Trapped in the Twilight Zone? Sweden Between Neutrality and Nato

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Hultqvist MINISTRY of DEFENCE

THE SWEDISH GOVERNMENT Following the 2014 change of government, Sweden is governed by the Swedish Social Democratic Party and the Green Party. CURRICULUM VITAE Minister for Defence Peter Hultqvist MINISTRY OF DEFENCE Party Swedish Social Democratic Party Areas of responsibility • Defence issues Personal Born 1958. Lives in Borlänge. Married. Educational background 1977 Hagaskolan, social science programme 1976 Soltorgsskolan, technical upper secondary school 1975 Gylle skola, compulsory school Posts and assignments 2014– Minister for Defence 2011–2014 Chair, Parliamentary Committee on Defence Member, Defence Commission 2010–2011 Group leader, Parliamentary Committee on the Constitution 2009–2014 Board member, Dalecarlia Fastighets AB (owned by HSB Dalarna) 2009–2014 Board member, Bergslagens Mark och Trädgård AB (owned by HSB Dalarna) 2009–2014 Chair, HSB Dalarna economic association 2009– Alternate member, Swedish Social Democratic Party Executive Committee 2006–2010 Member, Parliamentary Committee on Education 2006–2014 Member of the Riksdag 2005–2009 Member, National Board of the Swedish Social Democratic Party 2002–2006 Chair, Region Dalarna – the Regional Development Council of Dalarna County 2001–2005 Alternate member, National Board of the Swedish Social Democratic Party 2001– Chair, Swedish Social Democratic Party in Dalarna 1999–2006 Board member, Borlänge Energi AB 1999–2006 Chair, Koncernbolaget Borlänge Kommun (municipality group company) Please see next page 1998–2006 Municipal Commissioner in Borlänge, Chair of the Municipal -

1St First Society Handbook AFB Album of Favorite Barber Shop Ballads, Old and Modern

1st First Society Handbook AFB Album of Favorite Barber Shop Ballads, Old and Modern. arr. Ozzie Westley (1944) BPC The Barberpole Cat Program and Song Book. (1987) BB1 Barber Shop Ballads: a Book of Close Harmony. ed. Sigmund Spaeth (1925) BB2 Barber Shop Ballads and How to Sing Them. ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1940) CBB Barber Shop Ballads. (Cole's Universal Library; CUL no. 2) arr. Ozzie Westley (1943?) BC Barber Shop Classics ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1946) BH Barber Shop Harmony: a Collection of New and Old Favorites For Male Quartets. ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1942) BM1 Barber Shop Memories, No. 1, arr. Hugo Frey (1949) BM2 Barber Shop Memories, No. 2, arr. Hugo Frey (1951) BM3 Barber Shop Memories, No. 3, arr, Hugo Frey (1975) BP1 Barber Shop Parade of Quartet Hits, no. 1. (1946) BP2 Barber Shop Parade of Quartet Hits, no. 2. (1952) BP Barbershop Potpourri. (1985) BSQU Barber Shop Quartet Unforgettables, John L. Haag (1972) BSF Barber Shop Song Fest Folio. arr. Geoffrey O'Hara. (1948) BSS Barber Shop Songs and "Swipes." arr. Geoffrey O'Hara. (1946) BSS2 Barber Shop Souvenirs, for Male Quartets. New York: M. Witmark (1952) BOB The Best of Barbershop. (1986) BBB Bourne Barbershop Blockbusters (1970) BB Bourne Best Barbershop (1970) CH Close Harmony: 20 Permanent Song Favorites. arr. Ed Smalle (1936) CHR Close Harmony: 20 Permanent Song Favorites. arr. Ed Smalle. Revised (1941) CH1 Close Harmony: Male Quartets, Ballads and Funnies with Barber Shop Chords. arr. George Shackley (1925) CHB "Close Harmony" Ballads, for Male Quartets. (1952) CHS Close Harmony Songs (Sacred-Secular-Spirituals - arr. -

