RASTER of MUSIC By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

Manfred Honeck, Conductor Vilde Frang, Violin Matthias Goerne, Baritone Eric Cutler, Tenor

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2018-2019 Mellon Grand Classics Season May 10 and 12, 2019 MANFRED HONECK, CONDUCTOR VILDE FRANG, VIOLIN MATTHIAS GOERNE, BARITONE ERIC CUTLER, TENOR LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Concerto in D major for Violin and Orchestra, Opus 61 I. Allegro ma non troppo II. Larghetto — III. Rondo: Allegro Ms. Frang Intermission GUSTAV MAHLER Das Lied von der Erde for Baritone* and Tenor† Soloists and Orchestra I. Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde (“The Drinking Song of the Earth’s Misery”)† II. Der Einsame im Herbst (“The Lonely One in Autumn”)* III. Von der Jugend (“of Youth”)† IV. Von der Schönheit (“of Beauty”)* V. Der Trunkene im Frühling (“The Drunkard in Spring”)† VI. Der Abschied (“The Parting”)* Mr. Goerne Mr. Cutler May 10-12, 2019, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Concerto in D major for Violin and Orchestra, Opus 61 (1806) Ludwig van Beethoven was born in Bonn on December 16, 1770, and died in Vienna on March 26, 1827. He composed his Violin Concerto in 1806, and it was premiered at the Theater-an-der-Wien in Vienna with Beethoven conducting and soloist Franz Clement on December 23, 1806. The Pittsburgh Symphony first performed the concerto at Carnegie Music Hall with conductor Victor Herbert and violinist Luigi von Kunits in November 1898, and most recently performed it with music director Manfred Honeck and violinist Christian Tetzlaff in June 2015. The score calls for flute, pairs of oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns, and trumpets, timpani and strings. Performance time: approximately 45 minutes. In 1794, two years after he moved to Vienna from Bonn, Beethoven attended a concert by an Austrian violin prodigy named Franz Clement. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Abulfeda crater chain (Moon), 97 Aphrodite Terra (Venus), 142, 143, 144, 145, 146 Acheron Fossae (Mars), 165 Apohele asteroids, 353–354 Achilles asteroids, 351 Apollinaris Patera (Mars), 168 achondrite meteorites, 360 Apollo asteroids, 346, 353, 354, 361, 371 Acidalia Planitia (Mars), 164 Apollo program, 86, 96, 97, 101, 102, 108–109, 110, 361 Adams, John Couch, 298 Apollo 8, 96 Adonis, 371 Apollo 11, 94, 110 Adrastea, 238, 241 Apollo 12, 96, 110 Aegaeon, 263 Apollo 14, 93, 110 Africa, 63, 73, 143 Apollo 15, 100, 103, 104, 110 Akatsuki spacecraft (see Venus Climate Orbiter) Apollo 16, 59, 96, 102, 103, 110 Akna Montes (Venus), 142 Apollo 17, 95, 99, 100, 102, 103, 110 Alabama, 62 Apollodorus crater (Mercury), 127 Alba Patera (Mars), 167 Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), 110 Aldrin, Edwin (Buzz), 94 Apophis, 354, 355 Alexandria, 69 Appalachian mountains (Earth), 74, 270 Alfvén, Hannes, 35 Aqua, 56 Alfvén waves, 35–36, 43, 49 Arabia Terra (Mars), 177, 191, 200 Algeria, 358 arachnoids (see Venus) ALH 84001, 201, 204–205 Archimedes crater (Moon), 93, 106 Allan Hills, 109, 201 Arctic, 62, 67, 84, 186, 229 Allende meteorite, 359, 360 Arden Corona (Miranda), 291 Allen Telescope Array, 409 Arecibo Observatory, 114, 144, 341, 379, 380, 408, 409 Alpha Regio (Venus), 144, 148, 149 Ares Vallis (Mars), 179, 180, 199 Alphonsus crater (Moon), 99, 102 Argentina, 408 Alps (Moon), 93 Argyre Basin (Mars), 161, 162, 163, 166, 186 Amalthea, 236–237, 238, 239, 241 Ariadaeus Rille (Moon), 100, 102 Amazonis Planitia (Mars), 161 COPYRIGHTED -

