Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

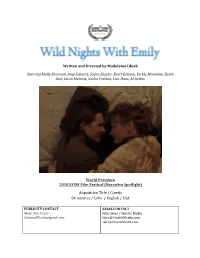

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek Starring Molly Shannon, Amy Seimetz, Susan Ziegler, Brett Gelman, Jackie Monahan, Kevin Seal, Dana Melanie, Sasha Frolova, Lisa Haas, Al Sutton World Premiere 2018 SXSW Film Festival (Narrative Spotlight) Acquisition Title / Cinetic 84 minutes / Color / English / USA PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES CONTACT Mary Ann Curto John Sloss / Cinetic Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FILM PRESS MATERIALS CONTACT and FILM CONTACT: Email: [email protected] DOWNLOAD FILM STILLS ON DROPBOX/GOOGLE DRIVE: For hi-res press stills, contact [email protected] and you will be added to the Dropbox/Google folder. Put “Wild Nights with Emily Still Request” in the subject line. The OFFICIAL WEBSITE: http://wildnightswithemily.com/ For news and updates, click 'LIKE' on our FACEBOOK page: https://www.facebook.com/wildnightswithemily/ "Hilarious...an undeniably compelling romance. " —INDIEWIRE "As entertaining and thought-provoking as Dickinson’s poetry.” —THE AUSTIN CHRONICLE SYNOPSIS THE STORY SHORT SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in " Wild Nights With Emily," a dramatic comedy. The film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman. LONG SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in the dramatic comedy " Wild Nights with Emily." The poet’s persona, popularized since her death, became that of a reclusive spinster – a delicate wallflower, too sensitive for this world. This film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (Susan Ziegler). After Emily died, a rivalry emerged when her brother's mistress (Amy Seimetz) along with editor T.W. -

Nysba Spring 2020 | Vol

NYSBA SPRING 2020 | VOL. 31 | NO. 2 Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal A publication of the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section of the New York State Bar Association In This Issue n A Case of “Creative Destruction”: Takeaways from the 5Pointz Graffiti Dispute n The American Actress, the English Duchess, and the Privacy Litigation n The Battle Against the Bots: The Legislative Fight Against Ticket Bots ....and more www.nysba.org/EASL NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION In The Arena: A Sports Law Handbook Co-sponsored by the New York State Bar Association and the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section As the world of professional athletics has become more competitive and the issues more complex, so has the need for more reliable representation in the field of sports law. Written by dozens of sports law attorneys and medical professionals, In the Arena: A Sports Law Handbook is a reflection of the multiple issues that face athletes and the attorneys who represent them. Included in this book are chapters on representing professional athletes, NCAA enforcement, advertising, sponsorship, intellectual property rights, doping, concussion-related issues, Title IX and dozens of useful appendices. Table of Contents Intellectual Property Rights and Endorsement Agreements How Trademark Protection Intersects with the Athlete’s EDITORS Right of Publicity Elissa D. Hecker, Esq. Collective Bargaining in the Big Three David Krell, Esq. Agency Law Sports, Torts and Criminal Law PRODUCT INFO AND PRICES 2013 | 539 pages Role of Advertising and Sponsorship in the Business of Sports PN: 4002 (Print) Doping in Sport: A Historical and Current Perspective PN: 4002E (E-Book) Athlete Concussion-Related Issues Non-Members $80 Concussions—From a Neuropsychological and Medical Perspective NYSBA Members $65 In-Arena Giveaways: Sweepstakes Law Basics and Compliance Issues Order multiple titles to take advantage of our low flat Navigating the NCAA Enforcement Process rate shipping charge of $5.95 per order, regardless of the number of items shipped. -

