Sam Shepard's Angel City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sam Shepard One Acts: War in Heaven (Angel’S Monologue), the Curse of the Raven’S Black Feather, Hail from Nowhere, Just Space Rhythm

Sam Shepard One Acts: War in Heaven (Angel’s Monologue), The Curse of the Raven’s Black Feather, Hail from Nowhere, Just Space Rhythm Resource Guide for Teachers Created by: Lauren Bloom Hanover, Director of Education 1 Table of Contents About Profile Theatre 3 How to Use This Resource Guide 4 The Artists 5 Lesson 1: Who is Sam Shepard? Classroom Activities: 1) Biography and Context 6 2) Shepard in His Own Words 6 3) Shepard Adjectives 7 Lesson 2: Influences on Shepard Classroom Activities 1) Exploring Similar Themes in O’Neill and Shepard 16 2) Exploring Similar Styles in Beckett and Shepard 17 3) Exploring the Influence of Music on Shepard 18 Lesson 3: Inspired by Shepard Classroom Activities 1) Reading Samples of Shepard 28 2) Creative Writing Inspired by Shepard 29 3) Directing One’s Own Work 29 Lesson 4: What Are You Seeing Classroom Activities 1) Pieces Being Performed 33 2) Statues 34 3) Staging a Monologue 36 Lesson 5: Reflection Classroom Activities 1) Written Reflection 44 2) Putting It All Together 45 2 About Profile Theatre Profile Theatre was founded in 1997 with the mission of celebrating the playwright’s contribution to live theater. To that end, Profile programs a full season of the work of a single playwright. This provides our community with the opportunity to deeply engage with the work of our featured playwright through performances, readings, lectures and talkbacks, a unique experience in Portland. Our Mission realized... Profile invites our audiences to enter a writer’s world for a full season of plays and events. -

“The Wounded Angel Considers the Uses of So-Called Secular Literature to Convey Illuminations of Mystery, the Unsayable, the Hidden Otherness, the Holy One

“The Wounded Angel considers the uses of so-called secular literature to convey illuminations of mystery, the unsayable, the hidden otherness, the Holy One. Saint Ignatius urged us to find God in all things, and Paul Lakeland demonstrates how that’s theologically possible in fictions whose authors had no spiritual or religious intentions. A fine and much-needed reflection.” — Ron Hansen Santa Clara University “Renowned ecclesiologist Paul Lakeland explores in depth one of his earliest but perduring interests: the impact of reading serious modern fiction. He convincingly argues for an inner link between faith and religious imagination. Drawing on a copious cross section of thoughtful novels (not all of them ‘edifying’), he reasons that the joy of reading is more than entertainment but rather potentially salvific transformation of our capacity to love and be loved. Art may accomplish what religion does not always achieve. The numerous titles discussed here belong on one’s must-read list!” — Michael A. Fahey, SJ Fairfield University “Paul Lakeland claims that ‘the work of the creative artist is always somehow bumping against the transcendent.’ What a lovely thought and what a perfect summary of the subtle and significant argument made in The Wounded Angel. Gracefully moving between theology and literature, religious content and narrative form, Lakeland reminds us both of how imaginative faith is and of how imbued with mystery and grace literature is. Lakeland’s range of interests—Coleridge and Louise Penny, Marilynne Robinson and Shusaku Endo—is wide, and his ability to trace connections between these texts and relate them to large-scale theological questions is impressive. -

