Catholics, Whiteness, and the Movies, 1928 - 1973

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

Itinéraires, 2019-2 Et 3 | 2019 Spencer Tracy Et La Reconfiguration De La Masculinité Hégémonique Américaine

Itinéraires Littérature, textes, cultures 2019-2 et 3 | 2019 Corps masculins et nation : textes, images, représentations Spencer Tracy et la reconfiguration de la masculinité hégémonique américaine après la Grande Dépression Spencer Tracy and the Reconfiguration of American Hegemonic Masculinity after the Great Depression Jules Sandeau Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/itineraires/6812 DOI : 10.4000/itineraires.6812 ISSN : 2427-920X Éditeur Pléiade Référence électronique Jules Sandeau, « Spencer Tracy et la reconfiguration de la masculinité hégémonique américaine après la Grande Dépression », Itinéraires [En ligne], 2019-2 et 3 | 2019, mis en ligne le 27 novembre 2019, consulté le 15 décembre 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/itineraires/6812 ; DOI : 10.4000/ itineraires.6812 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 15 décembre 2019. Itinéraires est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Spencer Tracy et la reconfiguration de la masculinité hégémonique américaine ... 1 Spencer Tracy et la reconfiguration de la masculinité hégémonique américaine après la Grande Dépression Spencer Tracy and the Reconfiguration of American Hegemonic Masculinity after the Great Depression Jules Sandeau 1 Si Spencer Tracy avait déjà acquis une certaine renommée pendant la première moitié des années 1930 (Loew 2008), notamment grâce à sa prestation dans The Power and the Glory (William K. Howard, 1933) qui reçut un très bon accueil critique (Curtis 2011 : 200, 208-210), ce sont ses rôles dans Fury (Fritz Lang, 1936) et San Francisco (W. S. Van Dyke, 1936) qui lui permirent de devenir une star hollywoodienne de premier plan au milieu de la décennie. -

HOLLYWOOD – the Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition

HOLLYWOOD – The Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition Paramount MGM 20th Century – Fox Warner Bros RKO Hollywood Oligopoly • Big 5 control first run theaters • Theater chains regional • Theaters required 100+ films/year • Big 5 share films to fill screens • Little 3 supply “B” films Hollywood Major • Producer Distributor Exhibitor • Distribution & Exhibition New York based • New York HQ determines budget, type & quantity of films Hollywood Studio • Hollywood production lots, backlots & ranches • Studio Boss • Head of Production • Story Dept Hollywood Star • Star System • Long Term Option Contract • Publicity Dept Paramount • Adolph Zukor • 1912- Famous Players • 1914- Hodkinson & Paramount • 1916– FP & Paramount merge • Producer Jesse Lasky • Director Cecil B. DeMille • Pickford, Fairbanks, Valentino • 1933- Receivership • 1936-1964 Pres.Barney Balaban • Studio Boss Y. Frank Freeman • 1966- Gulf & Western Paramount Theaters • Chicago, mid West • South • New England • Canada • Paramount Studios: Hollywood Paramount Directors Ernst Lubitsch 1892-1947 • 1926 So This Is Paris (WB) • 1929 The Love Parade • 1932 One Hour With You • 1932 Trouble in Paradise • 1933 Design for Living • 1939 Ninotchka (MGM) • 1940 The Shop Around the Corner (MGM Cecil B. DeMille 1881-1959 • 1914 THE SQUAW MAN • 1915 THE CHEAT • 1920 WHY CHANGE YOUR WIFE • 1923 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS • 1927 KING OF KINGS • 1934 CLEOPATRA • 1949 SAMSON & DELILAH • 1952 THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH • 1955 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS Paramount Directors Josef von Sternberg 1894-1969 • 1927 -

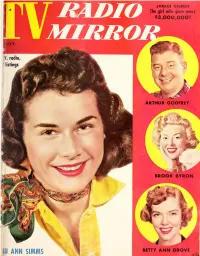

Radio TV Mirror

JANICE GILBERT The girl who gave away MIRRO $3,000,000! ARTHUR GODFREY BROOK BYRON BETTY LU ANN SIMMS ANN GROVE ! ^our new Lilt home permaTient will look , feel and stay like the loveliest naturally curly hair H.1 **r Does your wave look as soft and natural as the Lilt girl in our picture? No? Then think how much more beautiful you can be, when you change to Lilt with its superior ingredients. You'll be admired by men . envied by women ... a softer, more charming you. Because your Lilt will look, feel and stay like naturally curly hair. Watch admiring eyes light up, when you light up your life with a Lilt. $150 Choose the Lilt especially made for your type of hair! plus tax Procter £ Gambles new Wt guiJ. H Home Permanent tor hard-to-wave hair for normal hair for easy-to-wave hair for children's hair — . New, better way to reduce decay after eating sweets Always brush with ALL- NEW IPANA after eating ... as the Linders do . the way most dentists recommend. New Ipana with WD-9 destroys tooth-decay bacteria.' s -\V 77 If you eat sweet treats (like Stasia Linder of Massa- Follow Stasia Linder's lead and use new Ipana regularly pequa, N. Y., and her daughter Darryl), here's good news! after eatin g before decay bacteria can do their damage. You can do a far better job of preventing cavities by Even if you can't always brush after eating, no other brushing after eatin g . and using remarkable new Ipana tooth paste has ever been proved better for protecting Tooth Paste. -

