In This Paper I Develop a Compositional Account of Binding out of DP (BOOD; Sometimes Called Indirect Binding) Which Uses E-Type Pronouns and Situation Semantics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Semantics in Generative Grammar. by Irene Heim & Angelika Kratzer

Semantics in generative grammar. By Irene Heim & Angelika Kratzer. Malden & Oxford: Blackwell, 1998. Pp. ix, 324. Introduction to natural language semantics. By Henriëtte de Swart. Stanford: CSLI Publications, 1998. Pp. xiv, 257. Although there aren’t that many text books on formal semantics, their average quality is quite good, and these two recent additions don’t lower the standard by any means. ‘Semantics in generative grammar’ (SGG) is the more innovative of the two. As its title indicates, SGG focuses its attention on the syntax/semantics interface, with particular emphasis on quantification and anaphora. These two subjects are discussed in considerable detail, while many others receive only a cursory treatment or are not addressed at all. We learn from the preface that this was a deliberate choice: ‘We want to help students develop the ability for semantic analysis, and, in view of this goal, we think that exploring a few topics in detail is more effective than offering a bird’s-eye view of everything.’ (p. ix) Having enjoyed the results of Heim and Kratzer’s explorations, I can only agree with this judgment. SGG falls into three main parts. The first part introduces the two notions that are at the heart of the formal semantics enterprise, viz. truth conditions and compositionality, and then goes on to develop a compositional truth- conditional semantics for a core fragment of English. The second part discusses variable binding and quantification, and the third part is an in-depth discussion of anaphora. All these developments are kept within an extensional framework. 06-09-1999 1 Intensional phenomena are addressed only briefly, in the last chapter of the book. -

Semantics and Pragmatics

Semantics and Pragmatics Christopher Gauker Semantics deals with the literal meaning of sentences. Pragmatics deals with what speakers mean by their utterances of sentences over and above what those sentences literally mean. However, it is not always clear where to draw the line. Natural languages contain many expressions that may be thought of both as contributing to literal meaning and as devices by which speakers signal what they mean. After characterizing the aims of semantics and pragmatics, this chapter will set out the issues concerning such devices and will propose a way of dividing the labor between semantics and pragmatics. Disagreements about the purview of semantics and pragmatics often concern expressions of which we may say that their interpretation somehow depends on the context in which they are used. Thus: • The interpretation of a sentence containing a demonstrative, as in “This is nice”, depends on a contextually-determined reference of the demonstrative. • The interpretation of a quantified sentence, such as “Everyone is present”, depends on a contextually-determined domain of discourse. • The interpretation of a sentence containing a gradable adjective, as in “Dumbo is small”, depends on a contextually-determined standard (Kennedy 2007). • The interpretation of a sentence containing an incomplete predicate, as in “Tipper is ready”, may depend on a contextually-determined completion. Semantics and Pragmatics 8/4/10 Page 2 • The interpretation of a sentence containing a discourse particle such as “too”, as in “Dennis is having dinner in London tonight too”, may depend on a contextually determined set of background propositions (Gauker 2008a). • The interpretation of a sentence employing metonymy, such as “The ham sandwich wants his check”, depends on a contextually-determined relation of reference-shifting. -

