1 Introduction: the Global Football League 2 the Network League

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Etoth Dissertation Corrected.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School The College of Arts and Architecture FROM ACTIVISM TO KIETISM: MODERIST SPACES I HUGARIA ART, 1918-1930 BUDAPEST – VIEA – BERLI A Dissertation in Art History by Edit Tóth © 2010 Edit Tóth Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 The dissertation of Edit Tóth was reviewed and approved* by the following: Nancy Locke Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Head of the Department of Art History Michael Bernhard Associate Professor of Political Science *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT From Activism to Kinetism: Modernist Spaces in Hungarian Art, 1918-1930. Budapest – Vienna – Berlin investigates modernist art created in Central Europe of that period, as it responded to the shock effects of modernity. In this endeavor it takes artists directly or indirectly associated with the MA (“Today,” 1916-1925) Hungarian artistic and literary circle and periodical as paradigmatic of this response. From the loose association of artists and literary men, connected more by their ideas than by a distinct style, I single out works by Lajos Kassák – writer, poet, artist, editor, and the main mover and guiding star of MA , – the painter Sándor Bortnyik, the polymath László Moholy- Nagy, and the designer Marcel Breuer. This exclusive selection is based on a particular agenda. First, it considers how the failure of a revolutionary reorganization of society during the Hungarian Soviet Republic (April 23 – August 1, 1919) at the end of World War I prompted the Hungarian Activists to reassess their lofty political ideals in exile and make compromises if they wanted to remain in the vanguard of modernity. -

Theory of the Beautiful Game: the Unification of European Football

Scottish Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 54, No. 3, July 2007 r 2007 The Author Journal compilation r 2007 Scottish Economic Society. Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main St, Malden, MA, 02148, USA THEORY OF THE BEAUTIFUL GAME: THE UNIFICATION OF EUROPEAN FOOTBALL John Vroomann Abstract European football is in a spiral of intra-league and inter-league polarization of talent and wealth. The invariance proposition is revisited with adaptations for win- maximizing sportsman owners facing an uncertain Champions League prize. Sportsman and champion effects have driven European football clubs to the edge of insolvency and polarized competition throughout Europe. Revenue revolutions and financial crises of the Big Five leagues are examined and estimates of competitive balance are compared. The European Super League completes the open-market solution after Bosman. A 30-team Super League is proposed based on the National Football League. In football everything is complicated by the presence of the opposite team. FSartre I Introduction The beauty of the world’s game of football lies in the dynamic balance of symbiotic competition. Since the English Premier League (EPL) broke away from the Football League in 1992, the EPL has effectively lost its competitive balance. The rebellion of the EPL coincided with a deeper media revolution as digital and pay-per-view technologies were delivered by satellite platform into the commercial television vacuum created by public television monopolies throughout Europe. EPL broadcast revenues have exploded 40-fold from h22 million in 1992 to h862 million in 2005 (33% CAGR). -

Walking and Cycling Connectivity Study West Blackburn

WALKING & CYCLING CONNECTIVITY STUDY WEST BLACKBURN June 2020 CONTENT: 1.0 Overview 2.0 Baseline Study 3.0 Detailed Trip Study 4.0 Route Appraisal and Ratings 5.0 Suggested Improvements & Conclusions 1.0 OVERVIEW West Blackburn 1.0 Introduction Capita has been appointed by Blackburn with Darwen expected to deliver up to 110 dwellings); pedestrian and cycle movement within the area. Borough Council (BwDBC) to prepare a connectivity • Pleasington Lakes (approximately 46.2 Ha of study to appraise the potential impact of development developable land, expected to deliver up to 450 Study Area sites on the local pedestrian network. dwellings;) • Eclipse Mill site in Feniscowles, expected to deliver The study area is outlined on the plan opposite. In This study will consider the implications arising 52 dwellings; general, the area comprises the land encompassed from the build-out of new proposed housing sites • Tower Road site in Cherry Tree, expected to deliver by the West Blackburn Growth Zone. The study area for pedestrian travel, in order to identify potential approximately 30 dwellings. principally consists of the area bounded by Livesey gaps in the existing highway and sustainable travel Branch Road to the north, A666 Bolton Road to the provision. It will also consider potential options for east, the M65 to the south, and Preston Old Road and The study also takes into account the committed any improvements which may be necessary in order to the Blackburn with Darwen Borough Boundary to the improvements that were delivered as part of the adequately support the developments. west Pennine Reach scheme. This project was completed in April 2017 to create new bus rapid transit corridors Findings will also be used to inform the Local Plan which will reduce bus journey times and improve the Review currently underway that will identify growth reliability of services. -