(2016) When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi

When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi Random House Publishing Group (2016) http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi Copyright © 2016 by Corcovado, Inc. Foreword copyright © 2016 by Abraham Verghese All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. RANDOM HOUSE and the HOUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kalanithi, Paul, author. Title: When breath becomes air / Paul Kalanithi ; foreword by Abraham Verghese. Description: New York : Random House, 2016. Identifiers: LCCN 2015023815 | ISBN 9780812988406 (hardback) | ISBN 9780812988413 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Kalanithi, Paul—Health. | Lungs—Cancer—Patients—United States—Biography. | Neurosurgeons—Biography. | Husband and wife. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs. | MEDICAL / General. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Death & Dying. Classification: LCC RC280.L8 K35 2016 | DDC 616.99/424—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015023815 eBook ISBN 9780812988413 randomhousebooks.com Book design by Liz Cosgrove, adapted for eBook Cover design: Rachel Ake v4.1 ep http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Editor's Note Epigraph Foreword by Abraham Verghese Prologue Part I: In Perfect Health I Begin Part II: Cease Not till Death Epilogue by Lucy Kalanithi Dedication Acknowledgments About the Author http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi EVENTS DESCRIBED ARE BASED on Dr. Kalanithi’s memory of real-world situations. However, the names of all patients discussed in this book—if given at all—have been changed. -

11-9-16 Full Paper

The Diocese of Ogdensburg Volume 71, Number 26 INSIDE THIS ISSUE The role of parents in the growth of NORTH COUNTRY vocations I PAGE 11 Advice for parents on screen time for kids I PAG E12 CATHOLIC NOV 9, 2016 All people long for mercy IN SUPPORT VAllCANCITY(CNS)-- Authentic re Buddhist, Sikh and other re The leaders were in Rome a day passes that we do not ligions help people under ligious leaders. for a conference on religions hear of acts of violence, con OF VOCATIONS stand that they are, in fact, "We seek a love that en and mercy organized by the flict, kidnapping, terrorist at loved and can be forgiven dures beyond momentary Pontifical Council for Interre tacks, killings and 'Come Holy and are called to love and pleasures, a safe harbor ligious Dialogue and the In destruction. Spirit, come' forgive others, Pope Francis where we can end our rest ternational Dialogue Center, "It is horrible that at times, said. less wanderings, an infinite which was founded in 2012 to justify such barbarism, "We thirst for mercy, and embrace that forgives and by Saudi Arabia, Austria and the name of a religion or the no technology can quench reconciles," the pope told the Spain with the support of the name of God himself is in that thirst," the pope told leaders Nov. 3 during an au Holy See. voked," Pope Francis told the Jewish, Christian, Muslim, dience at the Vatican. "Sadly," the pope said, "not group. Annual report AT THE BLUE MASS of diocesan Foundation PHOTO BY FR. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Party Leadership Selection in Parliamentary Democracies Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8fs1h45n Author So, Florence Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California University of California Los Angeles Party Leadership Selection in Parliamentary Democracies Adissertationsubmittedinpartialsatisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Florence Grace Hoi Yin So 2012 c Copyright by Florence Grace Hoi Yin So 2012 Abstract of the Dissertation Party Leadership Selection in Parliamentary Democracies by Florence Grace Hoi Yin So Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Kathleen Bawn, Chair My doctoral dissertation begins with this puzzle: why do large, moderate parties sometimes select leaders who seem to help improve their parties’ electoral performances, but other times choose unpopular leaders with more extreme policy positions, in expense of votes? I argue that leadership selection is dependent on both the electoral institution that a party finds itself in and the intra-party dynamics that constrain the party. Due to a high degree of seat- vote elasticity that is characteristic of majoritarian systems, replacing unpopular leaders is a feasible strategy for opposition parties in these systems to increase their seat shares. In contrast, in proportional systems, due to low seat-vote elasticity, on average opposition parties that replace their leaders su↵er from vote loss. My model of party leadership selection shows that since party members can provide valuable election campaign e↵ort, they can coerce those who select the party leader (the selectorate) into choosing their preferred leader. -

