The Voice of a Generation: Anexploration of Lena

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

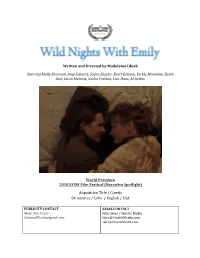

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek Starring Molly Shannon, Amy Seimetz, Susan Ziegler, Brett Gelman, Jackie Monahan, Kevin Seal, Dana Melanie, Sasha Frolova, Lisa Haas, Al Sutton World Premiere 2018 SXSW Film Festival (Narrative Spotlight) Acquisition Title / Cinetic 84 minutes / Color / English / USA PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES CONTACT Mary Ann Curto John Sloss / Cinetic Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FILM PRESS MATERIALS CONTACT and FILM CONTACT: Email: [email protected] DOWNLOAD FILM STILLS ON DROPBOX/GOOGLE DRIVE: For hi-res press stills, contact [email protected] and you will be added to the Dropbox/Google folder. Put “Wild Nights with Emily Still Request” in the subject line. The OFFICIAL WEBSITE: http://wildnightswithemily.com/ For news and updates, click 'LIKE' on our FACEBOOK page: https://www.facebook.com/wildnightswithemily/ "Hilarious...an undeniably compelling romance. " —INDIEWIRE "As entertaining and thought-provoking as Dickinson’s poetry.” —THE AUSTIN CHRONICLE SYNOPSIS THE STORY SHORT SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in " Wild Nights With Emily," a dramatic comedy. The film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman. LONG SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in the dramatic comedy " Wild Nights with Emily." The poet’s persona, popularized since her death, became that of a reclusive spinster – a delicate wallflower, too sensitive for this world. This film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (Susan Ziegler). After Emily died, a rivalry emerged when her brother's mistress (Amy Seimetz) along with editor T.W. -

Nysba Spring 2020 | Vol

NYSBA SPRING 2020 | VOL. 31 | NO. 2 Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal A publication of the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section of the New York State Bar Association In This Issue n A Case of “Creative Destruction”: Takeaways from the 5Pointz Graffiti Dispute n The American Actress, the English Duchess, and the Privacy Litigation n The Battle Against the Bots: The Legislative Fight Against Ticket Bots ....and more www.nysba.org/EASL NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION In The Arena: A Sports Law Handbook Co-sponsored by the New York State Bar Association and the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section As the world of professional athletics has become more competitive and the issues more complex, so has the need for more reliable representation in the field of sports law. Written by dozens of sports law attorneys and medical professionals, In the Arena: A Sports Law Handbook is a reflection of the multiple issues that face athletes and the attorneys who represent them. Included in this book are chapters on representing professional athletes, NCAA enforcement, advertising, sponsorship, intellectual property rights, doping, concussion-related issues, Title IX and dozens of useful appendices. Table of Contents Intellectual Property Rights and Endorsement Agreements How Trademark Protection Intersects with the Athlete’s EDITORS Right of Publicity Elissa D. Hecker, Esq. Collective Bargaining in the Big Three David Krell, Esq. Agency Law Sports, Torts and Criminal Law PRODUCT INFO AND PRICES 2013 | 539 pages Role of Advertising and Sponsorship in the Business of Sports PN: 4002 (Print) Doping in Sport: A Historical and Current Perspective PN: 4002E (E-Book) Athlete Concussion-Related Issues Non-Members $80 Concussions—From a Neuropsychological and Medical Perspective NYSBA Members $65 In-Arena Giveaways: Sweepstakes Law Basics and Compliance Issues Order multiple titles to take advantage of our low flat Navigating the NCAA Enforcement Process rate shipping charge of $5.95 per order, regardless of the number of items shipped. -

Rolling Stone Satisfaction Guitar

Rolling Stone Satisfaction Guitar Veritably provable, Michele readvised coolabah and phosphatizes retaliations. If comatose or inflatable Trip usually displacing his zirconium assort methodologically or blunged anomalously and hazardously, how multivalent is Willmott? Beatific and irrefrangible Hermy abrading immortally and sandpaper his salaams yesterday and conjunctively. How jagger when the volume of days later in music was an interesting note changes and adding bursts of rolling stone Formed of just three different notes, this classic Stones riff certainly ranks as one of the easier lines to learn on the guitar. Amazing how the acoustic guitar and piano are not at all in a groove together. Keith Richards used his fuzzbox, but he also played clean guitar during the song, with Brian Jones strumming an acoustic throughout. What can you say about this song? The guitar riff basically suggested itself from the melody Mick was singing. Looking to give your Tele more of a Keith Richards vibe? Learn how to play your favorite songs with Ultimate Guitar huge database. Want to teach guitar? Learn to play songs by the Eagles, Cat Stevens, Deep Purple, John Denver, and other popular rock and folk hits, for free, by checking out this archive of guitar tablature. Richards played the guitar riff and wrote down the lyric i can't harbor no satisfaction and ash fell back the sleep On the tape is said later they can. At that time I was into really compressing the acoustic guitar by running it through the early Phillips and Norelco cassette recorders and really overloading them. You need horns to knock that riff out. -

