University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Total Work of Art in European Modernism Series Editor: Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Cornell University

The Total Work of Art in European Modernism Series editor: Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Cornell University Signale: Modern German Letters, Cultures, and Thought publishes new English- language books in literary studies, criticism, cultural studies, and intellectual history pertaining to the German-speaking world, as well as translations of im- portant German-language works. Signale construes “modern” in the broadest terms: the series covers topics ranging from the early modern period to the present. Signale books are published under a joint imprint of Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library in electronic and print formats. Please see http://signale.cornell.edu/. The Total Work of Art in European Modernism David Roberts A Signale Book Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library Ithaca, New York Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library gratefully acknowledge the support of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for the publication of this volume. Copyright © 2011 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writ- ing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2011 by Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roberts, David, 1937– The total work of art in European modernism / David Roberts. p. cm. — (Signale : modern German letters, cultures, and thought) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5023-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Modernism (Aesthetics) 2. -

WC-20-04-20-DT-Mackintosh-Slides.Pdf

Aim • I can say who Charles Rennie Mackintosh was and give some information about his work. Success Criteria • StatementI can respond 1 Lorem to the ipsum work dolorof artists sit amet, and designers consectetur by adipiscingdiscussing elit.my thoughts and feelings. • Statement 2 • Sub statement Charles Rennie Mackintosh Charles Rennie Mackintosh was born in Glasgow on 7th June 1868. Charles became an apprentice architect for a company in Glasgow. He enrolled in evening classes at Glasgow School of Art in the 1890s. His talent grew and he won prizes for his work, including an award that allowed him to take a tour of Italy to study the architecture. Charles also met three friends at the School of Art. The group became known as ‘The Four’. They were Charles, James Herbert McNair, and the sisters; Margaret and Frances Macdonald. They produced new art and designs which became known as the ‘Glasgow Style’. In 1899 McNair and Frances Macdonald married. Charles married Margaret Macdonald the following year. Charles Rennie Mackintosh As well as architecture, Mackintosh designed furniture and produced other art work such as posters and water colours. In Fairyland, Watercolour, Scottish Musical Review, Poster The Room de Luxe at The Willow Tearooms, Glasgow 1897 1896 Designed 1903 Photos granted under creative commons licence, wikimedia - attribution Charles Rennie Mackintosh In 1896 he was asked to design a new building for the Glasgow School of Art. He designed Glasgow’s Queen’s Cross Church and the Scotland Street School. Mackintosh also designed two large private houses, 'Windyhill' in Kilmacolm and 'The Hill House' in Helensburgh. -

Discovering Charles Rennie Mackintosh

Discovering Charles Rennie Mackintosh Travel This tour starts and finishes at the Hilton Grosvenor Hotel, Glasgow. 1-9 Grosvenor Terrace, Glasgow, G12 0TA Tel: 0141 339 8811 E-mail: [email protected] Please note that transport to the hotel is not included in the price of the tour. Transport If you are travelling by car: The Hilton Glasgow Grosvenor is located 5 minutes from the M8 motorway and 5 minutes’ walk from Hillhead subway station. The hotel is situated on the corner of the junction between Byres Road and Great Western Road. On arrival, directly after the hotel turn right, into the lane between the Hilton and Waitrose. Stop at the hotel entrance and get a car park ticket from reception. Finally, drive up the ramp of the Waitrose car park on the left, and keep on going until the top level, which is reserved for hotel guests and the residents of the adjoining flats. Parking is £10 per day, payable locally. If you are travelling by train: The nearest subway stop is Hillhead, which is about a 5 minute walk away on Byres Road. Glasgow Central Station is about 15 minutes by taxi to the hotel. Accommodation The Hilton Grosvenor Hotel The Hilton Grosvenor Hotel is a traditional four-star hotel in the vibrant West End area of the city centre. It is ideally situated in close proximity to the array of locations visited during your tour including the Hunterian Gallery and University. Bedrooms are equipped with all necessities to ensure a relaxing and enjoyable visit, including an en-suite bathroom with bath/shower, TV, telephone, Wi-Fi, hairdryer and complimentary tea/coffee making facilities. -

