JINNAH Creator of Pakistan by HECTOR BOLITHO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dispute Over Bombay Mansion Highlights Indo-Pakistani Tensions

Page 1 18 of 22 DOCUMENTS The Washington Post November 9, 1983, Wednesday, Final Edition Dispute Over Bombay Mansion Highlights Indo-Pakistani Tensions BYLINE: By William Claiborne, Washington Post Foreign Service SECTION: First Section; General News; A27 LENGTH: 741 words DATELINE: NEW DELHI, Nov. 8, 1983 A dispute over possession of the former Bombay home of Pakistan's founder, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, coupled with continuing cross allegations of interference in each other's internal affairs, has raised tensions between India and Pakistan at a time when efforts to normalize relations between the two former enemies have ground to a standstill. While the rancor over Jinnah's palatial mansion is little more than a sideshow to sporadically turbulent Indo-Pakistan relations, diplomats on both sides agreed that it is symptomatic of a fundamental lack of trust that stems from the partition of the Subcontinent in 1947 and the successive wars between the two new nations. "There seem to be second thoughts on the Indian side about normalizing relations. Maybe they think Pakistani President Mohammed Zia ul-Haq is going to be forced out, and that there's no point in talking to him now," said a Pakistani diplomat, referring to Zia's problems in controlling violent opposition protests in Sind Province. Pakistani officials said that because of the dispute over Jinnah's house, which Pakistan planned to use as a residence of the new consul general in Bombay, plans to open a consulate in India's second largest city have been scrapped. The house that Jinnah used as a base in the early days of India's independence struggle had been promised by India to Pakistan in 1976, when diplomatic relations were resumed after having been broken in the 1971 war. -

My Memories of M a Jinnah

My memories of M A Jinnah R C Mody is a postgraduate in Economics and a Certificated Associate of the Indian Institute of Bankers. He studied at Raj Rishi College (Alwar), Agra College (Agra), and Forman Christian College (Lahore). For over 35 years, he worked for the Reserve Bank of India, where he headed several all-India departments, and was also Principal of the RBI Staff College. Now (2011) 84 years old, he is engaged in social work, reading, writing, and travelling. He lives in New Delhi with his wife. His email address is [email protected]. R C Mody uring pre-independence days, there was a craze among youngsters to boast about how many leaders of the independence movement they had seen. Everyone wanted to excel the other in D this regard. Not only the number but also the stature of the leader mattered. I had little to report. I had grown up and spent my early boyhood in Alwar, a Princely state. Leaders of national stature rarely visited Alwar, as the freedom movement was confined largely to British India. I had not seen practically any well-known leader in person till I was in my mid-teens. When I went to college in Agra in July 1942, I hoped to meet national leaders because Agra was a leading city of British India. Alas! The Quit India movement commenced within a month. And the British government responded by locking up all the prominent leaders whom I looked forward to see. For months, we were not even aware where they were confined. -

61 in This Book, the Author Has Given the Hfe Sketch of the Distinguish Personahties, Who Supported the Augarh Movement and Made

61 In this book, the author has given the Hfe sketch of the distinguish personahties, who supported the AUgarh Movement and made efforts for the betterment of the MusHm Community. The author highlighting the importance of the Aligarh Muslim University said that "it is the most prestigious intellectual and cultural centre of Indian Muslims". He also explained in this book that Hindus easily adopted the western education. As for Hindus, the advent of the Britishers and their emergence as the rulers were just a matter of change from one master to another. For them, the Britishers and Muslims were both conquerors. But for the Muslims it was a matter of becoming ruled instead of the ruler. Naqvi, Noorul Hasan (2001) wrote a book in Urdu entitled "Mohammadan College Se Muslim University Tak (From Mohammadan College to Muslim University)".^^ In this book he wrote in brief about the life and works of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, He gave a brief description about the supporters of Sir Syed and Aligarh Movement such as Mohsin-ul-Mulk, Viqar-ul-Mulk, Altaf Husain Hali, Maulana Shibli Nomani, Moulvi Samiullah Khan, Jutice Mahmud, Raja Jai Kishan Das and Maulvi ZakauUah Khan, etc. The author also wrote about the Aligarh Movement, the Freedom Movement and the educational planning of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan. A historical development of AMU has also been made. The author has also given in brief about the life of some of the important benefactors of the university such as His Highness Sir Agha Khan, Her Majestry Nawab Sultan Jahan Begum, His Holiness Maharaja Mohammad Ali Khan of . -

