Addiction and Expression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nofap Timeline: What to Expect and When to Expect It

NoFap Timeline: What to expect and when to expect it Note: This is a generalized guide, you may experience these effects at slightly different times to those listed here, but most people can expect to follow this progression down to the week. Week 1 • 2rges to watch porn signi3cantly decrease from this point. • You will think about porn 24/7. • This is the most difficult week, by far. • %/rain #og” "hould be noticeably reduced, with decreases in daydreaming, spacing out during Day 2 ! con&ersations, muddling of words, fatigue, lack of concentration, and forgetfulness. • You are most likely to #ail. • You will be noticeably le"" "tre""ed. • Insane urges to fap. orn will be on your mind • Noticeably impro+ed confidence. !"#$. • 4onsiderably more ener&y* • (ou will be more producti+e and moti+ated. Day 4 $ • It)s likely that you will %#eel like a new man' by this point, though that may occur during week • Your %#og&y brain' will begin to #ade from this two. point, but you will not see ma%or impro&ements until week '. • You will feel a good sense of achie&ement after 1 2 months not fapping for ' days, but "tay di"ciplined. • 0ost notable "pike of impro+ement in psyche and &eneral health. Day 7 • You may notice things like an increa"e in mu"cle ma"", e&en if you aren)t working out. /Though, • Testosterone is peaking. you should be working out during nofap, as it • (trong urges to fap, again don)t get complacent. boosts testosterone and helps spend pent-up • *owe&er, ur&e" begin to decrea"e #rom thi" energy0. -

Sex Addiction in the Digital Age

ALWAYS TURNED ON SEX ADDICTION IN THE DIGITAL AGE ROBERT WEISS, LCSW, CSAT-S JENNIFER SCHNEIDER, MD, PHD Gentle Path Press P.O. Box 3172 Carefree, Arizona 85377 gentlepath.com Copyright © 2015 by Gentle Path Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced, stored or entered into a retrieval system, transmitted, photocopied, recorded, or otherwise reproduced in any form by any mechanical or electronic means, without the prior written permission of the author, and Gentle Path Press, except for brief quotations used in articles and reviews. First edition: 2015 For more information regarding our publications, please contact Gentle Path Press at 1-800-708-1796 (toll-free U.S. only) ISBN: 978-1-9404670-1-6 Converted by http://www.eBookIt.com Editor’s note: All the stories in this book are based on actual experiences. The names and details have been changed to protect the privacy of people involved. In some cases, composites have been created. Any resemblance to actual persons is entirely coincidental. ADVANCE PRAISE Authors Weiss and Schneider capture the essence of how rapidly technology is changing arousal and attachment patterns and what you can do about it. This is sure to become the book that both clinicians and lay readers turn to in order to sort out the complexities of how technology turns us on. —Dr. Kenneth M. Adams, author of Silently Seduced: When Parents Make Their Children Partners and When He’s Married to Mom: How to Help Mother Enmeshed Men Open Their Hearts to True Love and Commitment and co-editor of Clinical Management of Sex Addiction Always Turned On is packed with the most up-to-date information about sex addiction in the digital age. -

Syllabus 2021

History 201: The History of Now Professor Patrick Iber Spring 2021 / TuTh 9:30-10:45AM / online Office Hours: Wednesday 11am-1pm, online [email protected] (608) 298-8758 TA: Meghan O’Donnell, [email protected] Sections: W 2:25-3:15; W 3:30-4:20; W 4:35-5:25 This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA History is the study of change over time, and requires hindsight to generate insight. Most history courses stop short of the present, and historians are frequently wary of applying historical analysis to our own times, before we have access to private sources and before we have the critical distance that helps us see what matters and what is ephemeral. But recent years have given many people the sense of living through historic times, and clamoring for historical context that will help them to understand the momentous changes in politics, society and culture that they observe around them. This experimental course seeks to explore the last twenty years or so from a historical point of view, using the historian’s craft to gain perspective on the present. The course will consider major developments—primarily but not exclusively in U.S. history—of the last twenty years, including 9/11 and the War on Terror, the financial crisis of 2008 and its aftermath, social movements from the Tea Party to the Movement for Black Lives, and political, cultural, and the technological changes that have been created by and shaped by these events. This course is designed to be an introduction to historical reasoning, analysis, writing, and research. -

