The Cranberries on Losing Dolores O'riordan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fungous Diseases of the Cultivated Cranberry

:; ~lll~ I"II~ :: w 2.2 "" 1.0 ~ IW. :III. w 1.1 :Z.. :: - I ""'1.25 111111.4 IIIIII.~ 111111.25 111111.4 111111.6 MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART NArIONAl BUR[AU or STANO~RD5·J96:'.A NATiDNAL BUREAU or STANDARDS·1963.A , I ~==~~~~=~==~~= Tl!ClP'llC....L BULLl!nN No. 258 ~ OCTOBER., 1931 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE WASHINGTON, D_ C. FUNGOUS DISEASES OF THE CULTIVATED CRANBERRY By C. L. SHEAll, PrincipuJ PatholOgist in. Oharge, NELL E. STEVESS, Senior Path· olOf/i8t, Dwi8ion of MycoloYlI una Disruse [{ul-vey, and HENRY F. BAIN, Senior Putholoyist, DivisiOn. of Hortil'Ulturul. Crops ana Disea8e8, Bureau of Plant InifU8try CONTENTS Page Page 1..( Introduction _____________________ 1 PhYlllology of the rot fungl-('ontd. 'rtL~onomy ____ -' _______________ ,....~,_ 2 Cllmates of different cranberry Important rot fungL__________ 2 s('ctions in relation to abun dun~e of various fungL______ 3:; Fungi canslng diseuses of cr':ll- Relatlnn betwpen growing-~eason berry vlnrs_________________ Il weather nnd k('eplng quality of Cranberry tungl o.f minor impol'- tuncB______________________ 13 chusettsthl;' cranberry ___________________ ('rop ill :lfassa 38 Physiology of tbe T.ot fungl_____ . 24 Fungous diseuses of tIle cl'llobpl'ry Time ot infectlou _____________ 24 and their controL___ __________ 40 Vine dlseas..s_________________ 40 DlssemInntion by watl'r________ 25 Cranberry fruit rots ___________ 43 Acidity .relatlouB_____________ _ 2" ~ummary ________________________ 51 Temperature relationS _________ -

HYPE-34-Genesis.Pdf

Exclusive benefits for Students and NSFs FREE Campus/Camp Calls Unlimited SMS Incoming Calls Data Bundle Visit www.singtel.com/youth for details. Copyright © 2012 SingTel Mobile Singapore Pte. Ltd. (CRN : 201012456C) and Telecom Equipment Pte. Ltd. (CRN: 198904636G). Standard SingTel Mobile terms and conditions apply. WHERE TO FIND HYPE COMPLIMENTARY COPIES OF HYPE ARE AVAILABLE AT THE FOLLOWING PLACES Timbre @ The Arts House Island Creamery Swirl Art 1 Old Parliament Lane #01-04 11 King Albert Park #01-02 417 River Valley Road Timbre @ The Substation Serene Centre #01-03 1 Liang Seah Street #01-13/14 45 Armenian Street Holland Village Shopping Mall #01-02 Timbre @ Old School The Reckless Shop 11A Mount Sophia #01-05 Sogurt Orchard Central #02-08/09 617 Bukit Timah Road VivoCity #02-201 Cold Rock Blk 87 Marine Parade Central #01-503 24A Lorong Mambong DEPRESSION 313 Somerset #02-50 Leftfoot Orchard Cineleisure #03-05A 2 Bayfront Avenue #B1-60 Far East Plaza #04-108 Millenia Walk Parco #P2-21 Orchard Cineleisure #02-07A BooksActually The Cathay #01-19 Beer Market No. 9 Yong Siak Street, Tiong Bahru 3B River Valley Road #01-17/02-02 Once Upon a Milkshake St Games Cafe 32 Maxwell Road #01-08 Strictly Pancakes The Cathay #04-18 120 Pasir Ris Central #01-09 44A Prinsep Street Frolick Victoria Jomo Ice Cream Chefs Lot One #B1-23 9 Haji Lane Ocean Park Building, #01-06 Hougang Mall #B1-K11 47 Haji Lane 12 Jalan Kuras (Upper Thomson) 4 Kensington Park Road Tampines 1 #B1-32 VOL.TA Marble Slab 241 Holland Avenue #01-02 The Cathay #02-09 Iluma -

