Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Brief Description of Item an Important

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Brief Description of Item An important Glasgow School Clock, 1896, designed by Margaret Macdonald (1864-1933) and Frances Macdonald (1871-1921), sponsored by Thomas Ross and Sons. The clock face with repoussé decoration depicting infants clutching at dandelions to signify the passing of time, the weights depicting owls and birds respectively. Silver, white metal and walnut. Clock face: 28.5 x 28 cms Mark of T.R. & S. Glasgow hallmarks for 1896. Condition: Good, the surface slightly rubbed commensurate with use. 2. Context Provenance. Lawrence’s Auctioneers, Crewkerne, Somerset, 6 April 2006, Lot 219, Collection John Jesse, London Christie’s, London, King Street, 3 November, 2015, Lot. 81. References. The Studio, vol.9, 1896, p.204, ill. p.203 The Athenaeum, No.3598, October 1896, p.491 T. Morris, `Concerning the Work of Margaret Macdonald, Frances Macdonald, Charles Mackintosh and Herbert McNair: An Appreciation’, unpublished manuscript, Collection Glasgow Museums, E. 46-5X, 1897, p.5. Dekorative Kunst, vol.3, 1898, ill. p.73 J. Helland, The Studios of Frances and Margaret Macdonald, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1996, p.86. ill. p.85 P. Robertson (ed.), Doves and Dreams, The Art of Frances Macdonald and J. Herbert McNair, Aldershot, Lund Humphries, 2006, p.86, F13, cat. Ill. 3. Exhibited Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society 5th Exhibition, New Gallery, London, 1896 (285). Doves and Dreams, The Art of Frances Macdonald and James Herbert McNair, Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow, 12 August – 18 November 2006, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, 27 January – 22 April 2007. 3. Waverley Criteria The objection to the export of this clock is made under the third Waverley criteria. -

A C C Jj P T Iiid

ACCjJPTiiiD FACULTY OF GRAHUATF qTnn,r?HE "NEW WOMAN" IN FIN-DE-SIECLE ART: tS FRANCES AND MARGARET MACDONALD by 1ATF _______________' i2 Janice Valerie Helland ~ --- ------ B.A., University of Lethbridge, 1973 M.A., University of Victoria, 1984 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY : in the Department of History in Art We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard _________________ Dr. Ej^Tumasonis, Supervisor (Department of History in Art) Dr. J. Osborne, Departmental Member (Department of History in Art) Dr. A. Wel<gj)^*DepartmentaI Member (Department of Histor^in Art) Dr. A. McLa^fen, Outside Member (Department of History) _________________________________________ Dr. A. Fontaine, Outgj.de Member (Department of Biology) ________________________________________ Dr. B./Elliott, External Examiner (University of Alberta) ® JANICE VALERIE HELLAND, 1991 University of Victoria All rights reserved. Thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or other means, without the permission of the author. 11 Supervisor: Dr. E, Turoasonis ABSTRACT Scottish artists Margaret and Frances Macdonald produced their most innovative art during the last decade of the nineteenth century. They received their training at the Glasgow School of Art and became known for their contribution to "the Glasgow Style," Scotland's answer to Continental Art nouveau and Symbolism. Although they inherited their visual vocabulary from the male-dominated language of the fin-de-siècle. they produced representations of women that differed from those made by their male colleagues. I suggest that these representations were informed by the female exper,i*nce and that they must be understood as such if we, as historians, are to discuss their art. -

Frances Macdonald Passing Islands

FRANCES MACDONALD PASSING ISLANDS FRANCES MACDONALD PASSING ISLANDS 4 FEBRUARy – 2 march 2013 16 Dundas Street, Edinburgh EH3 6HZ Tel 0131 558 1200 Email [email protected] Web www.scottish-gallery.co.uk Cover: Late Afternoon – Port na Fraig, Iona (detail) oil on canvas, 30 x 40 ins, 76.25 x 101.5 cms FOREWORD From her studio overlooking the Corryvreckan, Frances Macdonald has a clear view across the Sound of Jura to the north end of the island; to Scarba, the mountains of Mull before the great expanse of the North Atlantic. Having lived at Crinan for 40 years, Macdonald’s painting is based on her intimate understanding of the landscape around her. Her knowledge of sailing informs her of approaching weather patterns, and she captures fleeting Hebridean sunshine alongside the winter squalls with equal immediacy. Peploe and Cadell’s paintings of Iona cast a long shadow in Scottish art history, yet Macdonald has established herself as a worthy heir to the tradition started at the end of the 19th century. Like Peploe and Cadell she finds delight in the juxtaposition of angular rock and white sand. Her use of the palette knife creates a dynamism and animation in each painting. She works her paint across the canvas in angular lines; her assured marks arrived at through careful elimination of aesthetic non-essentials. It is bravura painting, her means perfectly suited to capture the broken skies and raging seas in full force, with rocks transformed into cubistic patterns. For this, her third exhibition at The Scottish Gallery, she has looked at new subject matter: sketching the flora and fauna of the Galapagos where she visited in November, and the South of France where she often visits. -

