ASEAN Biodiversity Outlook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

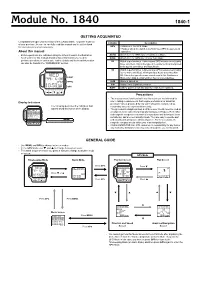

Module No. 1840 1840-1

Module No. 1840 1840-1 GETTING ACQUAINTED Congratulations upon your selection of this CASIO watch. To get the most out Indicator Description of your purchase, be sure to carefully read this manual and keep it on hand for later reference when necessary. GPS • Watch is in the GPS Mode. • Flashes when the watch is performing a GPS measurement About this manual operation. • Button operations are indicated using the letters shown in the illustration. AUTO Watch is in the GPS Auto or Continuous Mode. • Each section of this manual provides basic information you need to SAVE Watch is in the GPS One-shot or Auto Mode. perform operations in each mode. Further details and technical information 2D Watch is performing a 2-dimensional GPS measurement (using can also be found in the “REFERENCE” section. three satellites). This is the type of measurement normally used in the Quick, One-Shot, and Auto Mode. 3D Watch is performing a 3-dimensional GPS measurement (using four or more satellites), which provides better accuracy than 2D. This is the type of measurement used in the Continuous LIGHT Mode when data is obtained from four or more satellites. MENU ALM Alarm is turned on. SIG Hourly Time Signal is turned on. GPS BATT Battery power is low and battery needs to be replaced. Precautions • The measurement functions built into this watch are not intended for Display Indicators use in taking measurements that require professional or industrial precision. Values produced by this watch should be considered as The following describes the indicators that reasonably accurate representations only. -

Asia's Wicked Environmental Problems

ADBI Working Paper Series Asia’s Wicked Environmental Problems Stephen Howes and Paul Wyrwoll No. 348 February 2012 Asian Development Bank Institute Stephen Howes and Paul Wyrwoll are director and researcher, respectively, at the Development Policy Centre, Crawford School, Australian National University. This paper was prepared as a background paper for the Asian Development Bank (ADB)/Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI) study Role of Key Emerging Economies—ASEAN, the People Republic of China, and India—for a Balanced, Resilient and Sustainable Asia. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, the ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. ADBI encourages readers to post their comments on the main page for each working paper (given in the citation below). Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Howes, S. and P. Wyrwoll. 2012. Asia’s Wicked Environmental Problems. ADBI Working Paper 348. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: http://www.adbi.org/working- paper/2012/02/28/5009.asia.wicked.environmental.problems/ Please contact the author(s) for information about this paper. -

SARAWAK GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PART II Published by Authority

For Reference Only T H E SARAWAK GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PART II Published by Authority Vol. LXXI 25th July, 2016 No. 50 Swk. L. N. 204 THE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS ORDINANCE THE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS ORDER, 2016 (Made under section 3) In exercise of the powers conferred upon the Majlis Mesyuarat Kerajaan Negeri by section 3 of the Administrative Areas Ordinance [Cap. 34], the following Order has been made: Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Administrative Areas Order, 2016, and shall be deemed to have come into force on the 1st day of August, 2015. Administrative Areas 2. Sarawak is divided into the divisions, districts and sub-districts specified and described in the Schedule. Revocation 3. The Administrative Areas Order, 2015 [Swk. L.N. 366/2015] is hereby revokedSarawak. Lawnet For Reference Only 26 SCHEDULE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS KUCHING DIVISION (1) Kuching Division Area (Area=4,195 km² approximately) Commencing from a point on the coast approximately midway between Sungai Tambir Hulu and Sungai Tambir Haji Untong; thence bearing approximately 260º 00′ distance approximately 5.45 kilometres; thence bearing approximately 180º 00′ distance approximately 1.1 kilometres to the junction of Sungai Tanju and Loba Tanju; thence in southeasterly direction along Loba Tanju to its estuary with Batang Samarahan; thence upstream along mid Batang Samarahan for a distance approximately 5.0 kilometres; thence bearing approximately 180º 00′ distance approximately 1.8 kilometres to the midstream of Loba Batu Belat; thence in westerly direction along midstream of Loba Batu Belat to the mouth of Loba Gong; thence in southwesterly direction along the midstream of Loba Gong to a point on its confluence with Sungai Bayor; thence along the midstream of Sungai Bayor going downstream to a point at its confluence with Sungai Kuap; thence upstream along mid Sungai Kuap to a point at its confluence with Sungai Semengoh; thence upstream following the mid Sungai Semengoh to a point at the midstream of Sungai Semengoh and between the middle of survey peg nos. -