Angel Sanctuary, a Continuation…

Angel Sanctuary, A Continuation… Written by Minako Takahashi Angel Sanctuary, a series about the end of the world by Yuki Kaori, has entered the Setsuna final chapter. It is appropriately titled "Heaven" in the recent issue of Hana to Yume. However, what makes Angel Sanctuary unique from other end-of-the-world genre stories is that it does not have a clear-cut distinction between good and evil. It also displays a variety of worldviews with a distinct and unique cast of characters that, for fans of Yuki Kaori, are quintessential Yuki Kaori characters. With the beginning of the new chapter, many questions and motives from the earlier chapters are answered, but many more new ones arise as readers take the plunge and speculate on the series and its end. In the "Hades" chapter, Setsuna goes to the Underworld to bring back Sara's soul, much like the way Orpheus went into Hades to seek the soul of his love, Eurydice. Although things seem to end much like that ancient tale at the end of the chapter, the readers are not left without hope for a resolution. While back in Heaven, Rociel returns and thereby begins the political struggle between himself and the regime of Sevothtarte and Metatron that replaced Rociel while he was sealed beneath the earth. However the focus of the story shifts from the main characters to two side characters, Katou and Tiara. Katou was a dropout at Setsuna's school who was killed by Setsuna when he was possessed by Rociel. He is sent to kill Setsuna in order for him to go to Heaven. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

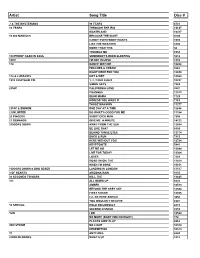

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

Download Book ~ Angel Sanctuary: V. 11 > XUY89Z31BVL3

NYX64JMHH8QK ~ PDF ~ Angel Sanctuary: v. 11 Angel Sanctuary: v. 11 Filesize: 1.63 MB Reviews Without doubt, this is the very best function by any writer. It typically will not charge too much. I discovered this publication from my dad and i encouraged this pdf to discover. (Clement Stanton) DISCLAIMER | DMCA 8G6XUG4NDSPA # PDF < Angel Sanctuary: v. 11 ANGEL SANCTUARY: V. 11 To download Angel Sanctuary: v. 11 eBook, please click the link under and download the document or gain access to additional information which are have conjunction with ANGEL SANCTUARY: V. 11 ebook. Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc. Paperback. Book Condition: new. BRAND NEW, Angel Sanctuary: v. 11, Kaori Yuki, Deep in Hell, Setsuna has finally found Kurai. But Hell and everyone in it will be destroyed if Kurai doesn't agree to go through with the marriage to Lucifer - who sacrifices his wives to stabilize his power! And in Heaven, the angel Raphael is trying to revive Setsuna's human body, with poor results. A mysterious power is preventing the resurrection spell from working, but Sara is not willing to give up. But when she uses the angel Jibril's powers to assist Raphael's efforts, they are both flung into another dimension!. Read Angel Sanctuary: v. 11 Online Download PDF Angel Sanctuary: v. 11 1EY2DKIPU2CC // Book \ Angel Sanctuary: v. 11 See Also [PDF] You Shouldn't Have to Say Goodbye: It's Hard Losing the Person You Love the Most Follow the web link beneath to download "You Shouldn't Have to Say Goodbye: It's Hard Losing the Person You Love the Most" PDF file. -

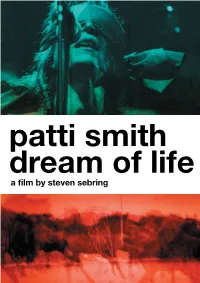

Patti DP.Indd

patti smith dream of life a film by steven sebring THIRTEEN/WNET NEW YORK AND CLEAN SOCKS PRESENT PATTI SMITH AND THE BAND: LENNY KAYE OLIVER RAY TONY SHANAHAN JAY DEE DAUGHERTY AND JACKSON SMITH JESSE SMITH DIRECTORS OF TOM VERLAINE SAM SHEPARD PHILIP GLASS BENJAMIN SMOKE FLEA DIRECTOR STEVEN SEBRING PRODUCERS STEVEN SEBRING MARGARET SMILOW SCOTT VOGEL PHOTOGRAPHY PHILLIP HUNT EXECUTIVE CREATIVE STEVEN SEBRING EDITORS ANGELO CORRAO, A.C.E, LIN POLITO PRODUCERS STEVEN SEBRING MARGARET SMILOW CONSULTANT SHOSHANA SEBRING LINE PRODUCER SONOKO AOYAGI LEOPOLD SUPERVISING INTERNATIONAL PRODUCERS JUNKO TSUNASHIMA KRISTIN LOVEJOY DISTRIBUTION BY CELLULOID DREAMS Thirteen / WNET New York and Clean Socks present Independent Film Competition: Documentary patti smith dream of life a film by steven sebring USA - 2008 - Color/B&W - 109 min - 1:66 - Dolby SRD - English www.dreamoflifethemovie.com WORLD SALES INTERNATIONAL PRESS CELLULOID DREAMS INTERNATIONAL HOUSE OF PUBLICITY 2 rue Turgot Sundance office located at the Festival Headquarters 75009 Paris, France Marriott Sidewinder Dr. T : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0370 F : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0371 Jeff Hill – cell: 917-575-8808 [email protected] E: [email protected] www.celluloid-dreams.com Michelle Moretta – cell: 917-749-5578 E: [email protected] synopsis Dream of Life is a plunge into the philosophy and artistry of cult rocker Patti Smith. This portrait of the legendary singer, artist and poet explores themes of spirituality, history and self expression. Known as the godmother of punk, she emerged in the 1970’s, galvanizing the music scene with her unique style of poetic rage, music and trademark swagger. -