VP Ellipsis Without Parallel Binding∗

Proceedings of SALT 24: 000–000, 2014 The sticky reading: VP ellipsis without parallel binding∗ Patrick D. Elliott Andreea C. Nicolae University College London ZAS Berlin Yasutada Sudo University College London Abstract VP Ellipsis (VPE) whose antecedent VP contains a pronoun famously gives rise to an ambiguity between strict and sloppy readings. Since Sag’s (1976) seminal work, it is generally assumed that the strict reading involves free pronouns in both the elided VP and its antecedent, whereas the sloppy reading involves bound pronouns. The majority of current approaches to VPE are tailored to derive this parallel binding requirement, ruling out mixed readings where one of the VPs involves a bound pronoun and the other a free pronoun in parallel positions. Contrary to this assumption, it is observed that there are cases of VPE where the antecedent VP contains a bound pronoun but the elided VP contains a free E-type pronoun anchored to the quantifier, in violation of parallel binding. We dub this the ‘sticky reading’ of VPE. To account for it, we propose a new identity condition on VPE which is less stringent than is standardly assumed. We formalize this using an extension of Roberts’s (2012) Question under Discussion (QuD) theory of information structure. Keywords: VP ellipsis, strict/sloppy identity, pronominal binding, focus, Question under Discussion 1 Introduction It has been famously observed by Sag(1976) that pronouns give rise to an ambiguity in a VP Ellipsis (VPE) context. An example such as (1) is claimed to be ambiguous between so-called strict and sloppy readings. (1) Jonny totaled his car, and Kevin did h...i too. -

Notes on Generalized Quantifiers

Notes on generalized quantifiers Ann Copestake ([email protected]), Computer Lab Copyright c Ann Copestake, 2001–2012 These notes are (minimally) adapted from lecture notes on compositional semantics used in a previous course. They are provided in order to supplement the notes from the Introduction to Natural Language Processing module on compositional semantics. 1 More on scope and quantifiers In the introductory module, we restricted ourselves to first order logic (or subsets of it). For instance, consider: (1) every big dog barks 8x[big0(x) ^ dog0(x) ) bark0(x)] This is first order because all predicates take variables denoting entities as arguments and because the quantifier (8) and connective (^) are part of standard FOL. As far as possible, computational linguists avoid the use of full higher-order logics. Theorem-proving with any- thing more than first order logic is problematic in general (though theorem-proving with FOL is only semi-decidable and that there are some ways in which higher-order constructs can be used that don’t make things any worse). Higher order sets in naive set theory also give rise to Russell’s paradox. Even without considering inference or denotation, higher-order logics cause computational problems: e.g., when deciding whether two higher order expressions are potentially equivalent (higher-order unification). However, we have to go beyond standard FOPC to represent some constructions. We need modal operators such as probably. I won’t go into the semantics of these in detail, but we can represent them as higher-order predicates. For instance: probably0(sleep0(k)) corresponds to kitty probably sleeps. -

A Type-Theoretical Analysis of Complex Verb Generation

A Type-theoretical Analysis of Complex Verb Generation Satoshi Tojo Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. 2-22 Harumi 3, Chuo-ku Tokyo 104, Japan e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract hardly find a verb element in the target language, which corresponds with the original word exactly in Tense and aspect, together with mood and modality, meaning. However we also need to admit that the usually form the entangled structure of a complex verb. problem of knowledge representation of tense and as- They are often hard to translate by machines, because pect (namely time), or that of mood and modality is of both syntactic and semantic differences between lan- not only the problem of verb translation, but that of guages. This problem seriously affects upon the gen- the whole natural language understanding. In this pa- eration process because those verb components in in- per, in order to realize a type calculus in syntax, we terlingua are hardly rearranged correctly in the target depart from a rather mundane subset of tense, aspects, language. We propose here a method in which each and modMities, which will be argued in section 2. verb element is defined as a mathematical function ac- cording to its type of type theory. This formalism gives 1.2 The difference in the structure each element its legal position in the complex verb in the target language and certifies so-called partial trans- In the Japanese translation of (1): lation. In addition, the generation algorithm is totally oyoi-de-i-ta-rashii free from the stepwise calculation, and is available on parallel architecture. -

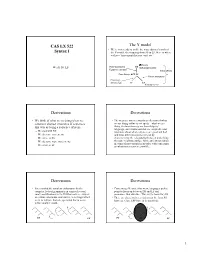

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

Making a Pronoun: Fake Indexicals As Windows Into the Properties of Pronouns Angelika Kratzer

