Empathy and the Female Gaze

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

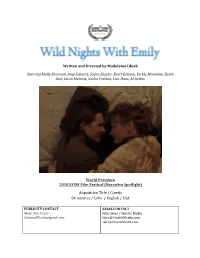

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek Starring Molly Shannon, Amy Seimetz, Susan Ziegler, Brett Gelman, Jackie Monahan, Kevin Seal, Dana Melanie, Sasha Frolova, Lisa Haas, Al Sutton World Premiere 2018 SXSW Film Festival (Narrative Spotlight) Acquisition Title / Cinetic 84 minutes / Color / English / USA PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES CONTACT Mary Ann Curto John Sloss / Cinetic Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FILM PRESS MATERIALS CONTACT and FILM CONTACT: Email: [email protected] DOWNLOAD FILM STILLS ON DROPBOX/GOOGLE DRIVE: For hi-res press stills, contact [email protected] and you will be added to the Dropbox/Google folder. Put “Wild Nights with Emily Still Request” in the subject line. The OFFICIAL WEBSITE: http://wildnightswithemily.com/ For news and updates, click 'LIKE' on our FACEBOOK page: https://www.facebook.com/wildnightswithemily/ "Hilarious...an undeniably compelling romance. " —INDIEWIRE "As entertaining and thought-provoking as Dickinson’s poetry.” —THE AUSTIN CHRONICLE SYNOPSIS THE STORY SHORT SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in " Wild Nights With Emily," a dramatic comedy. The film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman. LONG SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in the dramatic comedy " Wild Nights with Emily." The poet’s persona, popularized since her death, became that of a reclusive spinster – a delicate wallflower, too sensitive for this world. This film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (Susan Ziegler). After Emily died, a rivalry emerged when her brother's mistress (Amy Seimetz) along with editor T.W. -

Nysba Spring 2020 | Vol

NYSBA SPRING 2020 | VOL. 31 | NO. 2 Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal A publication of the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section of the New York State Bar Association In This Issue n A Case of “Creative Destruction”: Takeaways from the 5Pointz Graffiti Dispute n The American Actress, the English Duchess, and the Privacy Litigation n The Battle Against the Bots: The Legislative Fight Against Ticket Bots ....and more www.nysba.org/EASL NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION In The Arena: A Sports Law Handbook Co-sponsored by the New York State Bar Association and the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section As the world of professional athletics has become more competitive and the issues more complex, so has the need for more reliable representation in the field of sports law. Written by dozens of sports law attorneys and medical professionals, In the Arena: A Sports Law Handbook is a reflection of the multiple issues that face athletes and the attorneys who represent them. Included in this book are chapters on representing professional athletes, NCAA enforcement, advertising, sponsorship, intellectual property rights, doping, concussion-related issues, Title IX and dozens of useful appendices. Table of Contents Intellectual Property Rights and Endorsement Agreements How Trademark Protection Intersects with the Athlete’s EDITORS Right of Publicity Elissa D. Hecker, Esq. Collective Bargaining in the Big Three David Krell, Esq. Agency Law Sports, Torts and Criminal Law PRODUCT INFO AND PRICES 2013 | 539 pages Role of Advertising and Sponsorship in the Business of Sports PN: 4002 (Print) Doping in Sport: A Historical and Current Perspective PN: 4002E (E-Book) Athlete Concussion-Related Issues Non-Members $80 Concussions—From a Neuropsychological and Medical Perspective NYSBA Members $65 In-Arena Giveaways: Sweepstakes Law Basics and Compliance Issues Order multiple titles to take advantage of our low flat Navigating the NCAA Enforcement Process rate shipping charge of $5.95 per order, regardless of the number of items shipped. -

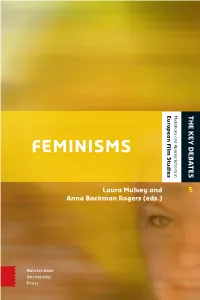

Turns to Affect in Feminist Film Theory 97 Anu Koivunen Sound and Feminist Modernity in Black Women’S Film Narratives 111 Geetha Ramanathan

