UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Erotic Negativity and Victorian Aestheticism, 1864-1896 a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPENDIX 1 April 2018 to March 2021 Recommendations for the Community and Voluntary Organisations Grants Commissioning Programme

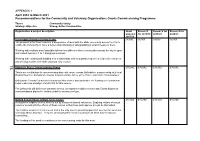

APPENDIX 1 April 2018 to March 2021 Recommendations for the Community and Voluntary Organisations Grants Commissioning Programme Theme Community Safety Strategic Objective Strong, Active Communities Organisation & project description Grant Recom’d Recom’d for Recom’d for awarded for 2018/19 2019/20 2020/21 2017/18 Donnington Doorstep Family Centre £8,000 £8,000 £8,000 £8,000 The proposal is for them to deliver a programme of work with the BME community across the City to enable the community to have a better understanding of safeguarding at what it means to them. Working with mothers and if possible fathers from different ethnic communities across the city in open and closed sessions, 1 to 1 and group sessions. Working with existing and building new relationships with local partner agencies to identify resources and develop toolkits on behalf of Oxford City Council. 75 Domestic Abuse Commissioning Group £35,082 £35,082 £35,082 £35,082 This is our contribution to commissioning domestic abuse across Oxfordshire in partnership with local District Councils, Oxfordshire County Council and the Office of the Police and Crime Commissioner. Oxfordshire County Council will commission this service and administer the funding our contribution helps makes up a budget of £600,000 for this service. For Oxford this will deliver an outreach service, a telephone helpline service and 5 local dispersed accommodation places for victims unable to access a refuge. Oxford Sexual Abuse & Rape Crisis Centre £15,000 £15,000 £15,000 £15,000 A telephone helpline service which is run by a team of trained volunteers. Enabling victims of sexual violence to deal with the effects of these crimes in their lives and improve access to information. -

Nietzsche and Aestheticism

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1992 Nietzsche and Aestheticism Brian Leiter Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Brian Leiter, "Nietzsche and Aestheticism," 30 Journal of the History of Philosophy 275 (1992). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Notes and Discussions Nietzsche and Aestheticism 1o Alexander Nehamas's Nietzsche: L~fe as Literature' has enjoyed an enthusiastic reception since its publication in 1985 . Reviewed in a wide array of scholarly journals and even in the popular press, the book has won praise nearly everywhere and has already earned for Nehamas--at least in the intellectual community at large--the reputation as the preeminent American Nietzsche scholar. At least two features of the book may help explain this phenomenon. First, Nehamas's Nietzsche is an imaginative synthesis of several important currents in recent Nietzsche commentary, reflecting the influence of writers like Jacques Der- rida, Sarah Kofman, Paul De Man, and Richard Rorty. These authors figure, often by name, throughout Nehamas's book; and it is perhaps Nehamas's most important achievement to have offered a reading of Nietzsche that incorporates the insights of these writers while surpassing them all in the philosophical ingenuity with which this style of interpreting Nietzsche is developed. The high profile that many of these thinkers now enjoy on the intellectual landscape accounts in part for the reception accorded the "Nietzsche" they so deeply influenced. -

Art for Art's Sake: a Literary Luxury Or a Contemporaneous Need?

International Journal of Language and Literature December 2018, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 182-187 ISSN: 2334-234X (Print), 2334-2358 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijll.v6n2a27 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/ijll.v6n2a27 Art for Art’s Sake: A Literary Luxury or a Contemporaneous Need? Dr. Mohamad Haj Mohamad1 & Dr. Nadia Hamendi2 Abstract The dichotomy of art for art‘s sake and art for society‘s sake became a pressing concern in the Victorian period due to the pressure from government to use art as a means for championing its causes and aspirations, leaving artists feeling the need to redefine the identity and objectives of art. Believing in art as serving the creation only of beauty for its own sake led to the emergence and rise of art for art‘s sake, a movement that felt that art stripped of its true aesthetical values would suffer as a result. Art for art's sake is an assertion of the value of art away from any moral or didactic objectives, a process that adds a mask of luxury to literature. This paper traces the movement of art for art‘s sake, looking at its main figures from across Europe. It poses the question of whether art is supposed to moralize and teach or devote itself to the creation and championing of the cause of beauty and idealism. Believing that art had declined in an era of utility and rationalism, rebellion against Victorian middle class moral standards was unavoidable. -