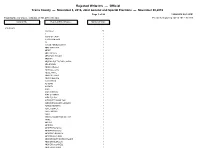

Rejected Write-Ins

Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 1 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT <no name> 58 A 2 A BAG OF CRAP 1 A GIANT METEOR 1 AA 1 AARON ABRIEL MORRIS 1 ABBY MANICCIA 1 ABDEF 1 ABE LINCOLN 3 ABRAHAM LINCOLN 3 ABSTAIN 3 ABSTAIN DUE TO BAD CANDIA 1 ADA BROWN 1 ADAM CAROLLA 2 ADAM LEE CATE 1 ADELE WHITE 1 ADOLPH HITLER 2 ADRIAN BELTRE 1 AJANI WHITE 1 AL GORE 1 AL SMITH 1 ALAN 1 ALAN CARSON 1 ALEX OLIVARES 1 ALEX PULIDO 1 ALEXANDER HAMILTON 1 ALEXANDRA BLAKE GILMOUR 1 ALFRED NEWMAN 1 ALICE COOPER 1 ALICE IWINSKI 1 ALIEN 1 AMERICA DESERVES BETTER 1 AMINE 1 AMY IVY 1 ANDREW 1 ANDREW BASAIGO 1 ANDREW BASIAGO 1 ANDREW D BASIAGO 1 ANDREW JACKSON 1 ANDREW MARTIN ERIK BROOKS 1 ANDREW MCMULLIN 1 ANDREW OCONNELL 1 ANDREW W HAMPF 1 Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 2 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT Continued.. ANN WU 1 ANNA 1 ANNEMARIE 1 ANONOMOUS 1 ANONYMAS 1 ANONYMOS 1 ANONYMOUS 1 ANTHONY AMATO 1 ANTONIO FIERROS 1 ANYONE ELSE 7 ARI SHAFFIR 1 ARNOLD WEISS 1 ASHLEY MCNEILL 2 ASIKILIZAYE 1 AUSTIN PETERSEN 1 AUSTIN PETERSON 1 AZIZI WESTMILLER 1 B SANDERS 2 BABA BOOEY 1 BARACK OBAMA 5 BARAK -

In the Supreme Court of the United States

No. XX-XX In the Supreme Court of the United States KATHLEEN SEBELIUS, SECRETARY OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, ET AL., PETITIONERS v. HOBBY LOBBY STORES, INC., ET AL. ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI DONALD B. VERRILLI, JR. Solicitor General Counsel of Record STUART F. DELERY Assistant Attorney General EDWIN S. KNEEDLER Deputy Solicitor General JOSEPH R. PALMORE Assistant to the Solicitor General MARK B. STERN ALISA B. KLEIN Attorneys Department of Justice Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 [email protected] (202) 514-2217 QUESTION PRESENTED The Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (RFRA), 42 U.S.C. 2000bb et seq., provides that the government “shall not substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion” unless that burden is the least restrictive means to further a compelling governmen- tal interest. 42 U.S.C. 2000bb-1(a) and (b). The ques- tion presented is whether RFRA allows a for-profit corporation to deny its employees the health coverage of contraceptives to which the employees are other- wise entitled by federal law, based on the religious objections of the corporation’s owners. (I) PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDINGS Petitioners are Kathleen Sebelius, Secretary of Health and Human Services; the Department of Health and Human Services; Thomas E. Perez, Secre- tary of Labor; the Department of Labor; Jacob J. Lew, Secretary of the Treasury; and the Department of the Treasury. Respondents are Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc.; Mardel, Inc.; David Green; Barbara Green; Mart Green; Steve Green; and Darsee Lett. -