The Architecture of Sir Ernest George and His Partners, C. 1860-1922

The Architecture of Sir Ernest George and His Partners, C. 1860-1922 Volume II Hilary Joyce Grainger Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Ph. D. The University of Leeds Department of Fine Art January 1985 TABLE OF CONTENTS Notes to Chapters 1- 10 432 Bibliography 487 Catalogue of Executed Works 513 432 Notes to the Text Preface 1 Joseph William Gleeson-White, 'Revival of English Domestic Architecture III: The Work of Mr Ernest George', The Studio, 1896 pp. 147-58; 'The Revival of English Domestic Architecture IV: The Work of Mr Ernest George', The Studio, 1896 pp. 27-33 and 'The Revival of English Domestic Architecture V: The Work of Messrs George and Peto', The Studio, 1896 pp. 204-15. 2 Immediately after the dissolution of partnership with Harold Peto on 31 October 1892, George entered partnership with Alfred Yeates, and so at the time of Gleeson-White's articles, the partnership was only four years old. 3 Gleeson-White, 'The Revival of English Architecture III', op. cit., p. 147. 4 Ibid. 5 Sir ReginaldýBlomfield, Richard Norman Shaw, RA, Architect, 1831-1912: A Study (London, 1940). 6 Andrew Saint, Richard Norman Shaw (London, 1976). 7 Harold Faulkner, 'The Creator of 'Modern Queen Anne': The Architecture of Norman Shaw', Country Life, 15 March 1941 pp. 232-35, p. 232. 8 Saint, op. cit., p. 274. 9 Hermann Muthesius, Das Englische Haus (Berlin 1904-05), 3 vols. 10 Hermann Muthesius, Die Englische Bankunst Der Gerenwart (Leipzig. 1900). 11 Hermann Muthesius, The English House, edited by Dennis Sharp, translated by Janet Seligman London, 1979) p. -

Critical Values: the Career of Charles Rennie Mackintosh 1900-2015 Professor Pamela Robertson It Is a Great Pleasure to Be Back

Keynote Speech Strand 4 Critical Values: The Career of Charles Rennie Mackintosh 1900-2015 Professor Pamela Robertson It is a great pleasure to be back in Barcelona for this exciting Congress. I am grateful to the organisers, in particular Lluis Bosch and Mireia Freixa, for the invitation to speak to you today on Mackintosh, and to all those whose hard work has delivered such a successful and stimulating event. The strand this afternoon is research, specifically research in progress. This session invites us to reflect, for a moment, on critical values and critical fortunes. How are reputations and understandings formed? What value systems are they based on? How do they shift, and why? What are the future directions for us as curators, scholars, teachers? What I aim to present briefly today is threefold: an overview of the critical literature and research surrounding the career of Charles Rennie Mackintosh from around 1900 to 2015 (Fig. 1) – in the hope that this case study will provide some parallels with your individual experiences as researchers, whether working with male and/or female subjects; some reflections on the recently launched Mackintosh Architecture research website; and finally some general remarks on future directions for research. What emerges is the significance of context and individuals; the catalyst of curators and exhibitions; the gradual transference of Mackintosh's artistic legacy into the public domain; and, for Mackintosh at least, the central role of one institution, the University of Glasgow. In 1996, Alan Crawford divided Mackintosh's 'life after death' into three phases which comprised Mackintosh and the Architects, the Enthusiasts, and the Market.1 The trajectory of the scholarly presentation of Mackintosh’s work can, I believe, be divided into five broad phases, though of course at times these overlap: 1. -

Discoverscotland's Most Influential

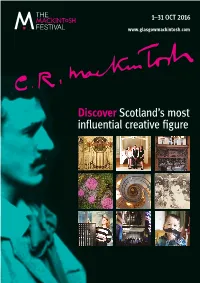

1–31 OCT 2016 www.glasgowmackintosh.com Discover Scotland’s most influential creative figure A Charles Rennie Mackintosh The Mackintosh Festival is organised 1868–1928. by members of Glasgow Mackintosh: Architect. Artist. Designer. Icon. Kelvingrove Art Gallery & Museum The work of the Scottish architect, designer Scotland Street School Museum and artist, Charles Rennie Mackintosh is today The Glasgow School of Art celebrated internationally. Mackintosh was one Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society of the most sophisticated exponents of the House for An Art Lover theory of the room as a work of art, and created The Hunterian distinctive furniture of great formal elegance. In The Hill House Glasgow, you will see the finest examples of his The Lighthouse buildings and interiors and examples of his creative The Glasgow Art Club collaborations with his wife, the accomplished Glasgow Museums Resource Centre (GMRC) artist and designer Margaret Macdonald. Mackintosh Queen’s Cross Special thanks to our partners: GBPT Doors Open Day Glasgow Women’s Library The Willow Tea Rooms The Glad Café Glasgow City Marketing Bureau Glasgow Restaurateurs Association Welcome to the fifth Mackintosh Festival Glasgow Mackintosh is delighted to present another month-long programme of over 40 arts and cultural events to celebrate the life of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Glasgow’s most famous architect, designer and artist. This year we are celebrating House – where you can celebrate installation of Kathy Hinde’s the 2016 Year of Innovation, their 20th birthday with kids -

