Copyright by Jeanette Marie Herman 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

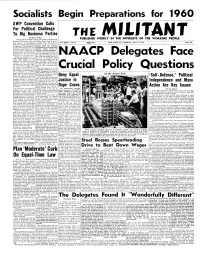

Socialists Begin Preparations for 1960

Socialists Begin Preparations for 1960 SWP Convention Calls For Political Challenge To Big Business Parties By M urry Weiss The Socialist Workers Party concluded its Eighteenth National Convention last week after three days of inten sive work in an atmosphere charged with self-confident realism and revolutionary social- ist optimism. The participation election which the resolution of some 250 delegates and visi characterized "as the next major tors from every branch in the political action" facing the country marked a high point for American socialist movement. the party since the 1946 Chicago While some intensification of Convention on the eve of the the class struggle as a result of cold-war and witch-hunt period. the capitalist offensive against the living standards of the work NAACP Delegates Face Among the delegates was a large representation of youth ers is to be expected, Dobbs held that “we cannot bank on along with founders of the American communist movement, any immediate change in the veterans of the trade-union mass movement” in 1959 in time movement and front-line fight to make a labor party develop m ent in 1960 a practical possibility ers in the Negro struggle. Thus, . the vitality and continuity of Thus the urgent task in the the Marxist movement in the presidential elections is to in Crucial Policy Questions United States was personified in tensify propaganda for indepen the convention by socialists dent political action as an al whose records go back to the ternative to continued support IWW, the pre-1917 Socialist At the Soviet Fair of the Democratic Party. -

Call out Miutia in Pennsy Strike Pledges Continue To

VOL. U L, NO. 256. Philaddphia Strikere Picket Hosiery Mills PLEDGES CONTINUE CALL OUT MIUTIA n m F A T A L IN PENNSY STRIKE TO COME IN FROM TO H0]D DRIVER ALL OVER NATION Martial Law to Be Pro- ARREST THIRD MAN Yondi ffit by (^r Dmeu by daoM d ia Fayette Connty IN SYLLA MURDER RockriDe Wonian Tester- M EHCAN BEATEN Officials Busy Explaining ?A ere 15,000 Miners day Passes Away at Hos BY SrA M SB COPS Various Pbases ef die Have Defied Authorities. Stanley Kenefic Also Comes pital This Momiug. Program— Coal and Ante* from Stamford — Police Raymond Judd Stoutnar, 17, son Pl^debpbia Man (Sves Ifis mobiles Next to Be Taken lUrrlsburf, Pa., July 29—(AP)— of Mr. and Mrs. John Stoatnar of Governor Plnchot told early today Seek Fourth Suspect. 851 Tolland Turnpike died at 7:30 m Up— Monday Sled h r jna-tlal law will be proclaimed in Side of His Arrest this morning at the Manchester Me Fayette county, heart of the turbu strike there. morial hospital from injuries re dnstry WiD Disenss Code. lent coal strike area, with the ar New York, July 29.—(AP)— A Barcelona. ceived early yesterday afternoon rival of National Guard troops now third man from Stamford, Conn., enroute. when thrown from his bicycle when Three hundred state soldiers, was booked on a homicide charge to MAY REQUEST LOAN hit by an automobile driven by Mrs. New York, July 29—(AP) — The Washington, July 29.—(AP)— eoulpped with automatic rifles, day In the slaying of Dr. -