John Alden Carpenter Collection

John Alden Carpenter Collection Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2005 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Catalog Record: http://lccn.loc.gov/2010563508 Finding Aid encoded by Library of Congress Music Division, 2005 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu003001 Latest revision: 2012 February Collection Summary Title: John Alden Carpenter Collection Span Dates: 1891-1961 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1900-1949) Call No.: ML31.C34 Creator: Carpenter, John Alden, 1876-1951 Extent: around 1,700 items ; 12 boxes ; 5 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: John Alden Carpenter was an American composer. The collection contains music materials, primarily holograph manuscripts of Carpenter's songs, chamber and orchestral pieces, and dramatic works; correspondence; writings; photographs and artwork; biographical materials; certificates and honors; programs; clippings; and scrapbooks. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Carpenter, John Alden, 1876-1951--Archives. Carpenter, John Alden, 1876-1951--Correspondence. Carpenter, John Alden, 1876-1951--Manuscripts. Carpenter, John Alden, 1876-1951--Photographs. Carpenter, John Alden, 1876-1951. Carpenter, John Alden, 1876-1951. Carpenter, John Alden, 1876-1951. Selections. Chadwick, G. W. (George Whitefield), 1854-1931--Correspondence. Damrosch, Walter, 1862-1950--Correspondence. Grainger, Percy, 1882-1961--Correspondence. Stock, Frederick, 1872-1942--Correspondence. -

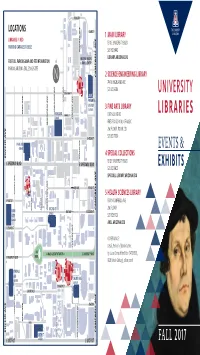

2017 Fall Event Brochure

RING RD LOCATIONS ELM ST 1 MAIN LIBRARY LIBRARIES IN RED 1510 E UNIVERSITY BLVD PARKING GARAGES IN BLUE WARREN AVE WARREN 520.621.6442 ARIZONA HEALTH LIBRARY.ARIZONA.EDU FOR FULL PARKING MAP AND FEE INFORMATION SCIENCES CENTER PARKING.ARIZONA.EDU, 520.626.7275 CAMPBELL AVE CAMPBELL 2 SCIENCE-ENGINEERING LIBRARY 744 N HIGHLAND AVE 520.621.6384 E DRACHMAN ST UAMC VINE AVE PATIENT & VISITOR GARAGE 3 FINE ARTS LIBRARY HIGHLAND AVE PARK AVE PARK HIGHLAND E MABEL ST 1017 N OLIVE RD GARAGE AVE CHERRY FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC MOUNTAIN AVE MOUNTAIN 2nd FLOOR, ROOM 233 E HELEN ST 520.621.7009 PARK AVE GARAGE 4 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS EUCLID AVE WARREN AVE WARREN 1510 E UNIVERSITY BLVD E SPEEDWAY BLVD E SPEEDWAY BLVD 520.621.6423 SPECCOLL.LIBRARY.ARIZONA.EDU ONE WAY E FIRST ST MUSIC TYNDALL AVE TYNDALL BLDG 5 HEALTH SCIENCES LIBRARY E FIRST ST 1501 N CAMPBELL AVE MOUNTAIN AVE MOUNTAIN CAMPBELL AVE CAMPBELL PALM DR PALM OLIVE RD SECOND ST 2nd FLOOR MAIN ONE WAY E SECOND ST GATE GARAGE 520.626.6125 GARAGE AHSL.ARIZONA.EDU E SECOND ST COVER IMAGE: CHERRY AVE CHERRY Detail, Portrait of Martin Luther, OLD MALL CLOSED TO TRAFFIC E UNIVERSITY BLVD by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553), MAIN E UNIVERSITY BLVD 1528 (Veste Coburg), oil on panel TYNDALL AVE GARAGE CHERRY AVE GARAGE E FOURTH ST E FOURTH ST CHERRY AVE CHERRY ENKE DR TYNDALL AVE TYNDALL PARK AVE PARK LOWELL CAMPBELL AVE CAMPBELL EUCLID AVE NAT’L CHAMPIONS DR CHAMPIONS NAT’L SIXTH ST HIGHLAND AVE E SIXTH ST GARAGE E SIXTH ST FALL 2017 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS SPECIAL EVENTS speccoll.library.arizona.edu Library Cats Tech Breakfast Contact: Kathy McCarthy | 520.626.8332 Saturday, October 28, 9–11 a.m., Science-Engineering Library [email protected] All alumni and friends are welcome at our Homecoming EXHIBIT | Opens August 7 celebration. -

Regional Oral History Off Ice University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California

Regional Oral History Off ice University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Richard B. Gump COMPOSER, ARTIST, AND PRESIDENT OF GUMP'S, SAN FRANCISCO An Interview Conducted by Suzanne B. Riess in 1987 Copyright @ 1989 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West,and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the University of California and Richard B. Gump dated 7 March 1988. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

The John and Anna Gillespie Papers an Inventory of Holdings at the American Music Research Center

