Indigenous Pop: Native American Music from Jazz to Hip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking Intellectual Property Into Their Own Hands

Taking Intellectual Property into Their Own Hands Amy Adler* & Jeanne C. Fromer** When we think about people seeking relief for infringement of their intellectual property rights under copyright and trademark laws, we typically assume they will operate within an overtly legal scheme. By contrast, creators of works that lie outside the subject matter, or at least outside the heartland, of intellectual property law often remedy copying of their works by asserting extralegal norms within their own tight-knit communities. In recent years, however, there has been a growing third category of relief-seekers: those taking intellectual property into their own hands, seeking relief outside the legal system for copying of works that fall well within the heartland of copyright or trademark laws, such as visual art, music, and fashion. They exercise intellectual property self-help in a constellation of ways. Most frequently, they use shaming, principally through social media or a similar platform, to call out perceived misappropriations. Other times, they reappropriate perceived misappropriations, therein generating new creative works. This Article identifies, illustrates, and analyzes this phenomenon using a diverse array of recent examples. Aggrieved creators can use self-help of the sorts we describe to accomplish much of what they hope to derive from successful infringement litigation: collect monetary damages, stop the appropriation, insist on attribution of their work, and correct potential misattributions of a misappropriation. We evaluate the benefits and demerits of intellectual property self-help as compared with more traditional intellectual property enforcement. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38KP7TR8W Copyright © 2019 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Inc. -

Diana Davies Photograph Collection Finding Aid

Diana Davies Photograph Collection Finding Aid Collection summary Prepared by Stephanie Smith, Joyce Capper, Jillian Foley, and Meaghan McCarthy 2004-2005. Creator: Diana Davies Title: The Diana Davies Photograph Collection Extent: 8 binders containing contact sheets, slides, and prints; 7 boxes (8.5”x10.75”x2.5”) of 35 mm negatives; 2 binders of 35 mm and 120 format negatives; and 1 box of 11 oversize prints. Abstract: Original photographs, negatives, and color slides taken by Diana Davies. Date span: 1963-present. Bulk dates: Newport Folk Festival, 1963-1969, 1987, 1992; Philadelphia Folk Festival, 1967-1968, 1987. Provenance The Smithsonian Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections acquired portions of the Diana Davies Photograph Collection in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when Ms. Davies photographed for the Festival of American Folklife. More materials came to the Archives circa 1989 or 1990. Archivist Stephanie Smith visited her in 1998 and 2004, and brought back additional materials which Ms. Davies wanted to donate to the Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives. In a letter dated 12 March 2002, Ms. Davies gave full discretion to the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage to grant permission for both internal and external use of her photographs, with the proviso that her work be credited “photo by Diana Davies.” Restrictions Permission for the duplication or publication of items in the Diana Davies Photograph Collection must be obtained from the Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections. Consult the archivists for further information. Scope and Content Note The Davies photographs already held by the Rinzler Archives have been supplemented by two more recent donations (1998 and 2004) of additional photographs (contact sheets, prints, and slides) of the Newport Folk Festival, the Philadelphia Folk Festival, the Poor People's March on Washington, the Civil Rights Movement, the Georgia Sea Islands, and miscellaneous personalities of the American folk revival. -

