Reading Capital Politically

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WEB KARAOKE EN-NL.Xlsx

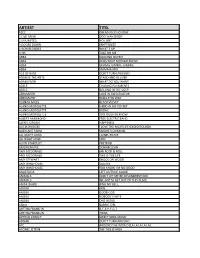

ARTIEST TITEL 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 2 LIVE CREW DOO WAH DIDDY 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP A HA TAKE ON ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA DOES YOUR MOTHER KNOW ABBA GIMMIE GIMMIE GIMMIE ABBA MAMMA MIA ACE OF BASE DON´T TURN AROUND ADAM & THE ANTS STAND AND DELIVER ADAM FAITH WHAT DO YOU WANT ADELE CHASING PAVEMENTS ADELE ROLLING IN THE DEEP AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR AEROSMITH WALK THIS WAY ALANAH MILES BLACK VELVET ALANIS MORISSETTE HAND IN MY POCKET ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW ALBERT HAMMOND FREE ELECTRIC BAND ALEXIS JORDAN HAPPINESS ALICIA BRIDGES I LOVE THE NIGHTLIFE (DISCO ROUND) ALIEN ANT FARM SMOOTH CRIMINAL ALL NIGHT LONG LIONEL RICHIE ALL RIGHT NOW FREE ALVIN STARDUST PRETEND AMERICAN PIE DON MCLEAN AMY MCDONALD MR ROCK & ROLL AMY MCDONALD THIS IS THE LIFE AMY STEWART KNOCK ON WOOD AMY WINEHOUSE VALERIE AMY WINEHOUSE YOU KNOW I´M NO GOOD ANASTACIA LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE ANIMALS DON´T LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD ANIMALS WE GOTTA GET OUT OF THIS PLACE ANITA WARD RING MY BELL ANOUK GIRL ANOUK GOOD GOD ANOUK NOBODY´S WIFE ANOUK ONE WORD AQUA BARBIE GIRL ARETHA FRANKLIN R-E-S-P-E-C-T ARETHA FRANKLIN THINK ARTHUR CONLEY SWEET SOUL MUSIC ASWAD DON´T TURN AROUND ATC AROUND THE WORLD (LA LA LA LA LA) ATOMIC KITTEN THE TIDE IS HIGH ARTIEST TITEL ATOMIC KITTEN WHOLE AGAIN AVRIL LAVIGNE COMPLICATED AVRIL LAVIGNE SK8TER BOY B B KING & ERIC CLAPTON RIDING WITH THE KING B-52´S LOVE SHACK BACCARA YES SIR I CAN BOOGIE BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE YOU AIN´T SEEN NOTHING YET BACKSTREET BOYS -

Billboard-1997-08-30

$6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) $5.95 (U.S.), IN MUSIC NEWS BBXHCCVR *****xX 3 -DIGIT 908 ;90807GEE374EM0021 BLBD 595 001 032898 2 126 1212 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE APT A LONG BEACH CA 90807 Hall & Oates Return With New Push Records Set PAGE 1 2 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT AUGUST 30, 1997 ADVERTISEMENTS 4th -Qtr. Prospects Bright, WMG Assesses Its Future Though Challenges Remain Despite Setbacks, Daly Sees Turnaround BY CRAIG ROSEN be an up year, and I think we are on Retail, Labels Hopeful Indies See Better Sales, the right roll," he says. LOS ANGELES -Warner Music That sense of guarded optimism About New Releases But Returns Still High Group (WMG) co- chairman Bob Daly was reflected at the annual WEA NOT YOUR BY DON JEFFREY BY CHRIS MORRIS looks at 1997 as a transitional year for marketing managers meeting in late and DOUG REECE the company, July. When WEA TYPICAL LOS ANGELES -The consensus which has endured chairman /CEO NEW YORK- Record labels and among independent labels and distribu- a spate of negative m David Mount retailers are looking forward to this tors is that the worst is over as they look press in the last addressed atten- OPEN AND year's all- important fourth quarter forward to a good holiday season. But few years. Despite WARNER MUSI C GROUP INC. dees, the mood with reactions rang- some express con- a disappointing was not one of SHUT CASE. ing from excited to NEWS ANALYSIS cern about contin- second quarter that saw Warner panic or defeat, but clear -eyed vision cautiously opti- ued high returns Music's earnings drop 24% from last mixed with some frustration. -