The John and Anna Gillespie papers An inventory of holdings at the American Music Research Center American Music Research Center, University of Colorado at Boulder The John and Anna Gillespie papers Descriptive summary ID COU-AMRC-37 Title John and Anna Gillespie papers Date(s) Creator(s) Repository The American Music Research Center University of Colorado at Boulder 288 UCB Boulder, CO 80309 Location Housed in the American Music Research Center Physical Description 48 linear feet Scope and Contents Papers of John E. "Jack" Gillespie (1921—2003), Professor of music, University of California at Santa Barbara, author, musicologist and organist, including more than five thousand pieces of photocopied sheet music collected by Dr. Gillespie and his wife Anna Gillespie, used for researching their Bibliography of Nineteenth Century American Piano Music. Administrative Information Arrangement Sheet music arranged alphabetically by composer and then by title Access Open Publication Rights All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the American Music Research Center. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], John and Anna Gillespie papers, University of Colorado, Boulder Index Terms Access points related to this collection: Corporate names American Music Research Center - Page 2 - The John and Anna Gillespie papers Detailed Description Bibliography of Nineteenth-Century American Piano Music Music for Solo Piano Box Folder 1 1 Alden-Ambrose 1 2 Anderson-Ayers 1 3 Baerman-Barnes 2 1 Homer N. Bartlett 2 2 Homer N. Bartlett 2 3 W.K. Bassford 2 4 H.H. Amy Beach 3 1 John Beach-Arthur Bergh 3 2 Blind Tom 3 3 Arthur Bird-Henry R. -

Gaceta Oficial Del Distrito Federal

GACETA OFICIAL DEL DISTRITO FEDERAL Órgano del Gobierno del Distrito Federal DÉCIMA QUINTA ÉPOCA 21 DE ENERO DE 2005 No. 9 Í N D I C E ADMINISTRACIÓN PÚBLICA DEL DISTRITO FEDERAL SECRETARÍA DE FINANZAS ♦ PARTICIPACIONES ENTREGADAS A LOS ÓRGANOS POLÍTICO-ADMINISTRATIVOS DE LOS FONDOS GENERAL DE PARTICIPACIONES Y DE FOMENTO MUNICIPAL EN EL CUARTO TRIMESTRE DEL AÑO 2004 2 SECRETARÍA DE SEGURIDAD PÚBLICA ♦ RELACIÓN DE PRESTADORES DE SERVICIOS DE SEGURIDAD PRIVADA QUE HAN ACREDITADO DOCUMENTALMENTE LOS REQUISITOS QUE ESTABLECE LA LEY Y REGLAMENTO EN LA MATERIA PARA OBTENER AUTORIZACIÓN Y REGISTRO Y HAN SATISFECHO EL PROCESO DE REVISIÓN 3 DELEGACIÓN COYOACÁN ♦ FE DE ERRATAS 119 CONVOCATORIAS Y LICITACIONES 120 SECCIÓN DE AVISOS ♦ GRUPO COMERCIAL EN COMUNICACIÓN, S.A. DE C.V. 127 ♦ INMOBILIARIA PEDRO DE ALVARADO, S.A. DE C.V. 128 ♦ FIASMEX, S.A. DE C.V. 129 ♦ PIROTE, S.A. 129 ♦ E D I C T O S 130 2 GACETA OFICIAL DE DISTRITO FEDERAL 21 de enero de 2005 ADMINISTRACIÓN PÚBLICA DEL DISTRITO FEDERAL SECRETARÍA DE FINANZAS PARTICIPACIONES ENTREGADAS A LOS ÓRGANOS POLÍTICO-ADMINISTRATIVOS DE LOS FONDOS GENERAL DE PARTICIPACIONES Y DE FOMENTO MUNICIPAL EN EL CUARTO TRIMESTRE DEL AÑO 2004 ARTURO HERRERA GUTIÉRREZ, Secretario de Finanzas del Distrito Federal, con fundamento en los artículos 15, fracción VIII, 16, fracción IV y 30, fracción XIV, de la Ley Orgánica de la Administración Pública del Distrito Federal; 337, 374, 435, 458, 469, fracción I, 478 y 488, del Código Financiero del Distrito Federal; 6°, último párrafo, de la Ley de Coordinación Fiscal; -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

THE 53Rd INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE on ELECTRON, ION, and PHOTON BEAM TECHNOLOGY & NANOFABRICATION