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

JUKEBOX JAZZ by Ian Muldoon* ______

JUKEBOX JAZZ by Ian Muldoon* ____________________________________________________ n 1955 Bill Haley’s Rock Around the Clock was the first rock and roll record to become number one on the hit parade. It had made a stunning introduction in I the opening moments to a film called Blackboard Jungle. But at that time my favourite record was one by Lionel Hampton. I was not alone. Me and my three jazz loving friends couldn’t be bothered spending hard-earned cash on rock and roll records. Our quartet consisted of clarinet, drums, bass and vocal. Robert (nickname Orgy) was learning clarinet; Malcolm (Slim) was going to learn drums (which in due course he did under the guidance of Gordon LeCornu, a percussionist and drummer in the days when Sydney still had a thriving show scene); Dave (Bebop) loved the bass; and I was the vocalist a la Joe (Bebop) Lane. We were four of 120 RAAF apprentices undergoing three years boarding school training at Wagga Wagga RAAF Base from 1955-1957. Of course, we never performed together but we dreamt of doing so and luckily, dreaming was not contrary to RAAF regulations. Wearing an official RAAF beret in the style of Thelonious Monk or Dizzy Gillespie, however, was. Thelonious Monk wearing his beret the way Dave (Bebop) wore his… PHOTO CREDIT WILLIAM P GOTTLIEB _________________________________________________________ *Ian Muldoon has been a jazz enthusiast since, as a child, he heard his aunt play Fats Waller and Duke Ellington on the household piano. At around ten years of age he was given a windup record player and a modest supply of steel needles, on which he played his record collection, consisting of two 78s, one featuring Dizzy Gillespie and the other Fats Waller. -

The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBoRAh F. RUTTER, President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 16, 2018, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters TODD BARKAN JOANNE BRACKEEN PAT METHENY DIANNE REEVES Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz. This performance will be livestreamed online, and will be broadcast on Sirius XM Satellite Radio and WPFW 89.3 FM. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 2 THE 2018 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts DEBORAH F. RUTTER, President of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts The 2018 NEA JAzz MASTERS Performances by NEA Jazz Master Eddie Palmieri and the Eddie Palmieri Sextet John Benitez Camilo Molina-Gaetán Jonathan Powell Ivan Renta Vicente “Little Johnny” Rivero Terri Lyne Carrington Nir Felder Sullivan Fortner James Francies Pasquale Grasso Gilad Hekselman Angélique Kidjo Christian McBride Camila Meza Cécile McLorin Salvant Antonio Sanchez Helen Sung Dan Wilson 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 -

The History and Development of Jazz Piano : a New Perspective for Educators

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1975 The history and development of jazz piano : a new perspective for educators. Billy Taylor University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Taylor, Billy, "The history and development of jazz piano : a new perspective for educators." (1975). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 3017. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/3017 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. / DATE DUE .1111 i UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS LIBRARY LD 3234 ^/'267 1975 T247 THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS A Dissertation Presented By William E. Taylor Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfil Iment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF EDUCATION August 1975 Education in the Arts and Humanities (c) wnii aJ' THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO: A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS A Dissertation By William E. Taylor Approved as to style and content by: Dr. Mary H. Beaven, Chairperson of Committee Dr, Frederick Till is. Member Dr. Roland Wiggins, Member Dr. Louis Fischer, Acting Dean School of Education August 1975 . ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO; A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS (AUGUST 1975) William E. Taylor, B.S. Virginia State College Directed by: Dr. -

88-Page Mega Version 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010

The Gift Guide YEAR-LONG, ALL OCCCASION GIFT IDEAS! 88-PAGE MEGA VERSION 2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010 COMBINED jazz & blues report jazz-blues.com The Gift Guide YEAR-LONG, ALL OCCCASION GIFT IDEAS! INDEX 2017 Gift Guide •••••• 3 2016 Gift Guide •••••• 9 2015 Gift Guide •••••• 25 2014 Gift Guide •••••• 44 2013 Gift Guide •••••• 54 2012 Gift Guide •••••• 60 2011 Gift Guide •••••• 68 2010 Gift Guide •••••• 83 jazz &blues report jazz & blues report jazz-blues.com 2017 Gift Guide While our annual Gift Guide appears every year at this time, the gift ideas covered are in no way just to be thought of as holiday gifts only. Obviously, these items would be a good gift idea for any occasion year-round, as well as a gift for yourself! We do not include many, if any at all, single CDs in the guide. Most everything contained will be multiple CD sets, DVDs, CD/DVD sets, books and the like. Of course, you can always look though our back issues to see what came out in 2017 (and prior years), but none of us would want to attempt to decide which CDs would be a fitting ad- dition to this guide. As with 2016, the year 2017 was a bit on the lean side as far as reviews go of box sets, books and DVDs - it appears tht the days of mass quantities of boxed sets are over - but we do have some to check out. These are in no particular order in terms of importance or release dates. -