PDF Download Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Art of the Four

CHARLES RENNIE MACKINTOSH AND THE ART OF THE FOUR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Roger Billcliffe | 304 pages | 26 Oct 2017 | Frances Lincoln Publishers Ltd | 9780711236844 | English | London, United Kingdom Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Art of the Four PDF Book Shopbop Designer Fashion Brands. Then we will provide you with either a return label or specific instructions for mailing the item back. The tearooms have since become synonymous with Mackintosh. This beautiful notebook features peonies and butterflies from the RHS Lindley Library, is printed on We believe in providing our customers with an ultra-speedy service. A S Webdale rated it really liked it Aug 27, Related Articles. New this month: Scandal rocks an elite British boarding school in The Divines. Jane marked it as to-read Nov 21, To ensure a speedy resolution please enclose the following in your correspondence:. Throughout his life, Mackintosh was always more appreciated in Europe than he was in Scotland. Please do not expect anything beyond what is stated in our listings. DPReview Digital Photography. International Priority Shipping. See all condition definitions - opens in a new window or tab. Overview The Glasgow Style is the name given to the work of a group of young designers and architects working in Glasgow from — Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Seller assumes all responsibility for this listing. A dark secret spans several Subsequently renamed in his honour, the Mackintosh building was to become his masterpiece. Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Art of the Four Writer Carol McFarlane marked it as to-read Nov 21, Pamela Robertson. The book's illustrations are large, clear and numerous, including photographs of period as well as reproductions of the artwork. -

Filozofická Fakulta Univerzity Palackého V Olomouci

Filozofická fakulta Univerzity Palackého v Olomouci Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Representations of Ophelia's Death in British Art Bakalářská práce Autor: Štěpánka Bublíková (Anglická - Francouzská filologie) Vedoucí práce: Mgr. David Livingstone Olomouc 2010 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalářskou práci vypracovala samostatně a uvedla úplný seznam citované a použité literatury. V Olomouci dne: 7.5.2010 .......................................................................... 2 I would like to express my thanks to my supervisor Mgr. David Livingstone for his professional help, patience, encouragement and resourceful comments that contributed to the successful completion of my work. I also would like to thank Norma Galley for her kindness, helpfulness and willingness to provide personal information. My thanks also belong to Zuzana Kašpárková, Filip Mravec and Jana Sochorová for their help and encouragement. Last but not the least, my thanks belong to Nathalie Vanfasse, my teacher at the Université de Provence in Aix-en Provence, France, whose stimulating courses of British painting were a great source of inspiration for me. 3 Contents Introduction ......................................................................................... 6 1. Text and its visual representation ............................................ 8 1.1 Images and texts .................................................................................... 8 "Image" definitions ...................................................................................... -

Spring 2018 CELEBRATORY Issue: 150 Years Since the Birth Of

JOURNALISSUE 102 | SPRING 2018 CELEBRATORY ISSUE: 150 yearS SINce THE BIrtH OF CHarleS RENNIE MacKINtoSH, 1868–1928 JOURNAL SPRING 2018 ISSUE 102 3 Welcome Stuart Robertson, Director, Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society 4 Hon President’s Address & Editor’s Note Sir Kenneth Calman & Charlotte Rostek 5 Mackintosh Architecture 1968–2018 Professor Pamela Robertson on future-proofing the protection and promotion of Mackintosh’s built heritage. 9 9 Seeing the Light Liz Davidson gives a progress report on the restoration of The Glasgow School of Art. 12 The Big Box Richard Williams reveals the NTS’s big plans for The Hill House. 14 Mackintosh at the Willow Celia Sinclair shares the latest on the restoration work. 16 Authentic? 14 Michael C. Davis takes a timely look at this topical aspect of building conservation. 19 A Bedroom at Bath Dr Trevor Turpin explores this commission by Mackintosh. 23 An Interview with Roger Billcliffe Stuart Robertson presents Part 1 of his fascinating interview with Roger Billcliffe. 32 The Künstlerpaar: Mackintosh, Macdonald & The Rose Boudoir Dr Robyne Calvert explores love and art in the shared lives of this artistic couple. 23 36 The Mackintosh Novel Karen Grol introduces her biographical novel on Mackintosh. Above, Top: Detail of prototype library bay for GSA. Photo Alan MacAteer Middle: Detail of front signage for 38 Observing Windyhill Mackintosh at the Willow. Ruairidh C. Moir discusses his commission to build a motor garage at Windyhill. Photo Rachel Keenan Photography Bottom: Frances Macdonald, Ill Omen 40 Charles Rennie Mackintosh – Making the Glasgow Style or Girl in the East Wind with Ravens Passing the Moon, 1894, Alison Brown talks about the making of this major exhibition. -