The Magazine of the Glasgow School of Art Issue 1

Issue 1 The Magazine of The Glasgow School of Art FlOW ISSUE 1 Cover Image: The library corridor, Mackintosh Building, photo: Sharon McPake >BRIEFING Funding increase We√come Research at the GSA has received a welcome cash boost thanks to a rise in Welcome to the first issue of Flow, the magazine of The Glasgow School of Art. funding from the Scottish Higher Education Funding In this issue, Ruth Wishart talks to Professor Seona Reid about the changes and Council (SHEFC).The research challenges ahead for Scotland’s leading art school. This theme is continued by grant has risen from £365,000 to £1.3million, as a result Simon Paterson, GSA Chairman, in his interview Looking to the Future which of the Research Assessment outlines the exciting plans the School has to transform its campus into a Exercise carried out in 2001. world-class learning environment. President’s dinner A dinner to encourage Creating a world-class environment for teaching and research is essential if potential ambassadors for the GSA was held in the the GSA is to continue to contribute to Scotland, the UK and beyond. Every Mackintosh Library by Lord year 300 students graduate from the GSA and Heather Walton talks to some Macfarlane of Bearsden, the School’s Honorary President. of them about the role the GSA plays in the cultural, social and economic life In his after dinner speech, Lord of the nation. One such graduate is the artist Ken Currie, recently appointed Wilson of Tillyorn, the recently appointed Chairman of the Visiting Professor within the School of Fine Art, interviewed here by Susannah National Museums of Scotland, Thompson. -

The Arts and Crafts Movement: Exchanges Between Greece and Britain (1876-1930)

The Arts and Crafts Movement: exchanges between Greece and Britain (1876-1930) M.Phil thesis Mary Greensted University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Contents Introduction 1 1. The Arts and Crafts Movement: from Britain to continental 11 Europe 2. Arts and Crafts travels to Greece 27 3 Byzantine architecture and two British Arts and Crafts 45 architects in Greece 4. Byzantine influence in the architectural and design work 69 of Barnsley and Schultz 5. Collections of Greek embroideries in England and their 102 impact on the British Arts and Crafts Movement 6. Craft workshops in Greece, 1880-1930 125 Conclusion 146 Bibliography 153 Acknowledgements 162 The Arts and Crafts Movement: exchanges between Greece and Britain (1876-1930) Introduction As a museum curator I have been involved in research around the Arts and Crafts Movement for exhibitions and publications since 1976. I have become both aware of and interested in the links between the Movement and Greece and have relished the opportunity to research these in more depth. It has not been possible to undertake a complete survey of Arts and Crafts activity in Greece in this thesis due to both limitations of time and word constraints. -

Works in the Kipling Collection "After" : Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1924 BOOK PR 4854 R4 1924 "After"

Works in the Kipling Collection Title Main Author Publication Year Material Type Call Number "After" : Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1924 BOOK PR 4854 R4 1924 "After" : Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1924 BOOK PR 4854 R4 1924 "Collectanea" Rudyard Kipling. Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1908 BOOK PR 4851 1908 "Curry & rice," on forty plates ; or, The ingredients of social life at Atkinson, George Francklin. 1859 BOOK DS 428 A76 1859 "our station" in India / : "Echoes" by two writers. Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1884 BOOK PR 4854 E42 1884 "Kipling and the doctors" : Bateson, Vaughan. 1929 BOOK PR 4856 B3 "Teem"--a treasure-hunter / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1935 BOOK PR 4854 T26 1935 "Teem"--a treasure-hunter / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1938 BOOK PR 4854 T26 1938 "The Times" and the publishers. Publishers' Association. 1906 BOOK Z 323 T59 1906 "They" / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1905 BOOK PR 4854 T35 1905 "They" / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1905 BOOK PR 4854 T35 1905 "They" / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1905 BOOK PR 4854 T35 1905a "They" / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1905 BOOK PR 4854 T35 1905a "They" / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1906 BOOK PR 4854 T35 1906 "They" / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1905 BOOK PR 4854 T35 1905 "They"; and, The brushwood boy / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1925 BOOK PR 4854 T352 1925 "They"; and, The brushwood boy / Kipling, Rudyard, 1865-1936. 1926 BOOK PR 4854 T352 1926 [Autograph letter from Stephen Wheeler, editor of the Civil & Wheeler, Stephen, 1854-1937. 1882 BOOK PR 4856 A42 1882 military gazette, reporting his deputy [Diary, 1882]. -