Eastern Progress 1979-1980 Eastern Progress

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Eastern Progress 1979-1980 Eastern Progress 9-13-1979 Eastern Progress - 13 Sep 1979 Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1979-80 Recommended Citation Eastern Kentucky University, "Eastern Progress - 13 Sep 1979" (1979). Eastern Progress 1979-1980. Paper 4. http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1979-80/4 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Eastern Progress at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eastern Progress 1979-1980 by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. % » 14 l»4»es Vol.58/No. 4 Official Stud.nl Publication of Eaatarn Kentucky' Unnreraity Thund.y. Saptm.bar 13. 1979 Richmond. Ky- 40475 College of Business seeks accreditation Faculty Senate approves phasing out of seven associate degrees B\ ROBIN PATER separate faculty would be too costly. inflated." Thompson told the Progress ratio of student credit hours taught per New* Kditor Thompson explained later Some students who take evening faculty member, explained Thompson Approval of the proposed phasing out Consequently, in seeking ac- classes - only one or two classes - In other business discussed at the of seven associate degree programs in creditation from the American never intend to get a degree, he added Kaculty Senate meeting, a request for the College of Business highlighted the Assembly of Collegiate Schools of "The students about half of them approval of a new associate degree in meeting of the Kaculty Senate on Business 1AACSB1. these programs would go ahead and get their degrees " quality assurance technology was Monday must be dropped in order to comply The total number of graduates from passed The degree, which involves a The action cleared the way for the with Ihe rules of accreditation that the the College of Business for last year, cooperative arrangement with the last hurdle for the proposal, which is AACSB has set up including the summer session of 1979. -

Books Keeping for Auction

Books Keeping for Auction - Sorted by Artist Box # Item within Box Title Artist/Author Quantity Location Notes 1478 D The Nude Ideal and Reality Photography 1 3410-F wrapped 1012 P ? ? 1 3410-E Postcard sized item with photo on both sides 1282 K ? Asian - Pictures of Bruce Lee ? 1 3410-A unsealed 1198 H Iran a Winter Journey ? 3 3410-C3 2 sealed and 1 wrapped Sealed collection of photographs in a sealed - unable to 1197 B MORE ? 2 3410-C3 determine artist or content 1197 C Untitled (Cover has dirty snowman) ? 38 3410-C3 no title or artist present - unsealed 1220 B Orchard Volume One / Crime Victims Chronicle ??? 1 3410-L wrapped and signed 1510 E Paris ??? 1 3410-F Boxed and wrapped - Asian language 1210 E Sputnick ??? 2 3410-B3 One Russian and One Asian - both are wrapped 1213 M Sputnick ??? 1 3410-L wrapped 1213 P The Banquet ??? 2 3410-L wrapped - in Asian language 1194 E ??? - Asian ??? - Asian 1 3410-C4 boxed wrapped and signed 1180 H Landscapes #1 Autumn 1997 298 Scapes Inc 1 3410-D3 wrapped 1271 I 29,000 Brains A J Wright 1 3410-A format is folded paper with staples - signed - wrapped 1175 A Some Photos Aaron Ruell 14 3410-D1 wrapped with blue dot 1350 A Some Photos Aaron Ruell 5 3410-A wrapped and signed 1386 A Ten Years Too Late Aaron Ruell 13 3410-L Ziploc 2 soft cover - one sealed and one wrapped, rest are 1210 B A Village Destroyed - May 14 1999 Abrahams Peress Stover 8 3410-B3 hardcovered and sealed 1055 N A Village Destroyed May 14, 1999 Abrahams Peress Stover 1 3410-G Sealed 1149 C So Blue So Blue - Edges of the Mediterranean -