On the Methodological Role of Marxism in Merleau-Ponty's

On the Methodological Role of Marxism in Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology Abstract While contemporary scholarship on Merleau-Ponty virtually overlooks his postwar existential Marxism, this paper argues that the conception of history contained in the latter plays a signifi- cant methodological role in supporting the notion of truth that operates within Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological analyses of embodiment and the perceived world. This is because this con- ception regards the world as an unfinished task, such that the sense and rationality attributed to its historical emergence conditions the phenomenological evidence used by Merleau-Ponty. The result is that the content of Phenomenology of Perception should be seen as implicated in the normative framework of Humanism and Terror. Keywords: Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology, Methodology, Marxism, History On the Methodological Role of Marxism in Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology In her 2007 book Merleau-Ponty and Modern Politics after Anti-Humanism, Diana Coole made the claim (among others) that Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology is “profoundly and intrinsically political,”1 and in particular that it would behoove readers of his work to return to the so-called ‘communist question’ as he posed it in the immediate postwar period.2 For reasons that basical- ly form the substance of this paper, I think that these claims are generally correct and well- taken. But this is in spite of the fact that they go very distinctly against the grain of virtually all contemporary scholarship on Merleau-Ponty. For it is the case that very few scholars today – and this is particularly true of philosophers – have any serious interest in the political dimen- sions of Merleau-Ponty’s work. -

English Renaissance

1 ENGLISH RENAISSANCE Unit Structure: 1.0 Objectives 1.1 The Historical Overview 1.2 The Elizabethan and Jacobean Ages 1.2.1 Political Peace and Stability 1.2.2 Social Development 1.2.3 Religious Tolerance 1.2.4 Sense and Feeling of Patriotism 1.2.5 Discovery, Exploration and Expansion 1.2.6 Influence of Foreign Fashions 1.2.7 Contradictions and Set of Oppositions 1.3 The Literary Tendencies of the Age 1.3.1 Foreign Influences 1.3.2 Influence of Reformation 1.3.3 Ardent Spirit of Adventure 1.3.4 Abundance of Output 1.4 Elizabethan Poetry 1.4.1 Love Poetry 1.4.2 Patriotic Poetry 1.4.3 Philosophical Poetry 1.4.4 Satirical Poetry 1.4.5 Poets of the Age 1.4.6 Songs and Lyrics in Elizabethan Poetry 1.4.7 Elizabethan Sonnets and Sonneteers 1.5 Elizabethan Prose 1.5.1 Prose in Early Renaissance 1.5.2 The Essay 1.5.3 Character Writers 1.5.4 Religious Prose 1.5.5 Prose Romances 2 1.6 Elizabethan Drama 1.6.1 The University Wits 1.6.2 Dramatic Activity of Shakespeare 1.6.3 Other Playwrights 1.7. Let‘s Sum up 1.8 Important Questions 1.0. OBJECTIVES This unit will make the students aware with: The historical and socio-political knowledge of Elizabethan and Jacobean Ages. Features of the ages. Literary tendencies, literary contributions to the different of genres like poetry, prose and drama. The important writers are introduced with their major works. With this knowledge the students will be able to locate the particular works in the tradition of literature, and again they will study the prescribed texts in the historical background. -

LGBTQ+ Campaign

LGBTQ+ Campaign LGBTQ+ Campaign 1 CONTENTS INTRO 4 What is this and who is it for? 4 ADMINISTRATIVE QUESTIONS 5 How do I change my gender marker on my student record? 5 How do I change my name on my student record? 6 How do I change my title? 8 How do I change my name on my University Card(BodCard)? 8 Can I change the photo on my BodCard? 9 How do I change my name on my email? 10 How do I get my name changed on my pigeon hole (‘pidge’)? 11 What name will appear on my Degree Certificate? 11 How do I change my pronouns? 12 What records do college/the University keep of my name and gender marker? 12 What do I need to do to (re-)register to vote once I’ve changed my name? 13 HEALTH CARE QUESTIONS 14 How/where can I access trans-friendly doctors and healthcare? 14 Am I allowed to take time of for transitional purposes? 15 2 TRANS STUDENT OXFORD SURVIVAL GUIDE WELFARE QUESTIONS 16 How should I inform my academic tutors about my change of gender and/or name? 16 Which members of staf are a good point of contact? 17 Who can I talk to for welfare? Is there any student support in college? 19 FINANCE QUESTIONS 20 Can I apply for a transition fund through college? 20 What should I do if I’m facing financial dificulties because of my gender identity? 21 What should I do if my course involves travel abroad? 22 How do I change my name and gender with Student Finance England? 22 Do I need to buy a new sub fusc? 23 SOCIAL / OTHER QUESTIONS 23 Which hairdressers in Oxford are trans-friendly? 23 Where can I find gender-neutral toilets in town? 24 Are there any trans-inclusive sports groups? 25 Where can I find more support? 26 MY RIGHTS 28 What are my rights? 28 How do I report harassment? 29 Where can I find more information? 30 LGBTQ+ Campaign 3 INTRO What is this and who is it for? This is a guide put together by the Oxford SU LGBTQ+ Campaign’s Trans Rep of 2017/18 to provide practical information for trans students that should help them with various aspects of their transition in college and university. -