A Shared Identity

The A SEAN ISSUE 01 | MAY 2020 A Shared Identity Becoming ASEAN ISSN 2721-8058 SHIFTING CURRENTS THE INSIDE VIEW SNAPSHOTS COVID-19: A Collective Unity, Diversity ASEAN Heritage Park Conference Response in ASEAN and ASEAN Identity Highlights Sustainability and Innovation ASEAN CULTURAL HERITAGE Take a Virtual Tour Story on Page 16 Manjusri Sculpture is from a collection of the National Museum of Indonesia. The sculpture carries © Ahttps://heritage.asean.org/ and National Museum of Indonesia great national value for being an iconographic-innovation and the only silver-metal artwork from the Hindu- Buddha period found in the archipelago. Photo Credit: https://heritage.asean.org/ Contents 3 In this issue 22 Secretary-General of ASEAN Dato Lim Jock Hoi Deputy Secretary-General of ASEAN for ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC) Kung Phoak EDITORIAL BOARD Directors of ASCC Directorates Rodora T. Babaran, Ky-Anh Nguyen Assistant Directors of ASCC Divisions Ferdinal Fernando, Jonathan Tan, The Inside View: ASEAN Identity Shifting Currents Mary Anne Therese Manuson, Mega Irena, Ngoc Son Nguyen, Sita Sumrit, Sophearin Chea, Unity, Diversity and the ASEAN Identity 8 Health 30 Vong Sok ASEAN Awareness Poll 10 COVID-19: A Collective Response in ASEAN EDITORIAL TEAM Interview with Indonesian Foreign Minister Editor-in-Chief Opinion: Retno Marsudi 12 Mary Kathleen Quiano-Castro Stop the Prejudice, a Virus Has No Race 36 Fostering ASEAN Identity 14 Associate Editor Fighting Fear and Fake News ASEAN Going Digital 16 Joanne B. Agbisit in a Pandemic 38 -

Module No. 2240 2240-1

Module No. 2240 2240-1 GETTING ACQUAINTED Precautions • Congratulations upon your selection of this CASIO watch. To get the most out The measurement functions built into this watch are not intended for of your purchase, be sure to carefully read this manual and keep it on hand use in taking measurements that require professional or industrial for later reference when necessary. precision. Values produced by this watch should be considered as reasonably accurate representations only. About This Manual • Though a useful navigational tool, a GPS receiver should never be used • Each section of this manual provides basic information you need to perform as a replacement for conventional map and compass techniques. Remember that magnetic compasses can work at temperatures well operations in each mode. Further details and technical information can also be found in the “REFERENCE”. below zero, have no batteries, and are mechanically simple. They are • The term “watch” in this manual refers to the CASIO SATELLITE NAVI easy to operate and understand, and will operate almost anywhere. For Watch (Module No. 2240). these reasons, the magnetic compass should still be your main • The term “Watch Application” in this manual refers to the CASIO navigation tool. • SATELLITE NAVI LINK Software Application. CASIO COMPUTER CO., LTD. assumes no responsibility for any loss, or any claims by third parties that may arise through the use of this watch. Upper display area MODE LIGHT Lower display area MENU On-screen indicators L K • Whenever leaving the AC Adaptor and Interface/Charger Unit SAFETY PRECAUTIONS unattended for long periods, be sure to unplug the AC Adaptor from the wall outlet. -

A Toolkit to Support Conservation by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities

UNEP A toolkit to support conservation by indigenous peoples and local communities: Building capacity and sharing knowledge for Indigenous Peoples’ and Community Conserved Territories and Areas (ICCAs) © 2013 United Nations Environment Programme Produced by United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 0DL United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0) 1223 277 314 UNEP-WCMC is the specialist biodiversity assessment UNDP partners with people at all levels of society to help build centre of the United Nations Environment Programme nations that can withstand crisis, and drive and sustain the (UNEP), the world’s foremost intergovernmental kind of growth that improves the quality of life for everyone. environmental organisation. The Centre has been in On the ground in 177 countries and territories, we offer global operation for over 30 years, combining scientific research perspective and local insight to help empower lives and build with practical policy advice. www.unep-wcmc.org resilient nations. www.undp.org Disclaimers The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP, UNDP or contributory organisations. The designations employed and the presentations of material in this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the parts of UNEP, UNDP or contributory organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory or city or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Reproduction This report may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. -

A Global Overview of Protected Areas on the World Heritage List of Particular Importance for Biodiversity