Shaw, Michael (2015) the Fin-De-Siècle Scots Renascence: the Roles of Decadence in the Development of Scottish Cultural Nationalism, C.1880-1914

Shaw, Michael (2015) The fin-de-siècle Scots Renascence: the roles of decadence in the development of Scottish cultural nationalism, c.1880-1914. PhD thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/6395/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Fin-de-Siècle Scots Renascence: The Roles of Decadence in the Development of Scottish Cultural Nationalism, c.1880-1914 Michael Shaw Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Critical Studies College of Arts University of Glasgow May 2015 Abstract This thesis offers a cultural history of the ‗Scots Renascence‘, a revival of Scottish identity and culture between 1880 and 1914, and demonstrates how heavily Scottish cultural nationalism in this period drew from, and was defined by, fin-de-siècle Decadence. Few cultural historians have taken the notion of a Scots Renascence seriously and many literary critics have styled the period as low point in the health of Scottish culture – a narrative which is deeply flawed. -

This Document Is an Extract from Engage 31: the Past in the Present, 2012, Karen Raney (Ed.)

This document is an extract from engage 31: The Past in the Present, 2012, Karen Raney (ed.). London: engage, the National Association for Gallery Education. All contents © The Authors and engage, unless stated otherwise. www.engage.org/journal 78 This is the Time 79 Past, present and future at The Glasgow School of Art Jenny Brownrigg Exhibitions Director, The Glasgow School of Art The Mackintosh Museum, built in 1909, is at the Glamour’, 5 all flicker tantalisingly on the wall, heart of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s masterwork, or can perpetually be captured as media The Glasgow School of Art’s Mackintosh Building. soundbites. Mackintosh himself is omnipresent in With its high level of architectural detail inside and the city and beyond as an easily recognisable style outside, the museum is the antithesis of the ‘white in merchandising and souvenirs. It is even possible cube’. This essay will explore the ways in which the to buy a ‘Mockintosh’ moustache from the GSA contemporary exhibitions programme for the tour shop. gallery space within this iconic building can create a The Mackintosh building has never been emptied critical exchange between past, present and future. of its educational activities to become a museum. For someone standing here in the present moment, In this living, working building with its community the architect and the presence of generations of of students and staff, past, present and future exist staff, students and visitors who have moved together in a continuum. Even the lights that through the building could represent the shadows Mackintosh had made for the centre of the library in Plato’s Cave. -

The Mackintosh House Leaflet

Hunterian Kelvinbridge Art Gallery Subway shop Hillhead Subway The Mackintosh Fraser building café & shop House* Hillhead St nd Byres Road 2 Floor Landing Bedroom Country Surgeon Micro Museum University Avenue Few alterations were made to the stairwell As in the studio-drawing room, two Zoology Museum as a whole except for the introduction of rooms were knocked through to create an UNIVERSITY OF Bus Stops 4, 4a Kelvinhall GLASGOW a new south-facing window at the first L-shaped apartment, decorated in white, Subway The Mackintosh House floor landing. At this upper level, the west with new door, light-fittings and fireplace. Church Street Hunterian Museum Anatomy Hunterian Art Gallery wall was panelled and a plaster panel, The furniture, with its sculptural detailing Bus Stops 2, 3, 77 Museum Du mb Kelvingrove based on a design for the Willow Tea inspired by plant and bird forms, was arto Park n R Rooms, incorporated above. The striped designed in 1900. oad y Kelvin Hall Wa stairway led to an attic studio/bedroom, d a lvin o A e R r us g Ke ho y n le not reconstructed. u S B tr e The Hunterian at e t Kelvin Hall Old Dumbarton Road “The Mackintosh House is superb. Thank you.” Blantyre Steeer Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum D and M Squires, USA Sauchiehall Street The Mackintosh House Gallery Further Information The Mackintosh House Gallery is entered from the second-floor landing. It houses Find out more about the Mackintosh Collection on our other works from the University’s Mackintosh Collection, the most extensive holding of website: www.gla.ac.uk/hunterian/collections Mackintosh’s drawings and designs in the world. -

