14-1096 Luna Torres V. Lynch (05/19/2016)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Closed, Vol. 27 Ebook Free Download

CASE CLOSED, VOL. 27 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gosho Aoyama | 184 pages | 29 Oct 2009 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421516790 | English | San Francisco, United States Case Closed, Vol. 27 PDF Book January 20, [22] Ai Haibara. Views Read Edit View history. Until Jimmy can find a cure for his miniature malady, he takes on the pseudonym Conan Edogawa and continues to solve all the cases that come his way. The Junior Detective League and Dr. Retrieved November 13, January 17, [8]. Product Details. They must solve the mystery of the manor before they are all killed off or kill each other. They talk about how Shinichi's absence has been filled with Dr. Chicago 7. April 10, [18] Rachel calls Richard to get involved. Rachel thinks it could be the ghost of the woman's clock tower mechanic who died four years prior. Conan's deductions impress Jodie who looks at him with great interest. Categories : Case Closed chapter lists. And they could have thought Shimizu was proposing a cigarette to Bito. An unknown person steals the police's investigation records relating to Richard Moore, and Conan is worried it could be the Black Organization. The Junior Detectives find the missing boy and reconstruct the diary pages revealing the kidnapping motive and what happened to the kidnapper. The Junior Detectives meet an elderly man who seems to have a lot on his schedule, but is actually planning on committing suicide. Magic Kaito Episodes. Anime News Network. Later, a kid who is known to be an obsessive liar tells the Detective Boys his home has been invaded but is taken away by his parents. -

Case Closed (Surrealistic Horror Story) a Couple of Friends Are Hanging Outside for a Picnic. They Keep Roaming in the Road on A

Case Closed (Surrealistic Horror Story) A couple of friends are hanging outside for a picnic. They keep roaming in the road on a shinny day. They come to find a haunted house and decided to explore it. The house is filled with dust and dirt is almost about to break up. Nevertheless they decided to go in and take a break before proceeding ahead. After exploring the house, friends get hungry and sit down in a room to have lunch. They realized they are out of food and decided to bring some foods while one girl stayed inside as she was getting headache and takes a nap while others go out. She sleeps for many hours (time lapse) and wakes up at night. She noticed no one around in the haunted house and starts to panic and decide to open every door looking for others but ended up going to the same place all the time. Then she tries to take a call for her friends with her smart phone but realize there are no signals in the smart phone. Then she hears an old cartoon laughing sound somewhere in the house and follows that room. She pokes in and shocks seeing a little girl watching a black and white TV. The place implies 70‟s year old vintage environment. The TV, clothes the little girl is wearing, foods all of them were object of 70 year. She gets closer and tries to touch her but realize the girl is unaware of her presence and could not feel as she continues watching the cartoon while laughing miserably. -

Read Book Case Closed: Vol.40 Pdf Free Download

CASE CLOSED: VOL.40 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gosho Aoyama | 184 pages | 10 Nov 2011 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421535005 | English | San Francisco, United States Case Closed: Vol.40 PDF Book Donate Today. Retrieved November 19, Retrieved October 10, Retrieved February 21, Pickup not available. Please Save My Earth. I agree to the Terms and Conditions. Viz Media. This new model will increase opportunities for the community to contribute to ;login: and engage with its content. Gosho Aoyama. By Gosho Aoyama. But to find her, they'll have to crack a numerical code that takes them on a wild goose chase through the local zoo! Magic Kaito Episodes. December 25, []. We aim to show you accurate product information. Chingwin Publishing Group. December 24, []. Related Searches. Rik Farrow, the current editor of the magazine, will continue to provide leadership for the overall content offered in ;login: , which will be released via our website on a regular basis throughout the year. Retrieved October 20, You may block cookies via standard web-browser settings, but this site may not function correctly without cookies. August 18, []. Episode list 1 Season 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Episode list 2 Season 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 OVAs Lupin the 3rd vs. Recent searches Clear All. You have been sent an email with instructions on how to reset your password. Book Depository. December 10, [42] Egmont licensed series in Sweden , Norway , Finland and Denmark , but dropped them either because low sales Sweden , [16] unknown reason Denmark and Norway [17] [18] or when Egmont closed its manga-publishing division in Finland. -

