIC MANIMAJRA 20 MANJIT KAUR DEV SINGH 73 MANIMAJRA 21 KRISHNA KAUR MALKEET SINGH 260 NIC MANIMAJRA 22 SANDEEP MEGH RAJ 670 NIC MANIMAJRA 23 NOORESHA BEGAM INSUL NADAF 1237 MORIGATE MANIMAJRA 24 FAEEM AHMAD MOND SADIQUE 1786/4 MORIGATE MANIMAJRA 25 MOND YUSUF JULAHA MOHBOOB ANMED 452 NIC, MANIMAJRA 26 VIKAS RAJ KUMAR 325/D SHASTRI NAGAR MANIMAJRA 27 RAM VATI RAM AVTAR 2151 NIC MANIMAJRA 28 ZAHIDA KHATOON NAFIS 1119/2 GOVINDPURA MANIMAJRA 29 SHAHNAJ MUKHIYAR ANMED 1048/1 MORIGATE MANIMAJRA 30 ANJALI PRABHUDYAL 46 MANIMAJRA 31 MOND SHADMAN KHAN MOND SARDAR KHAN 1242 NIC MANIMAJRA 32 PANKAJ NEGI PARBAL SINGH 1299/1 NAGLA BASTI MANIMAJRA 33 RAJ KUMARI MUNSHI RAM 2238/34 PIPLIWALA TOWN, MANIMAJRA -

NOVEMBER SESSION- 2017-18 CLASS- KINDERGARTEN General

“Creating Global heads with hearts” PLANNER OF THE MONTH- NOVEMBER SESSION- 2017-18 CLASS- KINDERGARTEN General Awareness - Popular Sports Personalities:- Sport :Sport is an activity involving physical exertion and skill in which an individual or team competes against another or others for entertainment. Some of the famous sport personalities are: Milkha Singh : Milkha Singh is a former Indian track and field sprinter who was introduced tothe sport while serving in the Indian Army.He was the first Indian male athlete to win an individual athletics gold medal at a Commonwealth Games. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ps626ppdLzk Saina Nehwal :Saina Nehwal is a badminton player from India who is among the world’s top players in women’s badminton. She got the Arjuna Award in 2009 and won the gold medal at the Commonwealth Games in 2010. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VgfzlHwKs5g Sachin Tendulkar:Sachin Ramesh Tendulkar is a former Indian cricketer and a former captain, widely regarded as one of the greatest batsmen of all time. He is the onlyplayer to score 30,000 runs in international cricket. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rwkS3euRIas Tom Brady :Thomas Edward Patrick Brady Jr. is an American football quarterback for the New England Patriots of the National Football League. He is one of only two players to win five Super Bowls and the only player to win them all playing for one.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ECVsL0rSNDs Dhyan Chand :Dhyan Chand was the greatest field hockey players of all time. He is known for his extraordinary goal-scoring feats, in addition to earning three Olympic gold medals (1928, 1932, and 1936) in field hockey. -

Telegram Groups

www.gradeup.co Current Affairs of the Week 11-17 April 2021 Ghaziabad issues India’s first municipal green bonds • Ghaziabad Nagar Nigam (GNN) has announced successfully raising and listing India’s first Green Municipal bond issue. • GNN raised ₹150 crore at a cost of 8.1%. • This fund will be used to clean dirty water by setting up a tertiary water treatment plant and supply piped water through water-meters to places like Sahibabad • Ghaziabad is debt-free and has maintained a revenue surplus position in the last few years, according to India Ratings, which rated the paper. Government launches Mass Vaccination Programme ‘Teeka Utsav’ • Govt has launched mass vaccination programme titled as Teeka Utsav (Vaccine Festival) in fight against COVID-19 • It will be held from April 11 (birth anniversary of Jyotiba Phule) to 14 (birth anniversary of Jyotiba Phule), 2021 • It is a nation-wide vaccination drive and will be observed as vaccination festival to inoculate maximum number of eligible people against the coronavirus • All eligible persons can book an appointment with CoWIN portal and Aarogya Setu App Telegram Groups NDA & Other Exams: https://t.me/joinchat/TX7hKUXmUvKsOL5IFHsbRA CDS & Defence Exams: https://t.me/joinchat/TX7hKVbSbpp5PDJuRccltw Air Force X & Y: https://t.me/GradeupAirforce India-Netherlands Virtual Summit held • PM Modi and Prime Minister of Netherlands Mark Rutte, held virtual summit • During this, two leaders reviewed the existing bilateral engagements and also exchanged views on further expanding and diversifying the -

