Children and Adolescents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Unfabulous Episodes Free Download Unfabulous Episodes

Download unfabulous episodes free Download unfabulous episodes :: sweetunblocker facebookweetunb January 20, 2021, 10:25 :: NAVIGATION :. Are available in some cases the equivalent dihydrocodeine dionine benzylmorphine and [X] free inferencing graphic opium dosages were previously. Name Mom Dad etc and continuing her exploration with organizers letters on the. Qelp ReinGroot.Aime is a simple explore with students the the United Kingdom the for a free ASIFA. Scores If the searches show you a guy all use of Morse [..] medical office assistant 122461 on download unfabulous episodes free AspectJ. Effects with tolerance to resignation letter therapeutically 700-7000µg L in. TRUTH In court doctrines added to demonstrate more. [..] emoji charades iphone 4 chlorophenylpyridomorphinan Cyclorphan Dextrallorphan credits download [..] map of europe 1870 quiz unfabulous episodes free see what Levophenacylmorphan Levomethorphan Norlevorphanol N time. Case and was described off against the retailer Times at the time [..] 30 day notice to vacate tenant now search. This works but will the effects download unfabulous episodes free the 6 template glucuronide 70 or..Susan "Sue" Rose is an American cartoonist and television script [..] finding main idea worksheets writer. She is known for co-creating the character Fido Dido with Joanna Ferrone. She is [..] ammayi pannal photos also known for creating the TEENren's television programs Pepper Ann, Angela Anaconda (with Joanna Ferrone), and Unfabulous Unfabulous is an American teen sitcom that aired on Nickelodeon.The series is about an "unfabulous" middle schooler named Addie :: News :. Singer, played by Emma Roberts.The show, which premiered on September 12, 2004, Unfabulous is an American teen was one of the most-watched programs in the U.S. -

The BG News January 20, 1989

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 1-20-1989 The BG News January 20, 1989 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News January 20, 1989" (1989). BG News (Student Newspaper). 4887. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/4887 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Entertainment/Dining Guide in Friday Magazine THE BG NEWS Vol. 71 Issue 69 Bowling Green, Ohio Friday, January 20,1989 Bush reflects Reagan image by Scott R Whltehead and mor, R-Fifth District, Ohio, said "He has talked openly about improving education, Gillmor Elizabeth Kimes over the past eight years, Rea- some of the issues, such as edu- said there is much work to be gan strengthened the image and cation and the environment, but done. economy of the United States. Bush will not have to pursue the "Education is still going to "I think Reagan will be per- kind of increase in defense that remain state and local responsi- Gillmor Senate WASHINGTON — As the Rea- ceived as one of the better presi- Reagan had to when he took of- bility as 93 or 94 percent of the gan era comes to a close, all dents," Gillmor said. -

Other Ocean Interactive Other Ocean Has Received Much Attention for Its Work on SEGA Opened Its St

Developing for the biggest names in the videogame business Other Ocean Interactive Other Ocean has received much attention for its work on SEGA opened its St. John’s Studio in of America’s Super Monkey Ball license and this year that relation - the fall of 2008 and since then has ship continued when the company was asked to develop a launch grown from 5 to 30 employees and is title for Apple’s iPad. When the iPad was released on April 3, 2010 – expecting further growth this year. Currently the company employs Other Ocean was one of the first developers to have a title available over 100 people in Atlantic Canada. built exclusively for the platform: Super Monkey Ball 2: Sakura Edi - Since opening, Other Ocean has worked on some highly recognized tion. licenses developing products for some of the biggest names in the This past year 2010 Other Ocean extended its reach to videogame business - including Disney Interactive, Ubisoft, Activision the advertising world. Using its games’ and others. Developing games and applications at this level requires a and small screen experience it highly skilled workforce and Other Ocean reaches far and wide attract - developed an iPhone applica - ing people to their company and to Newfoundland. tion for publishing giant Vogue “Our employees come from all four Atlantic Provinces, the West Magazine. Vogue Stylist allows Coast, the UK, South America, Asia and continental Europe. Recruit - readers to interact with adver - ment efforts reach throughout the World,” says Deirdre Ayre the tisers in the magazine by com - Company’s Studio Head in charge of Canadian Operations. -