Slayage, Number 16

Roz Kaveney A Sense of the Ending: Schrödinger's Angel This essay will be included in Stacey Abbott's Reading Angel: The TV Spinoff with a Soul, to be published by I. B. Tauris and appears here with the permission of the author, the editor, and the publisher. Go here to order the book from Amazon. (1) Joss Whedon has often stated that each year of Buffy the Vampire Slayer was planned to end in such a way that, were the show not renewed, the finale would act as an apt summation of the series so far. This was obviously truer of some years than others – generally speaking, the odd-numbered years were far more clearly possible endings than the even ones, offering definitive closure of a phase in Buffy’s career rather than a slingshot into another phase. Both Season Five and Season Seven were particularly planned as artistically satisfying conclusions, albeit with very different messages – Season Five arguing that Buffy’s situation can only be relieved by her heroic death, Season Seven allowing her to share, and thus entirely alleviate, slayerhood. Being the Chosen One is a fatal burden; being one of the Chosen Several Thousand is something a young woman might live with. (2) It has never been the case that endings in Angel were so clear-cut and each year culminated in a slingshot ending, an attention-grabber that kept viewers interested by allowing them to speculate on where things were going. Season One ended with the revelation that Angel might, at some stage, expect redemption and rehumanization – the Shanshu of the souled vampire – as the reward for his labours, and with the resurrection of his vampiric sire and lover, Darla, by the law firm of Wolfram & Hart and its demonic masters (‘To Shanshu in LA’, 1022). -

Sam Shepard's Dramaturgical Strategies Susan

Fall 1988 71 Estrangement and Engagement: Sam Shepard's Dramaturgical Strategies Susan Harris Smith Current scholarship reveals an understandable preoccupation with and confusion over Sam Shepard's most prominent characteristics, his language and imagery, both of which are seminal features of his technical innovation. In their attempts to describe or define Shepard's idiosyncratic dramaturgy, critics variously have called it absurdist, surrealistic, mythic, Brechtian, and even Artaudian. Most critics, too, are concerned primarily with his themes: physical violence, erotic dynamism, and psychological dissolution set against the cultural wasteland of modern America (Marranca, ed.). But in focusing on Shepard's imagery, language, and themes, some critics ignore theatrical performance. Beyond observing that many of Shepard's role-playing characters engage in power struggles with each other, few critics have concerned themselves with Shepard's structural strategies or with the ways in which he manipulates his audience. One who has addressed the issue, Bonnie Marranca, writes: Characters often engage in, "performance": they create roles for themselves and dialogue, structuring new realities. ... It might be called an aesthetics of actualism. In other words, the characters act themselves out, even make them• selves up, through the transforming power of their imagina• tion. An Assistant Professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh and the author of Masks in Modern Drama, Susan Harris Smith is currently working on a book on American drama. A shorter version of this article was presented at the South• eastern Modern Languages Association in 1985. 72 Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism Because the characters are so free of fixed reality, their imagination plays a key role in the narratives. -