NATO Summit Guide Brussels, 11-12 July 2018

NATO Summit Guide Brussels, 11-12 July 2018 A stronger and more agile Alliance The Brussels Summit comes at a crucial moment for the security of the North Atlantic Alliance. It will be an important opportunity to chart NATO’s path for the years ahead. In a changing world, NATO is adapting to be a more agile, responsive and innovative Alliance, while defending all of its members against any threat. NATO remains committed to fulfilling its three core tasks: collective defence, crisis management and cooperative security. At the Brussels Summit, the Alliance will make important decisions to further boost security in and around Europe, including through strengthened deterrence and defence, projecting stability and fighting terrorism, enhancing its partnership with the European Union, modernising the Alliance and achieving fairer burden-sharing. This Summit will be held in the new NATO Headquarters, a modern and sustainable home for a forward-looking Alliance. It will be the third meeting of Allied Heads of State and Government chaired by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg. + Summit meetings + Member countries + Partners + NATO Secretary General Archived material – Information valid up to 10 July 2018 1 NATO Summit Guide, Brussels 2018 I. Strengthening deterrence and defence NATO’s primary purpose is to protect its almost one billion citizens and to preserve peace and freedom. NATO must also be vigilant against a wide range of new threats, be they in the form of computer code, disinformation or foreign fighters. The Alliance has taken important steps to strengthen its collective defence and deterrence, so that it can respond to threats from any direction. -

Och Försvarspolitiskt Samarbete Inklusive Krisberedskap

2012/13 mnr: U21 pnr: S29007 Motion till riksdagen 2012/13:U21 av Urban Ahlin m.fl. (S) med anledning av skr. 2012/13:112 Nordiskt utrikes-, säkerhets- och försvarspolitiskt samarbete inklusive krisberedskap Förslag till riksdagsbeslut 1. Riksdagen tillkännager för regeringen som sin mening vad som anförs i motionen om utrikes-, säkerhets- och försvarspolitiskt samarbete i Nor- den. 2. Riksdagen tillkännager för regeringen som sin mening vad som anförs i motionen om samarbete inom Förenta nationerna. 3. Riksdagen tillkännager för regeringen som sin mening vad som anförs i motionen om samarbete inom Europeiska unionen. 4. Riksdagen tillkännager för regeringen som sin mening vad som anförs i motionen om samarbete med Nato. 5. Riksdagen tillkännager för regeringen som sin mening vad som anförs i motionen om ett utvecklat nordiskt försvarssamarbete. Utrikes-, säkerhets- och försvarspolitiskt samarbete i Norden Samarbetet mellan de nordiska länderna är starkt och vilar på en gedigen folklig förankring. Det nordiska samarbetet berör många olika områden och har bidragit till att göra Norden till en region i världsklass. Vi anser att detta samarbete ska stärkas och utvecklas. Vi socialdemokrater anser att Sverige ska vara militärt alliansfritt. Vi säger nej till medlemskap i Nato. En modern svensk säkerhetspolitik byggs på ett ökat nordiskt samarbete, en aktiv Östersjöpolitik, ett fördjupat samarbete i EU och ett starkare stöd till Förenta nationerna. Sverige ska inte förhålla sig pas- sivt om en katastrof eller ett angrepp skulle drabba ett EU-land eller ett nor- 1 Fel! Okänt namn på dokumentegenskap. :Fel! diskt land och vi förväntar oss att dessa länder agerar på samma sätt om Sve- Okänt namn på rige drabbas. -

Föredragningslista

Föredragningslista 2008/09:70 Fredagen den 13 februari 2009 Kl. 09.00 Interpellationssvar ____________________________________________________________ Avsägelse 1 Laila Bjurling (s) som suppleant i Nordiska rådets svenska delegation 2 Anmälan om sammansatt utrikes- och försvarsutskott Anmälan om fördröjda svar på interpellationer 3 2008/09:272 av Peter Hultqvist (s) Begreppet utanförskap 4 2008/09:306 av Helene Petersson i Stockaryd (s) Småhusindustrin och bostadsbyggandet 5 2008/09:310 av Olof Lavesson (m) Öresundsintegrationen under det svenska EU-ordförandeskapet 6 2008/09:322 av Veronica Palm (s) Sjukskrivningsreglerna Svar på interpellationer Interpellationer upptagna under samma punkt besvaras i ett sammanhang Näringsminister Maud Olofsson (c) 7 2008/09:265 av Carina Adolfsson Elgestam (s) Glasriket Utrikesminister Carl Bildt (m) 8 2008/09:252 av Monica Green (s) Barnen på Gazaremsan 2008/09:267 av Peter Hultqvist (s) Produkter tillverkade på av Israel ockuperat område 1 (3) Fredagen den 13 februari 2009 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 2008/09:268 av Peter Hultqvist (s) Situationen i Gaza 2008/09:303 av Thomas Strand (s) Dialog med Hamas Statsrådet Mats Odell (kd) 9 2008/09:224 av Carina Adolfsson Elgestam (s) Tvångsförvaltning av hyresfastighet och hyresgästs rättigheter 10 2008/09:263 av Hans Hoff (s) Försäkringspremien för dem med betalningsanmärkning 11 2008/09:278 av Thomas Östros (s) Stabilitetsprogram för bankerna 12 2008/09:305 -