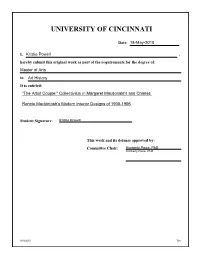

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 18-May-2010 I, Kristie Powell , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in Art History It is entitled: "The Artist Couple:" Collectivism in Margaret Macdonald’s and Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Modern Interior Designs of 1900-1906 Student Signature: Kristie Powell This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Kimberly Paice, PhD Kimberly Paice, PhD 6/18/2010 724 “The Artist Couple:” Collectivism in Margaret Macdonald’s and Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Modern Interior Designs of 1900‐1906 A thesis submitted to The Art History Faculty Of the College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning University of Cincinnati In candidacy for the degree of Masters of Arts in Art History Kristie Powell May 2010 Thesis Chair: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract Margaret Macdonald (1864‐1933) was a Scottish artist and designer whose marriage to the internationally renowned architect and designer, Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868‐1928), has partly obscured the importance of her contributions to art and design. Her collective approach was, in fact, part of what Mackintosh called her "genius," while he considered his own contributions to their projects more akin to "talent or ability." This study is part of the recent scholarship that brings attention to Macdonald’s contributions and crucial roles in collective design work of the modern era. Introducing the study, I evaluate the role of collectivism as it informs Macdonald’s and Mackintosh’s tea‐room designs. Next, I examine the influence of the Arts and Crafts style on the design of the couple’s Mains Street flat home. -

The Sisters of Glasgow Margaret & Frances Macdonald

The Sisters of Glasgow Margaret & Frances Macdonald The Rose Gallery 153 W. Regent St. Glasgow, G2 2R United Kingdom Charles Rennie Mackintosh The group known as ‘The Four’ Keppie, and the sisters were day comprised Charles Rennie students at Glasgow School of Art. Mackintosh, James Herbert McNair They formed an informal creative (1868 - 1955), and the sisters, alliance which produced innovative Margaret Macdonald (1864 - 1933) and at times controversial graphics Frances Macdonald and Frances Macdonald (1873 - and decorative art designs. All four 1921). The artists met as young artists were heavily influenced by students at Glasgow School of Art Aubrey Beardsley and Jan Toorop, in the mid 1890s. Mackintosh and whose work “The Three Brides” McNair were close friends and is considered to be of primary fellow apprentice architects in the significance in the development of Glasgow practice of Honeyman and the Glasgow Style. Margaret Macdonald James Herbert McNair Frances Macdonald (1873-1921) Margaret Macdonald (1864-1933) Frances Macdonald’s achievements at Glasgow School of Art where thread them and Tis a long Margaret was one of the most influenced by mysticism, symbol- to her almost every day. These are less well known than those of she met Mackintosh and path which wanders to desire gifted and successful women ism and Celtic imagery. Her early letters are very important, as they her sister, Margaret Macdonald. Herbert McNair. are no doubt a reflection of artists in Scotland at the turn work c.1893-97, belongs to what give an insight into how much he In part this is due to the loss of this. -

The Glasgow School by George Johnson

Glasgow School The Glasgow School By George Johnson he term Glasgow School crops up The Scottish style icon Charles Rennie Tfrequently in the world of antiques and Mackintosh is the best known of the influential interior design. Despite this it is a fact that most group. Mackintosh was born in a Glasgow people would hardly even give it a second tenement in 1868. He was one of eleven siblings, thought in respect of what it means or its so he encountered overcrowding and hardship from cultural significance. I think it is always worth an early age. Being born with a club foot did not investigating the terms that we come across in help matters. A sickly child through his early years antiques and collecting and also to place them in he developed a natural talent and fondness for art some kind of historical context. The learning and drawing. He disagreed with his father who was experience helps in our pursuit of knowledge a superintendent in the Glasgow police force about and this in turn might help us identify that pot what career he should follow. At the age of sixteen of gold in the rainbow of collecting. Mackintosh accepted an apprenticeship with the architect firm of Honeyman and Keppie. Part of the At the end of the nineteenth century Glasgow apprenticeship process called for him to attend had become quite prosperous. With this came a evening classes at the Glasgow School of Art. Here boost to the arts and crafts market in the area. This he met his future wife and fellow member of The Margaret MacDonald and was further fuelled by the founding of the Glasgow Four Margaret MacDonald.