The Counter-Aesthetics of Republican Prison Writing

Notes Chapter One Introduction: Taoibh Amuigh agus Faoi Ghlas: The Counter-aesthetics of Republican Prison Writing 1. Gerry Adams, “The Fire,” Cage Eleven (Dingle: Brandon, 1990) 37. 2. Ibid., 46. 3. Pat Magee, Gangsters or Guerillas? (Belfast: Beyond the Pale, 2001) v. 4. David Pierce, ed., Introduction, Irish Writing in the Twentieth Century: A Reader (Cork: Cork University Press, 2000) xl. 5. Ibid. 6. Shiela Roberts, “South African Prison Literature,” Ariel 16.2 (Apr. 1985): 61. 7. Michel Foucault, “Power and Strategies,” Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977, ed. Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon, 1980) 141–2. 8. In “The Eye of Power,” for instance, Foucault argues, “The tendency of Bentham’s thought [in designing prisons such as the famed Panopticon] is archaic in the importance it gives to the gaze.” In Power/ Knowledge 160. 9. Breyten Breytenbach, The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1983) 147. 10. Ioan Davies, Writers in Prison (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1990) 4. 11. Ibid. 12. William Wordsworth, “Preface to Lyrical Ballads,” The Norton Anthology of English Literature vol. 2A, 7th edition, ed. M. H. Abrams et al. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2000) 250. 13. Gerry Adams, “Inside Story,” Republican News 16 Aug. 1975: 6. 14. Gerry Adams, “Cage Eleven,” Cage Eleven (Dingle: Brandon, 1990) 20. 15. Wordsworth, “Preface” 249. 16. Ibid., 250. 17. Ibid. 18. Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1990) 27. 19. W. B. Yeats, Essays and Introductions (New York: Macmillan, 1961) 521–2. 20. Bobby Sands, One Day in My Life (Dublin and Cork: Mercier, 1983) 98. -

Irish History Links

Irish History topics pulled together by Dan Callaghan NC AOH Historian in 2014 Athenry Castle; http://www.irelandseye.com/aarticles/travel/attractions/castles/Galway/athenry.shtm Brehon Laws of Ireland; http://www.libraryireland.com/Brehon-Laws/Contents.php February 1, in ancient Celtic times, it was the beginning of Spring and later became the feast day for St. Bridget; http://www.chalicecentre.net/imbolc.htm May 1, Begins the Celtic celebration of Beltane, May Day; http://wicca.com/celtic/akasha/beltane.htm. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ February 14, 269, St. Valentine, buried in Dublin; http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/irhismys/valentine.htm March 17, 461, St. Patrick dies, many different reports as to the actual date exist; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11554a.htm Dec. 7, 521, St. Columcille is born, http://prayerfoundation.org/favoritemonks/favorite_monks_columcille_columba.htm January 23, 540 A.D., St. Ciarán, started Clonmacnoise Monastery; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04065a.htm May 16, 578, Feast Day of St. Brendan; http://parish.saintbrendan.org/church/story.php June 9th, 597, St. Columcille, dies at Iona; http://www.irishcultureandcustoms.com/ASaints/Columcille.html Nov. 23, 615, Irish born St. Columbanus dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/04137a.htm July 8, 689, St. Killian is put to death; http://allsaintsbrookline.org/celtic_saints/killian.html October 13, 1012, Irish Monk and Bishop St. Colman dies; http://www.stcolman.com/ Nov. 14, 1180, first Irish born Bishop of Dublin, St. Laurence O'Toole, dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/09091b.htm June 7, 1584, Arch Bishop Dermot O'Hurley is hung by the British for being Catholic; http://www.exclassics.com/foxe/dermot.htm 1600 Sept. -

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

Dziadok Mikalai 1'St Year Student

EUROPEAN HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY Program «World Politics and economics» Dziadok Mikalai 1'st year student Essay Written assignment Course «International relations and governances» Course instructor Andrey Stiapanau Vilnius, 2016 The Troubles (Northern Ireland conflict 1969-1998) Plan Introduction 1. General outline of a conflict. 2. Approach, theory, level of analysis (providing framework). Providing the hypothesis 3. Major actors involved, definition of their priorities, preferences and interests. 4. Origins of the conflict (historical perspective), major actions timeline 5. Models of conflicts, explanations of its reasons 6. Proving the hypothesis 7. Conclusion Bibliography Introduction Northern Ireland conflict, called “the Troubles” was the most durable conflict in the Europe since WW2. Before War in Donbass (2014-present), which lead to 9,371 death up to June 3, 20161 it also can be called the bloodiest conflict, but unfortunately The Donbass War snatched from The Troubles “the victory palm” of this dreadful competition. The importance of this issue, however, is still essential and vital because of challenges Europe experience now. Both proxy war on Donbass and recent terrorist attacks had strained significantly the political atmosphere in Europe, showing that Europe is not safe anymore. In this conditions, it is necessary for us to try to assume, how far this insecurity and tensions might go and will the circumstances and the challenges of a international relations ignite the conflict in Northern Ireland again. It also makes sense for us to recognize that the Troubles was also a proxy war to a certain degree 23 Sources, used in this essay are mostly mass-media articles, human rights observers’ and international organizations reports, and surveys made by political scientists on this issue. -