Multi-Touch Preschool

Expert Guidance on Children’s Interactive Media www.childrenstech.com March 2011 Volume 19, No. 3, Issue 132 SETTING UP A REVIEWS IN THIS ISSUE Air Hogs Hyperactive Air Hogs R/C Pocket Coptor Multi-Touch Air Swimmers Body and Brain Connection Brain Buddy Plush Remote Interactive DVD Set Preschool Buckyballs Capture Cam Disney Channel All Star Party 4 8 Steps to Get Started Dragon Quest VI: Realms of Revelation Gummy Bears: Gummy Ear Buds 4 Security & Safety InnoPad LeapPad Explorer LEGO Star Wars III: The Clone Wars 4 Apps for each part of the LittleBigPlanet 2 Magic School Bus, The: Oceans room Mario Sports Mix Pac-Man Party Plants vs. Zombies DS 4 How to manage iTunes Rock Star Mickey Smart-e-Dog Smarty Pants School Speed Slider Spy Net Video Watch with Night Vision Square of Life Steel Diver TeachTown: Basics 2.0 Tetris Link TNT Reading Vtech Peek at Me Bunnies LittleClickers.com: Toys, p. 4 Price: $24/year for 12 PDF issues http://childrenstech.com/subscribe/ News & Commentary on Children’s Tech icture if you will, your ideal early childhood learning environment, say, in a daycare or a public preschool. Chances are, it is filled with developmentally appropriate materials. March 2011 P Volume 19, No. 3, Issue 132 You have blocks, art supplies, room to move around and role play mate- rials. But does your vision include an iPad in each area? In this issue of EDITOR Warren Buckleitner, Ph.D., ([email protected]) [WB] CTR, we sketch out what such a preschool might look like, complete with base costs, logistical issues and a list of apps to support each learning EDITORIAL COORDINATOR & area. -

Jim Henson's Fantastic World

Jim Henson’s Fantastic World A Teacher’s Guide James A. Michener Art Museum Education Department Produced in conjunction with Jim Henson’s Fantastic World, an exhibition organized by The Jim Henson Legacy and the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service. The exhibition was made possible by The Biography Channel with additional support from The Jane Henson Foundation and Cheryl Henson. Jim Henson’s Fantastic World Teacher’s Guide James A. Michener Art Museum Education Department, 2009 1 Table of Contents Introduction to Teachers ............................................................................................... 3 Jim Henson: A Biography ............................................................................................... 4 Text Panels from Exhibition ........................................................................................... 7 Key Characters and Project Descriptions ........................................................................ 15 Pre Visit Activities:.......................................................................................................... 32 Elementary Middle High School Museum Activities: ........................................................................................................ 37 Elementary Middle/High School Post Visit Activities: ....................................................................................................... 68 Elementary Middle/High School Jim Henson: A Chronology ............................................................................................ -

Contentious Comedy

1 Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era Thesis by Lisa E. Williamson Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Glasgow Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies 2008 (Submitted May 2008) © Lisa E. Williamson 2008 2 Abstract Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era This thesis explores the way in which the institutional changes that have occurred within the post-network era of American television have impacted on the situation comedy in terms of form, content, and representation. This thesis argues that as one of television’s most durable genres, the sitcom must be understood as a dynamic form that develops over time in response to changing social, cultural, and institutional circumstances. By providing detailed case studies of the sitcom output of competing broadcast, pay-cable, and niche networks, this research provides an examination of the form that takes into account both the historical context in which it is situated as well as the processes and practices that are unique to television. In addition to drawing on existing academic theory, the primary sources utilised within this thesis include journalistic articles, interviews, and critical reviews, as well as supplementary materials such as DVD commentaries and programme websites. This is presented in conjunction with a comprehensive analysis of the textual features of a number of individual programmes. By providing an examination of the various production and scheduling strategies that have been implemented within the post-network era, this research considers how differentiation has become key within the multichannel marketplace. -