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960S

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s By Zachary Saltz University of Kansas, Copyright 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts ________________________________ Dr. Michael Baskett ________________________________ Dr. Chuck Berg Date Defended: 19 April 2011 ii The Thesis Committee for Zachary Saltz certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts Date approved: 19 April 2011 iii ABSTRACT The Green Sheet was a bulletin created by the Film Estimate Board of National Organizations, and featured the composite movie ratings of its ten member organizations, largely Protestant and represented by women. Between 1933 and 1969, the Green Sheet was offered as a service to civic, educational, and religious centers informing patrons which motion pictures contained potentially offensive and prurient content for younger viewers and families. When the Motion Picture Association of America began underwriting its costs of publication, the Green Sheet was used as a bartering device by the film industry to root out municipal censorship boards and legislative bills mandating state classification measures. The Green Sheet underscored tensions between film industry executives such as Eric Johnston and Jack Valenti, movie theater owners, politicians, and patrons demanding more integrity in monitoring changing film content in the rapidly progressive era of the 1960s. Using a system of symbolic advisory ratings, the Green Sheet set an early precedent for the age-based types of ratings the motion picture industry would adopt in its own rating system of 1968. -

![1946-05-31, [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1501/1946-05-31-p-631501.webp)

1946-05-31, [P ]

Friday, May 31, 194(1 THE TOLEDO UNION JOURNAL Page Fiv< Stanwyck, Cummings A Ri$t In New Film A Love-ly Moment In Paramount’s Delight Newsmiiil o£ Siage Screen ■' ---------------------:---------------------- by Burny Zawodny ....................................................... ■ llobert Cummings hilariously strives to catch Barbara Stan Star Saves Place For wyck with her boots off throughout the entire running time of Ex-Boom mate Olivia de Havilland Pqramount’s modern comedy-romance, "The Bride .Wore Boots,” By Wiley Pattani which opened at lhe Paramount Theatre \ with Diana HOLLYWOOD — Before [ITS TRUE! the war took them away Gagg 5X ith Director Lynn also starred. In othef words, * Bob objects to sharing from the Hollywood scene Barbara’! affections with the r. *?*’*_* ^ ! ''' ' $£ i/'' HOLLYWOOD — Olivia de . six years ago, David Niven Havilland, where a joke is con tAtnrrz Ata-Svdrses she3UC adores,auuxco, andaiiw which he and Robert Coote shared cerned, can give it out and take Filming > . bachelor's abode at Santa (Hkors with equal zest.. He fi W: it with the best of them. MfLWIOR, Monica, their domicile be On the first day’s shooting of ME^EOPOLITAb nally succeeds Story Gigantic ing known as "Cirhossis by in proving Paramount’s "To Each His OPERA STAA himself the the Sea.” Own,” the star’s dressing room >4AS BtEN Hollywood Job Niven, resuming his NIG^TED BY more desirable was crammed with flowers. One American screen career in IN6 Oifc^TiAN of the two, but of the particularly striking bou HOLLYWOOD ,(jS p e c j a 1)— "The Perfect Marriage,” DEMARK only after a se quets bore the name of Sidney X One of the biggest production Hal Wallis production for Lanfield. -

December 2018

LearnAboutMoviePosters.com December 2018 EWBANK’S AUCTIONS VINTAGE POSTER AUCTION DECEMBER 14 Ewbank's Auctions will present their Entertainment Memorabilia Auction on December 13 and Vintage Posters Auction on December 14. Star Wars and James Bond movie posters are just some of the highlights of this great auction featuring over 360 lots. See page 3. PART III ENDING TODAY - 12/13 PART IV ENDS 12/16 UPCOMING EVENTS/DEADLINES eMovieposter.com’s December Major Auction - Dec. 9-16 Part IV Dec. 13 Ewbank’s Entertainment & Memorabilia Auction Dec. 14 Ewbank’s Vintage Poster Auction Jan. 17, 2019 Aston’s Entertainment and Memorabilia Auction Feb. 28, 2019 Ewbank’s Entertainment & Memorabilia Auction Feb. 28, 2019 Ewbank’s Movie Props Auction March 1, 2019 Ewbank’s Vintage Poster Auction March 23, 2019 Heritage Auction LAMP’s LAMP POST Film Accessory Newsletter features industry news as well as product and services provided by Sponsors and Dealers of Learn About Movie Posters and the Movie Poster Data Base. To learn more about becoming a LAMP sponsor, click HERE! Add your name to our Newsletter Mailing List HERE! Visit the LAMP POST Archive to see early editions from 2001-PRESENT. The link can be found on the home page nav bar under “General” or click HERE. The LAMPPOST is a publication of LearnAboutMoviePosters.com Telephone: (504) 298-LAMP email: [email protected] Copyright 20178- Learn About Network L.L.C. 2 EWBANK’S AUCTIONS PRESENTS … ENTERTAINMENT & MEMORABILIA AUCTION - DECEMBER 13 & VINTAGE POSTER AUCTION - DECEMBER 14 Ewbank’s Auction will present their Entertainment & Memorabilia Auction on December 13 and their Vintage Poster Auction on December 14. -

