1 DIFFERENCES : on the Lapidary Style. Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Course Outline for This Program

Program Outline 434- Jewellery and Metalwork NUNAVUT INUIT LANGUAGES AND CULTURES Jewelry and Metalwork (and all fine arts) PROGRAM REPORT 434 Jewellery and Metalwork Start Term: No Specified End Date End Term: No Specified End Date Program Status: Approved Action Type: N/A Change Type: N/A Discontinued: No Latest Version: Yes Printed: 03/30/2015 1 Program Outline 434- Jewellery and Metalwork Program Details 434 - Jewellery and Metalwork Start Term: No Specified End Date End Term: No Specified End Date Program Details Code 434 Title Jewellery and Metalwork Start Term No Specified End Date End Term No Specified End Date Total Credits Institution Nunavut Faculty Inuit Languages and Cultures Department Jewelry and Metalwork (and all fine arts) General Information Eligible for RPL No Description The Program in Jewellery and Metalwork will enable students to develop their knowledge and skills of jewellery and metalwork production in a professional studio atmosphere. To this end the program stresses high standards of craftship and creativity, all the time encouraging and exposing students to a wide range of materials, techniques and concepts. This program is designed to allow the individual student to specialize in an area of study of particular interest. There is an emphasis on creative thinking and problem-solving throughout the program.The first year of the program provides an environment for the students to acquire the necessary skills that will enable them to translate their ideas into two and three dimensional jewellery and metalwork. This first year includes courses in: Drawing and Design, Inuit Art and Jewellery History, Lapidary and also Business and Communications. -

Lapidary Journal Jewelry Artist March 2012

INDEX TO VOLUME 65 Lapidary Journal Jewelry Artist April 2011-March 2012 INDEX BY FEATURE/ Signature Techniques Part 1 Resin Earrings and Pendant, PROJECT/DEPARTMENT of 2, 20, 09/10-11 30, 08-11 Signature Techniques Part 2 Sagenite Intarsia Pendant, 50, With title, page number, of 2, 18, 11-11 04-11 month, and year published Special Event Sales, 22, 08-11 Silver Clay and Wire Ring, 58, When to Saw Your Rough, 74, 03-12 FEATURE ARTICLES Smokin’*, 43, 09/10-11 01/02-12 Argentium® Tips, 50, 03-12 Spinwheel, 20, 08-11 Arizona Opal, 22, 01/02-12 PROJECTS/DEMOS/FACET Stacking Ring Trio, 74, Basic Files, 36, 11-11 05/06-11 DESIGNS Brachiopod Agate, 26, 04-11 Sterling Safety Pin, 22, 12-11 Alabaster Bowls, 54, 07-11 Create Your Best Workspace, Swirl Step Cut Revisited, 72, Amethyst Crystal Cross, 34, 28, 11-11 01/02-12 Cut Together, 66, 01/02-12 12-11 Tabbed Fossil Coral Pendant, Deciphering Chinese Writing Copper and Silver Clay 50, 01/02-12 Linked Bracelet, 48, 07-11 12, 07-11 Stone, 78, 01/02-12 Torch Fired Enamel Medallion Site of Your Own, A, 12, 03-12 Easier Torchwork, 43, 11-11 Copper Wire Cuff with Silver Necklace, 33, 09/10-11 Elizabeth Taylor’s Legendary Wire “Inlay,” 28, 07-11 Trillion Diamonds Barion, 44, SMOKIN’ STONES Jewels, 58, 12-11 Coquina Pendant, 44, 05/06-11 Alabaster, 52, 07-11 Ethiopian Opal, 28, 01/02-12 01/02-12 Turquoise and Pierced Silver Ametrine, 44, 09/10-11 Find the Right Findings, 46, Corrugated Copper Pendant, Bead Bracelet – Plus!, 44, Coquina, 42, 01/02-12 09/10-11 24, 05/06-11 04-11 Fossilized Ivory, 24, 04-11 -

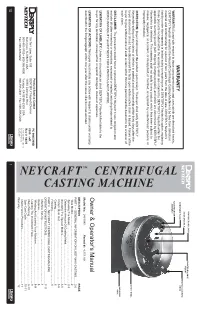

Neycraft Centrifugal Casting Machine to Be Free from Defects in Material and Workmanship for a Period of Two Years from the Date of Sale