THE 53rd INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE on ELECTRON, ION, and PHOTON BEAM TECHNOLOGY & NANOFABRICATION Marco Island Marriott Resort, Golf Club and Spa Marco Island, Florida May 26 – May 29, 2009 Co-sponsored by: The American Vacuum Society in cooperation with: The Electron Devices Society of the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers and The Optical Society of America Conference at a Glance Conference at a Glance CONFERENCE ORGANIZATION CONFERENCE CHAIR Stephen Chou, Princeton University PROGRAM CHAIR Elizabeth Dobisz, Hitachi Global Storage Technologies MEETING PLANNER Melissa Widerkehr, Widerkehr and Associates STEERING COMMITTEE R. Blakie, University of Canterbury A. Brodie, KLA-Tencor S. Brueck, University of New Mexico S. Chou, Princeton University E. Dobisz, Hitachi Global Storage Technologies M. Feldman, Louisiana State University C. Hanson, SPAWAR J.A. Liddle, NIST F. Schellenberg, Mentor Graphics G. Wallraff, IBM ADVISORY COMMITTEE Ilesanmi Adesida, Robert Bakish, Alec N. Broers, John H. Bruning, Franco Cerrina, Harold Craighead, K. Cummings, N. Economou, D. Ehrlich, R. Englestad, T. Everhart, M. Gesley, T. Groves, L. Harriott, M. Hatzakis, F. Hohn, R. Howard, E. Hu, J. Kelly, D. Kern, R. Kubena, R. Kunz, N. MacDonald, C. Marrian, S. Matsui, M. McCord, D. Meisburger, J. Melngailis, A. Neureuther, T. Novembre, J. Orloff, G. Owen, S. Pang, R.F. Pease, M. Peckerar, H. Pfeifer, J. Randall, D. Resnick, M. Schattenburg, H. Smith, L. Swanson, D. Tennant*, L. Thompson, G. Varnell, R. Viswanathan, A. Wagner, J. Wiesner, C. Wilkinson, A. Wilson, Shalom Wind, E. Wolfe *Financial Trustee COMMERCIAL SESSION Alan Brodie, KLA Tencor Rob Illic, Cornell University Reginald Farrow, New Jersey Institute of Technology Brian Whitehead, Raith PROGRAM COMMITTEE & SECTION HEADS Lithography E- Beam Optical Lithography A. -

Forsyth Technical Community College Commencement 2015

Forsyth Technical Community College Commencement 2015 Lawrence Joel Veterans Memorial Coliseum 2825 University Parkway Winston-Salem, North Carolina Thursday, May 7, 2015 5:00 p.m. Forsyth Technical Community College Commencement 2015 Lawrence Joel Veteran’s Memorial Coliseum 2825 University Parkway Winston-Salem, North Carolina Thursday, May 7, 2015 5 p.m. Forsyth Technical Community College Board of Trustees Edwin L. Welch, Jr. Chair Ann Bennett-Phillips Nancy W. Dunn Jeffrey R. McFadden Amanda Boston A. Edward Jones R. Alan Proctor SGA President Andrea D. Kepple Vice Chair John M. Davenport, Jr. Arnold G. King Kenneth M. Sadler; D.D.S. Tammy L. Duggins Paul M. Wiles Forsyth Technical Community College Board of Administration Dr. Gary M. Green President Dr. Jewel B. Cherry Mr. Alan K. Murdock Vice President Vice President Student Services Economic & Workforce Development Ms. Rachel M. Desmarais Ms. Mamie M. Sutphin Vice President Vice President Information Services Institutional Advancement Ms. Wendy R. Emerson Dr. Conley F. Winebarger Vice President Vice President Business Services Instructional Services 2015 Commencement Program Processional Presiding......................................................................................................................Dr. Gary M. Green President, Forsyth Technical Community College National Anthem .................................................................................................. Sonya Bennett-Brown Music Instructor, Humanities & Social Sciences Division Introduction of -

15Th Annual Student Research and Creativity Celebration, SUNY Buffalo State

I II III III I I I I I I I I 15th Annual Student Research and Creativity Celebration, SUNY Buffalo State I II III III I I I I I I I I Editor Jill K. Singer, Ph.D. Director, Office of Undergraduate Research Sponsored by Office of Undergraduate Research Office of Academic Affairs Research Foundation for SUNY/Buffalo State Cover Design and Layout: Carol Alex The following individuals and offices are acknowledged for their many contributions: Sean Fox, Ellofex, Inc. Tom Coates, Events Management, and staff, especially Maryruth Glogowski, Director, E.H. Butler Library, Mary Beth Wojtaszek and the library staff Department and Program Coordinators (identified below) Carole Schaus, Office of Undergraduate Research Kaylene Waite, Computer Graphics Specialist and very special thanks to Carol Alex, Center for Bruce Fox, Photographer Development of Human Services Department and Program Coordinators for the Fifteenth Annual Student Research and Creativity Celebration Lisa Anselmi, Anthropology Bill Lin, Computer Information Systems Kyeonghi Baek, Political Science Dan MacIsaac, Physics Saziye Bayram, Mathematics Candace Masters, Art Education Carol Beckley, Theater Amy McMillan, Biology Lynn Boorady, Fashion and Textile Technology Susan McMillen, Faculty Development Betty Cappella, Higher Education Administration Michaelene Meger, Exceptional Education Louis Colca, Social Work Michael Niman, Communication Michael Cretacci, Criminal Justice Jill Norvilitis, Psychology Carol DeNysschen, Dietetics and Nutrition Kathleen O’Brien, Hospitality and Tourism