Addison Richards Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

Addison Richards 电影 串行 (大全) Reprisal! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/reprisal%21-3930254/actors Let's Be Ritzy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/let%27s-be-ritzy-22079442/actors Inside Information https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/inside-information-18465537/actors Always a Bridesmaid https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/always-a-bridesmaid-23020746/actors Blue, White and Perfect https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/blue%2C-white-and-perfect-20649374/actors Little Big Shot https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/little-big-shot-6649096/actors Draegerman Courage https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/draegerman-courage-10576589/actors Where Are Your Children? https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/where-are-your-children%3F-3567712/actors A Close Call for Ellery https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-close-call-for-ellery-queen-84366182/actors Queen Gateway https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/gateway-11612443/actors The Girl from Missouri https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-girl-from-missouri-1753876/actors Accidents Will Happen https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/accidents-will-happen-16038863/actors Whispering Enemies https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/whispering-enemies-4019495/actors The Gambler Wore a Gun https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-gambler-wore-a-gun-15599546/actors A-Haunting We Will Go https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-haunting-we-will-go-3005526/actors Design for Scandal https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/design-for-scandal-5264339/actors -

THE DARK PAGES the Newsletter for Film Noir Lovers Vol

THE DARK PAGES The Newsletter for Film Noir Lovers Vol. 6, Number 1 SPECIAL SUPER-SIZED ISSUE!! January/February 2010 From Sheet to Celluloid: The Maltese Falcon by Karen Burroughs Hannsberry s I read The Maltese Falcon, by Dashiell Hammett, I decide on who will be the “fall guy” for the murders of Thursby Aactually found myself flipping more than once to check and Archer. As in the book, the film depicts Gutman giving Spade the copyright, certain that the book couldn’t have preceded the an envelope containing 10 one-thousand dollar bills as a payment 1941 film, so closely did the screenplay follow the words I was for the black bird, and Spade hands it over to Brigid for safe reading. But, to be sure, the Hammett novel was written in 1930, keeping. But when Brigid heads for the kitchen to make coffee and the 1941 film was the third of three features based on the and Gutman suggests that she leave the cash-filled envelope, he book. (The first, released in 1931, starred Ricardo Cortez and announces that it now only contains $900. Spade immediately Bebe Daniels, and the second, the 1936 film, Satan Met a Lady, deduces that Gutman palmed one of the bills and threatens to was a light comedy with Warren William and Bette Davis.) “frisk” him until the fat man admits that Spade is correct. But For my money, and for most noirists, the 94 version is the a far different scene played out in the book where, when the definitive adaptation. missing bill is announced, Spade ushers Brigid The 1941 film starred Humphrey Bogart into the bathroom and orders her to strip naked as private detective Sam Spade, along with to prove her innocence. -

Mary in Film

PONT~CALFACULTYOFTHEOLOGY "MARIANUM" INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE (UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON) MARY IN FILM AN ANALYSIS OF CINEMATIC PRESENTATIONS OF THE VIRGIN MARY FROM 1897- 1999: A THEOLOGICAL APPRAISAL OF A SOCIO-CULTURAL REALITY A thesis submitted to The International Marian Research Institute In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Licentiate of Sacred Theology (with Specialization in Mariology) By: Michael P. Durley Director: Rev. Johann G. Roten, S.M. IMRI Dayton, Ohio (USA) 45469-1390 2000 Table of Contents I) Purpose and Method 4-7 ll) Review of Literature on 'Mary in Film'- Stlltus Quaestionis 8-25 lli) Catholic Teaching on the Instruments of Social Communication Overview 26-28 Vigilanti Cura (1936) 29-32 Miranda Prorsus (1957) 33-35 Inter Miri.fica (1963) 36-40 Communio et Progressio (1971) 41-48 Aetatis Novae (1992) 49-52 Summary 53-54 IV) General Review of Trends in Film History and Mary's Place Therein Introduction 55-56 Actuality Films (1895-1915) 57 Early 'Life of Christ' films (1898-1929) 58-61 Melodramas (1910-1930) 62-64 Fantasy Epics and the Golden Age ofHollywood (1930-1950) 65-67 Realistic Movements (1946-1959) 68-70 Various 'New Waves' (1959-1990) 71-75 Religious and Marian Revival (1985-Present) 76-78 V) Thematic Survey of Mary in Films Classification Criteria 79-84 Lectures 85-92 Filmographies of Marian Lectures Catechetical 93-94 Apparitions 95 Miscellaneous 96 Documentaries 97-106 Filmographies of Marian Documentaries Marian Art 107-108 Apparitions 109-112 Miscellaneous 113-115 Dramas