European Film Studies Mutations and Appropriations in THE KEY DEBATES FEMINISMS Laura Mulvey and 5 Anna Backman Rogers (eds.) Amsterdam University Press Feminisms The Key Debates Mutations and Appropriations in European Film Studies Series Editors Ian Christie, Dominique Chateau, Annie van den Oever Feminisms Diversity, Difference, and Multiplicity in Contemporary Film Cultures Edited by Laura Mulvey and Anna Backman Rogers Amsterdam University Press The publication of this book is made possible by grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). Cover design: Neon, design and communications | Sabine Mannel Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 676 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 363 4 doi 10.5117/9789089646767 nur 670 © L. Mulvey, A. Backman Rogers / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2015 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents Editorial 9 Preface 10 Acknowledgments 15 Introduction: 1970s Feminist Film Theory and the Obsolescent Object 17 Laura Mulvey PART I New Perspectives: Images and the Female Body Disconnected Heroines, Icy Intelligence: Reframing Feminism(s) -

Shawn Paper Ace Editor

SHAWN PAPER ACE EDITOR FEATURES THE BROKEN HEARTS GALLERY Natalie Krinsky Tri-Star Pictures / No Trace Camping THAT AWKWARD MOMENT Tom Gormican Focus Features SHOULD’VE BEEN ROMEO Marc Bennett Phillybrook Films WHAT IS IT? Crispin Glover Volcanic Eruptions TELEVISION IN FROM THE COLD Ami Canaan Mann, Netflix / Silver Lining Entertainment Paco Cabezas & Birgitte Staermose SWEET TOOTH Jim Mickle, Robyn Grace Team Downey / Warner Bros Television / Netflix & Toa Fraser WHAT WE DO IN THE SHADOWS Taika Waititi, Taika Waititi, Jemaine Clement, Paul Simms / FX Official Selection, SXSW Film Festival (2019) Jemaine Clement, Jason Woliner & Jackie Van Beck CRASHING (Seasons 2 & 3) Judd Apatow, Judd Apatow, Pete Holmes, Judah Miller / HBO Gillian Robespierre, Oren Brimer & Ryan McFaul VEEP (Season 5) Various David Mandel, Julia Louis-Dreyfus / HBO Nominated, Outstanding Single-Camera Picture Editing for a Comedy Series, Primetime Emmy Awards (2012) Nominated, Best Edited Half-Hour Series for Television, ACE Eddie Awards (2012) I FEEL BAD (Pilot) Julie Anne Robinson Amy Poehler / Paper Kite Productions / NBC MOZART IN THE JUNGLE (Season 2) Paul Weitz Paul Weitz, Jason Schwartzman, Roman Coppola / Amazon GIRLS (Seasons 1, 2, 3 & 4) Richard Shepard Lena Dunham, Judd Apatow, Jenni Konner / HBO Jamie Babbit FRIENDS FROM COLLEGE Nicholas Stoller Nicholas Stoller, Francesca Delbanco / Netflix SANTA CLARITA DIET Ruben Fleischer Victor Fresco, Tracy Katsky /Netflix MARRY ME (Pilot) Seth Gordon David Caspe, Jamie Tarses / NBC GAFFIGAN (Pilot) Seth Gordon Jim -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Rebooting Roseanne: Feminist Voice Across Decades

Home > Vol 21, No 5 (2018) > Ford Rebooting Roseanne: Feminist Voice across Decades Jessica Ford In recent years, the US television landscape has been flooded with reboots, remakes, and revivals of “classic” nineties television series, such as Full/er House (1987-1995, 2016- present), Will & Grace (1998-2006, 2017-present), Roseanne (1988-1977, 2018), and Charmed (1998-2006, 2018-present). The term “reboot” is often used as a catchall for different kinds of revivals and remakes. “Remakes” are derivations or reimaginings of known properties with new characters, cast, and stories (Loock; Lavigne). “Revivals” bring back an existing property in the form of a continuation with the same cast and/or setting. “Revivals” and “remakes” both seek to capitalise on nostalgia for a specific notion of the past and access the (presumed) existing audience of the earlier series (Mittell; Rebecca Williams; Johnson). Reboots operate around two key pleasures. First, there is the pleasure of revisiting and/or reimagining characters that are “known” to audiences. Whether continuations or remakes, reboots are invested in the audience’s desire to see familiar characters. Second, there is the desire to “fix” and/or recuperate an earlier series. Some reboots, such as the Charmed remake attempt to recuperate the whiteness of the original series, whereas others such as Gilmore Girls: A Life in the Year (2017) set out to fix the ending of the original series by giving audiences a new “official” conclusion. The Roseanne reboot is invested in both these pleasures. It reunites the original cast for a short-lived, but impactful nine-episode tenth season. -