Attachment Data/File/404748/Align Change of Name G Uidance - V1 0.Pdf

Application: University of Oxford 2020 Workplace Equality Index Summary ID: A-1607368893 Last submitted: 9 Sep 2019 10:44 AM (UTC) Section 1: Employee Policy Completed - 16 Mar 2020 Workplace Equality Index submission Policies and Benefits: Part 1 Section 1: Policies and Benefits This section comprises of 7 questions and examines the policies and benefits the organisation has in place to support LGBT staff. The questions scrutinise policy audit process, policy content and communication. This section is worth 7.5% of your total score. Below each question you can see guidance on content and evidence. At any point, you may save and exit the form using the buttons at the bottom of the page. 1 / 135 1.1 Does the organisation have an audit process to ensure relevant policies (for example, HR policies) are explicitly inclusive of same-sex couples and use gender neutral language? GUIDANCE: The audit process should be systematic in its implementation across all relevant policies. Relevant policies include HR policies, for example leave policies. Yes Please describe the audit process: State when the process last happened: A proportionate review date is agreed for policies when they are created e.g. the Harassment Policy and Procedure has a three year review date (revised in 2014 and 2017). Describe the audit process: Governance at Oxford is democratic and its 70+ policies have been through a rigorous and widespread consultation and audit process in their creation and subsequent reviews. The process can take anything from six months to three years. With this in mind audits are not run concurrently. -

Body and Politics

The Body and Politics Oxford Handbooks Online The Body and Politics Diana Coole The Oxford Handbook of Gender and Politics Edited by Georgina Waylen, Karen Celis, Johanna Kantola, and S. Laurel Weldon Print Publication Date: Mar 2013 Subject: Political Science, Comparative Politics, Political Theory Online Publication Date: Aug 2013 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199751457.013.0006 Abstract and Keywords This article focuses on the concept of the body in political thought, which has been widely ignored. In gender studies, however, the body serves as a relevant dimension of politics. Some of the main approaches to the body in the field of gender studies were created by feminists, and emphasis has been placed on women’s embodiment. The article addresses the theoretical questions that arise when the (gendered–sexed) body is brought into political life and discourse and then summarizes several lasting questions and lists some distinctive approaches. Finally, using a study of representative authors and texts, it presents a detailed analysis of these approaches. Keywords: body, political thought, gender studies, women’s embodiment, gendered, sexed (p. 165) Introduction There is a vital sense in which humans are their bodies. We experience their demands and are made constantly aware of how others observe their appearances and abilities. Yet the body has been widely neglected in political thought and it is a notable success of gender studies that it has retrieved the body as a significant dimension of politics. The main approaches to the body in the field of gender studies were forged by feminists, with specific emphasis on women’s embodiment: a necessary but risky strategy inasmuch as women’s oppression has conventionally been founded on their identification with carnality. -

Questioning New Materialisms (3).Pdf

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Devellennes, Charles and Dillet, Benoît (2018) Questioning New Materialisms: An Introduction. Theory, Culture & Society . ISSN 0263-2764. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276418803432 Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/69492/ Document Version Author's Accepted Manuscript Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Questioning New Materialisms In their New Materialisms, Diana Coole and Samantha Frost put together a sustained and coherent theory around a number of vitalist and materialist studies that were emerging as novel ways of thinking about matter. Driven by scientific and technological advances they sought to rehabilitate matter from the oubliettes of history, and to reinstate insights from the great materialists of the nineteenth century (Marx, Nietzsche and Freud), fusing these two areas together to form this new materialism (Coole and Frost, 2010: 5). -