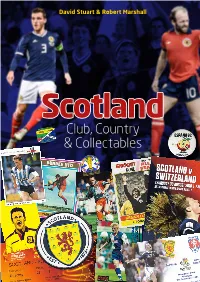

Sample Download

David Stuart & RobertScotland: Club, Marshall Country & Collectables Club, Country & Collectables 1 Scotland Club, Country & Collectables David Stuart & Robert Marshall Pitch Publishing Ltd A2 Yeoman Gate Yeoman Way Durrington BN13 3QZ Email: [email protected] Web: www.pitchpublishing.co.uk First published by Pitch Publishing 2019 Text © 2019 Robert Marshall and David Stuart Robert Marshall and David Stuart have asserted their rights in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the authors of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher and the copyright owners, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the terms stated here should be sent to the publishers at the UK address printed on this page. The publisher makes no representation, express or implied, with regard to the accuracy of the information contained in this book and cannot accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 13-digit ISBN: 9781785315419 Design and typesetting by Olner Pro Sport Media. Printed in India by Replika Press Scotland: Club, Country & Collectables INTRODUCTION Just when you thought it was safe again to and Don Hutchison, the match go back inside a quality bookshop, along badges (stinking or otherwise), comes another offbeat soccer hardback (or the Caribbean postage stamps football annual for grown-ups) from David ‘deifying’ Scotland World Cup Stuart and Robert Marshall, Scottish football squads and the replica strips which writing’s answer to Ernest Hemingway and just defy belief! There’s no limit Mary Shelley. -

Sport-Led Urban Development Strategies: an Analysis of Changes in Built Area, Land Use Patterns, and Assessed Values Around 15 Major League Arenas

Sport-led Urban Development Strategies: An Analysis of Changes in Built Area, Land Use Patterns, and Assessed Values Around 15 Major League Arenas By Stephanie F. Gerretsen A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sport Management) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Mark Rosentraub, Chair Professor Rodney Fort Assistant Professor Ana Paula Pimentel-Walker Associate Professor David Swindell, Arizona State University Stephanie F. Gerretsen [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-4934-0386 © Stephanie F. Gerretsen 2018 Table of Contents List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. xi List of Figures ............................................................................................................................. xvii List of Appendices ..................................................................................................................... xxiv Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... xxv CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 1.1 CITIES, ARENAS, AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT ........................................................................ 1 1.1.1 The Cost of Arena-led Strategies: Public Subsidies for Major League Arenas ............ -

Reach PLC Summary Response to the Digital Markets Taskforce Call for Evidence

Reach PLC summary response to the Digital Markets Taskforce call for evidence Introduction Reach PLC is the largest national and regional news publisher in the UK, with influential and iconic brands such as the Daily Mirror, Daily Express, Sunday People, Daily Record, Daily Star, OK! and market leading regional titles including the Manchester Evening News, Liverpool Echo, Birmingham Mail and Bristol Post. Our network of over 70 websites provides 24/7 coverage of news, sport and showbiz stories, with over one billion views every month. Last year we sold 620 million newspapers, and we over 41 million people every month visit our websites – more than any other newspaper publisher in the UK. Changes to the Reach business Earlier this month we announced changes to the structure of our organisation to protect our news titles. This included plans to reduce our workforce from its current level of 4,700 by around 550 roles, gearing our cost base to the new market conditions resulting from the pandemic. These plans are still in consultation but are likely to result in the loss of over 300 journalist roles within the Reach business across national, regional and local titles. Reach accepts that consumers will continue to shift to its digital products, and digital growth is central to our future strategy. However, our ability to monetise our leading audience is significantly impacted by the domination of the advertising market by the leading tech platforms. Moreover, as a publisher of scale with a presence across national, regional and local markets, we have an ability to adapt and achieve efficiencies in the new market conditions that smaller local publishers do not. -

Sheet1 Page 1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen

Sheet1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen - Press & Journal 71,044 Dundee Courier & Advertiser 61,981 Norwich - Eastern Daily Press 59,490 Belfast Telegraph 59,319 Shropshire Star 55,606 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Evening Chronicle 52,486 Glasgow - Evening Times 52,400 Leicester Mercury 51,150 The Sentinel 50,792 Aberdeen - Evening Express 47,849 Birmingham Mail 47,217 Irish News - Morning 43,647 Hull Daily Mail 43,523 Portsmouth - News & Sports Mail 41,442 Darlington - The Northern Echo 41,181 Teesside - Evening Gazette 40,546 South Wales Evening Post 40,149 Edinburgh - Evening News 39,947 Leeds - Yorkshire Post 39,698 Bristol Evening Post 38,344 Sheffield Star & Green 'Un 37,255 Leeds - Yorkshire Evening Post 36,512 Nottingham Post 35,361 Coventry Telegraph 34,359 Sunderland Echo & Football Echo 32,771 Cardiff - South Wales Echo - Evening 32,754 Derby Telegraph 32,356 Southampton - Southern Daily Echo 31,964 Daily Post (Wales) 31,802 Plymouth - Western Morning News 31,058 Southend - Basildon - Castle Point - Echo 30,108 Ipswich - East Anglian Daily Times 29,932 Plymouth - The Herald 29,709 Bristol - Western Daily Press 28,322 Wales - The Western Mail - Morning 26,931 Bournemouth - The Daily Echo 26,818 Bradford - Telegraph & Argus 26,766 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Journal 26,280 York - The Press 25,989 Grimsby Telegraph 25,974 The Argus Brighton 24,949 Dundee Evening Telegraph 23,631 Ulster - News Letter 23,492 South Wales Argus - Evening 23,332 Lancashire Telegraph - Blackburn 23,260 -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1959-03-03