CRUCIBLE SLIDE LEVER COUNTER BALANCE WEIGHT SILICA CRUCIBLE WINDING & LOCKING WARRANTY INVESTMENT FLASK KNOB FLASK RECEIVER WARRANTY: Except with respect to those components parts and uses which are described herein, ASSEMBLY DENTSPLY Neytech warrants the Neycraft Centrifugal Casting Machine to be free from defects in material and workmanship for a period of two years from the date of sale. DENTSPLY Neytech’s liability under this warranty is limited solely to repairing or, at DENTSPLY Neytech’s option, replacing those products included within the warranty which are returned to DENTSPLY Neytech within the applicable warranty period (with shipping charges prepaid), and which are determined by DENTSPLY Neytech to be defective. This warranty shall not apply to any product which has been subject to misuse; negligence; or accident; or misapplied; or modified; or repaired by unauthorized persons; or improperly installed. INSPECTION: Buyer shall inspect the product upon receipt. The buyer shall notify DENTSPLY Neytech in writing of any claims of defects in material and workmanship within thirty days after the buyer discovers or should have discovered the facts upon which such a claim is based. Failure of the SAFETY SHELL buyer to give written notice of such a claim within this time period shall be deemed to be a waiver of such claim. MOUNTING BASE DISCLAIMER: The provisions stated herein represent DENTSPLY Neytech’s sole obligation and exclude all other remedies or warranties, expressed or implied, including those related to MERCHANTABILITY and FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. LIMITATION OF LIABILITY: Under no circumstances shall DENTSPLY Neytech be liable to the buyer for any incidental, consequential or special damages, losses or expenses. -

METAL ENAMELING Leader Guide Pub

Arts & Communication METAL ENAMELING Leader Guide Pub. No. CIR009 WISCONSIN 4-H PUBLICATION HEAD HEART HANDS HEALTH Contents Before Each Meeting: Checklist ..............................1 Adhesive Agents or Binders ....................................6 Facilities Tools, Materials and Equipment Safety Precautions..................................................6 Resource Materials Kiln Firing and Table-Top Units Expenses Metal Cutting and Cleaning Planning Application of Enamel Colors Youth Leaders Other Cautions Project Meeting: Checklist ......................................3 Metal Art and Jewery Terms ...................................7 Purposes of 4-H Arts and Crafts ...........................................8 Components of Good Metal Enameling Futher Leader Training Sources of Supplies How to Start Working Prepare a Project Plan Bibiography ............................................................8 Evaluation of Projects Kiln Prearation and Maintenance ...........................6 WISCONSIN 4-H Pub. No. CIR009, Pg. Welcome! Be sure all youth are familiar with 4H158, Metal Enameling As a leader in the 4-H Metal Enameling Project, you only Member Guide. The guide suggests some tools (soldering need an interest in young people and metal enameling to be irons and propane torches), materials and methods which are successful. more appropriate for older youth and more suitable for larger facilities (school art room or spacious county center), rather To get started, contact your county University of Wisconsin- than your kitchen or basement. Rearrange these recommen- Extension office for the 4-H leadership booklets 4H350, dations to best suit the ages and abilities of your group’s Getting Started in 4-H Leadership, and 4H500, I’m a 4-H membership and your own comfort level as helper. Project Leader. Now What Do I Do? (also available on the Wisconsin 4-H Web Site at http://www.uwex.edu/ces/4h/ As in any art project, a generous supply of tools and pubs/index.html). -