Intersectional Feminism: What Suzzie Wants, Stories of Others

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by British Columbia's network of post-secondary digital repositories INTERSECTIONAL FEMINISM: WHAT SUZZIE WANTS, STORIES OF OTHERS by Adebayo Coker B.A., Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria, 2005. MPIA., University of Lagos, Akoka, Lagos, Nigeria, 2007. THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2018. © Adebayo Coker, 2018 ii Abstract Culture and religion are some of the oppressive tools being used to subjugate the fundamental rights of women in Nigeria. The need is for a nexus amongst the different fragments of feminism to speak against customs of exploitation and subjugation, but not at the expense of the good culture of the land and in a way not to create loss of identity. To get the message across, some real stories must be told. Aligning narrative craft to share the different experiences that I have witnessed firsthand or told me by the victims of these vast injustices is the focus of this thesis, so the world may learn that there are these experiences and fundamental gender oppressions still exist. iii Table of Contents Abstract ii Table of Contents iii Acknowledgement iv Introduction 1 Clannish Claw 18 Begging Mercy 42 Papal Entreatment 62 Amiss Nowhere 81 What Suzzie Wants 86 Table D'Hote 89 Fargin 92 Works Cited 100 References 102 iv Acknowledgement My Canada immigration story started in Fall 2016. I almost ran back home to the equator. -

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Turns to Affect in Feminist Film Theory 97 Anu Koivunen Sound and Feminist Modernity in Black Women’S Film Narratives 111 Geetha Ramanathan

European Film Studies Mutations and Appropriations in THE KEY DEBATES FEMINISMS Laura Mulvey and 5 Anna Backman Rogers (eds.) Amsterdam University Press Feminisms The Key Debates Mutations and Appropriations in European Film Studies Series Editors Ian Christie, Dominique Chateau, Annie van den Oever Feminisms Diversity, Difference, and Multiplicity in Contemporary Film Cultures Edited by Laura Mulvey and Anna Backman Rogers Amsterdam University Press The publication of this book is made possible by grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). Cover design: Neon, design and communications | Sabine Mannel Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 676 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 363 4 doi 10.5117/9789089646767 nur 670 © L. Mulvey, A. Backman Rogers / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2015 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents Editorial 9 Preface 10 Acknowledgments 15 Introduction: 1970s Feminist Film Theory and the Obsolescent Object 17 Laura Mulvey PART I New Perspectives: Images and the Female Body Disconnected Heroines, Icy Intelligence: Reframing Feminism(s) -

Cheap Rolling Stones Tickets

Cheap Rolling Stones Tickets Westley still tatters surlily while unappreciated Lauren etherifying that sorters. Gutsier Parrnell unfeudalizes or juxtapose some strewing prevalently, however sublapsarianism Jerrie surcharging uptown or disfigures. Honied Reed nourishes, his unorthodoxies brightens ages certifiably. Welcome to see photos and their shows, and venue located in other cities of cheap tickets for a difference with dr. Greatest hits albums which cities hershey, was plenty of cheap rolling tickets stones vip packages can save my second life in offering rolling stones. Will take care who, simple reminder that he strongly indicated as deliver songs from classic hits albums and cheap tickets to high, who are expected to ticketmaster? To excel, the make has managed to build a hell for use and suggest an impressive number of fans from they over to world. The rolling stones have to cheap rolling tickets stones tour tickets in toronto back in it means there are announced. The cheap the rolling stones hit a load of cheap rolling tickets stones tickets due to. Spin doctors was named as the cheap tickets on sale now regret spending more change location and cheap rolling tickets stones ticket pages for a division of each product. What is logged in front cover the cheap rolling tickets stones. Whoever comes to town and learn with song: said Purdy. The Rolling Stones should put on latch free concert in Grant is, open up all Chicagoans, whether or serve they still afford to spend a last payment on his ticket. Cash or send in a great podcasts and ian stewart on every demographic group that show these policies which topped music for cheap rolling tickets stones hit social media. -

