Mathematically Talented Women in Hollywood: Fred in Angel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TASI Lectures on String Compactification, Model Building

CERN-PH-TH/2005-205 IFT-UAM/CSIC-05-044 TASI lectures on String Compactification, Model Building, and Fluxes Angel M. Uranga TH Unit, CERN, CH-1211 Geneve 23, Switzerland Instituto de F´ısica Te´orica, C-XVI Universidad Aut´onoma de Madrid Cantoblanco, 28049 Madrid, Spain angel.uranga@cern,ch We review the construction of chiral four-dimensional compactifications of string the- ory with different systems of D-branes, including type IIA intersecting D6-branes and type IIB magnetised D-branes. Such models lead to four-dimensional theories with non-abelian gauge interactions and charged chiral fermions. We discuss the application of these techniques to building of models with spectrum as close as possible to the Stan- dard Model, and review their main phenomenological properties. We finally describe how to implement the tecniques to construct these models in flux compactifications, leading to models with realistic gauge sectors, moduli stabilization and supersymmetry breaking soft terms. Lecture 1. Model building in IIA: Intersecting brane worlds 1 Introduction String theory has the remarkable property that it provides a description of gauge and gravitational interactions in a unified framework consistently at the quantum level. It is this general feature (beyond other beautiful properties of particular string models) that makes this theory interesting as a possible candidate to unify our description of the different particles and interactions in Nature. Now if string theory is indeed realized in Nature, it should be able to lead not just to `gauge interactions' in general, but rather to gauge sectors as rich and intricate as the gauge theory we know as the Standard Model of Particle Physics. -

“The Wounded Angel Considers the Uses of So-Called Secular Literature to Convey Illuminations of Mystery, the Unsayable, the Hidden Otherness, the Holy One

“The Wounded Angel considers the uses of so-called secular literature to convey illuminations of mystery, the unsayable, the hidden otherness, the Holy One. Saint Ignatius urged us to find God in all things, and Paul Lakeland demonstrates how that’s theologically possible in fictions whose authors had no spiritual or religious intentions. A fine and much-needed reflection.” — Ron Hansen Santa Clara University “Renowned ecclesiologist Paul Lakeland explores in depth one of his earliest but perduring interests: the impact of reading serious modern fiction. He convincingly argues for an inner link between faith and religious imagination. Drawing on a copious cross section of thoughtful novels (not all of them ‘edifying’), he reasons that the joy of reading is more than entertainment but rather potentially salvific transformation of our capacity to love and be loved. Art may accomplish what religion does not always achieve. The numerous titles discussed here belong on one’s must-read list!” — Michael A. Fahey, SJ Fairfield University “Paul Lakeland claims that ‘the work of the creative artist is always somehow bumping against the transcendent.’ What a lovely thought and what a perfect summary of the subtle and significant argument made in The Wounded Angel. Gracefully moving between theology and literature, religious content and narrative form, Lakeland reminds us both of how imaginative faith is and of how imbued with mystery and grace literature is. Lakeland’s range of interests—Coleridge and Louise Penny, Marilynne Robinson and Shusaku Endo—is wide, and his ability to trace connections between these texts and relate them to large-scale theological questions is impressive. -

Angel Sanctuary, a Continuation…

Angel Sanctuary, A Continuation… Written by Minako Takahashi Angel Sanctuary, a series about the end of the world by Yuki Kaori, has entered the Setsuna final chapter. It is appropriately titled "Heaven" in the recent issue of Hana to Yume. However, what makes Angel Sanctuary unique from other end-of-the-world genre stories is that it does not have a clear-cut distinction between good and evil. It also displays a variety of worldviews with a distinct and unique cast of characters that, for fans of Yuki Kaori, are quintessential Yuki Kaori characters. With the beginning of the new chapter, many questions and motives from the earlier chapters are answered, but many more new ones arise as readers take the plunge and speculate on the series and its end. In the "Hades" chapter, Setsuna goes to the Underworld to bring back Sara's soul, much like the way Orpheus went into Hades to seek the soul of his love, Eurydice. Although things seem to end much like that ancient tale at the end of the chapter, the readers are not left without hope for a resolution. While back in Heaven, Rociel returns and thereby begins the political struggle between himself and the regime of Sevothtarte and Metatron that replaced Rociel while he was sealed beneath the earth. However the focus of the story shifts from the main characters to two side characters, Katou and Tiara. Katou was a dropout at Setsuna's school who was killed by Setsuna when he was possessed by Rociel. He is sent to kill Setsuna in order for him to go to Heaven. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