'James Cameron's Story of Science Fiction' – a Love Letter to the Genre

2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad April 27 - May 3, 2018 A S E K C I L S A M M E L I D 2 x 3" ad D P Y J U S P E T D A B K X W Your Key V Q X P T Q B C O E I D A S H To Buying I T H E N S O N J F N G Y M O 2 x 3.5" ad C E K O U V D E L A H K O G Y and Selling! E H F P H M G P D B E Q I R P S U D L R S K O C S K F J D L F L H E B E R L T W K T X Z S Z M D C V A T A U B G M R V T E W R I B T R D C H I E M L A Q O D L E F Q U B M U I O P N N R E N W B N L N A Y J Q G A W D R U F C J T S J B R X L Z C U B A N G R S A P N E I O Y B K V X S Z H Y D Z V R S W A “A Little Help With Carol Burnett” on Netflix Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) (Carol) Burnett (DJ) Khaled Adults Place your classified ‘James Cameron’s Story Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 (Taraji P.) Henson (Steve) Sauer (Personal) Dilemmas ad in the Waxahachie Daily Merchandise High-End (Mark) Cuban (Much-Honored) Star Advice 2 x 3" ad Light, Midlothian1 x Mirror 4" ad and Deal Merchandise (Wanda) Sykes (Everyday) People Adorable Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search (Lisa) Kudrow (Mouths of) Babes (Real) Kids of Science Fiction’ – A love letter Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item © Zap2it priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 to the genre for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily2 x Light,3.5" ad “AMC Visionaries: James Cameron’s Story of Science Fiction,” Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading Post premieres Monday on AMC. -

The Musical Number and the Sitcom

ECHO: a music-centered journal www.echo.ucla.edu Volume 5 Issue 1 (Spring 2003) It May Look Like a Living Room…: The Musical Number and the Sitcom By Robin Stilwell Georgetown University 1. They are images firmly established in the common television consciousness of most Americans: Lucy and Ethel stuffing chocolates in their mouths and clothing as they fall hopelessly behind at a confectionary conveyor belt, a sunburned Lucy trying to model a tweed suit, Lucy getting soused on Vitameatavegemin on live television—classic slapstick moments. But what was I Love Lucy about? It was about Lucy trying to “get in the show,” meaning her husband’s nightclub act in the first instance, and, in a pinch, anything else even remotely resembling show business. In The Dick Van Dyke Show, Rob Petrie is also in show business, and though his wife, Laura, shows no real desire to “get in the show,” Mary Tyler Moore is given ample opportunity to display her not-insignificant talent for singing and dancing—as are the other cast members—usually in the Petries’ living room. The idealized family home is transformed into, or rather revealed to be, a space of display and performance. 2. These shows, two of the most enduring situation comedies (“sitcoms”) in American television history, feature musical numbers in many episodes. The musical number in television situation comedy is a perhaps surprisingly prevalent phenomenon. In her introduction to genre studies, Jane Feuer uses the example of Indians in Westerns as the sort of surface element that might belong to a genre, even though not every example of the genre might exhibit that element: not every Western has Indians, but Indians are still paradigmatic of the genre (Feuer, “Genre Study” 139). -

PARTNERS in Hope and Discovery Where the Power of Childhood Meets the Power of Research

PARTNERS in Hope and Discovery Where the power of childhood meets the power of research 2016 ANNUAL REPORT WHERE BREAKTHROUGHS HAPPEN The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the world’s premier biomedical research institution—and the breakthroughs that happen here are the first steps toward eradicating diseases, easing pain, and making better lives possible. None Inn residents of these medical advances would be participated possible without the people who drive them: children, families and caregivers, in 283 clinicians and staff—the community The CLINICAL Children’s Inn brings together. The Inn TRIALS provides relief, support, and strength to at the NIH these pioneers whose participation in in FY16 medical trials at the NIH can change the story for children around the world. Inn residents are a part of pediatric protocols in 15 of the 27 INSTITUTES and CENTERS at the NIH On the cover: Inn resident Reem, age 7 from Egypt, with her NIH physician, Dr. Neal Young. She is being treated for aplastic anemia at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. As partners in discovery and care, OUR VISION we strive for the day when no family endures the heartbreak of a seriously ill child. Letter from the Chair of the Board and Chief Executive Officer The Inn’s Board of Directors had an eventful We are so grateful to you: our donors, volunteers, year. We have worked diligently to restructure and friends, who help The Children’s Inn make a and prepare The Inn for the future, and recently profound impact on the lives of the NIH’s young- welcomed some talented new members to our est patients. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