Studio Member Magazine of the PMC Guild PMC

Studio Member Magazine of the PMC Guild PMC Summer 2005 · Volume 8, Number 2 Studio Summer 2005 · Volume 8, Number 2 Member Magazine of the PMC Guild PMC On the Cover: Gang blade from PMC Tool and Supply/Darway features Design Studio, leaf cutters and rolling tool from Celie Fago, and tool kit from New Mexico Clay. Background image is Elaine Luther working on her butterfly pendant... see page 7 4 Word Art Studio PMC This beginner's project by Debbie Fehrenbach using rubber stamps is PMC Guild ideal for teaching the technique. P.O. Box 265, Mansfield, MA 02048 www.PMCguild.com 6 Butterfly Inlay Pendant Volume 8, Number 2 • Summer 2005 Editor—Suzanne Wade Elaine Luther demonstrates the use of some of her favorite tools Technical Editor—Tim McCreight in this pendant project. Art Director—Jonah Spivak Advertising Manager—Bill Spilman Studio PMC is published by the PMC Guild Inc. 10 The Tool Trade • How to SUBMIT WORK to Studio PMC… For some PMC artists, developing and selling tools has become We welcome your PMC photos, articles and ideas. You may submit by mail or electronically. Please include your name, address, e-mail, a welcome addition to their PMC careers. phone, plus a full description of your PMC piece and a brief bio. Slides are preferred, but color prints and digital images are OK. By Mail: Mail articles and photos to: Studio PMC, 11 Tools, Tools, Tools P.O. Box 265, Mansfield, MA 02048. Electronically: E-mail articles in the body of the e-mail, or as Studio PMC's First Tool Buyers' Guide! A treasure trove of tools attachments. -

JMD How to Enamel Jewelry

PRESENTS How to Enamel Jewelry: Expert Enameling Tips, Tools, and Techniques Jewelry Making Daily presents How to Enamel Jewelry: Expert Enameling Tips, Tools, and Techniques 7 3 21 ENAMELING TIPS BY HELEN I. DRIGGS 12 10 TORCH FIRED ENAMEL ENAMELING MEDALLION NECKLACE BY HELEN I. DRIGGS BY HELEN I. DRIGGS ENAMELED FILIGREE BEADS BY PAM EAST I LOVE COLOR! In jewelry making, enamel is one of the most In “Enameled Filigree Beads,” Pam East walks you through a versatile sources of pure, luscious color – powdered glass you simple technique of torch firing enamel onto a premade bead can apply with great precision onto silver, gold, copper, and using a handheld butane torch instead of an enameling kiln. other jewelry metals. With enamels, you can paint with a broad The enamel adds color to the bead, while the silver filigree brush or add minute and elaborate detail to pendants, brace- creates the look of delicate cells like those in cloisonné enamel lets, earrings, and more. You can work in rich, saturated tones work. And in “Torch Fired Enamel Medallion Necklace,” Helen or in the subtlest of pastels. You can create a world of sharp Driggs shows you how to create your own torch fired enamel contrast in black and white or one entirely of shades of gray. “cabochons,” how to tab set those cabs, and how to stamp You can even mimic the colors of the finest gemstones, but you and patinate the surrounding metalwork, which you can put can also produce hues and patterns you’d never find among the together using the chain of your choice. -

Gems'll Quick

c -/9 ARIZONA DEPARTMENT OF MINERAL RESOURCES MINERAL BUILDING, FAIRGROUNDS Phoenix, Arizona 85007 September 6, 1977 BOOK LIST 11 For the beginner, ~ For general information, d/ For the student 11 Advanced text, ~ Technical specialized text Books for the Mineral Collector Author Publisher *Field Guide to Rocks and Minerals d/ Pough Houghton Miffin Mineral Recognition J/ Vanders & Kerr John Wiley Prospecting for Gemstones and Minerals d/ Sinkankas Von Nostrand *A Textbook of Mineralogy 11 Dana John Wiley *The Mineral Kingdom ~ Desautels Grosset & Dunlap *Minerals and Man ~ Hurlbut Random House *Glossary of Mineral Species 11 Michael Fleischer Mineralogical Record, Inc. *Rocks and Minerals 11 Joel Arem Ridge Press, Inc . *Encyclopedia of Minerals ~ Roberts, Rapp Von Nostrand and Weber *Mineralogy of Arizona J/ Anthony-Williams University of, Bideaux Arizona Press Books on Geology Stories Read from Rocks 11 Parker Row Peterson The Earth's Changing Surface 11 Parker Row Peterson Rocks, Rivers & the Changing Earth ~ Schneider W. R. Scott Anatomy of the Earth ~ Cailleux McGraw-Hill Structural Geology 11 De Sitter McGraw-Hill Physical Geology 11 Longwell, et al John Wiley Elements of Geology 11 Zumberge John Wiley *Minerals and Rocks 11 Kirkaldy Hippocrene Books Books on Gems and Gem Cutting Practical Gemmology J/ Webster Wehman Brothers The Story of the Gems 'll Whitlock Emerson The Book of Agates and Other Quartz Gems'll Quick Chi lton Gemstones of North America 11 Si nkankas Von Nostrand Von Nostrand's Standard Catalog of Gems 11 Sinkankas -