University of Massachusetts Amherst From the SelectedWorks of Angelika Kratzer 2009 Making a Pronoun: Fake Indexicals as Windows into the Properties of Pronouns Angelika Kratzer Available at: https://works.bepress.com/angelika_kratzer/ 6/ Making a Pronoun: Fake Indexicals as Windows into the Properties of Pronouns Angelika Kratzer This article argues that natural languages have two binding strategies that create two types of bound variable pronouns. Pronouns of the first type, which include local fake indexicals, reflexives, relative pronouns, and PRO, may be born with a ‘‘defective’’ feature set. They can ac- quire the features they are missing (if any) from verbal functional heads carrying standard -operators that bind them. Pronouns of the second type, which include long-distance fake indexicals, are born fully specified and receive their interpretations via context-shifting -operators (Cable 2005). Both binding strategies are freely available and not subject to syntactic constraints. Local anaphora emerges under the assumption that feature transmission and morphophonological spell-out are limited to small windows of operation, possibly the phases of Chomsky 2001. If pronouns can be born underspecified, we need an account of what the possible initial features of a pronoun can be and how it acquires the features it may be missing. The article develops such an account by deriving a space of possible paradigms for referen- tial and bound variable pronouns from the semantics of pronominal features. The result is a theory of pronouns that predicts the typology and individual characteristics of both referential and bound variable pronouns. Keywords: agreement, fake indexicals, local anaphora, long-distance anaphora, meaning of pronominal features, typology of pronouns 1 Fake Indexicals and Minimal Pronouns Referential and bound variable pronouns tend to look the same. -

Minimal Pronouns, Logophoricity and Long-Distance Reflexivisation in Avar

Minimal pronouns, logophoricity and long-distance reflexivisation in Avar* Pavel Rudnev Revised version; 28th January 2015 Abstract This paper discusses two morphologically related anaphoric pronouns inAvar (Avar-Andic, Nakh-Daghestanian) and proposes that one of them should be treated as a minimal pronoun that receives its interpretation from a λ-operator situated on a phasal head whereas the other is a logophoric pro- noun denoting the author of the reported event. Keywords: reflexivity, logophoricity, binding, syntax, semantics, Avar 1 Introduction This paper has two aims. One is to make a descriptive contribution to the crosslin- guistic study of long-distance anaphoric dependencies by presenting an overview of the properties of two kinds of reflexive pronoun in Avar, a Nakh-Daghestanian language spoken natively by about 700,000 people mostly living in the North East Caucasian republic of Daghestan in the Russian Federation. The other goal is to highlight the relevance of the newly introduced data from an understudied lan- guage to the theoretical debate on the nature of reflexivity, long-distance anaphora and logophoricity. The issue at the heart of this paper is the unusual character of theanaphoric system in Avar, which is tripartite. (1) is intended as just a preview with more *The present material was presented at the Utrecht workshop The World of Reflexives in August 2011. I am grateful to the workshop’s audience and participants for their questions and comments. I am indebted to Eric Reuland and an anonymous reviewer for providing valuable feedback on the first draft, as well as to Yakov Testelets for numerous discussions of anaphora-related issues inAvar spanning several years. -