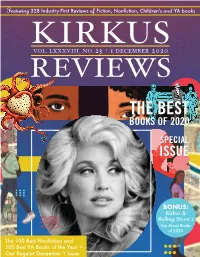

Kirkus Best Books of 2020

Featuring 328 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 23 | 1 DECEMBER 2020 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE BONUS: Kirkus & Rolling Stone’s Top Music Books of 2020 The 100 Best Nonfiction and 100 Best YA Books of the Year + Our Regular December 1 Issue from the editor’s desk: Books That Deserved More Buzz Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Editor-in-Chief Every December, I look back on the year past and give a shoutout to those TOM BEER books that deserved more buzz—more reviews, more word-of-mouth [email protected] Vice President of Marketing promotion, more book-club love, more Twitter excitement. It’s a subjec- SARAH KALINA tive assessment—how exactly do you measure buzz? And how much is not [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor enough?—but I relish the exercise because it lets me revisit some titles ERIC LIEBETRAU that merit a second look. [email protected] Fiction Editor Of course, in 2020 every book deserved more buzz. Between the pan- LAURIE MUCHNICK demic and the presidential election, it was hard for many titles, deprived [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor of their traditional publicity campaigns, to get the attention they needed. VICKY SMITH A few lucky titles came out early in the year, disappeared when coronavi- [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor rus turned our world upside down, and then managed to rebound; Douglas LAURA SIMEON [email protected] Stuart’s Shuggie Bain (Grove, Feb. -

Compositions-By-Frank-Zappa.Pdf

Compositions by Frank Zappa Heikki Poroila Honkakirja 2017 Publisher Honkakirja, Helsinki 2017 Layout Heikki Poroila Front cover painting © Eevariitta Poroila 2017 Other original drawings © Marko Nakari 2017 Text © Heikki Poroila 2017 Version number 1.0 (October 28, 2017) Non-commercial use, copying and linking of this publication for free is fine, if the author and source are mentioned. I do not own the facts, I just made the studying and organizing. Thanks to all the other Zappa enthusiasts around the globe, especially ROMÁN GARCÍA ALBERTOS and his Information Is Not Knowledge at globalia.net/donlope/fz Corrections are warmly welcomed ([email protected]). The Finnish Library Foundation has kindly supported economically the compiling of this free version. 01.4 Poroila, Heikki Compositions by Frank Zappa / Heikki Poroila ; Front cover painting Eevariitta Poroila ; Other original drawings Marko Nakari. – Helsinki : Honkakirja, 2017. – 315 p. : ill. – ISBN 978-952-68711-2-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-68711-2-7 Compositions by Frank Zappa 2 To Olli Virtaperko the best living interpreter of Frank Zappa’s music Compositions by Frank Zappa 3 contents Arf! Arf! Arf! 5 Frank Zappa and a composer’s work catalog 7 Instructions 13 Printed sources 14 Used audiovisual publications 17 Zappa’s manuscripts and music publishing companies 21 Fonts 23 Dates and places 23 Compositions by Frank Zappa A 25 B 37 C 54 D 68 E 83 F 89 G 100 H 107 I 116 J 129 K 134 L 137 M 151 N 167 O 174 P 182 Q 196 R 197 S 207 T 229 U 246 V 250 W 254 X 270 Y 270 Z 275 1-600 278 Covers & other involvements 282 No index! 313 One night at Alte Oper 314 Compositions by Frank Zappa 4 Arf! Arf! Arf! You are reading an enhanced (corrected, enlarged and more detailed) PDF edition in English of my printed book Frank Zappan sävellykset (Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys 2015, in Finnish). -

Music in the Digital Age: Musicians and Fans Around the World “Come Together” on the Net