Hattori Hachi.’ My Favourite Books

Praise for ‘A great debut novel.’ The Sun ‘Hattie is joined on her terrifying adventures by some fantastic characters, you can’t help but want to be one of them by the end – or maybe you’re brave enough to want to be Hattie herself . .’ Chicklish ‘Hachi is strong, independent, clever and remarkable in every way . I can’t shout loud enough about Hattori Hachi.’ My Favourite Books ‘Jane Prowse has completely nailed this novel. I loved the descriptions, the action, the heart-stopping moments where deceit lurks just around the corner. The story is fabulous, while almost hidden profoundness is scattered in every chapter.’ Flamingnet reviewer, age 12 ‘Hattori Hachi is like the female Jackie Chan, she has all the ninjutsu skills and all the moves! The Revenge of Praying Mantis is one of my all time favourite books! I love the fact that both boys and girls can enjoy it.’ Jessica, age 12 ‘I couldn’t put this book down – it was absolutely brilliant!’ Hugo, age 9 ‘This delightful book is full of ninja action and packed with clever surprises that will hook anyone who reads it!’ Hollymay, age 15 ‘This was the best book I’ve ever read. It was exciting and thrilling and when I started reading it, I could not put it back down.’ Roshane, age 18 ‘Amazing! Couldn’t put it down. Bought from my school after the author’s talk and finished it on the very next day! Jack, age 12 This edition published by Silver Fox Productions Ltd, 2012 www.silverfoxproductions.co.uk First published in Great Britain in 2009 by Piccadilly Press Ltd. -

Derry Journal – “I Can Still See Mickey Devine Laying There”

‘I can still see Mickey Devine laying thereʼ - Derry Journal 12/22/18, 1216 AM Jobs Cars Homes Directory Announcements Advertise My Business Register Login News Transport Crime Education Business Politics Environment Health More Fly New York to Toronto Ad closedFly by Toronto to New York We'll tryAd not closed to show by that ad again Round Trip $172.48 BOOKStop NOW seeing thisRound ad TripWhy$157.94 this ad? BOOK NOW ‘I can still see Mickey Devine laying there’ Share this article Published: 11:38 Our site uses cookies so that we can remember you, understand how you use our site and serve you relevant adverts and Friday 15 April 2011 content. Click the OK button, to accept cookies on this website. You can change the Cookie Settings by using the link at the bottom of the page. To !nd out more about cookies visit our Privacy & Cookies Policy. In 1981 Theresa Moore dreaded the sound of bangingOK bin lids because she knew it meant another hunger https://www.derryjournal.com/news/i-can-still-see-mickey-devine-laying-there-1-2596417 Page 1 of 10 ‘I can still see Mickey Devine laying thereʼ - Derry Journal 12/22/18, 1216 AM striker had died. Having grown up in a strong republican family in Derry, the sound of banging bin lids - a traditional sign that houses were to be raided by the RUC and British army - was nothing new to Mrs Moore, but by 1981 it had taken on a new signi!cance. At that time, the Derry woman was heavily involved in campaigning for the rights and welfare of republican prisoners. -

Critical Engagement: Irish Republicanism, Memory Politics

Critical Engagement Critical Engagement Irish republicanism, memory politics and policing Kevin Hearty LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS First published 2017 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2017 Kevin Hearty The right of Kevin Hearty to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data A British Library CIP record is available print ISBN 978-1-78694-047-6 epdf ISBN 978-1-78694-828-1 Typeset by Carnegie Book Production, Lancaster Contents Acknowledgements vii List of Figures and Tables x List of Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 1 Understanding a Fraught Historical Relationship 25 2 Irish Republican Memory as Counter-Memory 55 3 Ideology and Policing 87 4 The Patriot Dead 121 5 Transition, ‘Never Again’ and ‘Moving On’ 149 6 The PSNI and ‘Community Policing’ 183 7 The PSNI and ‘Political Policing’ 217 Conclusion 249 References 263 Index 303 Acknowledgements Acknowledgements This book has evolved from my PhD thesis that was undertaken at the Transitional Justice Institute, University of Ulster (TJI). When I moved to the University of Warwick in early 2015 as a post-doc, my plans to develop the book came with me too. It represents the culmination of approximately five years of research, reading and (re)writing, during which I often found the mere thought of re-reading some of my work again nauseating; yet, with the encour- agement of many others, I persevered. -