CENTRAL INFORMATION COMMISSION (Under Sec 19 of the Right to Information Act 2005) B Block, August Kranti Bhawan, New Delhi 1100065

Appeal No.CIC/OK/A/2007/001392 CENTRAL INFORMATION COMMISSION (Under Sec 19 of the Right to Information Act 2005) B Block, August Kranti Bhawan, New Delhi 1100065 Name of the Appellant - Shri Nusli Wadia, Mumbai Name of the Public Authority - Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) Respondent South Block, New Delhi-110011 Date of Hearing 21.12.2007 Date of Decision 16.01.2008 Facts: 1. By an application of 6-6-’07 submitted on 12-6-07 Shri Nusli Wadia of Mumbai sought the following information from the CPIO, MEA (i) “documents, notes of meeting and file notes relating to or arising out of the letter dated July 06, 2001 sent by Mrs. Dina Wadia to the Hon’ble Prime Minister of India including notes of or documents relating to the discussion between the Hon’ble Prime Minister of India and the Hon’ble External Affairs Minister referred to in the letter no. 757/PSBPM/2001 dated July 13, 2001; (ii) copies of all documents, notes of meetings, file notings, including inter-ministerial notes, advice sought or given including all approvals, proposals, recommendations from the concerned ministers/ICCR including those to and from the Hon’ble Prime Minister; (iii) minutes of meetings with the Hon’ble Prime Minister and any other Ministers/Officials on the matter; and (iv) Opinions given by any authority or person, including legal advice.” 2. To this he received a response on 12-7-07 that the information from CPIO Shri A.K. Nag, JS, (Welfare & Information) was being collected and sought more 1 time. -

In Quest of Jinnah

Contents Acknowledgements xiii Preface xv SHARIF AL MUJAHID Introduction xvii LIAQUAT H. MERCHANT, SHARIF AL MUJAHID Publisher's Note xxi AMEENA SAIYID SECTION 1: ORIGINAL ESSAYS ON JINNAH 1 1. Mohammad Ali Jinnah: One of the Greatest Statesmen of the Twentieth Century 2 STANLEY WOLPERT 2. Partition and the Birth of Pakistan 4 JOHN KENNETH GALBRAITH 3. World of His Fathers 7 FOUAD AJAMI 4. Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah 12 LIAQUAT H. MERCHANT 5. Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah: A Historian s Perspective 17 S.M. BURKE 6. Jinnah: A Portrait 19 SHARIF AL MUJAHID 7. Quaid-i-Azam's Personality and its Role and Relevance in the Achievement of Pakistan 32 SIKANDAR HAYAT 8. Mohammad Ali Jinnah 39 KULDIP NAYAR 9. M.A. Jinnah: The Official Biography 43 M.R. KAZIMI 10. The Official Biography: An Evaluation 49 SHARIF AL MUJAHID 11. Inheriting the Raj: Jinnah and the Governor-Generalship Issue 59 AYESHA JALAL 12. Constitutional Set-up of Pakistan as Visualised by Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah 76 S. SHARIFUDDIN PIRZADA 13. Jinnah—Two Perspectives: Secular or Islamic and Protector General ot Minorities 84 LIAQUAT H. MERCHANT 14. Jinnah on Civil Liberties 92 A.G. NOORANl 15. Jinnah and Women s Emancipation 96 SHARIF AL MUJAHID 16. Jinnah s 'Gettysburg Address' 106 AKBAR S. AHMED 17. The Two Saviours: Ataturk and Jinnah 110 MUHAMMAD ALI SIDDIQUI 18. The Quaid and the Princely States of India 115 SHAHARYAR M. KHAN 19. Reminiscences 121 JAVID IQBAL 20. Jinnah as seen by Sir Sultan Muhammad Shah,Aga Khan III 127 LIAQUAT H. -