Concert History of the Allen County War Memorial Coliseum

Historical Concert List updated December 9, 2020 Sorted by Artist Sorted by Chronological Order .38 Special 3/27/1981 Casting Crowns 9/29/2020 .38 Special 10/5/1986 Mitchell Tenpenny 9/25/2020 .38 Special 5/17/1984 Jordan Davis 9/25/2020 .38 Special 5/16/1982 Chris Janson 9/25/2020 3 Doors Down 7/9/2003 Newsboys United 3/8/2020 4 Him 10/6/2000 Mandisa 3/8/2020 4 Him 10/26/1999 Adam Agee 3/8/2020 4 Him 12/6/1996 Crowder 2/20/2020 5th Dimension 3/10/1972 Hillsong Young & Free 2/20/2020 98 Degrees 4/4/2001 Andy Mineo 2/20/2020 98 Degrees 10/24/1999 Building 429 2/20/2020 A Day To Remember 11/14/2019 RED 2/20/2020 Aaron Carter 3/7/2002 Austin French 2/20/2020 Aaron Jeoffrey 8/13/1999 Newsong 2/20/2020 Aaron Tippin 5/5/1991 Riley Clemmons 2/20/2020 AC/DC 11/21/1990 Ballenger 2/20/2020 AC/DC 5/13/1988 Zauntee 2/20/2020 AC/DC 9/7/1986 KISS 2/16/2020 AC/DC 9/21/1980 David Lee Roth 2/16/2020 AC/DC 7/31/1979 Korn 2/4/2020 AC/DC 10/3/1978 Breaking Benjamin 2/4/2020 AC/DC 12/15/1977 Bones UK 2/4/2020 Adam Agee 3/8/2020 Five Finger Death Punch 12/9/2019 Addison Agen 2/8/2018 Three Days Grace 12/9/2019 Aerosmith 12/2/2002 Bad Wolves 12/9/2019 Aerosmith 11/23/1998 Fire From The Gods 12/9/2019 Aerosmith 5/17/1998 Chris Young 11/21/2019 Aerosmith 6/22/1993 Eli Young Band 11/21/2019 Aerosmith 5/29/1986 Matt Stell 11/21/2019 Aerosmith 10/3/1978 A Day To Remember 11/14/2019 Aerosmith 10/7/1977 I Prevail 11/14/2019 Aerosmith 5/25/1976 Beartooth 11/14/2019 Aerosmith 3/26/1975 Can't Swim 11/14/2019 After Seven 5/19/1991 Luke Bryan 10/23/2019 After The Fire -