A GLOBAL OVERVIEW OF PROTECTED AREAS ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST OF PARTICULAR IMPORTANCE FOR BIODIVERSITY A contribution to the Global Theme Study of World Heritage Natural Sites Text and Tables compiled by Gemma Smith and Janina Jakubowska Maps compiled by Ian May UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre Cambridge, UK November 2000 Disclaimer: The contents of this report and associated maps do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP-WCMC or contributory organisations. The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP-WCMC or contributory organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION 1.0 OVERVIEW......................................................................................................................................................1 2.0 ISSUES TO CONSIDER....................................................................................................................................1 3.0 WHAT IS BIODIVERSITY?..............................................................................................................................2 4.0 ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY......................................................................................................................3 5.0 CURRENT WORLD HERITAGE SITES............................................................................................................4 -

LOGISTIC REGRESSION MODEL for PREDICTING MICROBIAL GROWTH and ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE OCCURRENCE in SWIFTLET (Aerodramus Fuciphagus) FAECES

Journal of Sustainability Science and Management eISSN: 2672-7226 Volume 16 Number 4, June 2021: 113-123 © Penerbit UMT LOGISTIC REGRESSION MODEL FOR PREDICTING MICROBIAL GROWTH AND ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE OCCURRENCE IN SWIFTLET (Aerodramus Fuciphagus) FAECES SUI SIEN LEONG*1, SAMUEL LIHAN2, TECK YEE LING3 AND HWA CHUAN CHIA2 1Department of Animal Sciences and Fishery, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Nyabau Road, 97008 Bintulu, Sarawak, Malaysia. 2Institute of Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, 94300 Kota Samarahan, Sarawak, Malaysia. 3Department of Chemistry, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, 94300 Kota Samarahan, Sarawak, Malaysia. *Corresponding author: [email protected] Submitted final draft: 3 March 2020 Accepted: 15 June 2020 http://doi.org/10.46754/jssm.2021.06.010 Abstract: This study proposes a logistic model of the environmental factors which may affect bacterial growth and antibiotic resistance in the swiftlet industry. The highest total mean faecal bacterial (FB) colonies counts (11.86±3.11 log10 cfu/ g) were collected from Kota Samarahan in Sarawak, Malaysia, and the lowest (6.71±1.09 log10 cfu/g) from Sibu in both rainy and dry season from March 2016 till September 2017. FB isolates were highly resistant against penicillin G (42.20±18.35%). Enterobacter and Enterococcal bacteria were resistant to streptomycin (40.00±51.64%) and vancomycin (77.50±41.58%). The model indicated that the bacteria could grow well under conditions of higher faecal acidity (pH 8.27), dry season, higher mean daily temperature (33.83°C) and faecal moisture content (41.24%) of swiftlet houses built in an urban area with significant regression (P<0.0005, N=100). -

An Analysis of Singapore Government's Behavior

วารสารสังคมศาสตร์ มหาวิทยาลัยนเรศวร ปีที่ 13 ฉบับที่ 1 (มกราคม-มิถุนายน 2560) The Return of the Haze: An Analysis of Singapore Government’s Behavior Before and After the 2013 Haze Attack Lee Pei May* and Mohd Shazani bin Masri** *Doctoral Researcher at the School of Politics and International Relations, Univer- sity of Nottingham, UK **Lecturer at Faculty of Social Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak Lee Pei May and Mohd Shazani bin Masri. (2017). 13 (1): 225-235 DOI:10.14456/jssnu.2017.11 Copyright © 2017 by Journal of Social Sciences, Naresuan University: JSSNU All rights reserved Lee Pei May and Mohd Shazani bin Masri Abstract most pertinent issue in Southeast Asia This paper compares and analyses region. This paper does not analyse Singapore government’s commit- how this incidence can induce social ments towards the past haze phenom- movement since haze is a periodical enon with the haze attack on 2013. In phenomenon. Moreover, the nature the past, Singapore seemed to be of this paper does not intend to in- quite willing to tolerate hazy skies and clude policy recommendation to the choking smog caused by the haze; but government because the theoretical the haze in June 2013 oversees signifi- framework employed focus more on cant change in Singapore’s behavior explaining the interactions of differ- from being half-hearted to fully com- ent groups in the society and how it mit in resolving the haze issue. There influences state’s behavior. are many approaches to argue the change in government position, but Keywords: haze, Singapore, Lib- this article argues that the main rea- eralism, behavior, Southeast Asia son behind the change in Singapore’s behavior is due to the persistent com- petition between various individuals and groups. -