Mass Effect 2 Unofficial Guide

SuperCheats.com Unoffical Mass Effect 2 Guide http://www.supercheats.com/guides/mass-effect-2 Check back for updates, videos and comments for this guide. Table of Contents Introduction 2 Character Creation 3 Hacking 5 Getting Started 6 Normandy Prologue 7 Intro 8 Freedom's Progress 15 The Normandy SR2 19 Omega 23 - Recruit the Veteran 24 (DLC Character) - Recruit Archangel 25 - Recruit Professor 35 Mordin Solus Omega Side Quests 43 Recruit The Convict 48 Recruit The rogan 52 Save Horizon 59 Illium 68 Illium Side-Quests 79 Recruit Tali 84 The Collector Ship 91 Loyalty Missions 94 - Miranda: The Prodigal 95 - Jacob: The Gift of Greatness 99 - Jack: Subject Zero 102 - Garrus: Eye for an Eye 105 - Mordin: Old Blood 108 - Grunt: Rite of Passage 113 - Thane: Sins of the Father 117 Samara: The Ardat-Yakshi 119 - Tali: Treason 121 - Zaeed: The Price of Revenge 123 page pnb / nb SuperCheats.com Unoffical Mass Effect 2 Guide http://www.supercheats.com/guides/mass-effect-2 Check back for updates, videos and comments for this guide. Reaper IFF 128 Recruitment: Legion 133 Legion: A House Divided 134 IFF Installation 138 Suicide Mission 139 Normandy Assignments 151 Downloadable Content 169 DLC: Normandy Crash Site 170 DLC: Firewalker MSV Rosalie 172 DLC: Firewalker: Recover Research Data 173 DLC: Firewalker: Artifact Collection 175 DLC: Firewalker: Geth Incursion 177 DLC: Firewalker: Prothean Site 178 DLC: asumi Goto 179 - asumi: Stealing Memory 181 The Citadel 185 Tuchanka 187 Romance 190 Planetary Mining 192 Xbox 360 Achievements 196 page 2 / 201 SuperCheats.com Unoffical Mass Effect 2 Guide http://www.supercheats.com/guides/mass-effect-2 Check back for updates, videos and comments for this guide. -

How Disney's Abc Avoided Reporting Electronic Arts Star Wars Game Micro

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Major Papers Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 2018 HOW DISNEY’S ABC AVOIDED REPORTING ELECTRONIC ARTS STAR WARS GAME MICRO-TRANSACTIONS Rohan Khanna University of Windsor, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/major-papers Part of the Communication Commons, and the Models and Methods Commons Recommended Citation Khanna, Rohan, "HOW DISNEY’S ABC AVOIDED REPORTING ELECTRONIC ARTS STAR WARS GAME MICRO- TRANSACTIONS" (2018). Major Papers. 41. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/major-papers/41 This Major Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in Major Papers by an authorized administrator of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW DISNEY’S ABC AVOIDED REPORTING ELECTRONIC ARTS STAR WARS GAME MICRO-TRANSACTIONS by Rohan Khanna A Major Research Paper Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through Communication and Social Justice in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2018 © 2018 Rohan Khanna HOW DISNEY’S ABC AVOIDED REPORTING ELECTRONIC ARTS STAR WARS GAME MICRO-TRANSACTIONS by Rohan Khanna APPROVED BY: ———————————————— V. Manzerolle Communication, Media, and Film ———————————————— J. P. Winter, Advisor Communication, Media, and Film May 10, 2018 iii AUTHOR’S DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I hereby certify that I am the sole author of this MRP and that no part of this Major paper has been published or submitted for publication. -