Turns to Affect in Feminist Film Theory 97 Anu Koivunen Sound and Feminist Modernity in Black Women’S Film Narratives 111 Geetha Ramanathan

European Film Studies Mutations and Appropriations in THE KEY DEBATES FEMINISMS Laura Mulvey and 5 Anna Backman Rogers (eds.) Amsterdam University Press Feminisms The Key Debates Mutations and Appropriations in European Film Studies Series Editors Ian Christie, Dominique Chateau, Annie van den Oever Feminisms Diversity, Difference, and Multiplicity in Contemporary Film Cultures Edited by Laura Mulvey and Anna Backman Rogers Amsterdam University Press The publication of this book is made possible by grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). Cover design: Neon, design and communications | Sabine Mannel Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 676 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 363 4 doi 10.5117/9789089646767 nur 670 © L. Mulvey, A. Backman Rogers / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2015 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents Editorial 9 Preface 10 Acknowledgments 15 Introduction: 1970s Feminist Film Theory and the Obsolescent Object 17 Laura Mulvey PART I New Perspectives: Images and the Female Body Disconnected Heroines, Icy Intelligence: Reframing Feminism(s) -

Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2017 On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era Amanda Kay Martin University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Amanda Kay, "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/ Colbert Era. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4759 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Amanda Kay Martin entitled "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Communication and Information. Barbara Kaye, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mark Harmon, Amber Roessner Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Amanda Kay Martin May 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Amanda Kay Martin All rights reserved. -

Press Release Preview

EDITOR’S NOTE: Hallmark Channel has Breaking News, go to www.crownmediapress.com for more information. TWITTER: @HallmarkChannel, @MarthaMoonWater, @Eric_Mabius, @kristintbooth, @RealCrystalLowe, @geoffgustafson, @valerieharper, @TheRealMarilu, @wolfiesmom, @SSD_TV, #POstables FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 14, 2014 Contact: Pam Slay, 818-755-2480 [email protected] EMMY® AND GOLDEN GLOBE® WINNER CAROL BURNETT CAST AS SPECIAL GUEST STAR ON SEASON ONE FINALE OF ‘SIGNED, SEALED, DELIVERED’ HALLMARK CHANNEL’S NEW ORIGINAL PRIMETIME SERIES FROM MARTHA WILLIAMSON, THE EXECUTIVE PRODUCER OF 'TOUCHED BY AN ANGEL' Series Stars Eric Mabius, Kristin Booth, Crystal Lowe and Geoff Gustafson Hallmark Channel is proud to announce award winning actress Carol Burnett (“The Carol Burnett Show”), one of America’s most beloved and respected comediennes, has signed on as a special guest star on the highly-anticipated Season One Finale of “Signed, Sealed, Delivered,” Hallmark Channel’s new Original Primetime Series. The series, which premieres Sunday, April 20, 2014 (8 p.m. ET/PT, 7C), stars Eric Mabius (“Ugly Betty”), Kristin Booth (“The Kennedys”), Crystal Lowe (“Smallville”) and Geoff Gustafson (“Primeval: New World”) and is Created and Executive Produced by Martha Williamson, best known as the Executive Producer behind the mega-hit “Touched By An Angel.” Williamson and Burnett, who did a star turn on “Touched By An Angel,” will be reunited for the first time since the series. In “Signed, Sealed, Delivered,” Ms. Burnett will guest star as the grandmother of irrepressible #POstable “Norman Dorman (Gustafson),” a core member of the quartet of untraditional mail detectives. “I never cease to be amazed by the depth of Martha Williamson's relationships in this business, as evidenced by her ability to invite one of the all-time Queens of Comedy, Carol Burnett, to be a special guest star on ‘Signed, Sealed, Delivered,’ said Michelle Vicary, Executive Vice President, Programming, Hallmark Channel and Hallmark Movie Channel. -