5- Informe ASEAN- Centre-1.Pdf

ASEAN at the Centre An ASEAN for All Spotlight on • ASEAN Youth Camp • ASEAN Day 2005 • The ASEAN Charter • Visit ASEAN Pass • ASEAN Heritage Parks Global Partnerships ASEAN Youth Camp hen dancer Anucha Sumaman, 24, set foot in Brunei Darussalam for the 2006 ASEAN Youth Camp (AYC) in January 2006, his total of ASEAN countries visited rose to an impressive seven. But he was an W exception. Many of his fellow camp-mates had only averaged two. For some, like writer Ha Ngoc Anh, 23, and sculptor Su Su Hlaing, 19, the AYC marked their first visit to another ASEAN country. Since 2000, the AYC has given young persons a chance to build friendships and have first hand experiences in another ASEAN country. A project of the ASEAN Committee on Culture and Information, the AYC aims to build a stronger regional identity among ASEAN’s youth, focusing on the arts to raise awareness of Southeast Asia’s history and heritage. So for twelve days in January, fifty young persons came together to learn, discuss and dabble in artistic collaborations. The theme of the 2006 AYC, “ADHESION: Water and the Arts”, was chosen to reflect the role of the sea and waterways in shaping the civilisations and cultures in ASEAN. Learning and bonding continued over visits to places like Kampung Air. Post-camp, most participants wanted ASEAN to provide more opportunities for young people to interact and get to know more about ASEAN and one another. As visual artist Willy Himawan, 23, put it, “there are many talented young people who could not join the camp but have great ideas Youthful Observations on ASEAN to help ASEAN fulfill its aims.” “ASEAN countries cooperate well.” Sharlene Teo, 18, writer With 60 percent of ASEAN’s population under the age of thirty, young people will play a critical role in ASEAN’s community-building efforts. -

Acute Health Impacts of the Southeast Asian Transboundary Haze Problem—A Review

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review Acute Health Impacts of the Southeast Asian Transboundary Haze Problem—A Review Kang Hao Cheong 1,* , Nicholas Jinghao Ngiam 2 , Geoffrey G. Morgan 3, Pin Pin Pek 4,5, Benjamin Yong-Qiang Tan 2, Joel Weijia Lai 1, Jin Ming Koh 1, Marcus Eng Hock Ong 4,5 and Andrew Fu Wah Ho 6,7,8 1 Science and Math Cluster, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore 487372, Singapore 2 Division of Neurology, Department of Medicine, National University Health System, Singapore 119074, Singapore 3 School of Public Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia 4 Department of Emergency Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore 169608, Singapore 5 Health Services & Systems Research, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore 169857, Singapore 6 SingHealth Duke-NUS Emergency Medicine Academic Clinical Programme, Singapore 169857, Singapore 7 National Heart Research Institute Singapore, National Heart Centre, Singapore 169609, Singapore 8 Cardiovascular & Metabolic Disorders Programme, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore 169857, Singapore * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 August 2019; Accepted: 29 August 2019; Published: 6 September 2019 Abstract: Air pollution has emerged as one of the world’s largest environmental health threats, with various studies demonstrating associations between exposure to air pollution and respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. Regional air quality in Southeast Asia has been seasonally affected by the transboundary haze problem, which has often been the result of forest fires from “slash-and-burn” farming methods. In light of growing public health concerns, recent studies have begun to examine the health effects of this seasonal haze problem in Southeast Asia. -

Papua New Guinea Highlands and Mt Wilhelm 1978 Part 1

PAPUA NEW GUINEA HIGHLANDS AND MT WILHELM 1978 PART 1 The predawn forest became alive with the melodic calls of unseen thrushes, and the piercing calls of distant parrots. The skies revealed the warmth of the morning dawn revealing thunderheads over the distant mountains that seemed to reach the melting stars as the night sky disappeared. I was 30 meters above the ground in a tree blind climbed before dawn. Swirling mists enshrouded the steep jungle canopy amidst a great diversity of forest trees. I was waiting for male lesser birds of paradise Paradisaea minor to come in to a tree lek next to the blind, where males compete for prominent perches and defend them from rivals. From these perch’s males display by clapping their wings and shaking their head. At sunrise, two male Lesser Birds-of-Paradise arrived, scuffled for the highest perch and called with a series of loud far-carrying cries that increase in intensity. They then displayed and bobbed their yellow-and-iridescent-green heads for attention, spreading their feathers wide and hopped about madly, singing a one-note tune. The birds then lowered their heads, continuing to display their billowing golden white plumage rising above their rust-red wings. A less dazzling female flew in and moved around between the males critically choosing one, mated, then flew off. I was privileged to have used a researcher study blind and see one of the most unique group of birds in the world endemic to Papua New Guinea and its nearby islands. Lesser bird of paradise lek near Mt Kaindi near Wau Ecology Institute Birds of paradise are in the crow family, with intelligent crow behavior, and with amazingly complex sexual mate behavior.