UPDATE GAM Far Cry 3 V.1 Frozen Hear Dark Shadow Manhunter

UPDATE GAME Far Cry 3 V.1.01 - RELOADED = 3DVD AUTORUN Frozen Hearth = 1DVD Dark Shadows Army of Evil = 1DVD Manhunter = 1DVD Hitman Absolution - SKIDROW ( NO STEAM ) = 3DVD AUTORUN Empire Earth 3 = 2 LEGO Harry Potter Years 1-4 (2010) = 2 LEGO Lord of the Rings = 2DVD AUTORUN Scribblenauts Unlimited = 1DVD Family Guy Back to the Multiverse = 1DVD Premier Manager 2013 = 1DVD Sonic Adventure 2 = 1DVD Space Colony HD = 1DVD Doctor Who The Eternity Clock = 1DVD FIFA Manager 13 - PREMIUM PACK EDITION V.1.0.1.0 = 2DVD AUTORUN Agricultural Simulator 2013 = 1DVD Borderlands 2 Complete Edition V.1.2.2 ( NO STEAM ) = 3DVD AUTORUN Haunted = 1DVD Real Heroes Fire Fighter = 1DVD Iron Sky Invasion V.1.1 = 1DVD The Lost Chronicles of Zerzura = 1DVD Assassins Creed 3 V.1.01 - OFFLINE = 4DVD AUTORUN GAK PAKE LOGIN2 UPLAY Stained = 1DVD Fly’N = 1DVD F1 Race Stars = 1DVD Louisiana Adventure = 1DVD NOX = 1DVD Panzer Corps Afrika Korps = 1DVD The Sims 3 Seasons - RELOADED = 1DVD Call Of Duty Black Ops 2 - SKIDROW ( NO STEAM ) = 4DVD AUTORUN Stronghold HD = 1DVD Stronghold Crusader HD = 1DVD Into the Dark = 1DVD Red Johnsons Chronicles = 1DVD Sine Mora = 1DVD Rocketbirds Hardboiled Chicken = 1DVD Edna and Harvey Harveys New Eyes = 1DVD Emergency 2013 = 2DVD XCOM: Enemy Unknown = 3DVD Zoo Tycoon 2 = 1DVD 007 Legends FIX SOUND = 2DVD AUTORUN Painkiller Hell and Damnation = 1DVD Cognition Episode 1 The Hangman = 1DVD Chaos on Deponia = 1DVD Medal of Honor Warfighter V.1.0.0.2 = 4DVD AUTORUN Dishonored = 2DVD AUTORUN Need for Speed Most Wanted 2012 = 2DVD AUTORUN -

Merchants Of

Introduction The Jews never faced much anti-Semitism in America. This is due, in large part, to the underlying ideologies it was founded on; namely, universalistic interpretations of Christianity and Enlightenment ideals of freedom, equality and opportunity for all. These principles, which were arguably created with noble intent – and based on the values inherent in a society of European-descended peoples of high moral character – crippled the defenses of the individualistic-minded White natives and gave the Jews free reign to consolidate power at a rather alarming rate, virtually unchecked. The Jews began emigrating to the United States in waves around 1880, when their population was only about 250,000. Within a decade that number was nearly double, and by the 1930s it had shot to 3 to 4 million. Many of these immigrants – if not most – were Eastern European Jews of the nastiest sort, and they immediately became vastly overrepresented among criminals and subversives. A 1908 police commissioner report shows that while the Jews made up only a quarter of the population of New York City at that time, they were responsible for 50% of its crime. Land of the free. One of their more common criminal activities has always been the sale and promotion of pornography and smut. Two quotes should suffice in backing up this assertion, one from an anti-Semite, and one from a Jew. Firstly, an early opponent of the Jews in America, Greek scholar T.T. Timayenis, wrote in his 1888 book The Original Mr. Jacobs that nearly “all obscene publications are the work of the Jews,” and that the historian of the future who shall attempt to describe the catalogue of the filthy publications issued by the Jews during the last ten years will scarcely believe the evidence of his own eyes. -

Reward: +3.1 Objective: Find Optimal Action in Each State to Maximize the Sum of Rewards