Dawood Hercules Corporation Limited List of Unclaimed Dividend / Shares

Dawood Hercules Corporation Limited List of Unclaimed Dividend / Shares Unclaimed Unclaimed S.No FOLIO NAME CNIC / NTN Address Shares Dividend 22, BAHADURABADROAD NO.2, BLOCK-3KARACHI-5 1 38 MR. MOHAMMAD ASLAM 00000-0000000-0 5,063 558/5, MOORE STREETOUTRAM ROADKARACHI 2 39 MR. MOHAMMAD USMAN 00000-0000000-0 5,063 FLAT NO. 201, SAMAR CLASSIC,KANJI TULSI DAS 3 43 MR. ROSHAN ALI 42301-1105360-7 STREET,PAKISTAN CHOWK, KARACHI-74200.PH: 021- 870 35401984MOB: 0334-3997270 34, AMIL COLONY NO.1SHADHU HIRANAND 4 47 MR. AKBAR ALI BHIMJEE 00000-0000000-0 ROADKARACHI-5. 5,063 PAKISTAN PETROLEUM LIMITED3RD FLOOR, PIDC 5 48 MR. GHULAM FAREED 00000-0000000-0 HOUSEDR. ZIAUDDIN AHMED ROADKARACHI. 756 C-3, BLOCK TNORTH NAZIMABADKARACHI. 6 63 MR. FAZLUR RAHMAN 00000-0000000-0 7,823 C/O. MUMTAZ SONS11, SIRAJ CLOTH 7 68 MR. AIJAZUDDIN 00000-0000000-0 MARKETBOMBAY BAZARKARACHI. 5,063 517-B, BLOCK 13FEDERAL 'B' AREAKARACHI. 8 72 MR. S. MASOOD RAZA 00000-0000000-0 802 93/10-B, DRIGH ROADCANTT BAZARKARACHI-8. 9 81 MR. TAYMUR ALI KHAN 00000-0000000-0 955 BANK SQUARE BRANCHLAHORE. 10 84 THE BANK OF PUNJAB 00000-0000000-0 17,616 A-125, BLOCK-LNORTH NAZIMABADKARACHI-33. 11 127 MR. SAMIULLAHH 00000-0000000-0 5,063 3, LEILA BUILDING, ABOVE UBLARAMBAGH ROAD, 12 150 MR. MUQIMUDDIN 00000-0000000-0 PAKISTAN CHOWKKARACHI-74200. 5,063 ZAWWAR DISPENSARYOPP. GOVT. COLLEGE FOR 13 152 MRS. KARIMA ABDUL RAHIM 00000-0000000-0 WOMENFRERE ROADKARACHI. 5,063 ZAWWAR DISPENSARYOPP. GOVT COLLEGE FOR 14 153 DR. ABDUL RAHIM GANDHI 00000-0000000-0 WOMENFRERE ROADKARACHI. -

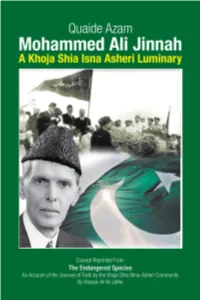

Quide Azam Monograph V3

Quaide Azam Mohammed Ali Jinnah: A Khoja Shia Ithna Asheri Luminary ndia became Independent in 1947 when the country was divided as India and Pakistan. Four men played a significant role in I shaping the end of British rule in India: The British Viceroy, Lord Louis Mountbatten, the Indian National Congress leaders Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, and the Muslim League leader, Mohamed Ali Jinnah. Jinnah led the Muslims of India to create the largest Muslim State in the world then. In 1971 East Pakistan separated to emerge as Bangladesh. Much has been written about the first three in relative complimentary terms. The fourth leading player, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, founding father of Pakistan, lovingly called Quaid-e-Azam (the great leader) has been much maligned by both Indian and British writers. Richard Attenborough's hugely successful film Gandhi has also done much to portray Jinnah in a negative light. Excerpt from Endangered Species | 4 The last British Viceroy, Lord Louis Mountbatten, spared no adjectives in demonizing Jinnah, and his views influenced many writers. Akber S. Ahmed quotes Andrew Roberts from his article in Sunday Times, 18 August,1996: “Mountbatten contributed to the slander against Jinnah, calling him vain, megalomaniacal, an evil genius , a lunatic, psychotic case and a bastard, while publicly claiming he was entirely impartial between Jinnah’s Pakistan and Nehru’s India. Jinnah rose magisterially above Mountbatten’s bias, not even attacking the former Viceroy when, as Governor General of India after partition, Mountbatten tacitly condoned India’s shameful invasion of Kashmir in October 1947.”1 Among recent writers, Stanley Wolport with his biography: Jinnah of Pakistan, and Patrick French in his well researched Freedom or Death analyzing the demise of the British rule in India come out with more balanced portrayal of Jinnah - his role in the struggle for India’s independence and in the creation of Pakistan. -