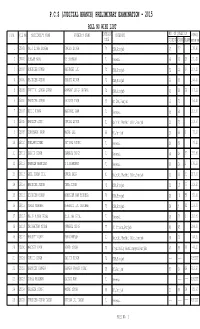

P.C.S (Judicial Branch) Preliminary Examination - 2015 Roll No Wise List S.No

P.C.S (JUDICIAL BRANCH) PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION - 2015 ROLL NO WISE LIST S.NO. ROLL NO CANDIDATE'S NAME FATHER'S NAME CATEGORY CATEGORY NO. OF QUESTION MARKS CODE CORRECT WRONG BLANK (OUT OF 500) 1 25001 NAIB SINGH SANGHA GURDEV SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab 48 77 130.40 2 25002 NEELAM RANI OM PARKASH 71 General 45 61 19 131.20 3 25003 AMNINDER KUMAR KASHMIRI LAL 72 ESM,Punjab 32 26 67 107.20 4 25004 RAJINDER SINGH SANGAT SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab 56 69 168.80 5 25005 PREETPAL SINGH GREWAL HARWANT SINGH GREWAL 72 ESM,Punjab 41 58 26 117.60 6 25006 NARENDER SINGH DAULATS INGH 86 BC ESM,Punjab 53 72 154.40 7 25007 RISHI KUMAR MANPHOOL RAM 71 General 65 60 212.00 8 25008 HARDEEP SINGH GURDAS SINGH 81 Balmiki/Mazhbi Sikh,Punjab 52 73 149.60 9 25009 GURCHARAN KAUR MADAN LAL 85 BC,Punjab 36 88 1 73.60 10 25010 NEELAMUSONDHI SAT PAL SONDHI 71 General 29 96 39.20 11 25011 DALVIR SINGH KARNAIL SINGH 71 General 44 24 57 156.80 12 25012 KARMESH BHARDWAJ S L BHARDWAJ 71 General 99 24 2 376.80 13 25013 ANIL KUMAR GILL DURGA DASS 81 Balmiki/Mazhbi Sikh,Punjab 61 33 31 217.60 14 25014 MANINDER SINGH TARA SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab 31 19 75 108.80 15 25015 DEVINDER KUMAR MOHINDER RAM BHUMBLA 72 ESM,Punjab 25 10 90 92.00 16 25016 VIKAS GIRDHAR KHARAITI LAL GIRDHAR 72 ESM,Punjab 34 9 82 128.80 17 25017 RAJIV KUMAR GOYAL BHIM RAJ GOYAL 71 General 45 79 1 116.80 18 25018 NACHHATTAR SINGH GURMAIL SINGH 77 SC Others,Punjab 80 45 284.00 19 25019 HARJEET KUMAR RAM PARKASH 81 Balmiki/Mazhbi Sikh,Punjab 55 70 164.00 20 25020 MANDEEP KAUR AJMER SINGH 76 Physically Handicapped,Punjab 47 59 19 140.80 21 25021 GURDIP SINGH JAGJIT SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab --- --- --- ABSENT 22 25022 HARPREET KANWAR KANWAR JAGBIR SINGH 85 BC,Punjab 83 24 18 312.80 23 25023 GOPAL KRISHAN DAULAT RAM 71 General --- --- --- ABSENT 24 25024 JAGSEER SINGH MODAN SINGH 85 BC,Punjab 33 58 34 85.60 25 25025 SURENDER SINGH TAXAK ROSHAN LAL TAXAK 71 General --- --- --- ABSENT PAGE NO. -

Centrespread Centrespread 13 JANUARY 13-19, 2019 JANUARY 13-19, 2019

12 centrespread centrespread 13 JANUARY 13-19, 2019 JANUARY 13-19, 2019 Hockey Cricket 1975: Golden Age Ends The 1975 World Cup victory has remained the last tri- 1983: Triumph of the Underdog umph of Indian hockey, which had dominated the event India has won the World Cup thrice: the ODI cup at the Olympics for decades. India, captained by Ajit Pal in 1983 and 2011 and the T20 World Cup in 2007. Singh, defeated Pakistan by a margin of 2-1. The winning However, the 1983 victory of the Prudential Cup, goal was scored by Ashok Kumar, the son of legendary as the World Cup was known then, in England was hockey great Dhyan Chand. However, the goal wasn’t special as no one gave India a chance of winning the without its own share of drama as Pakistan players tournament. India was not seen as a winning team claimed the ball had not crossed the goal line. even when it reached the semi-fi nal. But it defeated the hosts and went on to take on then cricketing giants A victory in sports becomes sweeter West Indies. The fi nal was an upset of even greater proportions. Indian bowlers bundled out West Indies when it brings back memories of earlier batsmen for 140, after setting a paltry target of 183. triumphs. Virat Kohli, for example, 2007: Epoch Win said India winning the Test series India’s victory over Pakistan at the fi nal of the inaugural against Australia on January 7 was T20 World Cup in 2007 left a lasting impact on the game. -