The Single Equality Scheme Report of Public Engagement May 2009

APPENDIX 2 The Single Equality Scheme Report of Public Engagement May 2009 Author(s) Sara Price, Communications & Engagement Project Coordinator Status Final version Date 31st May 2009 Contents 1. ABOUT OXFORDSHIRE PCT............................................................................................- 3 - 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...................................................................................................- 4 - 2.1 BACKGROUND..................................................................................................................- 4 - 2.2 PURPOSE OF THE PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT REPORT.......................................................................- 4 - 2.3 PURPOSE OF ENGAGEMENT.................................................................................................- 4 - 2.4 PROCESS & METHODOLOGY................................................................................................- 5 - 2.5 KEY FINDINGS .................................................................................................................- 5 - 2.6 CONCLUSION...................................................................................................................- 6 - 3. BACKGROUND.................................................................................................................- 7 - 3.1 THE WIDER CONTEXT.........................................................................................................- 7 - Defining equality and diversity ...........................................................................................- -

The Agency of Assemblages and the North American Blackout

The Agency of Assemblages and the North American Blackout Jane Bennett The Agency of Assemblages Globalization names a state of affairs in which Earth, no longer simply an eco- logical or geological category, has become a salient unit of political analysis. More than locality or nation, Earth is the whole in which the parts (e.g., finance capital, CO2 emissions, refugees, viruses, pirated DVDs, ozone, human rights, weapons of mass destruction) now circulate. There have been various attempts to theorize this complex, gigantic whole and to characterize the kind of relationality obtaining between its parts. Network is one such attempt, as is Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s empire.1 My term of choice to describe this whole and its style of structuration, is, following Gilles Deleuze, the assemblage.2 I am grateful to Natalie Baggs, Diana Coole, William Connolly, Ben Corson, Jennifer Culbert, Ann Curthoys, John Docker, Ruby Lal, Patchen Markell, Gyanendra Pandey, Paul Saurette, Michael Shapiro, and the editorial committee of Public Culture for their contributions to this essay. 1. See Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2001) and Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire (New York: Penguin, 2004). 2. An assemblage is, first, an ad hoc grouping, a collectivity whose origins are historical and circumstantial, though its contingent status says nothing about its efficacy, which can be quite strong. An assemblage is, second, a living, throbbing grouping whose coherence coexists with energies and countercultures that exceed and confound it. An assemblage is, third, a web with an uneven topography: some of the points at which the trajectories of actants cross each other are more heavily trafficked than others, and thus power is not equally distributed across the assemblage. -

Final Version

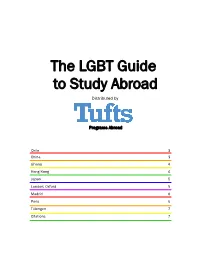

The LGBT Guide to Study Abroad Distributed by Programs Abroad Chile 3 China 3 Ghana 4 Hong Kong 4 Japan 5 London; Oxford 5 Madrid 6 Paris 6 Tübingen 7 Citations 7 Dear Student, The Pew Research Center conducted a world-wide survey between March and May of 2013 on the subject of homo- sexuality. They asked 37,653 participants in 39 countries, “Should society accept homosexuality?” The results, summariZed in this graphic, are revealing. There is a huge variance by region; some countries are extremely divided on the issue. Others have been, and continue to be, widely accepting of homosexuality. This information is relevant not only to residents of these countries, but to travelers and students who will be studying abroad. Students going abroad should be prepared for noted differences in attitudes toward individuals. Before depar- ture, it can be helpful for LGBT students to research cur- rent events pertaining to LGBT rights, general tolerance of LGBT persons, legal protection of LGBT individuals, LGBT organizations and support systems, and norms in the host culture’s dating scene. We hope that the following summaries will provide a starting point for the LGBT student’s exploration of their destination’s culture. If students are in homestay situations, they should consider the implications of coming out to their host family. Students may choose to conceal their sexual orientation to avoid tension in the student-host family relationship. Other times, students have used their time away from their home culture as an opportunity to come out. Some students have even described coming out overseas as a liberating experience, akin to a “second” coming out.