Backup of FLYER 2021-4

INTERNATIONAL FEBRUARY 2021 Turkish Airlines to fly YG Cargo airlines starts from SIAL freighter service to Pakistan The mother of all motorways FEBRUARY 2021 - 3 I n t e r n a t i o n a l a v i a t i o n f New By Abdul Sattar Azad Phone 34615924 Fax 34615924 Printed by Sardar Sons 4 - FEBRUARY 2021 Vol 28 FEBRUARY 2021 No.05 ICAO updates global tourism 06 PIA sets new rules for crew: passports held, mobility restricted 08 IATA welcomes opening of new terminal at Bahrain International Airport 08 Turkish Airlines to fly from SIAL, Qatar Airways and Gulf Air to resume flight operation 09 Gulf Air moves into the new terminal at Bahrain International Airport 09 08 CAA to outsource pilots licensing exams to UK 10 IATA urges support for common european digital vaccination certificate 10 It's time for airline loyalty programs to add value 11 Gulf Air takes another Airbus A321LR 12 Why air cargo prices will not be back to 'normal' by 2023 14 China authorities extend anal Covid-19 tests for passengers arriving from abroad 15 Qatar-Saudi border reopens after thaw 17 FIA to attach properties owned by Shaheen Air 18 Walton airport likely to be shifted 19 IATA: 2020 was the worst year in history for air travel demand 21 Gulf Air to start European long-haul flights with Airbus A321LR 23 Emirates' self check-in screens are now fully touchless 30 European Plan for Aviation Safety 2021-2025 published 30 27 Lufthansa cuts first class on all US routes until at least May 32 Multan's mangoes and multinationals 34 Utilise Gwadar Port for transit trade with Kabul 35 Textile exports reached historic high in Dec. -

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Mohammad Raisur Rahman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India Committee: _____________________________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________________________ Cynthia M. Talbot _____________________________________ Denise A. Spellberg _____________________________________ Michael H. Fisher _____________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India by Mohammad Raisur Rahman, B.A. Honors; M.A.; M.Phil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the fond memories of my parents, Najma Bano and Azizur Rahman, and to Kulsum Acknowledgements Many people have assisted me in the completion of this project. This work could not have taken its current shape in the absence of their contributions. I thank them all. First and foremost, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my advisor Gail Minault for her guidance and assistance. I am grateful for her useful comments, sharp criticisms, and invaluable suggestions on the earlier drafts, and for her constant encouragement, support, and generous time throughout my doctoral work. I must add that it was her path breaking scholarship in South Asian Islam that inspired me to come to Austin, Texas all the way from New Delhi, India. While it brought me an opportunity to work under her supervision, I benefited myself further at the prospect of working with some of the finest scholars and excellent human beings I have ever known. -

Picture of Muslim Politics in India Before Wavell's

Muhammad Iqbal Chawala PICTURE OF MUSLIM POLITICS IN INDIA BEFORE WAVELL’S VICEROYALTY The Hindu-Muslim conflict in India had entered its final phase in the 1940’s. The Muslim League, on the basis of the Two-Nation Theory, had been demanding a separate homeland for the Muslims of India. The movement for Pakistan was getting into full steam at the time of Wavell’s arrival to India in October 1943 although it was opposed by an influential section of the Muslims. This paper examines the Muslim politics in India and also highlights the background of their demand for a separate homeland. It analyzes the nature, programme and leadership of the leading Muslim political parties in India. It also highlights their aims and objectives for gaining an understanding of their future behaviour. Additionally, it discusses the origin and evolution of the British policy in India, with special reference to the Muslim problem. Moreover, it tries to understand whether Wavell’s experiences in India, first as a soldier and then as the Commander-in-Chief, proved helpful to him in understanding the mood of the Muslim political scene in India. British Policy in India Wavell was appointed as the Viceroy of India upon the retirement of Lord Linlithgow in October 1943. He was no stranger to India having served here on two previous occasions. His first-ever posting in India was at Ambala in 1903 and his unit moved to the NWFP in 1904 as fears mounted of a war with 75 76 [J.R.S.P., Vol. 45, No. 1, 2008] Russia.1 His stay in the Frontier province left deep and lasting impressions on him. -

The Role of Muttahida Qaumi Movement in Sindhi-Muhajir Controversy in Pakistan

ISSN: 2664-8148 (Online) Liberal Arts and Social Sciences International Journal (LASSIJ) https://doi.org/10.47264/idea.lassij/1.1.2 Vol. 1, No. 1, (January-June) 2017, 71-82 https://www.ideapublishers.org/lassij __________________________________________________________________ The Role of Muttahida Qaumi Movement in Sindhi-Muhajir Controversy in Pakistan Syed Mukarram Shah Gilani1*, Asif Salim1-2 and Noor Ullah Khan1-3 1. Department of Political Science, University of Peshawar, Peshawar Pakistan. 2. Department of Political Science, Emory University Atlanta, Georgia USA. 3. Department of Civics-cum-History, FG College Nowshera Cantt., Pakistan. …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Abstract The partition of Indian sub-continent in 1947 was a historic event surrounded by many controversies and issues. Some of those ended up with the passage of time while others were kept alive and orchestrated. Besides numerous problems for the newly born state of Pakistan, one such controversy was about the Muhajirs (immigrants) who were settled in Karachi. The paper analyses the factors that brought the relation between the native Sindhis and Muhajirs to such an impasse which resulted in the growth of conspiracy theories, division among Sindhis; subsequently to the demand of Muhajir Suba (Province); target killings, extortion; and eventually to military clean-up operation in Karachi. The paper also throws light on the twin simmering problems of native Sindhis and Muhajirs. Besides, the paper attempts to answer the question as to why the immigrants could not merge in the native Sindhis despite living together for so long and why the native Sindhis remained backward and deprived. Finally, the paper aims at bringing to limelight the role of Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM). -

Heritage List

LISTING GRADING OF HERITAGE BUILDINGS PRECINCTS IN MUMBAI Task II: Review of Sr. No. 317-632 of Heritage Regulation Sr. No. Name of Monuments, Value State of Buildings, Precincts Classification Preservation Typology Location Ownership Usage Special Features Date Existing Grade Proposed Grade Photograph 317Zaoba House Building Jagananth Private Residential Not applicable as the Not applicable as Not applicable as Not applicable as Deleted Deleted Shankersheth Marg, original building has been the original the original the original Kalbadevi demoilshed and is being building has been building has been building has been rebuilt. demoilshed and is demoilshed and is demoilshed and is being rebuilt. being rebuilt. being rebuilt. 318Zaoba Ram Mandir Building Jagananth Trust Religious Vernacular temple 1910 A(arc), B(des), Good III III Shankersheth Marg, architecture.Part of building A(cul), C(seh) Kalbadevi in stone.Balconies and staircases at the upper level in timber. Decorative features & Stucco carvings 319 Zaoba Wadi Precinct Precinct Along Jagannath Private Mixed Most features already Late 19th century Not applicable as Poor Deleted Deleted Shankershet Marg , (Residential & altered, except buildings and early 20th the precinct has Kalbadevi Commercial) along J. S. Marg century lost its architectural and urban merit 320 Nagindas Mansion Building At the intersection Private (Nagindas Mixed Indo Edwardian hybrid style 19th Century A(arc), B(des), Fair II A III of Dadasaheb Purushottam Patel) (Residential & with vernacular features like B(per), E, G(grp) Bhadkamkar Marg Commercial) balconies combined with & Jagannath Art Deco design elements Shankersheth & Neo Classical stucco Road, Girgaum work 321Jama Masjid Building Janjikar Street, Trust Religious Built on a natural water 1802 A(arc), A(cul), Good II A II A Near Sheikh Menon (Jama Masjid of (Muslim) source, displays Islamic B(per), B(des),E, Street Bombay Trust) architectural style.