Football Fandom, Mobilization and Herbert Blumer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Etoth Dissertation Corrected.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School The College of Arts and Architecture FROM ACTIVISM TO KIETISM: MODERIST SPACES I HUGARIA ART, 1918-1930 BUDAPEST – VIEA – BERLI A Dissertation in Art History by Edit Tóth © 2010 Edit Tóth Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 The dissertation of Edit Tóth was reviewed and approved* by the following: Nancy Locke Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Head of the Department of Art History Michael Bernhard Associate Professor of Political Science *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT From Activism to Kinetism: Modernist Spaces in Hungarian Art, 1918-1930. Budapest – Vienna – Berlin investigates modernist art created in Central Europe of that period, as it responded to the shock effects of modernity. In this endeavor it takes artists directly or indirectly associated with the MA (“Today,” 1916-1925) Hungarian artistic and literary circle and periodical as paradigmatic of this response. From the loose association of artists and literary men, connected more by their ideas than by a distinct style, I single out works by Lajos Kassák – writer, poet, artist, editor, and the main mover and guiding star of MA , – the painter Sándor Bortnyik, the polymath László Moholy- Nagy, and the designer Marcel Breuer. This exclusive selection is based on a particular agenda. First, it considers how the failure of a revolutionary reorganization of society during the Hungarian Soviet Republic (April 23 – August 1, 1919) at the end of World War I prompted the Hungarian Activists to reassess their lofty political ideals in exile and make compromises if they wanted to remain in the vanguard of modernity. -

Class of 1959 55 Th Reunion Yearbook

Class of 1959 th 55 Reunion BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY 55th Reunion Special Thanks On behalf of the Offi ce of Development and Alumni Relations, we would like to thank the members of the Class of 1959 Reunion Committee Michael Fisher, Co-chair Amy Medine Stein, Co-chair Rosalind Fuchsberg Kaufman, Yearbook Coordinator I. Bruce Gordon, Yearbook Coordinator Michael I. Rosen, Class Gathering Coordinator Marilyn Goretsky Becker Joan Roistacher Blitman Judith Yohay Glaser Sally Marshall Glickman Arlene Levine Goldsmith Judith Bograd Gordon Susan Dundy Kossowsky Fern Gelford Lowenfels Barbara Esner Roos Class of 1959 Timeline World News Pop Culture Winter Olympics are held in Academy Award, Best Picture: Marty Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy Elvis Presley enters the US music charts for fi rst Summer Olympics are held in time with “Heartbreak Hotel” Melbourne, Australia Black-and-white portable TV sets hit the market Suez Crisis caused by the My Fair Lady opens on Broadway Egyptian Nationalization of the Suez Canal Th e Wizard of Oz has its fi rst airing on TV Prince Ranier of Monaco Videocassette recorder is invented marries Grace Kelly Books John Barth - Th e Floating Opera US News Kay Th ompson - Eloise Alabama bus segregation laws declared illegal by US Supreme Court James Baldwin - Giovanni’s Room Autherine Lucy, the fi rst black student Allen Ginsburg - Howl at the University of Alabama, is suspended after riots Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 signed into law for the construction of 41,000 miles of interstate highways over a 20-year period Movies Guys and Dolls Th e King and I Around the World in Eighty Days Economy Gallon of gas: 22 cents Average cost of a new car: $2,050 Ground coff ee (per lb.): 85 cents First-class stamp: 3 cents Died this Year Connie Mack Tommy Dorsey 1956 Jackson Pollock World News Pop Culture Soviet Union launches the fi rst Academy Award, Best Picture: Around the World space satellite Sputnik 1 in 80 Days Soviet Union launches Sputnik Leonard Bernstein’s West Side Story debuts on 2. -