Marketocracy and the Capture of People and Planet

The Jus Semper Global Alliance In Pursuit of the People and Planet Paradigm Sustainable Human Development July 2021 BRIEFS ON TRUE DEMOCRACY AND CAPITALISM Marketocracy and the Capture of People and Planet The acceleration of Twenty-First Century Monopoly Capital Fascism through the pandemic and the Great Reset Álvaro J. de Regil TJSGA/Assessment/SD (TS010) July 2021/Álvaro J. de Regil 1 Prologue Prologue... 2 ❖ Capitalism’s Journey of Dehumanisation... 6 n innate feature of capitalism has been the endless First Industrial Revolution... 6 A pursuit of an ethos with the least possible intervention Second Industrial Revolution... 10 of the state in its unrelenting quest for the reproduction and Third Industrial Revolution... 16 accumulation of capital, at the expense of all other participants ➡Modern Slave Work Stuctures… 20 in the economic activity prominently including the planet. ➡The Anthropocene… 23 Capitalism always demands to be in the driver's seat of the ❖ The Capture of Democracy… 29 economy. Only when its activities are threatened by ➡Sheer Laissez-Faire Ethos… 33 communities and nations opposing the expropriation of their ➡Capital Equated with Human Beings… 34 natural resources and the imposition of structures that extract ➡Untramelled and Imposed Marketrocratic System... 35 the vast majority of the value of labour—the surplus-value—, ❖ Fourth Industrial Revolution... 39 capitalism demands the intervention of the states; these include ➡Conceptual Structure… 41 their armed forces, to protect the exploits of the owners of the ➡Application… 42 system. This is all the more evident in the global South. Across ➡Impact… 44 centuries of imperialism and colonialism, the practice of ❖ The COVID-19 Pandemic… 59 invasion, conquering, expropriation and exploitation by ➡Management of COVID-19.. -

Songs by Artist 08/29/21

Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Alexander’s Ragtime Band DK−M02−244 All Of Me PM−XK−10−08 Aloha ’Oe SC−2419−04 Alphabet Song KV−354−96 Amazing Grace DK−M02−722 KV−354−80 America (My Country, ’Tis Of Thee) ASK−PAT−01 America The Beautiful ASK−PAT−02 Anchors Aweigh ASK−PAT−03 Angelitos Negros {Spanish} MM−6166−13 Au Clair De La Lune {French} KV−355−68 Auld Lang Syne SC−2430−07 LP−203−A−01 DK−M02−260 THMX−01−03 Auprès De Ma Blonde {French} KV−355−79 Autumn Leaves SBI−G208−41 Baby Face LP−203−B−07 Beer Barrel Polka (Roll Out The Barrel) DK−3070−13 MM−6189−07 Beyond The Sunset DK−77−16 Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home? DK−M02−240 CB−5039−3−13 B−I−N−G−O CB−DEMO−12 Caisson Song ASK−PAT−05 Clementine DK−M02−234 Come Rain Or Come Shine SAVP−37−06 Cotton Fields DK−2034−04 Cry Like A Baby LAS−06−B−06 Crying In The Rain LAS−06−B−09 Danny Boy DK−M02−704 DK−70−16 CB−5039−2−15 Day By Day DK−77−13 Deep In The Heart Of Texas DK−M02−245 Dixie DK−2034−05 ASK−PAT−06 Do Your Ears Hang Low PM−XK−04−07 Down By The Riverside DK−3070−11 Down In My Heart CB−5039−2−06 Down In The Valley CB−5039−2−01 For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow CB−5039−2−07 Frère Jacques {English−French} CB−E9−30−01 Girl From Ipanema PM−XK−10−04 God Save The Queen KV−355−72 Green Grass Grows PM−XK−04−06 − 1 − Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Greensleeves DK−M02−235 KV−355−67 Happy Birthday To You DK−M02−706 CB−5039−2−03 SAVP−01−19 Happy Days Are Here Again CB−5039−1−01 Hava Nagilah {Hebrew−English} MM−6110−06 He’s Got The Whole World In His Hands -

Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution

Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 2 2021 Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Chris Wright [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Chris (2021) "Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.9.1.009647 Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol9/iss1/2 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Abstract In the twenty-first century, it is time that Marxists updated the conception of socialist revolution they have inherited from Marx, Engels, and Lenin. Slogans about the “dictatorship of the proletariat” “smashing the capitalist state” and carrying out a social revolution from the commanding heights of a reconstituted state are completely obsolete. In this article I propose a reconceptualization that accomplishes several purposes: first, it explains the logical and empirical problems with Marx’s classical theory of revolution; second, it revises the classical theory to make it, for the first time, logically consistent with the premises of historical materialism; third, it provides a (Marxist) theoretical grounding for activism in the solidarity economy, and thus partially reconciles Marxism with anarchism; fourth, it accounts for the long-term failure of all attempts at socialist revolution so far. -