Awards Ballot.Pages

Best Screenplay Best Motion Picture - Comedy or Musical Birdman Birdman Boyhood The Grand Budapest Hotel Gone Girl Into the Woods The Grand Budapest Hotel Pride The Imitation Game St. Vincent 2015 Golden Globes ! ! Best Animated Feature Film Best Performance by an Actress in a Motion Big Hero 6 Picture - Drama FILM The Book of Life Jennifer Aniston, Cake Best Performance by an Actress The Boxtrolls Felicity Jones, The Theory of Everything in a Supporting Role How To Train Your Dragon 2 Julianne Moore, Still Alice Patricia Arquette, Boyhood The LEGO Movie Rosamund Pike, Gone Girl Jessica Chastain, A Most Violent Year ! Reese Witherspoon, Wild Keira Knightley, The Imitation Game ! Emma Stone, Birdman Best Director Best Performance by an Actor in a Motion Picture - Meryl Streep, Into the Woods Wes Anderson, The Grand Budapest Hotel Drama Ava Duvernay, Selma ! Steve Carell, Foxcatcher David Fincher, Gone Girl Best Performance by an Actress in a Motion Benedict Cumberbatch, The Imitation Game Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu, Birdman Picture - Comedy or Musical Jake Gyllenhaal, Nightcrawler Richard Linklater, Boyhood Amy Adams, Big Eyes David Oyelowo, Selma Emily Blunt, Into the Woods ! Eddie Redmayne, The Theory of Everything Helen Mirren, The Hundred-Foot Journey Best Performance by an Actor in a Motion ! Julianne Moore, Map to the Stars Picture - Comedy or Musical Best Motion Picture - Drama Quvenzhane Wallis, Annie Boyhood Ralph Fiennes, The Grand Budapest Hotel Foxcatcher ! Michael Keaton, Birdman The Imitation Game Best Performance by an Actor in a Supporting Role Bill Murray, St. Vincent Selma Robert Duvall, The Judge Joaquin Phoenix, Inherent Vice The Theory of Everything Ethan Hawke, Boyhood Christoph Waltz, Big Eyes Edward Norton, Birdman ! Mark Ruffalo, Foxcatcher ! J.K. -

Mädchen Mit Herzschmerz Elefanten Vor Gericht Brauttherapie

Mädchen mit Herzschmerz Als Hannah Horvath in „Girls“ ist sie immer wieder auch in sexuell ernie - drigenden Situationen zu sehen. In Hollywood wird Lena Dunham, 26, trotzdem als neue feministische Ikone gefeiert. Jetzt hat sich die Hauptdar - stellerin und Erfinderin der TV-Serie entschlossen, bewusster mit ihrer Vorbildfunktion als öffentliche Person umzugehen – denn da seien „all die 17-jährigen Mädchen, die zu mir kom - men und sagen, wie viel ihnen meine Serie bedeutet“. In einem Radiointer - view ließ Dunham außerdem wissen, dass sie von der Popsängerin Rihanna schwer enttäuscht sei. Die habe gegen - über ihren Anhängern verantwor - tungslos gehandelt, findet Dunham, weil Rihanna wieder mit Chris Brown zusammengekommen sei. Der Musiker hatte die Sängerin vor vier Jahren geschlagen, die Bilder ihres verletz - ten Gesichts gingen um S C die Welt. Dass Rihanna I P O T nun auch noch Fotos von R E T N sich mit ihm marihuana - I / R rauchend auf Instagram A T S G poste, sei geradezu tra - N I T O gisch. „Das bricht mir das O H S Herz“, sagte Dunham. Brauttherapie Seit der Scheidung von Brad Pitt im Jahr 2005 war Jennifer Aniston, 43, amerikanische Schauspielerin, in Begleitung diverser Männer zu beob - achten, die sich verwirrend ähnlich sa - hen. Im August vergangenen Jahres verlobte sie sich mit dem Schauspieler Justin Theroux. Damit diesmal alles gutgeht, lässt die Kalifornierin nichts unversucht: Gemeinsam mit ihrem Bräutigam in spe checkte Aniston in einer Spezialeinrichtung zur Vorberei - tung auf die Ehe ein. Drei Tage Inten - sivprogramm in Santa Monica sollten die Psyche von OLIVIER MORIN / AFP altem Ballast Elefanten vor Gericht Stunden auf schlechten Straßen durch befreien. -