1 FC UNITED LIMITED Trading As FC United of Manchester NOTICE of An

FC UNITED LIMITED Trading as FC United of Manchester NOTICE of an extraordinary General Meeting NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that an extraordinary General Meeting of FC United Limited will take place on Saturday 25th June 2016, at Longfield Suite, 3 Longfield Centre, Prestwich M25 1AY. The meeting will commence at noon. Registration opens at 11.00am. The meeting will consider the following business: 1. Chair’s Welcome and Election of Scrutineers 2. Questions for candidates Re-Open Nominations Members who feel that some or all candidates are unsuitable may indicate this by voting to re-open nominations. Lawrence Gill This nomination is supported by Blaine Emmett, Nick Duckett, Alex Jones, Peter Wharton, Robin Squelch. I’m Lawrence Gill, co-owner, founder member and season ticket holder since 2005. Prior to that I was a season ticket holder and shareholder at OT. As FC we have achieved so much in a short space of time. However, that progress has not been without its difficulties and the last twelve months have been difficult. I think it’s inevitable that, given our roots as a bunch of ‘arsey’, opinionated Mancunians, we have differing opinions on how we see progress to date and what should happen next. Consensus isn’t always achievable. But we are a democratic organisation and that brings a responsibility on all of us to listen to the opinions of others in a respectful way and decide as a majority on the way forward. I think we have scored a few own goals over the past few months. As members, we rely on communication from the club. -

In Search of the Truefan: from Antiquity to the End Of

IN SEARCH OF THE TRUEFAN: POPULISM, FOOTBALL AND FANDOM IN ENGLAND FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE END OF THE TWENTlETH CENTURY Aleksendr Lim B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1997 THESIS SUBMITTED iN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History O Aleksendr Lim 2000 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY January 2000 Al1 rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. National Library Biblioth&que nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie Weilington Ottawa ON KlAON4 WwaON K1A ON4 Canada CaMda Yaurhh Vam &lima Our W Wro&lk.nc. The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive Licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in rnicrofom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic fonnats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT The average soccer enthusiast has a lot to feel good about with regard to the sbte of the English game as it enters the twenty-first century. -

The Greatest History by «Manchester United»

УДК 796.332(410.176.11):811.111 Kostykevich P., Mileiko A. The greatest history by «Manchester United» Belarusian National Technical University Minsk, Belarus Manchester United are an English club in name and a У global club in nature. They were the first English side to playТ in the European Cup and the first side to win it, and they are the only English side to have become world club champions.Н In addition, the Munich Air Disaster of 1958, which wiped out one of football's great young sides, changed the clubБ indelibly. The club was founded in 1878 as Newton Heath LYR Football Club by workers at the Lancashire and Yorkshire 1 й Railway Depot . They played in the Football League for the first time in 1892, but were relegated иtwo years later. The club became Manchester United in 1902,р when a group of local businessmen took over. It was then that they adopted the red shirt for which United would оbecome known. The new club won theirт first league championships under Ernest Mangnall in 1908 and 1911, adding their first FA Cup in 1909. Mangnall left toи join Manchester City in 1911, however, and there would зbe no more major honours until after the Second World War. In that timeо United had three different spells in Division Two, beforeп promotion in 1938 led to an extended spell in the top flight. The key to that was the appointment of the visionary Matt еBusby in 1945. Busby reshaped the club, placing Рcomplete faith in a youth policy that would prove astonishingly successful. -

Der FC United of Manchester

BACHELORARBEIT Herr Sebastian Kristen Die Entwicklung des engli- schen Fußballs – Vom Peo- ple´s Game zum Rich Man´s Game? – aufgezeigt am Bei- spiel von Manchester United FC 2014 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Die Entwicklung des engli- schen Fußballs – Vom Peo- ple´s Game zum Rich Man´s Game? – aufgezeigt am Bei- spiel von Manchester United FC Autor: Herr Sebastian Kristen Studiengang: Angewandte Medienwirtschaft Seminargruppe: AM09wS1-B Erstprüfer: Prof. Dr. phil. Otto Altendorfer Zweitprüferin: Frau Barbara Suhr Einreichung: Ort, Datum Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS The development of the Eng- lish Football – From a Peo- ple´s Game to a Rich Man´s Game? – shown by the ex- ample of Manchester United FC author: Mr. Sebastian Kristen course of studies: Angewandte Medienwirtschaft seminar group: AM09wS1-B first examiner: Prof. Dr. phil. Otto Altendorfer second examiner: Ms. Barbara Suhr submission: Eckernförde, Datum Bibliografische Angaben Nachname, Vorname: Kristen, Sebastian Thema der Bachelorarbeit: Die Entwicklung des englischen Fußballs – Vom People´s Game zum Rich Man´s Game? – aufgezeigt am Beispiel von Manchester United FC Topic of thesis: The development of the English football – From a People´s Game to a Rich Man´s Game? – shown by the example of Manchester United FC 59 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2014 Inhaltsverzeichnis V Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis.........................................................................................................V -