The Cultural Significance of Precious Stones in Early Modern England

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History History, Department of 6-2011 The Cultural Significance of Precious Stones in Early Modern England Cassandra Auble University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss Part of the Cultural History Commons, European History Commons, and the History of Gender Commons Auble, Cassandra, "The Cultural Significance of Precious Stones in Early Modern England" (2011). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. 39. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/39 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF PRECIOUS STONES IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND by Cassandra J. Auble A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: History Under the Supervision of Professor Carole Levin Lincoln, Nebraska June, 2011 THE CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF PRECIOUS STONES IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND Cassandra J. Auble, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2011 Adviser: Carole Levin Sixteenth and seventeenth century sources reveal that precious stones served a number of important functions in Elizabethan and early Stuart society. The beauty and rarity of certain precious stones made them ideal additions to fashion and dress of the day. These stones also served political purposes when flaunted as examples of a country‘s wealth, bestowed as favors, or even worn as a show of royal support. -

JD: Jewelry Design

JD: Jewelry Design JD 101 — Introduction to Jewelry JD 115 — Metal Forming Techniques: Fabrication Chasing and Repousse 2 credits; 1 lecture and 2 lab hours 1.5 credits; 3 lab hours Basic processes used in the design and Introduces students to jewelry-forming creation of jewelry. Students fabricate their techniques by making their own dapping own designs in the studio. and chasing tools by means of forging, JD 102 — Enameling Techniques for annealing, and tempering. Using these Precious Metals/Fine Jewelry/Objects tools, objects are created by repousse and D'Art other methods. 2 credits; 1 lecture and 2 lab hours Prerequisite(s): all first-semester Jewelry Vitreous enameling on precious metals. Design courses or approval of chairperson Studies include an emphasis on the "Co-requisite(s): JD 116, JD 122, JD metallurgical properties of gold, silver, and 134, JD 171, and JD 173 or approval of platinum and their chemical compatibility chairperson. with enamels. Surface treatments, ancient JD 117 — Enameling for Contemporary and modern, that intensify the jewel- Jewelry like qualities of vitreous enamel on 2 credits; 1 lecture and 2 lab hours precious metal will be explored. along with Vitreous enamel has been used for construction techniques that help students centuries as a means of adding color transform glass into beautiful, functional and richness to precious objects and jewelry and objects of art. jewelry. This course examines historical Prerequisite(s): JD 101. and contemporary uses of enamel, and JD 103 — Jewelry and Accessories explores the various methods of its Fabrication (Interdisciplinary) application, including cloisonne, limoges 2 credits; 1 lecture and 2 lab hours and champleve, the use of silver and gold This is an interdisciplinary course cross- foils, oxidation, surface finishing and setting listed with LD 103. -

Sapphire from Australia

SAPPHIRES FROM AUSTRALIA By Terrence Coldham During the last 20 years, Australia has ew people realize that Australia is one of the major assumed a major role in the production of F producers of sapphire on the world market today. Yet a blue sapphire. Most of the gem material fine blue Australian sapphire (figure 1)competes favorably comes from alluvial deposits in the Anal<ie with blue sapphire from noted localities such as Sri Lanka, (central Queensland) and New England (northern New South Wales) fields. Mining and virtually all other hues associated with sapphire can be techniques range from hand sieving to found in the Australian fields (figure 2). In fact, in the highly mechanized operations. The rough is author's experience it is probable that 50% by weight of usually sorted at the mine offices and sold the sapphire sold through Thailand, usually represented directly to Thai buyers in the fields. The as originating in Southeast Asia, were actually mined in iron-rich Australian sapphires are predom- Australia. inantly blue (90%),with some yellow, some In spite of the role that Australian sapphire plays in the green, and a very few parti-colored stones. world gem market, surprisingly little has been written The rough stones are commonly heat about this indigenous gem. This article seeks both to de- treated in Thailand to remove the silk. scribe the Australian material and its geologic origins and Whileproduction has been down duringthe to introduce the reader to the techniques used to mine the last two years because of depressed prices combined with higher costs, prospects for material, to heat treat it prior to distribution, and to the future are good. -