AFS Year 7 Slate MASTER

AFS YEAR 7 FILM SLATE "1 AFS 2018-2019 FILM THEMES *Please note that this thematic breakdown includes documentary features, documentary shorts, animated shorts and episodic documentaries American Arts & Culture Entrepreneurism Chasing Trane! Blood, Sweat & Beer! Gentlemen of Vision! Chef Flynn! Honky Tonk Heaven: Legend of the Dealt! Broken Spoke! Ella Brennan: Commanding the Table! Jake Shimabukuro: Life on Four Strings Good Fortune! More Art Upstairs! Knife Skills! Moving Stories! New Chefs on the Block! Obit! One Hundred Thousand Beating Hearts! Restless Creature: Wendy Whelan! Human Rights Score: A Film Music Documentary! STEP! A Shot in the Dark! All-American Family! Disability Rights Bending the Arc! A Shot in the Dark! Cradle! All-American Family! Edith + Eddie! Cradle! I Am Jane Doe! Dealt! The Prosecutors! I’ll Push You! Unrest! Pick of the Litter! LGBTQI Reengineering Sam! Served Like a Girl! In A Heartbeat! Unrest! The S Word: Opening the Conversation Stumped# About Suicide! Stumped! "2 Mental Health Awareness Sports Cradle! A Shot in the Dark! Served Like a Girl! All-American Family! The S Word: Opening the Conversation Baltimore Boys! About Suicide! Born to Lead: The Sal Aunese Story! The Work! Boston: The Documentary! Unrest! Down The Fence! We Breathe Again! Run Mama Run! Skid Row Marathon! The Natural World and Space Take Every Wave: The Life of Laird A Plastic Ocean! Hamilton Above and Beyond: NASA’s Journey to STEM Tomorrow! Frans Lanting: The Evolution of Life! Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story! Mosquito! Dream Big: -

Tax Credits Issued

TAX CREDITS ISSUED TOTAL APPLICANT CREDIT PRODUCTION NAME APPLICANT ADDRESS Curious Holdings LLC dba Curious Pictures Dan Zanes Show Pilot 440 Lafayette Street, 6th floor New York, N.Y. 10003 New York New York Productions, Inc. Good Shepherd 10 East Lee Street, Suite 2705 Baltimore, MD 21202 Forever the Film LLC Never Forever 180 Varick Street, Ste. 1002 New York, N.Y. 10014 c/o Trevanna Post, Inc. 161 Avenue of the Americas, #902 New Pretty Good Productions, Inc Win Win York, N.Y. 10013 Prime Film Production, LLC Prime 10850 Wilshire Blvd.,6th floor, Los Angeles, CA. 90024 The Ten Film, LLC Ten 6 East 39th Street, New York, N.Y. 10016 Fast Lane Productions Inc, dba FILMAURO Christmas (Natale) in NY 9623 Charleville Blvd. Beverly Hills, CA 90212 Girl in the Park, LLC Girl in the Park 9242 Beverly Blvd., Suite 200 Beverly Hills, CA 90210 57th & Irving The Cake Eaters LLC Cake Eaters 19 W 21st Street, Suite 706 New York, N.Y. 10010 c/o River Road Entertainment 60 South 6th Street, Suite 4050 FURTHEFILM, LLC Fur Minneapolis, MN 55402 Freedomland Productions, Inc. Freedomland 2900 West Olympic Blvd. 2nd floor Santa Monica, CA 90404 Griffin & Phoenix Productions LLC Griffin and Phoenix 9420 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 250 Beverly Hills, CA 90212 Reason For Leaving LP Wreck, The 601 W. 26th St. Suite 1255, New York, N.Y. 10001 Eric Nadler Transbeman 10 Jay Street, #204, Brooklyn, New York 11201 Gregory Lamberson Slime City Massacre 1824 Kensington Avenue, Cheektowaga, N.Y. 14215 Whitest Kids You Know Season 4; Whitest Kids You Know Season 3; Whitest Kids You L.C Incorporated $987,780 Know Season 5 c/o GRF LLP, 360 Hamilton Ave, #100 White Plains, NY 10601 Persona Films Inc. -