Restructuring the Socialist Economy

CAPITAL AND CLASS IN CUBAN DEVELOPMENT: Restructuring the Socialist Economy Brian Green B.A. Simon Fraser University, 1994 THESISSUBMllTED IN PARTIAL FULFULLMENT OF THE REQUIREMEW FOR THE DEGREE OF MASER OF ARTS Department of Spanish and Latin American Studies O Brian Green 1996 All rights resewed. This work my not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Siblioth&ye nationale du Canada Azcjuis;lrons and Direction des acquisitions et Bitjibgraphic Sewices Branch des services biblicxpphiques Youi hie Vofrergfereoce Our hie Ncfre rb1Prence The author has granted an L'auteur a accorde une licence irrevocable non-exclusive ficence irrevocable et non exclusive allowing the National Library of permettant & la Bibliotheque Canada to reproduce, loan, nationafe du Canada de distribute or sell copies of reproduire, preter, distribuer ou his/her thesis by any means and vendre des copies de sa these in any form or format, making de quelque maniere et sous this thesis available to interested quelque forme que ce soit pour persons. mettre des exemplaires de cette these a la disposition des personnes int6ress6es. The author retains ownership of L'auteur consenre la propriete du the copyright in his/her thesis. droit d'auteur qui protege sa Neither the thesis nor substantial th&se. Ni la thbe ni des extraits extracts from it may be printed or substantiefs de celle-ci ne otherwise reproduced without doivent 6tre imprimes ou his/her permission. autrement reproduits sans son autorisatiow. PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Sion Fraser Universi the sight to Iend my thesis, prosect or ex?ended essay (the title o7 which is shown below) to users o2 the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the Zibrary of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. -

THE POLITICAL THOUGHT of the THIRD WORLD LEFT in POST-WAR AMERICA a Dissertation Submitted

LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Washington, DC August 6, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Benjamin Feldman All Rights Reserved ii LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Michael Kazin, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the full intellectual history of the Third World Turn: when theorists and activists in the United States began to look to liberation movements within the colonized and formerly colonized nations of the ‘Third World’ in search of models for political, social, and cultural transformation. I argue that, understood as a critique of the limits of New Deal liberalism rather than just as an offshoot of New Left radicalism, Third Worldism must be placed at the center of the history of the post-war American Left. Rooting the Third World Turn in the work of theorists active in the 1940s, including the economists Paul Sweezy and Paul Baran, the writer Harold Cruse, and the Detroit organizers James and Grace Lee Boggs, my work moves beyond simple binaries of violence vs. non-violence, revolution vs. reform, and utopianism vs. realism, while throwing the political development of groups like the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, and the Third World Women’s Alliance into sharper relief. -

JSR 2-2 E.Indd

Restoring the Garden of Eden in England’s Green and Pleasant Land: The Diggers and the Fruits of the Earth ■ Ariel Hessayon, Goldsmiths, University of London Th is Land which was barren and wast is now become fruitfull and pleasant like the Garden of Eden —Th e Kingdomes Faithful and Impartiall Scout1 I will not cease from Mental Fight, Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand: Till we have built Jerusalem, In Englands green & pleasant Land —William Blake, ‘Preface’ to ‘Milton’2 I. The Diggers, 1649–50 On Sunday, 1 or perhaps 8 April 1649—it is difficult to establish the date with certainty—five people went to St. George’s Hill in the parish Walton-on- Th ames, Surrey, and began digging the earth. Th ey “sowed” the ground with parsnips, carrots, and beans, returning the next day in increased numbers. Th e following day they burned at least 40 roods of heath, which was considered “a very great prejudice” to the town. By the end of the week between 20 and 30 people were reportedly laboring the entire day at digging. It was said that they intended to plow up the ground and sow it with seed corn. Furthermore, they apparently threatened to pull down and level all park pales and “lay all open,” thereby evoking fears of an anti-enclosure riot (a familiar form Journal for the Study of Radicalism, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2008, pp. 1–25. issn 1930-1189. © Michigan State University. 1 2 Ariel Hessayon of agrarian protest).3 Th e acknowledged leaders of these “new Levellers” or “diggers” were William Everard (1602?–fl.1651) and Gerrard Winstanley (1609–76). -

I4P Rochdale Community Champions Building Community Knowledge, Developing Community Research

Rochdale Community Champions Building Community Knowledge, Developing Community Research in 2015 I4P Rochdale Community Champions Building Community Knowledge, Developing Community Research Rochdale Community Champions Building Community Knowledge, Developing Community Research Edited by Katy Goldstraw, Helen Chicot and John Diamond Contents 05 Foreword, Steve Rumbelow 06 Who Are Rochdale Community Champions? 07 The Leadership and Participatory Research Methods Training 08 Rochdale Community Champions: Adult and Continuing Education in action 09 Participatory Research: Principles and Practice 11 The Research: Case Studies 12 1. Yasmin and Andrew 29 2. Chris 32 3. Jan 39 4. Julia 45 5. Norma 45 The Research Process 48 Afterword, John Cater 49 Appendix One: Proposal from Edge Hill University to work with Rochdale Community Champions 51 Appendix Two - Four: Session Planners 53 Appendix Five: Who is Who and How to find out more 2 3 Rochdale Community Champions Building Community Knowledge, Developing Community Research Foreword to the Project Steve Rumbelow, Chief Executive, Rochdale Borough Council. This is the second booklet to come from the joint work between Edge Hill University and the Rochdale Borough Community Champions. It is an illustration of the deep thinking and hard work that our Community Champions put into their role; not just through the help they give to others as volunteers but also through the careful thought and care that sits behind that. This booklet provides us with some examples of what it means to be a Community Champion. It tells us that who you are and what you think and believe is an important element of what you do. Public services are facing very challenging times and are having to find new and better delivery models, which work to support confident and resilient communities. -