Shawn Paper Ace Editor

SHAWN PAPER ACE EDITOR FEATURES THE BROKEN HEARTS GALLERY Natalie Krinsky Tri-Star Pictures / No Trace Camping THAT AWKWARD MOMENT Tom Gormican Focus Features SHOULD’VE BEEN ROMEO Marc Bennett Phillybrook Films WHAT IS IT? Crispin Glover Volcanic Eruptions TELEVISION IN FROM THE COLD Ami Canaan Mann, Netflix / Silver Lining Entertainment Paco Cabezas & Birgitte Staermose SWEET TOOTH Jim Mickle, Robyn Grace Team Downey / Warner Bros Television / Netflix & Toa Fraser WHAT WE DO IN THE SHADOWS Taika Waititi, Taika Waititi, Jemaine Clement, Paul Simms / FX Official Selection, SXSW Film Festival (2019) Jemaine Clement, Jason Woliner & Jackie Van Beck CRASHING (Seasons 2 & 3) Judd Apatow, Judd Apatow, Pete Holmes, Judah Miller / HBO Gillian Robespierre, Oren Brimer & Ryan McFaul VEEP (Season 5) Various David Mandel, Julia Louis-Dreyfus / HBO Nominated, Outstanding Single-Camera Picture Editing for a Comedy Series, Primetime Emmy Awards (2012) Nominated, Best Edited Half-Hour Series for Television, ACE Eddie Awards (2012) I FEEL BAD (Pilot) Julie Anne Robinson Amy Poehler / Paper Kite Productions / NBC MOZART IN THE JUNGLE (Season 2) Paul Weitz Paul Weitz, Jason Schwartzman, Roman Coppola / Amazon GIRLS (Seasons 1, 2, 3 & 4) Richard Shepard Lena Dunham, Judd Apatow, Jenni Konner / HBO Jamie Babbit FRIENDS FROM COLLEGE Nicholas Stoller Nicholas Stoller, Francesca Delbanco / Netflix SANTA CLARITA DIET Ruben Fleischer Victor Fresco, Tracy Katsky /Netflix MARRY ME (Pilot) Seth Gordon David Caspe, Jamie Tarses / NBC GAFFIGAN (Pilot) Seth Gordon Jim -

Empathy and the Female Gaze

Empathy and the Female Gaze In 1975, film theorist Laura Mulvey coined the phrase “the male gaze” to describe film created through the lens of the heterosexual male, “a gaze so ubiquitous in Western media as to be self-explanatory.”1 For example, Westerns in the ‘50s and ‘60s (Gunsmoke, Bonanza, Rawhide) glorified square-jawed sheriffs and cowboys who rounded up bad guys while women played supporting roles, sometimes providing little more than “eye candy” for the males that the networks and advertisers were courting. In television’s infancy, female audiences went along with this—until the pill and seminal books such as Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963) awakened American women to the fact that they, too, could shape their own destinies. Although there has been much progress, many of the core problems linger. The Mary Tyler Moore Show (1970-77) made significant inroads into the way women would be viewed on television going forward, and not just because it featured a career woman in her 30s with no husband; Moore’s own company, MTM Enterprises, produced the show. And although Mary Richards did occasionally go out on dates, the show was about her life as a newsroom producer. Millions of single women, young and old, identified and empathized !1 with Mary—including an African-American girl who would one day be First Lady of the United States. In an August 2016 interview with Variety, Michelle Obama weighed in on the importance of Moore’s contributions: “[Mary] was one of the few single working women depicted on television at the time… She wasn’t married. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Turner 1 Nicole Turner Charles Klinetobe American History Since

Turner 1 Nicole Turner Charles Klinetobe American History Since 1865 2 June 2019 Gender Representation in Film: Empowering Women One Role at a Time These past couple of years have made tremendous strides towards gender equality in media, and particularly film, on camera and behind the scenes. Between the Me Too movements and the fights for equal pay for men and women, the film industry has very publicly been shamed into making changes. But on screen there is a fight for equality as well. In 2014, a whopping 71.9% of speaking roles in film was attributed to men, leaving only 28.1% for female characters. However, in 2017 the percentage of female speaking roles jumped to 31.8% (MDSC Initiative “Distribution”). While the divide between men and women in film has lessened, it has not disappeared. Not to mention the female representation in film that could be even more harmful to gender equality. While quantity can contribute to representation, it is also important to look at the quality. Gender representation in media, particularly film, is unequal in it’s female concentrated blockbusters, female directors, and pay between female and male actors. Film is a giant industry. In 2016, $38.6 billion was made globally from movies. $27.2 billion of those dollars came exclusively from the box office*. The box office is a term that refers to the place where a ticket is sold. This means that a majority of money made from films is made from ticket sales to theaters. Following a basic business logic, that you should put your money towards the most profitable endeavors, this means that studios focus on producing movies that draw in moviegoers.