Smart Bots for Better Games: Reinforcement Learning in Production Olivier Delalleau Data Scientist @ Ubisoft La Forge Objective Share practical lessons from using RL-based bots in video game production Agenda 1. RL & games 2. Learning from pixels 3. Learning from game state 4. Learning from simulation 5. Epilogue 1.Reinforcement learning & games 2.Learning from pixels 3.Learning from game state 4.Learning from simulation 5.Epilogue [image source] [image sources: #1 #2 #3 #4 #5] Potential application #1: player-facing AI Blade & Soul (2016) Starcraft II (AlphaStar, 2019) Black & White (2001) Dota 2 [image sources: #1 #2 #3 #4] (OpenAI Five, 2018) Potential application #2: testing assistant Open World (Far Cry: New Dawn, 2019) Live multiplayer (Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six Siege, 2015-…) [image sources: #1 #2] In this talk: prototypes @Ubisoft Goal: player-facing AI Goal: testing assistant What is reinforcement learning? state: enemy_visible=1 enemy_aimed=1 What is reinforcement learning? new state: enemy_visible=0 enemy_aimed=0 reward: +3.1 Objective: Find optimal action in each state to maximize the sum of rewards Q-values: Q(state, action) = sum of future rewards when taking an action in a given state action: ”fire” Taking the optimal action = taking the action with maximum Q-value Search/Planning vs RL Offline + … Runtime Q(푠0, 푎0) = 0.8 … Q(푠0, 푎1) = 0.7 [scientist icon by Vincent Le Moign] In a nutshell: why reinforcement learning? Automated AI generation from reward alone “If you can play, you can learn” It’s not magic (…) [icons from pngimg.com] 1.Reinforcement learning & games 2.Learning from pixels 3.Learning from game state 4.Learning from simulation 5.Epilogue [image source] Deep Q-Network (DQN) in action Human-level control through Deep Reinforcement Learning (Mnih et al. -

How Do Loot Boxes Make Money? an Analysis of a Very Large Dataset of Real Chinese CSGO Loot Box Openings

How do loot boxes make money? An analysis of a very large dataset of real Chinese CSGO loot box openings David Zendle, University of York* Elena Petrovskaya, University of York Heather Wardle, University of Glasgow *corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Loot boxes are a form of video game monetisation that shares formal similarities with gambling. There are concerns that loot box revenues are disproportionately drawn from a small percentage of heavily-involved individuals, as is the case with gambling, leading to the potential for financial harm. In this paper we analyse a dataset of 1,469,913 loot box purchases from 386,269 separate Chinese users of the game Counter-Strike: Global Offensive. The Gini coefficient was used to measure the distribution of spending, and how much spending was concentrated within top percentiles. It estimated the concentration of spending amongst loot box openers as lower than observed elsewhere amongst gamblers (95CI: 63.76% - 64.26%). However, the majority of loot box revenue is drawn from the top 10% of players, with 1% alone responsible for 26.33% of all revenue. Overall, this research provides a crucial first step in understanding the financial consequences of loot box monetisation. Introduction Loot boxes are items in video games that may be purchased for real-world money, but which contains randomised contents of uncertain value. Loot boxes are extraordinarily widespread in video games: The majority of top-grossing mobile games contain loot boxes, and the majority of play sessions on desktop take place in a game that features loot boxes1,2. -

Exploring Motivations for Virtual Rewards in Online F2P Gacha Games: Considering

Exploring motivations for virtual rewards in online F2P Gacha games: Considering income level, consumption habits and game settings In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Bachelor of Science in Global Business by DONG Yulai 1025594 May, 2020 ABSTRACT The objective of this study is to figure out players’ motivation on paying for virtual rewards in online F2P Gacha games. Based on the previous studies and primary survey, this paper will draw a conclusion with a primary survey collection which covered more than 3700 adept Gacha game players. Possible factors including income level, consuming habits and game settings which may be players’ paying motivations are analyzed to weigh their dependency about how they sustain and influence players’ playing and consuming behaviors. The correlation analysis and regression analysis will be used to measure the relationship between these factors and payment for Gacha games. As a result, players’ income level has a significant correlation with their payment in Gacha games while their consuming habits in other virtual goods doesn’t have a significant positive correlation with paying for Gacha games. Keywords: F2P Gacha game; virtual goods; consumer behavior; online payment INTRODUCTION Gacha game is generated from Gashapon, a kind of capsule toy derived from Japanese Bandai company that consumers can get a random one from a sets of given toys in a loot box (Toto, 2012). The system of Gashapon and loot box are applied to the initially Free-to-Play on- line game no matter PC games or mobile games since 2010s. However, the loot box system in these so-called “free-to-play” game lures players to spend a lot on in-game virtual currency for the possibility of getting random virtual rewards such as rare items or game characters (Nieborg, 2016).