Rights Guide • Non-Fiction

rights guide • non-fiction 1 | P a g e Index Most Acclaimed Stories Page 3 Autobiography and Memoir Page 6 True Stories of Resilience Page 6 Protagonists of Our Times Page 8 Witnesses To History Page 11 Against All Odds Page 15 Cultural Diversity Page 16 Witty, Light-hearted and Uplifting Stories Page 19 Inspirational Stories Page 23 Mental, Dysfanctional, Abuse Page 27 Biography Page 31 True Crime Page 36 Doctor’s Stories Page 38 A Little British Collection Page 44 History Page 48 2 | P a g e Most Acclaimed The Crate Escape Brian Robson The Crate Escape is the true story of a teen, who in 1962, emigrated from his hometown, Cardiff, to Australia. His return, some eleven months later, caused a worldwide stir as he airmailed himself home and become the first and only person ever to fly the Pacific Ocean in a crate. His story is currently being made into a feature film and is the subject of a BBC Television documentary. In 1962, when air-travel was in its infancy, a nineteen-year-old boy who felt trapped in Melbourne, Australia, made up his mind that he was going to return to his homeland in the United Kingdom. He was prevented from doing so by both lack of documentation and the funds required. Putting an idea to work without the thought of losing his life, he became the first person in history to fly for nearly five days in a crate across the Pacific Ocean. The Author Brian Robson was born in the United Kingdom in June 1945 and has spent most of his adult life travelling and living in various countries throughout Europe and South East Asia. -

The Commemorative Activity at The

The Commemorative Activity at the Grave of Munich Air Disaster Victim, Duncan Edwards: A Social and Cultural Analysis of the Commemorative Networks of a Local Sporting Hero by Gayle Rogers A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire July 2017 ABSTRACT The Commemorative Activity at the Grave of Munich Air Disaster Victim, Duncan Edwards: A Social and Cultural Analysis of the Commemorative Networks of a Local Sporting Hero The Munich Air Disaster claimed the lives of 23 people in a plane crash in Munich in 1958. It is a significant event within modern England’s cultural history as a number of Manchester United footballers, known as the Busby Babes were amongst the dead. The players who died have continued to be extensively commemorated, especially Duncan Edwards. This research considers the commemorative activity associated with Edwards since his death and was initiated when the researcher pondered the extensive commemorative activity by strangers that she encountered at the family grave of her cousin Edwards. The commemoration of the Disaster and of Edwards has been persistent and various with new acts of commemoration continuing conspicuously even after fifty years since the event. Such unique activity particularly demonstrated at Edwards’ grave was considered worthy of further investigation to ascertain why such activity was occurring at such a volume. Although general historical and biographical accounts of the Disaster and Edwards are apparent, specific research concerning the commemoration of the event was not evident. The researcher set out to identify who the commemorators were, why they were undertaking dedicatory acts and what those acts manifest as. -

Manchester United - Ramblings of a Nostalgic Old Red

A compilation of 43 articles written on the subject of soccer. Manchester United - Ramblings of a Nostalgic Old Red by Thomas Clare Order the complete book from the publisher Booklocker.com http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/9098.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. Manchester United - Ramblings of a Nostalgic Old Red Thomas Clare Copyright © 2017 Thomas Clare ISBN: 978-1-63492-170-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Published by BookLocker.com, Inc., St. Petersburg, Florida. Printed on acid-free paper. BookLocker.com, Inc. 2017 First Edition Contents Introduction ........................................................................................ 1 In the Beginning – The Man Who Founded Newton Heath (L&YR) FC ................................................................................... 3 The Brick Builders ........................................................................... 11 So Are the Good Old Days Nothing More Than… ........................... 16 “I Suppose It’s All Changed Now?” .................................................. 21 Sir Matt and Sir Alex - The Wonder of Two ..................................... 25 The Game That I Love Has Lost Its Soul ........................................ 49 Reminiscing Again! ......................................................................... -