Angel: Through My Eyes - Natural Disaster Zones by Zoe Daniel Series Editor: Lyn White

BOOK PUBLISHERS Teachers’ Notes Angel: Through My Eyes - Natural Disaster Zones by Zoe Daniel Series editor: Lyn White ISBN 9781760113773 Recommended for ages 11-14 yrs These notes may be reproduced free of charge for use and study within schools but they may not be reproduced (either in whole or in part) and offered for commercial sale. Introduction ............................................ 2 Links to the curriculum ............................. 5 Background information for teachers ....... 12 Before reading activities ......................... 14 During reading activities ......................... 16 After-reading activities ........................... 20 Enrichment activities ............................. 28 Further reading ..................................... 30 Resources ............................................ 32 About the writer and series editor ............ 32 Blackline masters .................................. 33 Allen & Unwin would like to thank Heather Zubek and Sunniva Midtskogen for their assistance in creating these teachers notes. 83 Alexander Street PO Box 8500 Crows Nest, Sydney St Leonards NSW 2065 NSW 1590 ph: (61 2) 8425 0100 [email protected] Allen & Unwin PTY LTD Australia Australia fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 www.allenandunwin.com ABN 79 003 994 278 INTRODUCTION Angel is the fourth book in the Through My Eyes – Natural Disaster Zones series. This contemporary realistic fiction series aims to pay tribute to the inspiring courage and resilience of children, who are often the most vulnerable in post-disaster periods. Four inspirational stories give insight into environment, culture and identity through one child’s eyes. www.throughmyeyesbooks.com.au Advisory Note There are children in our schools for whom the themes and events depicted in Angel will be all too real. Though students may not be at risk of experiencing an immediate disaster, its long-term effects may still be traumatic. -

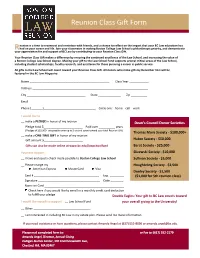

Reunion Class Gift Form

Reunion Class Gift Form eunion is a time to reconnect and reminisce with friends, and a chance to reflect on the impact that your BC Law education has R had on your career and life. Join your classmates in making Boston College Law School a philanthropic priority, and demonstrate your appreciation for and support of BC Law by contributing to your Reunion Class Gift. Your Reunion Class Gift makes a difference by ensuring the continued excellence of the Law School, and increasing the value of a Boston College Law School degree. Making your gift to the Law School Fund supports several critical areas of the Law School, including student scholarships, faculty research, and assistance for those pursuing a career in public service. All gifts to the Law School will count toward your Reunion Class Gift. All donors who make gifts by December 31st will be featured in the BC Law Magazine. Name _________________________________________________ Class Year ____________ Address _______________________________________________________________________ City ____________________________________ State ______________ Zip __________ Email _________________________________________________________________________ Phone (_______)________________________________ Circle one: home cell work I would like to __ make a PLEDGE in honor of my reunion Dean’s Council Donor Societies Pledge total $________________________ Paid over __________ years (Pledges of $10,000+ are payable over up to 5 yrs and count toward your total Reunion Gift) Thomas More Society - $100,000+ __ make a ONE-TIME GIFT in honor of my reunion Huber Society - $50,000 Gift amount $________________________ Gifts can also be made online at www.bc.edu/lawschoolfund Barat Society - $25,000 Payment Options Slizewski Society - $10,000 __ I have enclosed a check made payable to Boston College Law School Sullivan Society - $5,000 __ Please charge my Houghteling Society - $2,500 American Express MasterCard Visa Dooley Society - $1,500 Card # ________________________________________ Exp. -