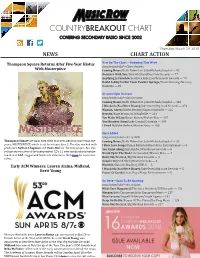

Countrybreakout Chart Covering Secondary Radio Since 2002

COUNTRYBREAKOUT CHART COVERING SECONDARY RADIO SINCE 2002 Thursday, March 29, 2018 NEWS CHART ACTION Thompson Square Returns After Five-Year Hiatus New On The Chart —Debuting This Week song/artist/label—Chart Position With Masterpiece Coming Home/Keith Urban feat. Julia Michaels/Capitol — 45 Nowhere With You/Dave McElroy/Free Flow Records — 77 Anything Is Possible/Southern Halo/Southern Halo Records — 79 David Ashley Parker From Powder Springs/Travis Denning/Mercury Nashville — 80 Greatest Spin Increase song/artist/label—Spin Increase Coming Home/Keith Urban feat. Julia Michaels/Capitol — 468 I Was Jack (You Were Diane)/Jake Owen/Big Loud Records — 372 Woman, Amen/Dierks Bentley/Capitol Nashville — 215 Heaven/Kane Brown/RCA Nashville — 214 You Make It Easy/Jason Aldean/Broken Bow — 207 One Number Away/Luke Combs/Columbia — 199 I Lived It/Blake Shelton/Warner Bros. — 183 Most Added song/artist/label—No. of Adds Thompson Square are back with their irst new album in more than ive Coming Home/Keith Urban feat. Julia Michaels/Capitol — 35 years, MASTERPIECE, which is set for release June 1. The duo worked with I Hate Love Songs/Kelsea Ballerini/Black River Entertainment — 9 producers Nathan Chapman and Dann Huff on the new project, but also You Came Along/Risa Binder/Warehouse Records — 8 self-produced a few of the independent CD’s 11 new tracks which feature Break Up In The End/Cole Swindell/Warner Bros. — 7 touches of R&B, reggae and hard rock in8luences. Click here for a preview Burn Out/Midland/Big Machine Records — 6 video. Keepin' On/Rod Black/Bristol Records — 6 Early ACM Winners: Lauren Alaina, Midland, Worth It/Danielle Bradbery/BMLG — 5 I Was Jack (You Were Diane)/Jake Owen/Big Loud Records — 5 Brett Young Power Of Garth/Lucas Hoge/Forge Entertainment — 5 On Deck—Soon To Be Charting song/artist/label—No. -