Bridie O'byrne

INTERVIEWS We moved then from Castletown Cross to Dundalk. My father was on the Fire Brigade in Dundalk and we had to move into town and we Bridie went to the firemen’s houses in Market Street. Jack, my eldest brother, was in the army at the time and as my father grew older Jack O’Byrne eventually left the army. He got my father’s job in the Council driving on the fire brigade and nee Rooney, steamroller and things. boRn Roscommon, 1919 Then unfortunately in 1975 a bomb exploded in ’m Bridie O’Byrne - nee Crowes Street (Dundalk). I was working in the Echo at the time and I was outside the Jockeys Rooney. I was born in (pub) in Anne Street where 14 of us were going Glenmore, Castletown, out for a Christmas drink. It was about five minutes to six and the bomb went off. At that in Roscommon 90 time I didn’t know my brother was involved in years ago 1 . My it. We went home and everyone was talking Imother was Mary Harkin about the bomb and the bomb. The following day myself and my youngest son went into town from Roscommon and my to get our shopping. We went into Kiernan’s first father was Patrick Rooney to order the turkey and a man there asked me from Glenmore. I had two how my brother was and, Lord have mercy on Jack, he had been sick so I said, “Oh he’s grand. “Did you brothers Jack and Tom and He’s back to working again.” And then I got to not know my sister Molly; just four of White’s in Park Street and a woman there asked me about my brother and I said to her, “Which that your us in the family. -

Leading to Peace: Prisoner Resistance and Leadership Development in the IRA and Sinn Fein

Leading to Peace: Prisoner Resistance and Leadership Development in the IRA and Sinn Fein By Claire Delisle Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Ph.D. degree in Criminology Department of Criminology Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa ©Claire Delisle, Ottawa, Canada, 2012 To the women in my family Dorothy, Rollande, Émilie, Phoebe and Avril Abstract The Irish peace process is heralded as a success among insurgencies that attempt transitions toward peaceful resolution of conflict. After thirty years of armed struggle, pitting Irish republicans against their loyalist counterparts and the British State, the North of Ireland has a reconfigured political landscape with a consociational governing body where power is shared among several parties that hold divergent political objectives. The Irish Republican Movement, whose main components are the Provisional Irish Republican Army, a covert guerilla armed organization, and Sinn Fein, the political party of Irish republicans, initiated peace that led to all-inclusive talks in the 1990s and that culminated in the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in April 1998, setting out the parameters for a non-violent way forward. Given the traditional intransigence of the IRA to consider any route other than armed conflict, how did the leadership of the Irish Republican Movement secure the support of a majority of republicans for a peace initiative that has held now for more than fifteen years? This dissertation explores the dynamics of leadership in this group, and in particular, focuses on the prisoner resistance waged by its incarcerated activists and volunteers. -

Belfast's Sites of Conflict and Structural Violence

Belfast’s Sites of Conflict and Structural Violence: An Exploration of the Transformation of Public Spaces through Theatre and Performance Sadie Gilker A Thesis in The School of Graduate Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Individualized Program) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada December 2020 © Sadie Gilker, 2020 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Sadie Gilker Entitled: Belfast’s Sites of Conflict and Structural Violence: An Exploration of the Transformation of Public Spaces through Theatre and Performance and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Individualized Program complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. Rachel Berger Examiner Thesis Supervisor(s) Dr. Emer O’Toole Thesis Supervisor(s) Dr. Gavin Foster Thesis Supervisor(s) Dr. Shauna Janssen Approved by Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director Dr. Rachel Berger Dr. Effrosyni Diamantoudi Dean iii Abstract Belfast’s Sites of Conflict and Structural Violence: An Exploration of the Transformation of Public Spaces through Theatre and Performance Sadie Gilker, MA Concordia University, 2020 This interdisciplinary project examines contemporary, everyday, and theatrical performances that represent violence in public space in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Utilizing the fields of Performance Studies, Urban Planning, and History, my thesis explores how theatre and performance can process violence and change perceptions of sites of conflict related to the Northern Irish Troubles (1968-1998). I examine Charabanc Theatre Company’s Somewhere Over the Balcony (1987), Tinderbox Theatre Company’s Convictions (2000), and Black Taxi Tours (2019) to address different time frames in Northern Ireland’s history and assess how performance interacts with violence and public space.