Joseph Beuys and the Reincarnation of German Romanticism

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-2003 Postwar Landscapes: Joseph Beuys and the Reincarnation of German Romanticism Lauren Elizabeth Smith University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Smith, Lauren Elizabeth, "Postwar Landscapes: Joseph Beuys and the Reincarnation of German Romanticism" (2003). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/601 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ----------------~~------~--------------------- Postwar Landscapes: Joseph Beuys and the Reincarnation of German Romanticism Lauren E. Smith College Scholars Senior Thesis University of Tennessee May 1,2003 Dr. Dorothy Habel, Dr. Tim Hiles, and Dr. Peter Hoyng, presiding committee Contents I. Introduction 3 II. Beuys' Germany: The 'Inability to Mourn' 3 III. Showman, Shaman, or Postwar Savoir? 5 IV. Beuys and Romanticism: Similia similibus curantur 9 V. Romanticism in Action: Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) 12 VI. Celtic+ ---: Germany's symbolic salvation in Basel 22 VII. Conclusion 27 Notes Bibliography Figures Germany, 1952 o Germany, you're torn asunder And not just from within! Abandoned in cold and darkness The one leaves the other alone. And you've got such lovely valleys And plenty of thriving towns; If only you'd trust yourself now, Then all would be just fine. -

Michael Jackson's Gesamtkunstwerk

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 11, No. 5 (November 2015) Michael Jackson’s Gesamtkunstwerk: Artistic Interrelation, Immersion, and Interactivity From the Studio to the Stadium Sylvia J. Martin Michael Jackson produced art in its most total sense. Throughout his forty-year career Jackson merged art forms, melded genres and styles, and promoted an ethos of unity in his work. Jackson’s mastery of combined song and dance is generally acknowledged as the hallmark of his performance. Scholars have not- ed Jackson’s place in the lengthy soul tradition of enmeshed movement and mu- sic (Mercer 39; Neal 2012) with musicologist Jacqueline Warwick describing Jackson as “embodied musicality” (Warwick 249). Jackson’s colleagues have also attested that even when off-stage and off-camera, singing and dancing were frequently inseparable for Jackson. James Ingram, co-songwriter of the Thriller album hit “PYT,” was astonished when he observed Jackson burst into dance moves while recording that song, since in Ingram’s studio experience singers typically conserve their breath for recording (Smiley). Similarly, Bruce Swedien, Jackson’s longtime studio recording engineer, told National Public Radio, “Re- cording [with Jackson] was never a static event. We used to record with the lights out in the studio, and I had him on my drum platform. Michael would dance on that as he did the vocals” (Swedien ix-x). Surveying his life-long body of work, Jackson’s creative capacities, in fact, encompassed acting, directing, producing, staging, and design as well as lyri- cism, music composition, dance, and choreography—and many of these across genres (Brackett 2012). -

Guide to International Decorative Art Styles Displayed at Kirkland Museum

1 Guide to International Decorative Art Styles Displayed at Kirkland Museum (by Hugh Grant, Founding Director and Curator, Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art) Kirkland Museum’s decorative art collection contains more than 15,000 objects which have been chosen to demonstrate the major design styles from the later 19th century into the 21st century. About 3,500 design works are on view at any one time and many have been loaned to other organizations. We are recognized as having one of the most important international modernist collections displayed in any North American museum. Many of the designers listed below—but not all—have works in the Kirkland Museum collection. Each design movement is certainly a confirmation of human ingenuity, imagination and a triumph of the positive aspects of the human spirit. Arts & Crafts, International 1860–c. 1918; American 1876–early 1920s Arts & Crafts can be seen as the first modernistic design style to break with Victorian and other fashionable styles of the time, beginning in the 1860s in England and specifically dating to the Red House of 1860 of William Morris (1834–1896). Arts & Crafts is a philosophy as much as a design style or movement, stemming from its application by William Morris and others who were influenced, to one degree or another, by the writings of John Ruskin and A. W. N. Pugin. In a reaction against the mass production of cheap, badly- designed, machine-made goods, and its demeaning treatment of workers, Morris and others championed hand- made craftsmanship with quality materials done in supportive communes—which were seen as a revival of the medieval guilds and a return to artisan workshops.