2019 – 2020 Catalog

Price MLS $1.00 Minnesota Lapidary Supply “YOUR LAPIDARY SUPPLY GENERAL STORE” America’s Supplier of Quality Lapidary Products FOR OVER 50 YEARS!!!! 2019 – 2020 CATALOG SOME OF THE MANY MANUFACTURES WE STOCK AND REPRESENT: DIAMOND AMERITOOL WHEELS BARRANCA TUMBLERS LAPS DISKS CABKING COMPOUND CALWAY DRILL BITS LOT-O-TUMBLER COVINGTON SAW BLADES DIAMOND PACIFIC DONEGAN OPTICAL The M.L.S. The ROCK STORE WAREHOUSE EASTWIND ESTWING FACETRON FOREDOM GRYPHON HI-TECH DIAMOND ARBORS JOBE KEYSTONE ABRASIVES LAPCRAFT LORTONE MK DIAMOND M. L. S. HOURS Sun. & Mon. ------- Closed MLS Tue. thru Fri. ----- 9:00 am to 5:30 pm (CST) REENTEL Sat. ------------------ 9:00 am to 4:00 pm (CST) ABRASIVES & TRU-SQUARE POLISHES OPEN ALL YEAR LONG!!!! ALL PRICES ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE ANY PRINTING ERRORS ARE SUBJECT TO CORRECTION MLS MLS Trademark Registered - Minnesota Lapidary Supply Minnesota Lapidary Supply 201 N. Rum River Drive Princeton, MN 55371 Ph/Fax: (763) 631-0405 email: [email protected] TOLL FREE ORDER PHONE: (888) 612-3444 WEB SITE: www.lapidarysupplies.com “YOUR LAPIDARY MLS Order Toll Free: (888) 612-3444 GENERAL STORE” Minnesota Lapidary Supply Web Site: www.lapidarysupplies.com To Our Customers: June 08, 2019 As a general overview of the new catalog you will note a much expanded selection of abrasives, carriers and polishes. Also, Lortone has quit making the slab saws they made for many years. [This is truly a great loss – I loved the Panther saw!] This size slabbing saw will be replaced by an equal brand, that being the American made Covington Engineering slab saw. -

Gemstone Technical Training Manual Ministry of Mines, Petroleum and Natural Gas

FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ETHIOPIA GEMSTONE TECHNICAL TRAINING MANUAL MINISTRY OF MINES, PETROLEUM AND NATURAL GAS NOVEMBER 2016 FOREWORD Estelle Levin Limited (ELL) and Sudca Development Consultants (Sudca) developed this training manual for the JSDF Project and the Government of Ethiopia’s Ministry of Mines, Petroleum, and Natural Gas (MOMPNG). It was financed by the World Bank administered JSDF grant for support to improve the economic, social, and environmental sustainability of artisanal miners, with a particular emphasis on empowerment of women. The JSDF Project is coordinated by the Women and Youth Directorate of the MoMPNG. ELL Gemstone Expert Herizo Harimalala Tsiverisoa, authored the report, with contribu- tions from: ELL Training Expert, Dr. Jennifer Hinton ELL Team Lead, Dr. John Tychsen; Sudca Gender Expert, Yimegnushal Takele; Sudca Environmental Expert, Andualem Taye; and ELL Project Manager, Adam Rolfe. The publication of this manual is the product of an extensive participatory research and practical training process, which ran from April to November 2016. An initial needs asses- sment visit (April – May) focussed on the physical infrastructure of lapridary centres in Kambolcha and on lapidary skills of women in Delanta and Wadlain in the Amhara region. This informed the design of draft training materials that were used to deliver a training to cooperatives / Women’s Economic Strengthening Groups and relevant government personnel (June). Feedback from the participants and the client was incorporated into the training material and subsequent design of the training manual. The manual prioritises: • Adult learning techniques that maximise participation and learning-by-doing; and • A Knowledge, Skills and Attitudes (K-S-A) approach to build capacity in techni- cal content while empowering participants by increasing their Knowledge and Skills to create gender-responsive trainers with the Attitudes necessary to support future actions.