Shinedownthe Biggest Band You've Never Heard of Rocks the Coliseum

JJ GREY & MOFRO DAFOE IS VAN GOGH LOCAL THEATER things to do 264 in the area AT THE PAVILION BRILLIANT IN FILM PRODUCTIONS CALENDARS START ON PAGE 12 Feb. 28-Mar. 6, 2019 FREE WHAT THERE IS TO DO IN FORT WAYNE AND BEYOND THE BIGGEST BAND YOU’VE NEVER SHINEDOWN HEARD OF ROCKS THE COLISEUM ALSO INSIDE: ADAM BAKER & THE HEARTACHE · CASTING CROWNS · FINDING NEVERLAND · JO KOY whatzup.com Just Announced MAY 14 JULY 12 JARED JAMES NICHOLS STATIC-X AND DEVILDRIVER GET Award-winning blues artist known for Wisconsin Death Trip 20th Anniversary energetic live shows and bombastic, Tour and Memorial Tribute to Wayne Static arena-sized rock 'n' roll NOTICED! Bands and venues: Send us your events to get free listings in our calendar! MARCH 2 MARCH 17 whatzup.com/submissions LOS LOBOS W/ JAMES AND THE DRIFTERS WHITEY MORGAN Three decades, thousands of A modern day outlaw channeling greats performances, two Grammys, and the Waylon and Merle but with attitude and global success of “La Bamba” grit all his own MARCH 23 APRIL 25 MEGA 80’S WITH CASUAL FRIDAY BONEY JAMES All your favorite hits from the 80’s and Grammy Award winning saxophonist 90’s, prizes for best dressed named one of the top Contemporary Jazz musicians by Billboard Buckethead MAY 1 Classic Deep Purple with Glenn Hughes MAY 2 Who’s Bad - Michael Jackson Tribute MAY 4 ZoSo - Led Zeppelin Tribute MAY 11 Tesla JUNE 3 Hozier: Wasteland, Baby! Tour JUNE 11 2 WHATZUP FEBRUARY 28-MARCH 6, 2019 Volume 23, Number 31 Inside This Week LIMITED-TIME OFFER Winter Therapy Detailing Package 5 Protect your vehicle against winter Spring Forward grime, and keep it looking great! 4Shinedown Festival FULL INTERIOR AND CERAMIC TOP COAT EXTERIOR DETAILING PAINT PROTECTION Keep your car looking and Offers approximately four feeling like new. -

The Songs to This Day Continue to Gain New Fans with Every Listen.”

LOGIN HOME NEWS FEATURES CHARTS NEW MUSIC EVENTS JOBS DIRECTORY 2020 ALL SECTIONS LABELS TALENT PUBLISHING LIVE DIGITAL MANAGEMENT BRANDS MEDIA SEARCH & Primary Wave acquires songwriting catalogue of Cranberries' Noel Hogan by Andre Paine January 21st 2020 at 7:27AM MUSIC WEEK JOBS Marketing Manager UK - London APPLY NOW Digital Assistant UK - London APPLY NOW A&R/Label Manager Maidstone, Kent Primary Wave has acquired a majority stake in the music publishing catalogue of Noel Hogan, co- songwriter and lead guitarist for The Cranberries, Music Week can reveal. APPLY NOW The deal includes some of the group’s biggest hits, such as Linger, Salvation, Dreams and Ode to Music Sales My Family, as well as a number of songs on the band’s final album In The End. Executive UK InIn TheThe EndEnd isis nominatednominated forfor BestBest RockRock AlbumAlbum atat thisthis year’syear’s GrammyGrammy AwardsAwards. Released APPLY NOW by BMG, the LP made the UK Top 10. Record Label “I’m delighted to join the Primary Wave family of writers,” said Hogan (pictured, far left). “It’s a great Manager honour to be in such legendary company. I look forward to many great years together.” Nottingham (or London possible) APPLY NOW The songs to this day continue to gain new fans Head of Artwork with every listen and Reprographics, Brighton UK - Brighton Justin Shukat APPLY NOW “We are ecstatic to enter into a deal with Noel Hogan,” says Justin Shukat, president of publishing for Primary Wave. “Our team and I have been big fans of The Cranberries since their VIEW ALL JOBS inception. -