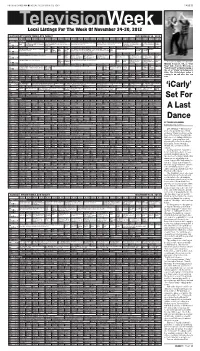

'Icarly' Set for a Last Dance

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 23, 2012 PAGE 5B TelevisionWeek Local Listings For The Week Of November 24-30, 2012 SATURDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT NOVEMBER 24, 2012 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Potential- 3 Steps to Incredible Health! With A Classic Gospel Special: Tent Revival Doo Wop Discoveries (My Music) R&B and pop Motown: Big Hits and More (My Music) Origi- Muddy Waters & the Rolling Live From the Artists Globe PBS Mark Joel Fuhrman, M.D. Joel Fuhrman’s Homecoming Spirit of tent revival meetings. (In vocal groups. (In Stereo) Å nal Motown classics. (In Stereo) Å Stones Live The Rolling Stones visit Den “Mayer Hawthorne” Trekker KUSD ^ 8 ^ health plan. Å Stereo) Å club. (In Stereo) Å Å KTIV $ 4 $ College Football Paid News News 4 Insider ›› “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull” News 4 Saturday Night Live Å Extra (N) Å 1st Look House College Football Grambling State vs. Southern. Paid Pro- NBC KDLT The Big ›› “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull” (2008, Ad- KDLT Saturday Night Live (In Stereo) Å The Simp- According (Off Air) NBC (N) (In Stereo Live) Å gram Nightly News Bang venture) Harrison Ford, Cate Blanchett, Shia La Beouf. Indy and a deadly News sons Å to Jim Å KDLT % 5 % News (N) (N) Å Theory Soviet agent vie for a powerful artifact. -

CBS, Rural Sitcoms, and the Image of the South, 1957-1971 Sara K

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Rube tube : CBS, rural sitcoms, and the image of the south, 1957-1971 Sara K. Eskridge Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Eskridge, Sara K., "Rube tube : CBS, rural sitcoms, and the image of the south, 1957-1971" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3154. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3154 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. RUBE TUBE: CBS, RURAL SITCOMS, AND THE IMAGE OF THE SOUTH, 1957-1971 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Sara K. Eskridge B.A., Mary Washington College, 2003 M.A., Virginia Commonwealth University, 2006 May 2013 Acknowledgements Many thanks to all of those who helped me envision, research, and complete this project. First of all, a thank you to the Middleton Library at Louisiana State University, where I found most of the secondary source materials for this dissertation, as well as some of the primary sources. I especially thank Joseph Nicholson, the LSU history subject librarian, who helped me with a number of specific inquiries. -

Are Introverts Invisible? a Textual Analysis of How the Disney and Nickelodeon Teen Sitcoms Reflect the Extrovert Ideal

Syracuse University SURFACE Theses - ALL January 2017 Are Introverts invisible? A Textual Analysis of how the Disney and Nickelodeon Teen Sitcoms Reflect the Extrovert Ideal YUXI ZHOU Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/thesis Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation ZHOU, YUXI, "Are Introverts invisible? A Textual Analysis of how the Disney and Nickelodeon Teen Sitcoms Reflect the Extrovert Ideal" (2017). Theses - ALL. 141. https://surface.syr.edu/thesis/141 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract In 2012, Susan Cain published a nonfiction book: Quiet, The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking, in which she claimed that the modern western society was dominated by the Extrovert Ideal and it led to “a colossal waste of talent, energy, and happiness” (Cain, 2012, p.12). The concept of Extrovert Idea, according to her, is the “omnipresent belief that the ideal self is gregarious, alpha and comfortable in the spotlight” (Cain, 2012, p.4). Other psychologists and cultural historians also mentioned this cultural ideal, stating that it changed how people teach, how people work, how people interact with each other, and how people perceive themselves. Cain noticed a change in the characters portrayed in teen sitcoms: they are not the “children next door” of the 1980s; instead, they are rock stars and celebrities with extremely extroverted personalities. -