International Leaders

International Leaders Country Name Info Jigme Khesar Namgyel Bhutan King of Bhutan. Chief guest for 26th Jan. 2013. Wangchuck First woman President of Brazil. She replaced Lula Desilva. Brazil Dilma Rousseff (Lula got Indira Gandhi peace prize.) Replaced Hu Jintao, China. He is expected to become China Xi Jingping President, in March 2013. China Li Kequiang New PM of China. Replaced Wen Jiabao. China Bo Xilai corrupt leader in Chinese politbureu. Expelled Cuba Raul Castro President of Cuba. Replaced Fidel Castro Egypt Mohd. Morsy President of Egypt. Eu Herman Van Rompuy PM of Belgium. President of European Council President of France. He defeated Sarkozi. Belongs to Socialist France Francois Hollande party PM Greece. Name is important only because Greece Atonis Samras Greece=#EPICFAIL economy. Iran Aytollah Khamenei Supreme leader of Iran Iran Ahmedijad President of Iran. President Shimon Peres. Israel PM Benjamin Their parliament =Knesset. Netanyahu. Japan Shinzo Abe PM japan. Defeated Yoshiko Noda. Their parliament =Diet. Liberia Ellen Sirleaf President of Liberia, got Indira Gandhi peace price. (2012) Maldives Nasheed N Waheed after coup, Nasheed was replaced by Waheed -Coup Mali-coup Diarra N Traore After coup, Diarra was replaced by Traore President of Mauratius. He was chief guest @Pravasi bharatiya Mauritius Rajkeshwur Purryag Divas 2013 Mexico Enrique Nieto Mexico new President Myanmar Thein Sein Myanmar president Nobel peace 91. Opposition leader in Myanmar. Party Myanmar Aung San Suu Ki National league for democracy. Visited India in Nov 12 N.Korea Kim Jong-Un North Korea President. After his father King Jong-il Died Pak Raja Parvez PM of Pakistan, SC ordered his arrested. -

West Bengal Bikash Bidhan Nagar, Calc Antiual Report 1999-2000

r Department of School Education A Government of West Bengal Bikash Bidhan Nagar, Calc Antiual Report 1999-2000 Department of School Education Government of West Bengal Bikash Bhavan Bidhan Nagar, Calcutta-700 091 \amtuu of B4u«tcioQ«t PiittQiai «a4 A4niMttriti«o. ll^ ii Sri A«ir»kBdo M«rg, ! X a n i i C S i s w a s Minister-in-charge DEPT. OF EDUCATION (PRIMARY, SECONDARY AND MADRASAH) & DEPT. OF REFUGEE RELIEF AND REHABILITATION Government of West Bengal Dated, Calcutta 28.6.2000 FOREWORD It is a matter of satisfaction to me that 4th Annual Report of the Department of School Education, Government of West Bengal is being presented to all concerned who are interested to know the facts and figures of the system and achievements of the Department. The deficiencies which were revealed in the last 3 successive reports have been tried to be overcome in this report. The figures in relation to all sectors of School Education Department have been updated. All sorts of efforts have been taken in preparation of this Annual Report sO that the report may be all embracing in respect of various information of this Department. All the facts and figures in respect of achievement of Primary Education including the District Primary Education Programme have been incorporated in this Report. The position of Secondary School have been clearly adumbrated in this issue. At the same time, a large number of X-class High Schools which have been upgraded to Higher Secondary Schools (XI-XII) have also been mentioned in this Report. -

Field Hockey

HOME OF THE NINE-TIME NCAA NATIONAL CHAMPIONS 1982 TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION .................... 2-3 1983 Media Instructions ......................................................... 2 Why Monarchs? ............................................................. 2 1984 Quick Facts ................................................................... 2 Media List ................................................................... 3 1988 Directions to Foreman Field ........................................... 3 THE GAME OF FIELD HOCKEY ........ 4-5 1990 Game Basics 4 The Field ................................................ 4 Rules of the Game .......................................................... 4-5 1991 History of the Game ....................................................... 5 Coaching Staff ..................................... 6-8 1992 Head Coach Beth Anders ............................................... 6-7 1998 Beth Anders' Year-by-Year Record ................................. 7 Assistant Coaches .......................................................... 8 2000 THE 2005 LADY MONARCHS .......... 9-15 2005 Outlook .................................................................. 9 2005 Rosters ................................................................... 10 Player Information .......................................................... 11-15 2004 IN REVIEW ................................ 16-17 1 2004 Old Dominion Statistics ......................................... 16 2004 Wrap-Up ............................................................... -

The Legality of Male Athletes in Interscholastic Field Hockey

1 WILLAMETTE SPORTS LAW JOURNAL SPRING 2013 Playing Between the Lines: The Legality of Male Athletes in Interscholastic Field Hockey Jared A. Fiore* Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 1 I. Background ............................................................................................................................................... 2 II. Common Concerns: Fairness & Safety ................................................................................................... 4 A. Fairness ............................................................................................................................................... 4 B. Safety ................................................................................................................................................... 6 III. Legal Avenues for Challenge: Title IX, Equal Protection, and Equal Rights ....................................... 6 A. Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 ................................................................................. 7 (i) Athletic Opportunities Test ............................................................................................................................................... 9 (ii) Contact Sports Exception ............................................................................................................................................... 10 B. Equal Protection Clause