LADYHAWKE: the Bullingdon Tour to Promote His Debut EP

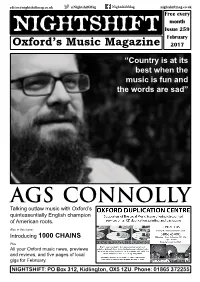

[email protected] @NightshiftMag NightshiftMag nightshiftmag.co.uk Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 259 February Oxford’s Music Magazine 2017 “Country is at its best when the music is fun and the words are sad” AGS CONNOLLY Talking outlaw music with Oxford’s quintessentially English champion of American roots. Also in this issue: Introducing 1000 CHAINS Plus All your Oxford music news, previews and reviews, and five pages of local gigs for February. NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshiftmag.co.uk played host to the likes of Willie J Healey; Duotone; Esther Joy Lane; Wolf Alice; The Fusion Project and Kioko. Visit www. sofarsounds.com/oxford to find out more. CATWEAZLE host a new series of monthly live music and spoken word events starting this month. Making A Scene takes place at The Oxford Centre for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing on the first Saturday of each month. The first event takes place on the 4th February with sets from Art Theefe, fronted by Catweazle host Matt Sage, plus Temper Cartel, Ed Pope, Steve Karlin, Xogara and TRUCK FESTIVAL will announce the Kira Millwood Hargrave, with subsequent first set of names for its 2017 line-up on events on the 4th March and 1st April. Monday 6th February. This year’s event Tickets and info from once again runs across three days, over the www.catweazleclub.com. weekend of the 21st-23rd July, at Hill Farm in Steventon. -

D.A.R.K. Bandmates Remember Dolores O'riordan

Subscribe Past Issues Translate RSS View this email in your browser January 17, 2018 D.A.R.K. Remembers Dolores O'Riordan D.A.R.K. L to R: Andy Rourke, Dolores O'Riordan, Olé Koretsky Photo credit: Jen Maler It's with overwhelming sadness that D.A.R.K. has announced the death of Dolores O'Riordan who passed away suddenly at the age of 46 in London, England on January 15, 2018. Dolores is also known for being the lead singer of successful Irish rock band the Cranberries. "I am heartbroken and devastated by the news of the sudden and unexpected passing of Dolores," said band mate and member of The Smiths Andy Rourke. "I have truly enjoyed the years we spent together and feel privileged to call her a close friend. It was a bonus to work with her in our band D.A.R.K. and witness firsthand her breathtaking and unique talent. I will miss her terribly. I send my love and condolences to her family and loved ones." Band mate and partner Olé Koretsky adds, "My friend, partner, and the love of my life is gone. My heart is broken and it is beyond repair. Dolores is beautiful. Her art is beautiful. Her family is beautiful. The energy she continues to radiate is undeniable. I am lost. I miss her so much. I will continue to stumble around this planet for some time knowing well there's no real place for me here now." Born on September 6, 1971, Dolores first rose to prominence with band The Cranberries with the release of platinum-selling debut album Everyone Else Is Doing It, So Why Can't We? in 1993 which yielded the worldwide hits "Dreams" and "Linger." With seven albums as the Cranberries, two solo albums, and one album for D.A.R.K., Dolores leaves a rich legacy and a wealth of breathtaking recordings. -

The Cranberries - All Over Now Episode 158

Song Exploder The Cranberries - All Over Now Episode 158 Thao: You’re listening to Song Exploder, where musicians take apart their songs and piece by piece tell the story of how they were made. My name is Thao Nguyen. (“All Over Now” by THE CRANBERRIES) Thao: The Cranberries formed in Limerick, Ireland in 1989. Singer Dolores O’Riordan joined a year later, and the group went on to become one of the defining bands of the ‘90s, eventually selling over 40 million records worldwide. In January 2018, while the band was working on their eighth album, Dolores O’Riordan passed away unexpectedly. Later that year, remaining members Noel Hogan, Mike Hogan, and Fergal Lawler announced that they would end the band, and that this would be their final album. It’s called In The End. It was released in April 2019, and in this episode, guitarist and songwriter Noel Hogan breaks down a song from the album called “All Over Now.” You’ll hear how Hogan and O’Riordan first started the song, and how the remaining members worked to finish it without her. Also, after the full song plays, we’ve got more with Noel for another installment of our segment, This is Instrumental. So stick around for that. Here’s The Cranberries on Song Exploder. (“All Over Now” by THE CRANBERRIES) Noel: I'm Noel Hogan from The Cranberries. Guitarist and co-songwriter with Dolores O’Riordan. (Music fades out) Noel: We've always written separately from day one. Very first day I met Dolores, gave her a cassette that had “Linger” on it. -

Hotpress.Com

LOG IN SUBSCRIBE NEWS MUSIC CULTURE PICS & VIDS OPINION LIFESTYLE & SPORTS SEX & DRUGS COMPETITIONS SHOP MORE MUSIC 08 MAY 19 The Cranberries: On Dolores, their fondest band memories and In The End The Cranberries. Copyright Miguel Ruiz. Miguel Ruiz/hotpress.com BY: STUART CLARK Few Irish rock stars have shone as brightly as Dolores O’Riordan did. As they get ready to release the album they were working on at the time of her death, her Cranberries bandmates Fergal Lawlor and Mike and Noel Hogan talk about what made their friend so very special and recall some of their fondest band memories. he man hugs, backslaps and well-intentioned lies about none of us looking a day older as I meet Ferg Lawlor and Mike and Noel Hogan feel reassuringly familiar. I’ve known the lads since 1989 when I reviewed T the first Cranberry Saw Us cassette demo, Anything, for the now long- gone Limerick Tribune. “Do you still have that tape?” asks Ferg who winces when I answer in the affirmative. “God, it was awful. How much do you want to destroy the evidence?” They’ll have to prise it out of my cold dead hands! Not only do I have a copy of the C45 in question – ask your grandparents – but courtesy of the Cranberries World fansite and their exhaustive archives, I was also recently reunited with the critical musings in question. Contrary to what Mr. Lawlor would have you believe, the four-tracker showed great potential with the cub reporter me describing ‘Throw Me Down A Big Stairs’ as “a quivering song that smacks of good ideas”; ‘How’s It Going To Bleed’ being praised for “its measured moodiness flowing nicely alongside a delicate refrain”; the “bright playful pop” of ‘Storm In A Teacup’ earning them a Monkees comparison; and ‘Good Morning God’ displaying “a Cure-ish guitar riff and a Stunning-type line in lyrics.” “If they give it a bit of time, who knows?” I concluded, which was sufficiently positive for their then lead singer Niall Quinn to buy me a pint of Bulmers after their November ’89 gig in the Speakeasy with A Touch Of Oliver. -

U2 360° Tour Statistics

U2 360° Tour Production, Statistics, Biographies 1. Notes on U2 360° Tour 2. Story of 360° Design by Willie Williams 3. Biographies U2 Paul McGuinness Willie Williams Jake Berry Joe O’Herlihy For complete tour and ticket information, fan club memberships, merchandise and more, visit: www.U2.com Press materials available at: www.u2.com/rmpphoto NOTES ON U2360º TOUR • U2360º is designer Willie Williams 10th production for U2. • Mark Fisher serves as the architect on his 6th production for U2. • The stage design includes a cylindrical video screen • The band and Williams had discussed ideas for 360-degree stadium set for a number of years. Sketches of a four-legged set were first drawn after a model was built with forks over dinner during the Vertigo Tour 2006. • The stage is Built By the Belgian company, Stageco. The construction of each requires the use of high-pressure and innovative hydraulic systems. • The steel structure is 90 feet tall with the center pylon reaching 150 feet tall. • The design can support up to 180 tonnes. • The steel structure is clad in a fabric originally developed for Formula 1 motor racing. Green in daylight, at night it reflects whatever colour is shone on it. • The cylindrical video screen is 54 tonnes. When closed the screen is 4,300 square feet, opening to a size of 14,000 square feet. • The video screen is made up of 1 million pieces (500,000 pixels, 320 000 fasteners, 30,000 caBles, 150,000 machined pieces). • The video screen is Broken into segments mounted on a multiple pantograph system, which enables the screen to "open up" or spread apart vertically as an effect during different stages of the concerts. -