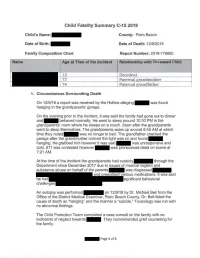

Child Fatality Summary C-15 2018

Child Fatality Summary C-15 2018 Child's Name: County: Palm Beach Date of Birth: - Date of Death: 12/9/2018 Family Composition Chart Report Number: 2018-776880 Name Relationship with Deceased Child 1. Circumstances Surrounding Death On 12/9/18 a report was received by the Hotline alleging - was found hanging in the grandparents' garage. On the evening prior to the incident, it was said the family had gone out to dinner and - behaved normally. He went to sleep around 10:30 PM in the grandparents' room where he sleeps on a couch. Soon after the grandparents went to sleep themselves. The grandparents woke up around 6:45AM at which time they noted - was no longer in bed. The grandfather checked the garage after the grandmother noticed the light was on and found hanging. He grabbed him however it was said - was unresponsive and cold. 911 was contacted however- was pronounced dead on scene at 7:21AM. At the time of the incident the grandparents had custody- through the Department since December 2017 due to issues of medical neglect and substance abuse on behalf of the pa was diagnosed - s medications. It was said .,,,.,,.. ,,.,,.,"",.,.,. behavioral An autopsy was performed on 12/9/18 by Dr. Michael Bell from the Office of the District Medica , Palm Beach County. Dr. Bell listed the cause of death as "hanging" and the manner a "suicide." Toxicology was run with no abnormal findings. The Child Protection Team completed a case consult on the family with no indicators of neglect towards- - They recommended grief counseling for the family. -

Portrayals of Police and Crime in Japanese Anime and Manga

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository ALL THE EVIL OF GOOD: PORTRAYALS OF POLICE AND CRIME IN JAPANESE ANIME AND MANGA By Katelyn Mitchell Honors Thesis Department of Asian Studies University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill April 23, 2015 Approved: INGER BRODEY (Student’s Advisor) 1 “All the Evil of Good”: Portrayals of Police and Crime in Japanese Anime and Manga By Katelyn Mitchell “Probity, sincerity, candor, conviction, the idea of duty, are things that, when in error, can turn hideous, but – even though hideous, remain great; their majesty, peculiar to the human conscience, persists in horror…Nothing could be more poignant and terrible than [Javert’s] face, which revealed what might be called all the evil of good” -Victor Hugo, Les Misérables Volume I, Book VIII, Chapter III: “Javert Satisfied” Abstract This thesis examines and categorizes the distinct, primarily negative, portrayals of law enforcement in Japanese literature and media, beginning with its roots in kabuki drama, courtroom narratives and samurai codes and tracing it through modern anime and manga. Portrayals of police characters are divided into three distinct categories: incompetents used as a source of comedy; bland and consistently unsuccessful nemeses to charismatic criminals, used to encourage the audience to support and favor these criminals; or cold antagonists fanatically devoted to their personal definition of ‘justice’, who cause audiences to question the system that created them. This paper also examines Western influences, such as Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes and Victor Hugo’s Inspector Javert, on these modern media portrayals. -

Case Management Examples Page - 1

FSML - 55 CM-WG #1 10/01/09 Case Management Examples Page - 1 WORKER GUIDE Case Management Examples 1. Generic Case Management Case management consists of these elements. (Eligibility items are italicized.) Screening and Assessment to obtain basic information for case management and eligibility purposes. This includes the following steps: • Reviewing the application. • Reviewing the My Self Assessment (DHS 7823) form with the client. • Reviewing prior case history (case file, TRACS). • Reviewing the testing screen on TRACS for results of any screenings or assessments the client has completed. • Checking the appropriate screens. Possible Questions or Statements to gather information about client circumstances. • Tell me about any recent job losses you may have experienced. • Tell me about your work history and educational background. • Who lives in the home; who is working; who is in school; who is a citizen? How would these individuals support you or be a barrier to your participation in activities? • How old are the individuals in your home, and what is your relationship with them? • Who is not in the home, but who is involved with the family, and what resources do they offer? • What income is available to you? • Are there personal resources such as transportation, child care that you can use? • Tell me about any health problems you or members of your family may be experiencing. Are they affecting the family functioning (physical, mental, intellectual functioning)? • Are alcohol & drug (A&D) issues affecting the family? If yes, how are they affecting the family? CM-WG #1 FSML - 55 Page - 2 Case Management Examples 10/01/09 • Are there concerns about safety for any member of the family? Tell me about that. -