True West Study Guide in Context 2

True West Study Guide by Course Hero who long to change their lives. This West is a rugged, romantic, What's Inside but often violent place where people are free to reinvent themselves. The play questions whether this idealized version of the West is real or true and ultimately suggests that the idea j Book Basics ................................................................................................. 1 of a true west is a fantasy. d In Context ..................................................................................................... 1 a Author Biography ..................................................................................... 3 d In Context h Characters .................................................................................................. 4 k Plot Summary ............................................................................................. 7 Shepard's "Double Nature" c Scene Summaries .................................................................................. 12 Austin and Lee, the brothers and main characters in True West, g Quotes ........................................................................................................ 25 are often considered one another's "doubles," or two sides of l Symbols ...................................................................................................... 27 the same person. "I wanted to write a play about double nature," Shepard said about the writing of True West. He m Themes ..................................................................................................... -

Buried Child by Sam Shepard

MEDIA CONTACT: Bernie Fabig, Marketing & Publicity Manager 310-756-2428 • [email protected] The third production of A Noise Within’s 2019-2020 Season: THEY PLAYED WITH FIRE Buried Child By Sam Shepard Directed by Julia Rodriguez-Elliott Oct. 19 – Nov. 23, 2019 Pasadena, Calif. (Oct. 19, 2019) – A Noise Within (ANW), California’s acclaimed classic repertory theatre company, is proud to present Sam Shepard’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Buried Child, directed by ANW Producing Artistic Director Julia Rodriguez-Elliott. Shepard’s remarkable masterpiece Buried Child will run Oct. 13 through Nov. 23, 2019 with press performances on Saturday, Oct. 19 at 8 p.m. and Sunday, Oct. 20 at 2 p.m. Set in America’s heartland, Sam Shepard’s powerful Pulitzer Prize-winning play details, with wry humor, the disintegration of the American Dream. When 22-year-old Vince unexpectedly shows up at the family farm with his girlfriend Shelly, no one recognizes him. So begins the unraveling of dark secrets. A surprisingly funny look at disillusionment and morality, Shepard’s masterpiece is the family reunion no one anticipated. “Buried Child is wickedly funny,” said Producing Artistic Director Julia Rodriguez-Elliott. “Sam Shepard has an uncanny way of bringing out the humor in dysfunction. There’s something familiar, yet not familiar about this family. It’s at once disconcertingly recognizable and inexplicably strange.” - more - MEDIA CONTACT: Bernie Fabig, Marketing & Publicity Manager 310-756-2428 • [email protected] In Buried Child, comedy meets the absurd in a bizarre twist on the family drama that scorches with a powerful commentary on the “American Dream” and what happens when a community simmers in neglect, resentment, and disowned memory. -

A Critical Study of the Family Crises in Sam Shepard’S Buried Child and True West

ABSTRACT RITUALS AND MYTHS: A CRITICAL STUDY OF THE FAMILY CRISES IN SAM SHEPARD’S BURIED CHILD AND TRUE WEST In this thesis, I examine two plays by Sam Shepard, Buried Child and True West, and how the family crises in each culminate in an act of ritual. Applying the framework of Rene Girard, I explore how these two plays express Girard’s theory of the role of ritual sacrifice in communities—specifically, that rituals can be traced back to an ancient act of sacrifice in which a community killed a scapegoated victim to maintain social cohesion and de-escalate the growing antagonism that threatened their society. Writing in the late 70s, Shepard’s work can be seen as a commentary on the Vietnam War. His work at this time reflects an American society that was increasingly aware of the sacrifices deemed necessary to maintain American exceptionalism. Shepard’s plays depict moments of ritual, but also confront the audience with their inherent violence and injustice. He works to deconstruct social myths that conceal this truth, particularly the “social myth” of traditional family roles. Ultimately, Shepard exposes the violence weaved into the social fabric of America, but also confronts the chaos that could erupt if that social fabric were to unravel. Nicholas Wogan May 2019 RITUALS AND MYTHS: A CRITICAL STUDY OF THE FAMILY CRISES IN SAM SHEPARD’S BURIED CHILD AND TRUE WEST by Nicholas Wogan A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English in the College of Arts and Humanities California State University, Fresno May 2019 APPROVED For the Department of English: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree.