Javier Francisco Muñoz Basols

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Editions 2013: Reviews and Listings of Recent Prints And

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas January – February 2014 Volume 3, Number 5 New Editions 2013: Reviews and Listings of Recent Prints and Editions from Around the World Dasha Shishkin • Crown Point Press • Fanoon: Center for Print Research • IMPACT8 • Prix de Print • ≤100 • News international fi ne ifpda print dealers association 2014 Calendar Los Angeles IFPDA Fine Print Fair January 15–19 laartshow.com/fi ne-print-fair San Francisco Fine Print Fair January 24–26 Details at sanfrancisco-fi neprintfair.com IFPDA Foundation Deadline for Grant Applications April 30 Guidelines at ifpda.org IFPDA Book Award Submissions due June 30 Guidelines at ifpda.org IFPDA Print Fair November 5– 9 Park Avenue Armory, New York City More at PrintFair.com Ink Miami Art Fair December 3–7 inkartfair.com For IFPDA News & Events Visit What’s On at ifpda.org or Subscribe to our monthly events e-blast Both at ifpda.org You can also follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram! The World’s Leading Experts www.ifpda.org 250 W. 26th St., Suite 405, New York, NY 10001-6737 | Tel: 212.674.6095 | [email protected] Art in Print 2014.indd 1 12/6/13 4:22 PM January – February 2014 In This Issue Volume 3, Number 5 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Being There Associate Publisher Kate McCrickard 4 Julie Bernatz Welcome to the Jungle: Violence Behind the Lines in Three Suites of Prints by Managing Editor Dasha Shishkin Dana Johnson New Editions 2013 Reviews A–Z 10 News Editor Isabella Kendrick Prix de Print, No. -

90 Av 100 Ålänningar Sågar Upphöjd Korsning Säger Nej

Steker crépe på Lilla holmen NYHETER. Fransmannen Zed Ziani har fl yttat sitt créperie till Lilla holmen i Mariehamn och för första gången på många år fi nns det servering igen på friluftsområdet. Både salta och söta crépe, baguetter och kaffe fi nns på menyn i det lilla caféet med utsikt över fågeldammen Lördag€ SIDAN 18 12 MAJ 2007 NR 100 PRIS 1,20 och Slemmern. 90 av 100 ålänningar sågar upphöjd korsning Säger nej. Annette Gammals deltog i Nyans gatupejling om Ålandsvägens upphöjda korsning- ar. Men planerarna har politikernas uppdrag att se Men frågan är: Vems bekvämlighet är viktigast? till också den lätta trafi kens intressen. NYHETER. Ska alla trafi kanter – bilister, – Jag tycker mig känna igen trafi kplane- ålänningarna kanske har svårare än andra att – Jag hatar bumpers, sa Ingmar Håkansson cyklister, fotgängare och gamla med rullator ringsdiskussionen från 1960-talet när devisen ge avkall på bilbekvämligheten. från Lumparland som har jobbat 26 år som – behandlas jämlikt i stadstrafi ken? var att bilarna ska fram, allt ska ske på bilis- – Åland är väldigt bilberoende. Men man yrkeschaufför. Ja, säger planerarna i Mariehamn. Politi- ternas villkor och de oskyddade och sårbara måste ändå tänka på att också andra har rätt 90 personer svarade nej på frågan om de vill kerna har godkänt de styrdokument som de trafi kanterna får klara sig bäst de kan, säger till en säker trafi kmiljö. ha upphöjda korsningar, tio svarade ja. baserar ombyggnaden av Ålandsvägen på. tekniska nämndens ordförande Folke Sjö- Känslorna var starka då Nyan i går pejlade – Jag har barn som skall gå över Ålandsvä- Det som nu har hänt är att en del politiker lund. -

THE MISMEASURE of MAN Revised and Expanded

BY STEPHEN JAY GOULD IN NORTON PAPERBACK EVER SINCE DARWIN Reflections in Natural History THE PANDA'S THUMB More Reflections in Natural History THE MISMEASURE OF MAN Revised and Expanded HEN'S TEETH AND HORSE'S TOES Further Reflections in Natural History THE FLAMINGO'S SMILE Reflections in Natural History AN URCHIN IN THE STORM Essays about Books and Ideas ILLUMINATIONS A Bestiary (with R. W. Purcell) WONDERFUL LIFE The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History BULLY FOR BRONTOSAURUS Reflections in Natural History FINDERS, KEEPERS Treasures amd Oddities of Natural History Collectors from Peter the Great to Louis Agassiz (with R. W. Purcell) THE MISMEASURE OF MAN To the memory of Grammy and Papa Joe, who came, struggled, and prospered, Mr. Goddard notwithstanding. Contents Acknowledgments 15 Introduction to the Revised and Expanded Edition: Thoughts at Age Fifteen 19 The frame of The Mismeasure of Man, 19 Why revise The Mismeasure of Man after fifteen years?, 26 Reasons, history and revision of The Mismeasure of Man, 36 2. American Polygeny and Craniometry before Darwin: Blacks andlndians as Separate, Inferior Species Cfolj 62 A shared context of culture, 63 Preevolutionary styles of scientific racism: monogenism and polygenism, 71 Louis Agassiz—America's theorist of polygeny, 74 Samuel George Morton—empiricist of polygeny, 82 The case of Indian inferiority: Crania Americana The case of the Egyptian catacombs: Crania Aegyptiaca The case of the shifting black mean The final tabulation of 1849 IO CONTENTS Conclusions The American school and -

WEE19 – Reviewed by London Student

West End Eurovision 2019: A Reminder of the Talent and Supportive Community in the Theatre Industry ARTS, THEATRE Who doesn’t love Eurovision? The complete lack of expectation for any UK contestant adds a laissez faire tone to the event that works indescribably well with the zaniness of individual performances. Want dancing old ladies? Look up Russia’s 2012 entrance. Has the chicken dance from primary school never quite left your consciousness? Israel in 2018 had you covered. Eurovision is camp and fun, and we need more of that these days… cue West End Eurovision, a charity event where the casts from different shows compete with previous Eurovision songs to win the approval of a group of judges and the audience. The seven shows competing were: Only Fools and Horses, Everybody’s Talking About Jamie, Aladdin, Mamma Mia!, Follies, The Phantom of the Opera, and Wicked. Each cast performed for four judges – Amber Davies, Bonnie Langford, Wayne Sleep, and Tim Vincent – following a short ident. Quite what these were for I’m not sure was explained properly to the cast: are they adverts for their shows (Everybody’s Talking About Jamie), adverts for the song they’re to perform (Phantom) or adverts for Eurovision generally (Mamma Mia!)? I don’t know, but they were all amusing and a good way to introduce each act. The cast of Only Fools and Horses opened the show, though they unfortunately came last in the competition, a less-than jubly result. That said, with sparkling costumes designed by Lisa Bridge, the performance of ‘Dancing Lasha Tumbai’, first performed by Ukraine in 2007, was certainly in the spirit of Eurovision and made for a sound opening number. -

Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE LIBRARIAN OF CONGRESS FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING SEPTEMBER 30, 2002 Library of Congress Photo Credits Independence Avenue, SE Photographs by Anne Day (cover), Washington, DC Michael Dersin (pages xii, , , , , and ), and the Architect of the For the Library of Congress Capitol (inside front cover, page , on the World Wide Web, visit and inside back cover). <www.loc.gov>. Photo Images The annual report is published through Cover: Marble mosaic of Minerva of the Publishing Office, Peace, stairway of Visitors Gallery, Library Services, Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building. Washington, DC -, Inside front cover: Stucco relief In tenebris and the Public Affairs Office, lux (In darkness light) by Edward J. Office of the Librarian, Library of Congress, Holslag, dome of the Librarian’s office, Washington, DC -. Thomas Jefferson Building. Telephone () - (Publishing) Page xii: Library of Congress or () - (Public Affairs). Commemorative Arch, Great Hall. Page : Lamp and balustrade, main entrance, Thomas Jefferson Building. Managing Editor: Audrey Fischer Page : The figure of Neptune dominates the fountain in front of main entrance, Thomas Jefferson Building. Copyediting: Publications Professionals Page : Great Hall entrance, Thomas Indexer: Victoria Agee, Agee Indexing Jefferson Building. Production Manager: Gloria Baskerville-Holmes Page : Dome of Main Reading Room; Assistant Production Manager: Clarke Allen murals by Edwin Blashfield. Page : Capitol dome from northwest Library of Congress pavilion, Thomas Jefferson Building; Catalog Card Number - mural “Literature” by William de - Leftwich Dodge. Key title: Annual Report of the Librarian Page : First floor corridor, Thomas of Congress Jefferson Building. Inside back cover: Stucco relief Liber delectatio animae (Books, the delight of the soul) by Edward J. -

Polish American and Additional Entry Offices

POLONIA CONGRATULATES POLISH PRESIDENTPOLISH IN NEW AMERICAN YORK — JOURNAL PAGE 3 • NOVEMBER 2015 www.polamjournal.com 1 PERIODICAL POSTAGE PAID AT BOSTON, NEW YORK NEW BOSTON, AT PAID PERIODICAL POSTAGE POLISH AMERICAN OFFICES AND ADDITIONAL ENTRY DEDICATED TO THE PROMOTION AND CONTINUANCE OF POLISH AMERICAN CULTURE JOURNAL REMEMBERING PULASKI AND “THE BIG BURN” ESTABLISHED 1911 NOVEMBER 2015 • VOL. 104, NO. 11 | $2.00 www.polamjournal.com PAGE 16 POLAND MAY SUE AUTHOR GROSS •PASB TILE CAMPAIGN UNVEILING•“JEDLINIOK” TOURS THE EASTERN UNITED STATES HEPI FĘKSGIWYŃG! • A LOOK AT POLAND’S LUTHERANS • FR. MAKA ENLISTS IN NAVY • NOVEMBER HOLIDAYS DO WIDZENIA OR WITAMY AMERIKA? • FATHER LEN’S POLISH CHRISTMAS LEGACY • WIGILIA FAVORITES MADE EASY Newsmark Makes First US Visit Fired Investigator Says US SUPPLY BASES IN POLAND. Warsaw and Washing- House Probe Is Partisan ton have reached agreement on the location of fi ve U.S. WASHINGTON — A The move military supply bases in Poland. The will be established former investigator for the d e - e m - in and around existing Polish military bases Łask, Draws- House Select Committee on phasized ko Pomorskie, Skwierzyna, Ciechanów and Choszczno. PHOTO: RADIO POLSKA Benghazi says he was unlaw- o t h e r Tanks, armored combat vehicles and other military equip- fully fi red in part because he agencies ment will form part of NATO’s quick-reaction spearhead. sought to conduct a compre- involved Siting the storage bases in Poland is expected to facilitate hensive probe into the deadly with the swift mobilization in the event of an attack. The project attacks on the U.S. -

Polish Jokes About Americans I C a E

I n v e s t i g a t i o n e s L i n g u i s t Polish Jokes about Americans i c a e , Dorota Brzozowska v o l . X I , Institute of Polish Language, University of Opole P o z ul. Oleska 48, 45-052 Opole, POLAND n a ń , [email protected] D e c e m b e r 2 0 Abstract 0 4 The objective of the present paper is to analyze the character of Polish jokes about Americans and to find out what these jokes say about Poles. The latter question results from the assumption that stereotypes reveal more about those who propagate them than about those who allegedly represent particular traits. The popularity of Americans is a certain novelty in contemporary Polish jokes and this fact could be interpreted as another element in the processes of so-called McDonaldization. The texts are presented by the chronology of events they refer to. Americans are perceived by Poles as the enemies of the Russians, and so as a positive protagonist, a symbol of the high standard of living and an embodiment of the dream of success and freedom. Wide open spaces and big American cities, cowboys, Indians, Hollywood and Coca Cola are other symbols frequently occurring in jokes. AIDS and drug addictions are also supposed to be the products of America altogether with American right to carry arms, litigiousness and death penalty. Another feature of the Americans readily exploited by scoffers is a relatively short history and the hypocrisy of American political correctness. -

Friedrich A. Von Hayek Papers, Date (Inclusive): 1906-2005 Collection Number: 86002 Creator: Hayek, Friedrich A

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3v19n8zw No online items Register of the Friedrich A. von Hayek Papers Processed by Linda Bernard and David Jacobs Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 1998, 2003, 2011 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Register of the Friedrich A. von 86002 1 Hayek Papers Register of the Friedrich A. von Hayek Papers Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Contact Information Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] Processed by: Linda Bernard and David Jacobs Date Completed: 1998, 2000, 2011 Encoded by: James Lake, ByteManagers using OAC finding aid conversion service specifications, and Elizabeth Phillips © 2011 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Friedrich A. von Hayek papers, Date (inclusive): 1906-2005 Collection number: 86002 Creator: Hayek, Friedrich A. von (Friedrich August), 1899-1992. Extent: 139 manuscript boxes, 8 oversize boxes, 23 card file boxes, 5 envelopes, 2 audio tapes, 16 videotape cassettes, digital files(66 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Diaries, correspondence, speeches and writings, notes, conference papers, conference programs, printed matter, sound recordings, and photographs, relating to laissez-faire economics and associated concepts of liberty, and especially to activities of the Mont Pèlerin Society. Most of collection also available on microfilm (91 reels). Sound use copies of sound recordings available. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Language: English and German. Access Collection is open for research. -

Maria José Alves Veiga O Humor Na Tradução Para Legendagem: Inglês/Português

Universidade de Aveiro Departamento de Línguas e Culturas 2006 Maria José Alves Veiga O Humor na Tradução para Legendagem: Inglês/Português Universidade de Aveiro Departamento de Línguas e Culturas 2006 Maria José Alves Veiga O Humor na Tradução para Legendagem: Inglês/Português dissertação apresentada à Universidade de Aveiro para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Doutor em Tradução, realizada sob a orientação científica da Professora Doutora Maria Teresa Costa Gomes Roberto, Professora Auxiliar do Departamento de Línguas e Culturas da Universidade de Aveiro Ao Zé Maria e à Helena Luísa. o júri presidente Prof. Dr.ª Celeste de Oliveira Coelho (Professora Catedrática da Universidade de Aveiro) Prof. Dr.ª Maria Teresa Costa Gomes Roberto (Professora Auxiliar da Universidade de Aveiro) Prof. Dr.ª Rosa Lídia Torres do Couto Coimbra e Silva (Professora Auxiliar da Universidade de Aveiro) Prof. Dr.ª Maria Teresa Murcho Alegre (Professora Auxiliar da Universidade de Aveiro) Prof. Dr.ª Isabel Cristina Costa Alves Ermida (Professora Auxiliar da Universidade do Minho) Prof. Dr.ª Josélia Maria Santos José Neves (Equiparada a Professora Adjunta do Instituto Politécnico de Leiria) Dr. Jorge Díaz Cintas (Principal Lecturer in Translation, da School of Arts – Roehampton University - London) agradecimentos Deixo expresso todo o meu apreço à minha orientadora, Professora Maria Teresa Roberto, pela confiança que depositou em mim, pelo constante estímulo científico, pelo inesgotável interesse e pela cuidada leitura, e subsequentes discussões, ao longo da realização deste trabalho. Estou grata não só à minha orientadora, como também ao Professor Doutor João Torrão por, através do Centro de Investigação do DLC, terem proporcionado a minha frequência em cursos de formação e a minha presença em encontros científicos que me permitiram crescer academicamente. -

Eurovision Karaoke

1 Eurovision Karaoke ALBANÍA ASERBAÍDJAN ALB 06 Zjarr e ftohtë AZE 08 Day after day ALB 07 Hear My Plea AZE 09 Always ALB 10 It's All About You AZE 14 Start The Fire ALB 12 Suus AZE 15 Hour of the Wolf ALB 13 Identitet AZE 16 Miracle ALB 14 Hersi - One Night's Anger ALB 15 I’m Alive AUSTURRÍKI ALB 16 Fairytale AUT 89 Nur ein Lied ANDORRA AUT 90 Keine Mauern mehr AUT 04 Du bist AND 07 Salvem el món AUT 07 Get a life - get alive AUT 11 The Secret Is Love ARMENÍA AUT 12 Woki Mit Deim Popo AUT 13 Shine ARM 07 Anytime you need AUT 14 Conchita Wurst- Rise Like a Phoenix ARM 08 Qele Qele AUT 15 I Am Yours ARM 09 Nor Par (Jan Jan) AUT 16 Loin d’Ici ARM 10 Apricot Stone ARM 11 Boom Boom ÁSTRALÍA ARM 13 Lonely Planet AUS 15 Tonight Again ARM 14 Aram Mp3- Not Alone AUS 16 Sound of Silence ARM 15 Face the Shadow ARM 16 LoveWave 2 Eurovision Karaoke BELGÍA UKI 10 That Sounds Good To Me UKI 11 I Can BEL 86 J'aime la vie UKI 12 Love Will Set You Free BEL 87 Soldiers of love UKI 13 Believe in Me BEL 89 Door de wind UKI 14 Molly- Children of the Universe BEL 98 Dis oui UKI 15 Still in Love with You BEL 06 Je t'adore UKI 16 You’re Not Alone BEL 12 Would You? BEL 15 Rhythm Inside BÚLGARÍA BEL 16 What’s the Pressure BUL 05 Lorraine BOSNÍA OG HERSEGÓVÍNA BUL 07 Water BUL 12 Love Unlimited BOS 99 Putnici BUL 13 Samo Shampioni BOS 06 Lejla BUL 16 If Love Was a Crime BOS 07 Rijeka bez imena BOS 08 D Pokušaj DUET VERSION DANMÖRK BOS 08 S Pokušaj BOS 11 Love In Rewind DEN 97 Stemmen i mit liv BOS 12 Korake Ti Znam DEN 00 Fly on the wings of love BOS 16 Ljubav Je DEN 06 Twist of love DEN 07 Drama queen BRETLAND DEN 10 New Tomorrow DEN 12 Should've Known Better UKI 83 I'm never giving up DEN 13 Only Teardrops UKI 96 Ooh aah.. -

C6076ff7ce484da269215574233

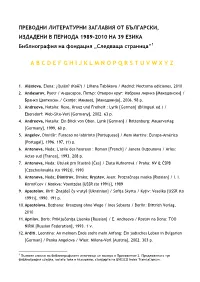

ПРЕВОДНИ ЛИТЕРАТУРНИ ЗАГЛАВИЯ ОТ БЪЛГАРСКИ, ИЗДАДЕНИ В ПЕРИОДА 1989-2010 НА 39 ЕЗИКА Библиография на фондация „Следваща страница”1 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z 1. Aléxieva, Elena: ¿Quién? (Кой?) / Liliana Tabákova / Madrid: Nocturna ediciones, 2010 2. Andasarov, Pyetr / Андасаров, Петър: Отворен круг: Избрана лирика [Македонски] / Бранко Цветкоски./ Скопје: Макавеј, [Македонија], 2006. 98 p. 3. Andreeva, Natalia: Rose, Kreuz und Freiheit : Lyrik [German] (Bilingual ed.) / Ebersdorf: Web-Site-Verl [Germany], 2002. 63 p. 4. Andreeva, Natalia: Ein Blick von Oben. Lyrik [German] / Rottenburg: Mauerverlag [Germany], 1999, 60 p. 5. Angelov, Dimităr: Furacao no labirinto [Portuguese] / Mem Martins: Europa-América [Portugal], 1996. 197, (1) p. 6. Antonova, Neda: L'asile des heureux : Roman [French] / Janeta Ouzounova / Arles: Actes sud [France], 1993. 208 p. 7. Antonova, Neda: Útulek pro šťastné [Čes] / Zlata Kufnerová / Praha: NV & ČSPB [Czechoslovakia (to 1992)], 1990 8. Antonova, Neda; Dimitrov, Dimko; Krystev, Asen: Prozračnaja maska [Russian] / I. I. Kormil'cev / Moskva: Voenizdat [USSR (to 1991)], 1989 9. Apostolov, Kiril: Znajdeš čy vratyš [Ukrainian] / Sofija Skyrta / Kyjiv: Veselka [USSR (to 1991)], 1990. 191 p. 10. Apostolova, Bozhana: Kreuzung ohne Wege / Ines Sebesta / Berlin: Dittrich Verlag, 2010 11. Aprilov, Boris: Priključenija Lisenka [Russian] / E. Andreeva / Rostov na Donu: TOO NIRiK [Russian Federation], 1993. 1 v. 12. Arditi, Leontina: An meinem Ende steht mein Anfang: Ein judisches Leben in Bulgarien [German] / Penka Angelova / Wien: Milena-Verl [Austria], 2002. 303 p. 1 Пълният списък на библиографските източници се намира в Приложение 2. -

Folklore Archive

Folklore Archive Papers, 1939-1995 43 linear feet Accession #1731 DALNET # OCLC # Selected materials from the Wayne State University Folklore Archive were transferred to the Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs in July of 1999 by the Archive’s director, Professor Janet Langlois, and opened for research in March of 2000. The Folklore Archive, established in 1939 by WSU English professors Emlyn Gardner and Thelma James, contains the oldest and largest record of urban folk traditions in the United States. At its core are thousands of student field research projects covering a broad range of topics. These projects typically consist of transcripts of oral interviews conducted by the students as part of their research. The collection is strong in modern industrial and occupational folklore, reflecting the rich ethnic diversity and work-oriented heritage of Detroit and southeastern Michigan. The Archive also contains oral histories (tapes and transcripts) and scholarly papers documenting Greek-American family life and the migration of Southern Appalachian whites to the metropolitan Detroit area and oral interviews with Pete Seeger and Irwin Silber of People’s Songs, Inc., which collected, published and promoted folksongs, particularly labor and protest songs. Important subjects in the collection: Afro-Americans--Medicine Afro-Americans--Michigan--Detroit--Social life and customs Ethnic groups--Humor Ethnic groups--Michigan--Detroit Ethnic groups--Religious life Folk-songs--United States German Americans--Michigan--Detroit--Social life and customs