Case Closed: V. 15 PDF Book

CASE CLOSED: V. 15 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gosho Aoyama | 208 pages | 06 Oct 2008 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421504452 | English | San Francisco, United States Case Closed: v. 15 PDF Book By the short trip close to the stage, Conan got some clues to resolve the case. SeHa Girls Cardfight!! Manda, a well-known author, is greeted by his editor who needs his manuscript. This charade is an embarrassment to the country. Haibara warns Conan not to show off because he'll attract attention, so he tries to guide Takagi and Megure to the clues in his usual childish manner. They learn that Mikami that Osamu is not answering his phone calls and he was going to check up on him. Each of the two debaters should be given an uninterrupted 30 or 45 minutes to discuss things they deem important, not the subjects selected by the moderators. We use cookies to provide our services , for example, to keep track of items stored in your shopping basket, prevent fraudulent activity, improve the security of our services, keep track of your specific preferences e. Day after agonising day, the Fukushima Daiichi power plant was an island, plunged into darkness, without electricity or emergency diesel generators, and almost completely devoid of resources. Languages English. Conan also tries to gather clues to help, but is limited to what he can do when a sneaky Eisuke starts to spy and watch him. He lauded the commitment of his colleagues inside the plant, even as he deplored the absence or incompetence of those outside — Tepco headquarters, the government, the regulatory authority, and so on. -

Sherlock Holmes Films

Checklist of Sherlock Holmes (and Holmes related) Films and Television Programs CATEGORY Sherlock Holmes has been a popular character from the earliest days of motion pictures. Writers and producers realized Canonical story (Based on one of the original 56 s that use of a deerstalker and magnifying lens was an easily recognized indication of a detective character. This has led to stories or 4 novels) many presentations of a comedic detective with Sherlockian mannerisms or props. Many writers have also had an Pastiche (Serious storyline but not canonical) p established character in a series use Holmes’s icons (the deerstalker and lens) in order to convey the fact that they are acting like a detective. Derivative (Based on someone from the original d Added since 1-25-2016 tales or a descendant) The listing has been split into subcategories to indicate the various cinema and television presentations of Holmes either Associated (Someone imitating Holmes or a a in straightforward stories or pastiches; as portrayals of someone with Holmes-like characteristics; or as parody or noncanonical character who has Holmes's comedic depictions. Almost all of the animation presentations are parodies or of characters with Holmes-like mannerisms during the episode) mannerisms and so that section has not been split into different subcategories. For further information see "Notes" at the Comedy/parody c end of the list. Not classified - Title Date Country Holmes Watson Production Co. Alternate titles and Notes Source(s) Page Movie Films - Serious Portrayals (Canonical and Pastiches) The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes 1905 * USA Gilbert M. Anderson ? --- The Vitagraph Co. -

List of Case Closed Episodes (Season 1)

List of Case Closed episodes (season 1) Ep no. Funimation dub title/Original translated Original English Jp En title Orig. Funi. airdate airdate . g. Original Japanese title "The Big Shrink" / "Roller Coaster Murder Case" January 8, May 24, 01 01 "Jet Coaster Satsujin Jiken" (ジェットコースター 1996 2004[21] 殺人事件) A man is murdered during a party and the detective Jimmy Kudo is called to solve the case. He reveals that the host is the murderer and solves the case. Jimmy and his friend, Rachel Moore then take a trip to an amusement park. While they are there a man is decapitated during a roller coaster ride. Jimmy reveals the murderer to be the man's ex-girlfriend, Haley. He shows that Haley used her necklace made of piano wire and a hook in her purse, looped the wire around the victim's neck and hooked the wire onto the roller coaster tracks during the ride. Haley explains that the victim broke up with her and she had planned a murder suicide. After solving this case Jimmy follows two suspicious men in black from the roller coaster case and watches them make a clandestine deal. Jimmy is attacked from behind by the two men and forced to take a newly developed poison that should kill him. "The Kidnapped Debutante" / "Company January May 25, 02 02 President's Daughter Kidnapping Case" 15, 1996 2004[21] "Shachō Reijō Yūkai Jiken" (社長令嬢誘拐事件) Jimmy wakes up and finds that he is now in the body of a young child as a result of the poison. -