Verksamhetsberättelse 2020

Bilaga 2 Verksamhetsberättelse 2020 Socialdemokraterna i Kalmar län Distriktsstyrelsen Ordinarie ledamöter Anders Henriksson, Kalmar, ordförande Peter Wretlund, Oskarshamn, kassör Helen Nilsson, Vimmerby, vice ordförande Emöke Bokor, Söderåkra (till 27 oktober) Robert Rapakko, Mönsterås, studieledare Jonas Erlandsson, Högsby, facklig ledare Martina Aronsson, Alsterbro Gunnar Jansson, Västervik Lena Hallengren, Kalmar Maria Ixcot Nilsson, Emmaboda Mattias Nilsson, Mörbylånga (fram till 17 oktober) Marie-Helen Ståhl, Borgholm (fram till 17 oktober) Ilko Corkovic, Borgholm (från 17 oktober) Matilda Wärenfalk, Färjestaden (från 17 oktober) Nermina Mizimovic, Hultsfred Ersättare Michael Ländin, Kalmar Angelica Katsanidou, Överum Tobias Fagergård, Nybro Laila Naraghi, Oskarshamn Peter Högberg, Vimmerby Verkställande utskottet Anders Henriksson, Kalmar Helen Nilsson, Vimmerby Peter Wretlund, Oskarshamn Lena Hallengren, Kalmar Gunnar Jansson, Västervik Revisorer Herman Halvarsson, Köpingsvik Doris Johansson, Kalmar Monica Anderberg, Torsås Ersättare Ove Kåreberg, Mönsterås Diana Bergeskans, Högsby Mathias Karlsson, Färjestaden 2 Antal sammanträden Verkställande utskottet har haft 17st protokollförda sammanträden. Distriktsstyrelsen har haft 9st protokollförda sammanträden samt 1 per capsulam. Representation i partistyrelsen Ordinarie ledamot, Lena Hallengren, Kalmar och ersättare, Johan Persson, Kalmar. Valberedning 2019-2023 Ordinarie ledamöter Ewa Klase, Mönsterås Simon Pettersson, Emmaboda Ann-Britt Mårtensson, Torsås Yvonne Hagberg, Högsby, -

Carolina Hurricanes

CAROLINA HURRICANES NEWS CLIPPINGS • August 26, 2021 Durham Bulls honoring Hurricanes with Hockey Night at the DBAP Durham, N.C. — The Durham Bulls will hit the field for an Hurricanes players are expected to attend the game along upcoming home game looking like another one of the with Hurricanes mascot, Stormy! The Hurricanes' warning Triangle's favorite teams. siren will also be at the ballpark. Hockey Night is scheduled for Friday, Sept. 10. at Durham The Bulls are scheduled to take on the Norfolk Tides with a Bulls Athletic Park as the Bulls partner up with their friends at 6:35 p.m. first pitch. The Hurricanes will open the season the Carolina Hurricanes. against the New York Islanders on Thursday, Oct. 14 at PNC Arena. Bulls players and coaches will wear special Carolina Hurricanes-themed jerseys, which will be auctioned off to benefit the Carolina Hurricanes Foundation. Metropolitan Division review: Capitals, Penguins try for another run; Teams on the rise By Adam Gretz Bernier, Tomas Tatar, and Dougie Hamilton. Hamilton is the big addition here and arguably one of the biggest moves of Current Metropolitan Division Favorite: Hurricanes the offseason made by any NHL team. He is one of the top The New York Islanders have been in the Conference overall defensemen in the league. He drives possession at Finals/Semifinals two years in a row, the Pittsburgh Penguins an elite level, produces offense at an elite level, and is a and Washington Capitals still have their cores, and the New better, more impactful defender than he gets credit for being. -

Bet. 2007/08:NU4 Statliga Företag

Näringsutskottets betänkande 2007/08:NU4 Statliga företag Sammanfattning I anslutning till behandlingen av 2007 års redogörelse för statliga företag, vilken har överlämnats till riksdagen med regeringens skrivelse 2006/07: 120, avstyrker utskottet motionsyrkanden rörande synen på statligt ägande av företag och försäljningar av statliga bolag. Utskottet redovisar sin syn i dessa frågor. Den aktuella skrivelsen bör läggas till handlingarna. I en reser- vation (s, v) föreslås bl.a. att riksdagen ska återta det bemyndigande om försäljning som lämnades i juni 2007. I betänkandet behandlas vidare motionsyrkanden om statens ägarutöv- ning – allmänt och beträffande ersättning till ledande befattningshavare. Yrkandena avstyrks, huvudsakligen med hänvisning till pågående bered- ning inom regeringen. I olika reservationer från företrädarna för Socialde- mokraterna, Vänsterpartiet och Miljöpartiet följs yrkandena upp. 1 2007/08:NU4 Innehållsförteckning Sammanfattning .............................................................................................. 1 Utskottets förslag till riksdagsbeslut ............................................................... 4 Redogörelse för ärendet .................................................................................. 5 Utskottets överväganden ................................................................................. 6 Skrivelsen om statliga företag ...................................................................... 6 Motionerna ..................................................................................................