A Crossover Puzzle in Hindi Scrambling

Universität Leipzig November òýÔÀ A crossover puzzle in Hindi scrambling Stefan Keine University of Southern California (presenting joint work with Rajesh Bhatt) Ô Introduction Condition C, i.e., if it does not amnesty a Condition C violation in the base position (see Lebeaux ÔÀ, òýýý, Chomsky ÔÀÀç, Sauerland ÔÀÀ, Fox ÔÀÀÀ, • Background and terminology Takahashi & Hulsey òýýÀ). Ô. Inverse linking ( ) a. *He thinks [John’s mother] is intelligent. A possessor may bind a pronoun c-commanded by its host DP (May ÔÀÞÞ, Ô Ô b. * mother thinks is intelligent. Higginbotham ÔÀý, Reinhart ÔÀç). We will refer to this phenomena as [John’sÔ ]ò heÔ ò inverse linking (see May & Bale òýýâ for an overview). • Movement-type asymmetries (Ô) a. [Everyone’sÔ mother] thinks heÔ is a genius. English A- and A-movement dier w.r.t. several of these properties: b. [No one’s mother-in-law] fully approves of her . Ô Ô (â) Weak crossover (WCO) ò. Crossover a. A-movement Crossover arises if a DP moves over a pronoun that it binds and the resulting Every boyÔ seems to hisÔ mother [ Ô to be intelligent ] structure is ungrammatical (Postal ÔÀÞÔ, Wasow ÔÀÞò). b. A-movement (ò) Strong crossover (SCO): pronoun c-commands trace *Which boyÔ did hisÔ mother say [ Ô is intelligent ]? a. *DPÔ ... pronÔ ... tÔ (Þ) Secondary strong crossover (SSCO) b. *WhoÔ does sheÔ like Ô? a. A-movement (ç) Weak crossover (WCO): pronoun does not c-command trace [ Every boy’sÔ mother ]ò seems to himÔ [ ò to be intelligent ] a. *DP ... [ ... pron ...] ... t Ô DP Ô Ô b. -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(S): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol

MIT Press Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(s): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Autumn, 1989), pp. 555-588 Published by: MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4178645 Accessed: 22-10-2015 18:32 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Linguistic Inquiry. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.97.27.20 on Thu, 22 Oct 2015 18:32:27 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Hilda Koopman Pronouns, Logical Variables, Dominique Sportiche and Logophoricity in Abe 1. Introduction 1.1. Preliminaries In this article we describe and analyze the propertiesof the pronominalsystem of Abe, a Kwa language spoken in the Ivory Coast, which we view as part of the study of pronominalentities (that is, of possible pronominaltypes) and of pronominalsystems (that is, of the cooccurrence restrictionson pronominaltypes in a particulargrammar). Abe has two series of thirdperson pronouns. One type of pronoun(0-pronoun) has basically the same propertiesas pronouns in languageslike English. The other type of pronoun(n-pronoun) very roughly corresponds to what has been called the referential use of pronounsin English(see Evans (1980)).It is also used as what is called a logophoric pronoun-that is, a particularpronoun that occurs in special embedded contexts (the logophoric contexts) to indicate reference to "the person whose speech, thought or perceptions are reported" (Clements (1975)). -

Scope Or Pseudoscope? Are There Wide-Scope Indefinites?1

1 Scope or Pseudoscope? Are there Wide-Scope Indefinites?1 Angelika Kratzer, University of Massachusetts at Amherst March 1997 1. The starting point: Fodor and Sag My story begins with a famous example by Janet Fodor and Ivan Sag 2: The Fodor and Sag example (1) Each teacher overheard the rumor that a student of mine had been called before the dean. (1) has a reading where the indefinite NP a student of mine has scope within the that - clause. What the teachers overheard might have been: “A student of Angelika’s was called before the dean”. This reading is expected if indefinite NPs are quantifiers, and quantifier scope is confined to some local domain. (1) has another reading where a student of mine seems to have widest scope, scope even wider than each teacher. There might have been a student of mine, say Sanders, and each teacher overheard the rumor that Sanders was called before the dean. Fodor and Sag argue that this is not an instance of scope. If indefinite NPs seem to have anomalous scope properties, they are not true quantifiers. The apparent wide-scope reading of a student of mine in (1) is really a referential reading. Indefinite NPs, then, are ambiguous between quantificational and referential readings. If they are quantificational, their scope cannot exceed some local domain. If they are referential, they do not have scope at all. They may be easily confused with widest scope existentials, however. Sentence (1) is important for Fodor and Sag’s argument since it offers a third scope possibility for the indefinite NP that doesn’t seem to be there.