CIA Letter Says

UNCLASSIFIED//FOUO Central Intelligence Agency Washington. D. C2050S 23 February 2005 Mr. Howard P. Lowell Director, Modern Records Programs National Archives and Records Administration 8601 Adelphi Road CnJ lege Park, MD 20740--6001 Dear Mr. Lowell: (U) In your letter of 23 November 2004, you asked that we examine our record holdings to determine the disposition of "classified annexes to the Intelligence Authorization Acts for FYs 1947 through 1970." (U) In response to your request, our records managers completed extensive research into the development of annexes and related budget documents and for verification of their findings also completed an exhaustive hand search of budget data of the Office of the Comptroller, the Office of Congressional Affairs and predecessor organizations, for fiscal years 1947 through 1970. (0//F8UO) We determined that the "classified annexes" are documents produced in Congress that specifically define how ·funding appropriated for the Central Intelligence Agency budget shall be spent. The Intelligence Authorization Act that precipitated these documents was first enacted in 1979 and these external documents were not produced until the early 1980's. Hence, the documents are not extant for the fiscal years 1947 through 1970 and no evidence exists that would require a report under 36 CFR 1228.104. (U//F8UO) It is our understanding that prior to 1979 CIA budget figures were disclosed to CIA from closely held informal Congressional documentation maintained by Congress and not formally disseminated to the Agency. Unfortunately, this Congressional documentation was anachronistically referred to in the Stockman declaration as "classified annexes" to "intelligence authorization acts." UNCLASSIFIED//P999 UNCLASSIFIED//~eee· Mr. -

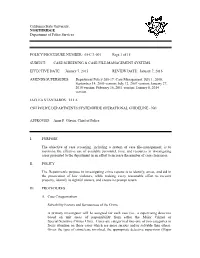

05-C.I.-001 Page 1 of 15

California State University, NORTHRIDGE Department of Police Services POLICY/PROCEDURE NUMBER: 05-C.I.-001 Page 1 of 15 SUBJECT: CASE SCREENING & CASE FILE-MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS EFFECTIVE DATE: January 7, 2015 REVIEW DATE: January 7, 2016 AMENDS/SUPERSEDES: Department Policy 200-17: Case Management, July 1, 2000; September 14, 2005 version; July 12, 2007 version; January 27, 2010 version; February 16, 2011 version; January 8, 2014 version. IACLEA STANDARDS: 13.1.6 CSU POLICE DEPARTMENTS SYSTEMWIDE OPERATIONAL GUIDELINE - NO APPROVED: Anne P. Glavin, Chief of Police I. PURPOSE The objective of case screening, including a system of case file-management, is to maximize the effective use of available personnel, time, and resources in investigating cases presented to the department in an effort to increase the number of case clearances. II. POLICY The Department's purpose in investigating crime reports is to identify, arrest, and aid in the prosecution of law violators, while making every reasonable effort to recover property, identify its rightful owners, and ensure its prompt return. III. PROCEDURES A. Case Categorization Solvability Factors and Seriousness of the Crime A primary investigator will be assigned for each case (i.e., a supervising detective based on unit areas of responsibility from either the Major Crimes or Special/Sensitive Crimes Unit). Cases are categorized into one of two categories to focus attention on those cases which are more serious and/or solvable than others. Given the type of crime/case involved, the appropriate detective supervisor (Major 2 Crimes or Special/Sensitive Crimes Unit) will assign and supervise those cases eligible for follow-up investigation to an individual investigator or field/patrol officer based on specialized skills, knowledge, or abilities that may be required to complete a thorough investigation. -

Portrayals of Police and Crime in Japanese Anime and Manga

ALL THE EVIL OF GOOD: PORTRAYALS OF POLICE AND CRIME IN JAPANESE ANIME AND MANGA By Katelyn Mitchell Honors Thesis Department of Asian Studies University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill April 23, 2015 Approved: INGER BRODEY (Student’s Advisor) 1 “All the Evil of Good”: Portrayals of Police and Crime in Japanese Anime and Manga By Katelyn Mitchell “Probity, sincerity, candor, conviction, the idea of duty, are things that, when in error, can turn hideous, but – even though hideous, remain great; their majesty, peculiar to the human conscience, persists in horror…Nothing could be more poignant and terrible than [Javert’s] face, which revealed what might be called all the evil of good” -Victor Hugo, Les Misérables Volume I, Book VIII, Chapter III: “Javert Satisfied” Abstract This thesis examines and categorizes the distinct, primarily negative, portrayals of law enforcement in Japanese literature and media, beginning with its roots in kabuki drama, courtroom narratives and samurai codes and tracing it through modern anime and manga. Portrayals of police characters are divided into three distinct categories: incompetents used as a source of comedy; bland and consistently unsuccessful nemeses to charismatic criminals, used to encourage the audience to support and favor these criminals; or cold antagonists fanatically devoted to their personal definition of ‘justice’, who cause audiences to question the system that created them. This paper also examines Western influences, such as Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes and Victor Hugo’s Inspector Javert, on these modern media portrayals. It also examines the contradictions between these negative, antagonistic characters and existing facts and statistics – Japan’s low crime rate and generally high reports of civilian satisfaction with the police.