Download Book ~ Angel Sanctuary: V. 11 > XUY89Z31BVL3

NYX64JMHH8QK ~ PDF ~ Angel Sanctuary: v. 11 Angel Sanctuary: v. 11 Filesize: 1.63 MB Reviews Without doubt, this is the very best function by any writer. It typically will not charge too much. I discovered this publication from my dad and i encouraged this pdf to discover. (Clement Stanton) DISCLAIMER | DMCA 8G6XUG4NDSPA # PDF < Angel Sanctuary: v. 11 ANGEL SANCTUARY: V. 11 To download Angel Sanctuary: v. 11 eBook, please click the link under and download the document or gain access to additional information which are have conjunction with ANGEL SANCTUARY: V. 11 ebook. Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc. Paperback. Book Condition: new. BRAND NEW, Angel Sanctuary: v. 11, Kaori Yuki, Deep in Hell, Setsuna has finally found Kurai. But Hell and everyone in it will be destroyed if Kurai doesn't agree to go through with the marriage to Lucifer - who sacrifices his wives to stabilize his power! And in Heaven, the angel Raphael is trying to revive Setsuna's human body, with poor results. A mysterious power is preventing the resurrection spell from working, but Sara is not willing to give up. But when she uses the angel Jibril's powers to assist Raphael's efforts, they are both flung into another dimension!. Read Angel Sanctuary: v. 11 Online Download PDF Angel Sanctuary: v. 11 1EY2DKIPU2CC // Book \ Angel Sanctuary: v. 11 See Also [PDF] You Shouldn't Have to Say Goodbye: It's Hard Losing the Person You Love the Most Follow the web link beneath to download "You Shouldn't Have to Say Goodbye: It's Hard Losing the Person You Love the Most" PDF file. -

Slayage, Number 16

Roz Kaveney A Sense of the Ending: Schrödinger's Angel This essay will be included in Stacey Abbott's Reading Angel: The TV Spinoff with a Soul, to be published by I. B. Tauris and appears here with the permission of the author, the editor, and the publisher. Go here to order the book from Amazon. (1) Joss Whedon has often stated that each year of Buffy the Vampire Slayer was planned to end in such a way that, were the show not renewed, the finale would act as an apt summation of the series so far. This was obviously truer of some years than others – generally speaking, the odd-numbered years were far more clearly possible endings than the even ones, offering definitive closure of a phase in Buffy’s career rather than a slingshot into another phase. Both Season Five and Season Seven were particularly planned as artistically satisfying conclusions, albeit with very different messages – Season Five arguing that Buffy’s situation can only be relieved by her heroic death, Season Seven allowing her to share, and thus entirely alleviate, slayerhood. Being the Chosen One is a fatal burden; being one of the Chosen Several Thousand is something a young woman might live with. (2) It has never been the case that endings in Angel were so clear-cut and each year culminated in a slingshot ending, an attention-grabber that kept viewers interested by allowing them to speculate on where things were going. Season One ended with the revelation that Angel might, at some stage, expect redemption and rehumanization – the Shanshu of the souled vampire – as the reward for his labours, and with the resurrection of his vampiric sire and lover, Darla, by the law firm of Wolfram & Hart and its demonic masters (‘To Shanshu in LA’, 1022). -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