,......, .. Report On SUI Presiclent VI,.II M. H~ rejlOrts on the pad y .... at SUI in a ..... rt Mriu .... Inni ... hi- 01 owon day on pa.. t. Serving The State University of Iowa and the People of Iowa City Five Cents a CIIPY Iowa city, towa. TUeSiGy. March 3. 1959 I Pro es aste oonwar ,• • • ata I'te Igna S n oar it Play Written Just To Provide Successful Belly Laughs: Author Sederholm Cape Firing By KAY KRESS associate prof sor or dramatic art. Staff Wrlt.r who is directing "Beyond Our Con· trol," ha added physical move· At Midnight " 'Beyond Our Control,' said its TINV TUBES WITH BIG RESPONSIBILITIES-Sil. or .pecl.lly sm.ller count,,. is enc.sed in le.d. to hllp scl.ntlsts to det.rmlne m nt lind slaging which add to how much shieldin, will be needed to pr.vl... .ar. P.... II. fer ~uthor, Fred Sederholm, "was writ the com dy effect. constructed lI.illlt' counters .board Pion", IV Is dr.matically ten simply to provide an audience All Four Stages Indinled by pencil .Iong side. Within the moon,sun probe th. the first m.n in sp.ce.-Ooily lowon Pheto, with several hours of belly Sed rholm aid he con Iders a Ignite Okay laughter." farce the mo t diCCicult to act be· cau e an actor can never "feel" II By JIM DAVIS "The play," he continued, "mere· comedy part. He must depend up· St.ff Write,. * * * ly presents a series oC, (! hope), on technique and concentrate on humorous incidents involving a 1300-Pound delivering lin . -

Gender in Televised Sports: News and Highlight Shows, 1989-2009

GENDER IN TELEVISED SPORTS NEWS AND HIGHLIGHTS SHOWS, 1989‐2009 CO‐INVESTIGATORS Michael A. Messner, Ph.D. University of Southern California Cheryl Cooky, Ph.D. Purdue University RESEARCH ASSISTANT Robin Hextrum University of Southern California With an Introduction by Diana Nyad Center for Feminist Research, University of Southern California June, 2010 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION by Diana Nyad…………………………………………………………………….………..3 II. SUMMARY OF FINDINGS…………………………………………………………………………………………4 III. DESCRIPTION OF STUDY…………………………………………………………………………………………6 IV. DESCRIPTION OF FINDINGS……………………………………………………………………………………8 1. Sports news: Coverage of women’s sports plummets 2. ESPN SportsCenter: A decline in coverage of women’s sports 3. Ticker Time: Women’s sports on the margins 4. Men’s “Big Three” sports are the central focus 5. Unequal coverage of women’s and men’s pro and college basketball 6. Shifting portrayals of women 7. Commentators: Racially diverse; Sex‐segregated V. ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION OF FINDINGS…………………………………………………….22 VI. REFERENCES……………………………………………………………………………………..…………………28 VII. APPENDIX: SELECTED WOMEN’S SPORTING EVENTS DURING THE STUDY…………..30 VIII. BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE OF THE STUDY………………………………….…………….….33 IX. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………………………………….34 X. ABOUT THE CO‐INVESTIGATORS………………………………………………………………..….…….35 2 I. INTRODUCTION By Diana Nyad For two decades, the GENDER IN TELEVISED SPORTS report has tracked the progress— as well as the lack of progress—in the coverage of women’s sports on television news and highlights shows. One of the positive outcomes derived from past editions of this valuable study has been a notable improvement in the often‐derogatory ways that sports commentators used to routinely speak of women athletes. The good news in this report is that there is far less insulting and overtly sexist treatment of women athletes than there was twenty or even ten years ago. -