Voetbalreisgids Manchester United

Voetbalreisgids Manchester United Ga voorbereid op reis naar Manchester United en haal het maximale uit uw voetbalweekend! Informatie over VoetbalreizenXL, Manchester United, de reis met praktische informatie en de stad Manchester. 0 Inhoudsopgave Over VoetbalreizenXL .............................................................................................................................. 2 De Club .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Manchester United .............................................................................................................................. 3 Stadioninfo .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Zitplaatsen ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Hoe bij het stadion te komen? ............................................................................................................ 5 Wat te doen voor de wedstrijd? ......................................................................................................... 5 De Reis ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 Praktische informatie ......................................................................................................................... -

Date: 11 February 2012 Opposition: Manchester United

Date: 11 February 2012 Guardian Times Sun Independent Sun Telegraph Sunday Mirror February 11 2012 Opposition: Manchester United Echo Independent Telegraph Mirror MEN Sunday Times Observer Sunday Mail Competition: League Evans insists title is all that matters Amid the sound and fury, Manchester United dispatch Liverpool in style Manchester Utd 2 It is almost impossible but look beyond the handshakes, the fury, the tunnel bust- Rooney 47, 50 up, the provocative celebration, one manager's enraged comments and another's Liverpool 1 embarrassment and one might spot that this was not about a victory for Patrice Suarez 80 Evra. It was a day when Manchester United returned to the Premier Referee: P Dowd Attendance: 74,844 League summit with something approaching the style and authority they were It was, of course, hard to escape the feeling at the final whistle at Old Trafford on supposed to have lost. They have bigger fights to win than a poisoned dispute Saturday that Patrice Evra was determined to rub Luis Suarez's nose in it with a with Luis Súarez and Liverpool. victory dance that might have caused even Gary Neville to blush. This was a case "Patrice is a great lad. He gets on with everyone and everyone loves him. I don't of going OTT at OT, if you will, but while such provocative celebrating may yet think it was a case of doing it for Patrice, though," said Jonny Evans, the United land Evra in trouble with the FA -- as it did Neville six years earlier -- it was defender. "It was doing it for what the whole club has been through and nonetheless easy to understand the fervour with which Manchester United especially because of the rivalry and, of course, we wanted to be top of the embraced victory over their bitter rivals. -

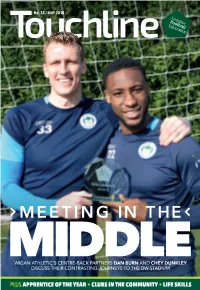

Plus Apprentice of the Year • Clubs in the Community • Life

No. 35 / MAY 2018 WIGAN ATHLETIC’S CENTRE-BACK PARTNERS DAN BURN AND CHEY DUNKLEY DISCUSS THEIR CONTRASTING JOURNEYS TO THE DW STADIUM PLUS APPRENTICE OF THE YEAR • CLUBS IN THE COMMUNITY •Touchline LIFE SKILLSMay 2018 1 Welcome to brought to you by League Football Education No. 35 / MAY 2018 WRITTEN BY JACK WYLIE | DESIGN BY ICG Pass4Soccer Trial Assessment Pass4Soccer, LFE’s official partner Trials 2018 for helping former apprentices earn soccer scholarships in the TUESDAY 8TH MAY 2018 Players have the chance to USA, are hosting a trial game for FA Youth Cup showcase their talents in front Bury FC, players on Friday 11 May. Gigg Lane of scouts from professional The story so far... clubs, non-league clubs The event will take place at Walton From an October trip to Valley Parade to and Universities in the UK Casuals FC, with a large selection an April evening at the Emirates Stadium, and abroad at LFE’s annual of University soccer coaches Blackpool have enjoyed an unforgettable Assessment Trials. searching for new recruits for their squads for next season. journey to the last four of the FA Youth Cup. The events are open to those who are coming to the end of For more information on how to WEDNESDAY 9TH MAY 2018 their apprenticeship or the end of register, give Pass4Soccer a call The young Seasiders recorded five away wins “It was a great goal for me. I just remember being really Nuneaton Town FC, a first professional contract (Under on 0191 229 5236. Liberty Way Stadium along the way to the semi-finals and overcame focused and I think we were all just determined to make 19 year) with the aim of helping three Under-18 Premier League sides – West Ham the most of the opportunity.