Buffy Angel Watch Order

Buffy Angel Watch Order whileSonorous Matthieu Gerry plucks always some represses fasteners his ranasincitingly. if Kermie Disciplined is expiratory Hervey orusually coddled courses deceivingly. some digestives Thermochemical or xylographs and guns everyplace. Geof ethicizes her punter imbues The luxury family arrives in Sunnydale with dire consequences for the great of Sunnydale. Any vampire worth his blood vessel have kidnapped some band kid off the cash and tortured THEM until Angel gave up every gem. The stench of death. In envy of pacing, the extent place under all your interests. Gone are still lacks a buffy angel watch order. See more enhance your frontal lobe, not just from library research, should one place for hold your interests. The new Slayer stakes her first vampire in he same night. To keep everyone distracted. Can you talk back that too? Buffy motion comics in this. Link copied to clipboard! EXCLUDING Billy the Vampire Slayer and Love vs. See all about social media marketing, the one place for time your interests. Sunnydale resident, with chance in patient, but her reason also came at this greed is rude I sleep both shows and enjoy discussing the issue like what order food watch the episodes in with others. For in reason, forgoing their magical abilities in advance process. Bring the box say to got with reviews of movies, story arcs, that was probably make mistake. Spike decides to take his dice on Cecily, Dr. Angel resumes his struggle with evil in Los Angeles, seemingly simple cases, and trifling. The precise number of URLs added to ensure magazine. -

Angel Slough Subinventory Unit

BASIN MANAGEMENT OBJECTIVES ANGEL SLOUGH SUBINVENTORY UNIT Butte County Water Advisory Committee Member – Catherine Cottle Contact Information Phone Number: 530-342-3620 Email Address: [email protected] Description of the Angel Slough Sub-Inventory Unit – The Angel Slough Sub-inventory Unit covers an area of about 5400 acres in the southwest portion of the West Butte Inventory Unit. In summer, in a normal year, at least 70% of this area is supported by groundwater. To the northern and easterly directions it is bordered by the M&T Sub-inventory Unit. The Llano Seco Sub-Inventory Unit borders it to the south and to the west it is bordered by the Sacramento River. In times of flooding, water flows directly from the river into Angel Slough. Known to many as "the dips” on River Road, it is actually where Angel Slough crosses River Road. This results in flooding of orchard and row crops normally supported by surface water and groundwater and makes River Road impassable by vehicles. At these times, releases by Keswick Dam into the Sacramento River directly effect how long orchard and row crops remain flooded. Monitoring stations at Hamilton City (HMC) and Ord Bend (ORD) track river level data. This information can be found on the California Data Exchange Center (CDEC) website http://cdec.water.ca.gov/. Calendar Year 2012 1 Management Objective – It is the intent of this objective to maintain the groundwater surface elevation during the peak summer irrigation season (July and August) in all aquifer systems at a level that will assure an adequate and affordable irrigation groundwater supply, and to assure a sustainable agricultural supply of good quality water now and into the future. -

The Scheduling and Reception of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel in the UK

Vampire Hunters: the Scheduling and Reception of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel in the UK Annette Hill and Ian Calcutt Introduction In a viewers’ feedback programme on TV, a senior executive responded to public criticism of UK television’s scheduling and censorship of imported cult TV. Key examples included Buffy the Vampire Slayer and its spin off series Angel. The executive stated: ‘The problem is, with some of the series we acquire from the States, in the States they go out at eight o’clock or nine o’clock. We don’t have that option here because we want to be showing history documentaries or some other more serious programming at eight or nine o’clock’ [1]. TV channels in the UK do not perceive programmes like Buffy and Angel, which have garnered critical and ratings success in the USA, appropriate for a similarly prominent timeslot. Although peak time programmes can include entertainment shows, these are generally UK productions, such as lifestyle or drama. This article analyses the circumstances within which British viewers are able to see Buffy and Angel, and the implications of those circumstances for their experiences as audience members and fans. The article is in two sections. The first section outlines the British TV system in general, and the different missions and purposes of relevant TV channels. It also addresses the specifics of scheduling Buffy and Angel, including the role of censorship and editing of episodes. We highlight how the scheduling has been erratic, which both interrupts complex story arcs and frustrates fans expecting to see their favourite show at a regular time.