Music in the Digital Age: Musicians and Fans Around the World “Come Together” on the Net Abhijit Sen Ph.D Associate Professor Department of Mass Communications Winston-Salem State University Winston-Salem, North Carolina U.S.A. Phone: (336) 750-2434 (o) (336) 722-5320 (h) e-mail: [email protected] Address: 3841, Tangle Lane Winston-Salem, NC. 27106 U.S.A. Bio: Currently an Associate Professor in the Department of Mass Communications, Winston-Salem State University. Research on international communications and semiotics have been published in Media Asia, Journal of Development Communication, Parabaas, Proteus and Acta Semiotica Fennica. Teach courses in international communications and media analysis. Keywords: music/ digital technology/ digital music production/music downloading/ musicians on the Internet/ music fans/ music software Abstract The convergence of music production, creation, distribution, exhibition and presentation enabled by the digital communications technology has swept through and shaken the music industry as never before. With a huge push from the digital technology, music is zipping around the world at the speed of light bringing musicians, fans and cultures together. Digital technology has played a major role in making different types of music accessible to fans, listeners, music lovers and downloaders all over the world. The world of music production, consumption and distribution has changed, and the shift is placing the power back into the hands of the artists and fans. There are now solutions available for artists to distribute their music directly to the public while staying in total control of all the ownership, rights, creative process, pricing, release dates and more. -

Open Steinle Cory Kanyecriticism.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION ARTS & SCIENCES “I THOUGHT ABOUT KILLING YOU”: CONSIDERING THE UTILITY OF RHETORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL CRITICAL APPROACHES TO KANYE WEST’S YE CORY N. STEINLE SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Communication Arts and Sciences and Labor and Employment Relations with honors in Communication Arts and Sciences Reviewed and approved* by the following: Bradford Vivian Professor of Communication Arts & Sciences Thesis Supervisor Lori Bedell Associate Teaching Professor in Communication Arts & Sciences Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT This paper examines the merits of intrinsic and extrinsic critical approaches to hip-hop artifacts. To do so, I provide both a neo-Aristotelian and biographical criticism of three songs from ye (2018) by Kanye West. Chapters 1 & 2 consider Roland Barthes’ The Death of the Author and other landmark papers in rhetorical and literary theory to develop an intrinsic and extrinsic approach to criticizing ye (2018), evident in Tables 1 & 2. Chapter 3 provides the biographical antecedents of West’s life prior to the release of ye (2018). Chapters 4, 5, & 6 supply intrinsic (neo-Aristotelian) and extrinsic (biographical) critiques of the selected artifacts. Each of these chapters aims to address the concerns of one of three guiding questions: which critical approaches prove most useful to the hip-hop consumer listening to this song? How can and should the listener construct meaning? Are there any improper ways to critique and interpret this song? Chapter 7 discusses the variance in each mode of critical analysis from Chapters 4, 5, & 6. -

I Giovani Americani Contro Le Armi

30 mar/5 apr 2018n. 1249 • anno 25 internazionale.it 4,00 € Ogni settimana Oceania Etiopia Inchiesta il meglio dei giornali Le isole La fabbrica dei vestiti Il nemico numero uno di tutto il mondo fragili a basso costo di Facebook La rivolta I giovani americani P T C A IN CH T E • • AU D • PED • CHF S contro le armi I, P NT DCB VR • CO F CH E T • • PT AR • HF TIMANALE C SET BE UK DL 30 marzo/5 aprile 2018 • Numero 1249 • Anno 25 “Le domande cominciano a sofocarmi” Sommario AHLAM BSHARAT A PAGINA 100 3 0 m a r / 5 a p r 2 0 1 8n. 1 2 4 9 • a n n o 25 internazionale. i t 4,0 0 € O g n i set t i m a n a O c e a n i a E t i o p ia I n c h i e sta i l m e g l i o d e i gi o r n a l i Le i s o l e L a fa b b r i c a de i v e s t i t i I l n e m i c o nu m e r o u n o IN COPERTINA La settimana d i t u t t o i l mondo f r a g i l i a b a s s o co s t o d i F a c e book Giovani ribelli americani L a r i v o l t a I g i o v ani americani c o n t r o l e a r m i Gli studenti sopravvissuti alla strage di Parkland, in Florida, hanno Approfondire dato vita a un movimento contro le armi che sta ottenendo risultati sorprendenti.