PDF Download Judy Garlands Judy at Carnegie Hall Kindle

JUDY GARLANDS JUDY AT CARNEGIE HALL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Manuel Betancourt | 144 pages | 14 May 2020 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781501355103 | English | New York, United States Judy Garlands Judy at Carnegie Hall PDF Book Two of her classmates in school were Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland. In fact when you see there are tributes to a band that never existed The Rutles and The Muppet Show you could argue this one has run its course Her father was a butcher. Actor Psycho. Actor Alexis Zorbas. The following year, he played the lead character in the first Mickey McGuire short film. Minimal wear on the exterior of item. Self Great Performances. Learn More - opens in a new window or tab Any international shipping and import charges are paid in part to Pitney Bowes Inc. Actress The Shining. Carol Channing was born January 31, , at Seattle, Washington, the daughter of a prominent newspaper editor, who was very active in the Christian Science movement. He was married to Thomas Kirdahy. Marilyn Monroe was an American actress, comedienne, singer, and model. Actor Pillow Talk. Alone Together. Romantic Sad Sentimental. He first took the stage as a toddler in his parents vaudeville act at 17 months old. Moving to the center of the stage, she sings with emotion as her gloved hand paints the air above her head. He made his first film appearance in Tell Your Friends Share this list:. Kay Thompson Soundtrack Funny Face Sleek, effervescent, gregarious and indefatigable only begins to describe the indescribable Kay Thompson -- a one-of-a-kind author, pianist, actress, comedienne, singer, composer, coach, dancer, choreographer, clothing designer, and arguably one of entertainment's most unique and charismatic Dropped out of high school at the age of fifteen My Profile. -

America's Closet Door: an Investigation of Television and Its Effects on Perceptions of Homosexuality

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga UTC Scholar Student Research, Creative Works, and Honors Theses Publications 12-2014 America's closet door: an investigation of television and its effects on perceptions of homosexuality Sara Moroni University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Moroni, Sara, "America's closet door: an investigation of television and its effects on perceptions of homosexuality" (2014). Honors Theses. This Theses is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. America’s Closet Door An Investigation of Television and Its Effects on Perceptions of Homosexuality Sara Moroni Departmental Thesis The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga English Project Director: Rebecca Jones, PhD. 31 October 2014 Christopher Stuart, PhD. Heather Palmer, PhD. Joanie Sompayrac, J.D., M. Acc. Signatures: ______________________________________________ Project Director ______________________________________________ Department Examiner ____________________________________________ Department Examiner ____________________________________________ Liaison, Departmental Honors Committee ____________________________________________ Chair, Departmental Honors Committee 2 Preface The 2013 “American Time Use Survey” conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics calculated that, “watching TV was the leisure activity that occupied the most time…, accounting for more than half of leisure time” for Americans 15 years old and over. Of the 647 actors that are series regulars on the five television broadcast networks (ABC, CBS, The CW, Fox, and NBC) 2.9% were LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender) in the 2011-2012 season (GLAAD). -

Sykes, Wanda (B. 1964) by Linda Rapp

Sykes, Wanda (b. 1964) by Linda Rapp Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2009 glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com A stand-up comedian who has never been shy about addressing sensitive or controversial issues on stage, Wanda Sykes has also become a spirited advocate for Wanda Sykes in 2004. glbtq rights. Image appears under the Creative Commons The daughter of an Army colonel, Wanda Sykes was born March 7, 1964 in Portsmouth, Attribution 2.5 Generic Virginia and grew up in the Maryland suburbs of Washington, D.C. while her father was license. Photograph by assigned to the Pentagon and her mother worked in banking. Wikimedia Commons contributor Nightscream. Upon graduating from Arundel High School in 1982, Sykes continued her education at Hampton University, a historically black institution in Hampton, Virginia, and earned a degree in marketing there in 1986. She immediately secured a job as a procurement officer for the National Security Agency (NSA) but quickly realized that her career did not lie in a government office. In 1987 she went on stage for the first time, doing a stand-up routine in a talent contest in Washington. Although she did not win, "a light went on" and she saw her destiny. That her second outing was a complete failure made her understand that pursuing a career in entertainment would be challenging, but, she stated, "It gave me a sense of how much I wanted to do it." While developing her skills at stand-up on nights and weekends, Sykes retained her job at the NSA until 1992, when she moved to New York to work on the comedy circuit there.