Breaking the Spell

Praise for Breaking the Spell “Christopher Robé’s meticulously researched Breaking the Spell traces the roots of contemporary, anarchist-inflected video and Internet activism and clearly demonstrates the affinities between the anti-authoritarian ethos and aesthetic of collectives from the ’60s and ’70s—such as Newsreel and the Videofreex—and their contemporary descendants. Robé’s nuanced perspective enables him to both celebrate and critique anarchist forays into guerrilla media. Breaking the Spell is an invaluable guide to the contempo- rary anarchist media landscape that will prove useful for activists as well as scholars.” —Richard Porton, author of Film and the Anarchist Imagination “Breaking the Spell is a highly readable history of U.S. activism against neo- liberal capitalism from the perspective of ‘Anarchist Filmmakers, Videotape Guerrillas, and Digital Ninjas,’ the subtitle of the book. Based on ninety interviews, careful readings of hundreds of videos, and his own participant observation, Robé links the development of better-known video makers such as Videofreex, Paper Tiger Television, ACT UP and Indymedia with activist media makers among key protest movements, such as the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in Detroit, Oregon’s Cascadia Forest Defenders, the day workers of Voces Mobiles/Mobile Voices in Los Angeles, and the indigenous youth in Outta Your Backpack Media. Underscored by significant tensions of class, race/ethnicity, and gender among the groups and the videos discussed, Robé traces the continuing concerns -

Towards a Unified Theory Analysing Workplace Ideologies: Marxism And

Marxism and Racial Oppression: Towards a Unified Theory Charles Post (City University of New York) Half a century ago, the revival of the womens movementsecond wave feminismforced the revolutionary left and Marxist theory to revisit the Womens Question. As historical materialists in the 1960s and 1970s grappled with the relationship between capitalism, class and gender, two fundamental positions emerged. The dominant response was dual systems theory. Beginning with the historically correct observation that male domination predates the emergence of the capitalist mode of production, these theorists argued that contemporary gender oppression could only be comprehended as the result of the interaction of two separate systemsa patriarchal system of gender domination and the capitalist mode of production. The alternative approach emerged from the debates on domestic labor and the predominantly privatized character of the social reproduction of labor-power under capitalism. In 1979, Lise Vogel synthesized an alternative unitary approach that rooted gender oppression in the tensions between the increasingly socialized character of (most) commodity production and the essentially privatized character of the social reproduction of labor-power. Today, dual-systems theory has morphed into intersectionality where distinct systems of class, gender, sexuality and race interact to shape oppression, exploitation and identity. This paper attempts to begin the construction of an outline of a unified theory of race and capitalism. The paper begins by critically examining two Marxian approaches. On one side are those like Ellen Meiksins Wood who argued that capitalism is essentially color-blind and can reproduce itself without racial or gender oppression. On the other are those like David Roediger and Elizabeth Esch who argue that only an intersectional analysis can allow historical materialists to grasp the relationship of capitalism and racial oppression. -

Automation and the Meaning of Work in the Postwar United States

The Misanthropic Sublime: Automation and the Meaning of Work in the Postwar United States Jason Resnikoff Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Jason Zachary Resnikoff All rights reserved Abstract “The Misanthropic Sublime: Automation and the Meaning of Work in the Postwar United States” Jason Resnikoff In the United States of America after World War II, Americans from across the political spectrum adopted the technological optimism of the postwar period to resolve one of the central contradictions of industrial society—the opposition between work and freedom. Although classical American liberalism held that freedom for citizens meant owning property they worked for themselves, many Americans in the postwar period believed that work had come to mean the act of maintaining mere survival. The broad acceptance of this degraded meaning of work found expression in a word coined by managers in the immediate postwar period: “automation.” Between the late 1940s and the early 1970s, the word “automation” stood for a revolutionary development, even though few could agree as to precisely what kind of technology it described. Rather than a specific technology, however, this dissertation argues that “automation” was a discourse that defined work as mere biological survival and saw the end of human labor as the the inevitable result of technological progress. In premising liberation on the end of work, those who subscribed to the automation discourse made political freedom contingent not on the distribution of power, but on escape from the limits of the human body itself.