The Voice of a Generation: Anexploration of Lena

THE VOICE OF A GENERATION: ANEXPLORATION OF LENA DUNHAM’S MULTI-MODAL PERSONAE by Torrey Rae Lynch A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2016 ©COPYRIGHT by Torrey Rae Lynch 2016 All Rights Reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................1 2. CHAPTER ONE: “TRUTHTELLING” WITHIN A MEMOIR-ISH: A LOOK INTO DUNHAM’S NOT THAT KIND OF GIRL: A YOUNG WOMAN TELLS YOU WHAT SHE’S “LEARNED” .............................................................................14 “Grace,” Gendered Authorship, and Narrative Geography .................................................................................................21 “Barry” and The Co-Authoring of Narratives ........................................................28 Having it All-ish ..........................................................................................................33 3. CHAPTER TWO: TOWARD A SAFER AND HOMIER SPACE: A FEMINIST CRITIQUE ON DUNHAM’S WEBSITE/E-NEWSLETTER, LENNY .....................................................................38 Third-Wave as Contradictory ...................................................................................42 Digital Sphere as Safe-ish ..........................................................................................48 Home and Not Home .................................................................................................51 -

Chronline.Com

Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com $1 Weekend Edition Saturday, Aug. 18, 2012 Local Firefighters Help Beat Back Taylor Bridge Fire / Main 4 Traveling to the Blaze A Weird Day at the Fair / Main 16 The Great Baby Race / Main 14 Joshua Trujillo / AP Photo/seattleti.com Tracy Summers of Toledo monitors the scene above Hidden Valley Ranch where ire crews worked to halt progression of the Taylor Bridge Fire on Thursday near Cle Elum. The Taylor Bridge Fire has forced hundreds to evacuate and has burned dozens of homes near Cle Elum. Good to Very the Very Fair Last Bite Southwest Washington Fair Photos Winds Down / Main 13 Check out Images From a Week at the Fairgrounds / chronline.com Life in the Minors Chehalis Athlete Plays for Minor League M’s/ Sports 1 The Chronicle, Serving The Greater Weather Eclectic Offerings Deaths Lewis County Area Since 1889 TONIGHT: Low 57 Wide Array of Music at the Fair / Main 13 Alford, Douglas, 59, Follow Us on Twitter TOMORROW: High 75 Chehalis @chronline Mostly Cloudy see details on page Main 2 Find Us on Facebook www.facebook.com/ Weather picture by Bryar thecentraliachronicle Reed, fifth grade, Onalaska Elementary School It’s BACK-TO-AWESOME HAIR TIME. Kids Cut Kids Cut Plus Backpack Drawing Fantastic Sams - Chehalis 1549 NW Louisiana Avenue, PH: Tel: 360-740-4775 ENTER TO WIN A M-Thur 10 to 8, Fri 9 to 8 $8.95 $12.95 BACKPACK AND SCHOOL SUPPLIES Sat 9 to 6, Sun 10 to 6 Professional Haircut Professional Haircut & Style Fantastic Sams - Lacey 4660 Whitman LN #D, PH: 360-493-1751 Expires 09/10/2012.