A Study of Institutional Racism in Football

THE BALL IS FLAT THE BALL IS FLAT: A STUDY OF INSTITUTIONAL RACISM IN FOOTBALL By ERIC POOL, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Eric Pool, September 2010 MASTER OF ARTS (2010) McMaster University (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Ball is Flat: A Study ofInstitutional Racism in Football AUTHOR: Eric Pool, B.A. (University of Waterloo) SUPERVISOR: Professor Chandrima Chakraborty NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 127 ii Abstract: This project examines the ways in which the global mobility of players has unsettled the traditional nationalistic structure of football and the anxious responses by specific football institutions as they struggle to protect their respective political and economic hegemonies over the game. My intention is to expose the recent institutional exploitation of football's "cultural power" (Stoddart, Cultural Imperialism 650) and ability to impassion and mobilize the masses in order to maintain traditional concepts of authority and identity. The first chapter of this project will interrogate the exclusionary selection practices of both the Mexican and the English Football Associations. Both institutions promote ethnoracially singular understandings of national identity as a means of escaping disparaging accusations of "artificiality," thereby protecting the purity and prestige of the nation, as well as the profitability of the national brand. The next chapter will then turn its attention to FIFA's proposed 6+5 policy, arguing that the rule is an institutional effort by FIF A to constrain and control the traditional structure of football in order to preserve the profitability of its highly "mediated and commodified spectacle" (Sugden and Tomlinson, Contest 231) as well as assert its authority and autonomy in the global realm. -

1 FC UNITED LIMITED Trading As FC United of Manchester NOTICE of An

FC UNITED LIMITED Trading as FC United of Manchester NOTICE of an extraordinary General Meeting NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that an extraordinary General Meeting of FC United Limited will take place on Saturday 25th June 2016, at Longfield Suite, 3 Longfield Centre, Prestwich M25 1AY. The meeting will commence at noon. Registration opens at 11.00am. The meeting will consider the following business: 1. Chair’s Welcome and Election of Scrutineers 2. Questions for candidates Re-Open Nominations Members who feel that some or all candidates are unsuitable may indicate this by voting to re-open nominations. Lawrence Gill This nomination is supported by Blaine Emmett, Nick Duckett, Alex Jones, Peter Wharton, Robin Squelch. I’m Lawrence Gill, co-owner, founder member and season ticket holder since 2005. Prior to that I was a season ticket holder and shareholder at OT. As FC we have achieved so much in a short space of time. However, that progress has not been without its difficulties and the last twelve months have been difficult. I think it’s inevitable that, given our roots as a bunch of ‘arsey’, opinionated Mancunians, we have differing opinions on how we see progress to date and what should happen next. Consensus isn’t always achievable. But we are a democratic organisation and that brings a responsibility on all of us to listen to the opinions of others in a respectful way and decide as a majority on the way forward. I think we have scored a few own goals over the past few months. As members, we rely on communication from the club. -

International Presentations & Masters Football Coaching

International Presentations & Masters Football Coaching: Switzerland, Germany, England, Denmark, France, Belgium, Italy, Qatar, Oman, Wales, USA, Guernsey, Jersey, Gibraltar, Portugal, Spain, Turkey, Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, Canada: Switzerland Hubball, H.T. (2019). Sustained Participation in a Grassroots International Masters 5-a- side/Futsal World Cup Football Tournament (2006-2022); Performance Analysis in Advanced- level 55+ Football: Small-sided Game Competition. Invited presentation, FIFA (Fédération Internationale de Football Association), Zurich, September. Hubball, H.T. (2008). The International Super Masters 5-a-side/Futsal World Cup Football Tournament: Evolution & Sustainability. Keynote Address, 2008 International Masters World Cup, PE University of Zurich, Filzbach, May. Hubball, H.T. (2008). Masters/Veterans Soccer Communities: Local and Global Contexts. Feature research poster, International Symposium, Filzbach, Switzerland. Germany Hubball, H.T. (2019). Sustained Participation in a Grassroots International Masters 5-a- side/Futsal World Cup Football Tournament (2006-2022); Performance Analysis in Advanced- level 55+ Football: Small-sided Game Competition. Invited presentation, Bavarian Football Association, Munich, September. Hubball, H.T. (2012). Super Masters/Veterans 5-a-side Futsal World Cup Tournament: From Youth to Masters Team and Player Development in a Canadian Futsal Academy Program. Campus-wide presentation, German Sport University, Cologne, Germany, April. Denmark Hubball, H.T. (2019). Hosting the International Super Masters 5-a-side/Futsal World Cup Football Tournaments (2006-2022). Invited Presentation to the Executive Board of the Akademisk Boldklub FC, Denmark, May. Hubball, H.T., & Reddy. P (2015). Impact of walking football: Effective team strategies for high performance veteran players. 8th World Congress on Science and Football, Copenhagen, Denmark, May. France Hubball, H.T.