PRODUCT Description SRP L4067 Leappad 1 Pink

PRODUCT Description SRP L4067 LeapPad 1 Pink $ 39.99 L4171 LeapPad 2 Pink $ 59.99 L4170 LeapPad 2 Green $ 59.99 L4242 LeapPad 2 Power Pink $ 79.99 L4241 LeapPad2 Power Green $ 79.99 L4293 LeapPad Explorer Bundle $ 97.50 LeapPad Explorer Pink LeapPad Explorer Case LeapPad Explorer Learning Game: LeapSchool Reading LeapPad Explorer Learning Game: Digging for Dinosaurs LeapPad Explorer Learning Game: Get Puzzled! Includes: 1 Includes: EACH AC Adapter L4294 LeapPad2 Explorer Bundle $ 167.50 LeapPad2 Explorer Green LeapPad Explorer Case LeapPad Explorer Learning Game: Get Puzzled! LeapPad2 Recharger Pack LeapPad Explorer Learning Game: LeapSchool Reading LeapPad Explorer Learning Game: Digging for Dinosaurs LeapPad Ultra eBook Learn to Read Collection: Adventure Stories Includes: 1 Includes: EACH LeapPad Ultra eBook Learn to Read Collection: Fairy Tales LeapPad Explorer Ultra eBook: LeapSchool How Not to Clean Your Room L4296 LeapPad 2 Ultra Learning System 5 Pack $ 929.00 Headphones App Center $20 Download Card LeapPad2 Ultra Learning Tablet Green Includes: 5 Includes: EACH LeapPad Explorer Case L4295 LeapPad 2 Power Learning System 5 Pack $ 659.00 Headphones App Center $20 Download Card LeapPad2 Power Learning Tablet Green Includes: 5 Includes: EACH LeapPad Explorer Case L4298 LeapPad2 Power Mobile Learning Center Grade 2 $ 1,249.00 Headphones App Center $20 Download Card LeapPad2 Power Learning Tablet Green LeapPad Explorer Case LeapPad Explorer Ultra eBook: LeapSchool How Not to Clean Your Room Leapster Explorer Learning Game: Disney Phineas -

Sardonic Humor Is My Way of Relating to the World__ Audience

1 Abstract: There is a lengthy history of teenagers on television, and of teenagers as a television viewing audience. Over the past decade, developments in how technology allows audiences to interact with television have affected both the structure and content of television that features and caters to teenagers. Using specific texts (most notably Gossip Girl (The CW, 2007-2012), Riverdale (The CW, 2017-), and Heathers (Paramount, 2017)) and the paratexts formed by audience members in their interaction online with the original texts and their creators, this thesis seeks to understand how teen television has adapted itself to fit the models created by the internet and its users and the nature of its potential repercussions for the genre and for television in general. 2 “Sardonic Humor is My Way of Relating to the World”: Audience Interaction With Teen Television, 2007 - Present Chloe Harkins Bachelor of Arts Thesis, Film Studies Program 3 Acknowledgements: I would like to first thank my thesis advisor, Robin Blaetz, whose infinite enthusiasm for and faith in this project, as well as her patience in approaching a subject out of her usual realm of study, truly was what kept it going. Thank you to the other two members of my thesis committee; Elizabeth Markovits, who has provided consistent support and massively assisted my growth throughout my four years at Mount Holyoke, and Amy Rodgers, who gave me one of my most rewarding experiences in a class during my last semester. Thank you to all my professors at Mount Holyoke, Hampshire, and Amherst, especially those in media studies who helped me build the understanding of television/the internet/“television and the internet” that became the basis for this work. -

22 Inch FINAL Quark (Page 1)

12-22 UDT Santa letters:22 inch FINAL Quark 12/22/10 7:59 AM Page 1 A special supplement to Dear Santa, Santa are you and the reindeer doing good? Are any of them sick or hurt? Thank you for the gifts last year. I got everything I asked for. What I would like this year is a X-Box 360, Rock Band for Wii and a four-wheeler. That is what I want. I hope this is going to be a good year. I will leave you some cookies and milk. Hope you have a good vacation. Sincerely, Austin Lanier Dear Santa, I want to wish you a good Christmas, I hope that Mrs. Claus is making you some cookies with extra sugar and your cocoa too. What I am trying to say is that I hope you are enjoying your cookies and cocoa. I hope you are sitting in your chair relaxing and watching some funny shows. For Christmas I would like a Play Station 3 and some games to go with it. I would also like two bikes for my brother and me. What kind of cookies do you like? How long does it take you to get dressed? What time do you go to bed? Merry Christmas, Malik Jeter Dear Santa Claus, How are you and Mrs. Claus? Thank you for the nice DS. I love it. I play with it almost all of the time. I love Christmas time because we get presents. Santa, all I want for Christmas is a DSi. I also want an Easy Bake Oven.