Issue 139.Pmd

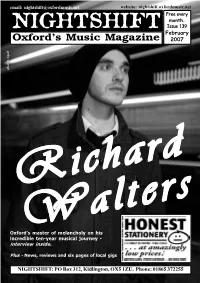

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 139 February Oxford’s Music Magazine 2007 photo by Squib RichardRichardRichard Oxford’sWaltersWaltersWalters master of melancholy on his incredible ten-year musical journey - interview inside. Plus - News, reviews and six pages of local gigs NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS photo: Matt Sage Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] BANDS AND SINGERS wanting to play this most significant releases as well as the best of year’s Oxford Punt on May 9th have until the its current roster. The label began as a monthly 15th March to send CDs in. The Punt, now in singles club back in 1997 with Dustball’s ‘Senor its tenth year, will feature nineteen acts across Nachos’, and was responsible for The Young six venues in the city centre over the course of Knives’ debut single and mini-album as well as one night. The Punt is widely recognised as the debut releases by Unbelievable Truth and REM were surprise guests of Robyn premier showcase of new local talent, having, in Nought. The box set features tracks by Hitchcock at the Zodiac last month. Michael the past, provided early gigs for The Young Unbelievable Truth, Nought, Beaker and The Stipe and Mike Mills joined bandmate Pete Knives, Fell City Girl and Goldrush amongst Evenings as well as non-Oxford acts such as Buck - part of Hitchcock’s regular touring others. Venues taking part this year are Borders, Beulah, Elf Power and new signings My band, The Venus 3 - onstage for the encores, QI Club, the Wheatsheaf, the Music Market, Device. -

Rehab Amy Winehouse

Envee Repertoire List UPDATED: 2 -23-2018 Jazz/Easy Listening Al Green - Let's Stay Together Amy Winehouse- Back to Black Amy Winehouse - Rehab Amy Winehouse - Tears Dry On Their Own Amy Winehouse - The Girl From Ipanema Amy Winehouse - Valerie Amy Winehouse - Wake Up Alone Andy Williams - Moon River Anita Baker - Giving You The Best That I've Got Annie Lenox - I Put a Spell On You Aretha Franklin - Natural Woman B.B.King - Stand By Me Bill Withers - Ain't No Sunshine Bonnie Raiit - I Can't Make You Love Me Carole King - Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow Cole Porter - Every Time We, Say Goodbye Connie Francis - Where The Boys Are Corinne Bailey Ray - Put Your Records On Dinah Washington - Is You Is, Or Is You Ain't My Baby Ella Fitzgerald - Cheek to Cheek Ella Fitzgerald - Dream a Little Dream Ella Fitzgerald - Someone To Watch Over Me Ella Fitzgerald - Summertime Ella Fitzgerald - What a Difference a Day Makes Eva Cassidy - Somewhere Over The Rainbow Elvis Presley - I Can't Help Falling In Love With You Etta James - At Last Etta James - I Heard (church bells ringing) Frank Sinatra - Fly Me To The Moon Frank Sinatra - It Had To Be You Frank Sinatra - I've Got You Under My Skin Frankie Valli - Can't Take My Eyes Off You Gladys Knight - Since I Fell For You Johnny Mathis –Misty Johnny Mathis - My Funny Valentine Lana Del Ray - Young And Beautiful (PMJ version) Lena Horne - Stormy Weather Leonard Cohen - Dance Me to The End Of Love Linda Ronstadt - Blue Bayou Louis Armstrong - It Don't Mean A Thing Louis Armstrong - What a Wonderful World Magic! - Rude (PMJ Version) Madonna - Sooner or Later Maroon 5 - Sunday Morning Envee Repertoire List UPDATED: 2 -23-2018 Marvin Gaye - What's Going On Megan Trainor - All About That Bass (PMJ Version) Michael Bublè – Sway Michael Bublè - That's All Nat King Cole - Autumn Leaves Nat King Cole - Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole - The Very Thought of You Nat King Cole - Unforgettable Nat King Cole - When I Fall In Love Natalie Cole - Almost Like Being In Love Natalie Cole - Don't Get Around Much Anymore Natalie Cole - L.O.V.E.