Importance of Litening Instruction, Providing Genpral Background Information Om the Nature of Listening

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Juntos Es Mejor

ARTICULOS OTOÑO 2020 BY GINA SHAW Juntos es mejor Cuando se le diagnosticó demencia a su esposo, la cantante Vikki Carr se convirtió en su cuidadora y aprendió lecciones valiosas sobre el amor y la salud. Fotografía por Randee St. Nicholas Durante casi 20 años, la tres veces ganadora del Grammy, Vikki Carr, disfrutó de una vida doméstica felizmente ordinaria con su esposo, Pedro De León, un médico de familia. “Nuestro tiempo juntos era increíble”, comenta la cantante. “De 5 a.m. a 7 p.m. atendía a sus pacientes; después, si teníamos algún evento, me decía: ‘Cariño, me ducho y estoy listo’. Y siempre lo estaba. Cuidó de mí”. Hasta que no pudo hacerlo más y entonces Carr intervino. La hermana de De León fue la primera en notar cambios en su conducta entre 2010 y 2011: se volvió olvidadizo, estaba confundido, y tenía problemas para prescribir recetas. “Ella era enfermera en su consultorio y estuvo con él durante casi 50 años, en la misma habitación todo el tiempo, así que ella lo detectó desde el inicio”, explica Carr. A principios de 2012, a los 82 años, De León fue diagnosticado formalmente con demencia. Pero Carr aún no lo aceptaba. “No podía ver lo que se avecinaba hasta que un día se sentó conmigo, me miró y dijo: ‘Te amo’, yo le respondí ‘Yo también te amo cariño’, pero entonces golpeó la mesa con el puño y me dijo enfáticamente: ‘Te amo y pase lo que pase conmigo, no quiero que nunca lo olvides’”. Carr, quien recibió el Lifetime Achievement Grammy de Latin Recording Academy en 2008, tomó un descanso del escenario para atender a su marido, quien murió el año pasado. -

United Artists Latino L 31000/LS-61000 Series

United Artists Latino L 31000/LS-61000 Series L-31001/LS-61005 –La Versatilidad de Freddie Rodriguez –Freddie Rodriguez [1968] Lolypop/Guajira Borincana/Don't Cry/No Me Pertenece/New York Is Boss/Banana Baby//Going Nowhere/Esta's En Nada/Lulu Boogaloo/Anoche Sone/Swing Para Ti (Part 1)/Swing Para Ti (Part 2) L-31002/LS-61002 –Presentanido a Mary Pacheco –Mary Pacheco [1968] Todas Mis Amigas/Otra Vez Adios/Con Llanto De Dios/Vas/Hoy/Johnny/Noche De Lluvia/Mas/Eres Todo Para Mi/En Un Rincon Del Alma/La Almohada/Tocame L-31003/LS-61003 –Silken Thread –Los Pekenikes [1968] Reissue of UA International UN 14515/UNS-15515. Hilo De Seda/Viaje Nocturno/La Vieja Fuente/Sombras Y Rejas/Troncos Huecos/Trapos Viejos//Lady Pepa/No Puedo Sentarme/Rimance Anonimo/Frente a Palacio/Ritmo De Conciertos/Arena Caliente LS-61004 –Al Ponerse El Sol –Raphael [1968] Al Ponerse El Sol/No Tiene Importancia/La Noche/Si Un Amor Se Va/Hasta Venecia/Yo Solo/Hablemos Del Amor/Es Verdad --Noche De Ronda/Siempre Estas En Mi Pensamiento/Volveras Otra Vez --Quedate Con Nosotros L-31005/LS-61005 –Concierto Para Bongo –Perez Prado [1969] Claudia/Virgen de La Macarena/Mamma a Go- Go/Estoy Acabando/Cayetano/Fantasia/Concierto Para Bongo 31006 L-31007/LS-61007 –Detras de Mi Sonrisa –Chucho Avellanet [1969] Canta Muchachita/Quedate/La Noche/Un Sueno Imposible - El Ideal/Hay Un Hombre/Sobre El Techo Azul De Mi Loco Amor/Amor Desesperado/Detras De Mi Sonrisa/Un Pobre Actor/El Mundo Cruel L-31008/LS-61008 - Tito Rodriguez Con Amor (With Love) - Tito Rodriguez [1969] Reissue of UAL-3326/UAS- 6326. -

Vikki Carr – Album and Single - (Born Florencia Bisenta De Casillas Martinez Cardona, July 19, 1941)

Vikki Carr – album and single - (born Florencia Bisenta de Casillas Martinez Cardona, July 19, 1941) She recorded about 30 singles for Liberty in the period: 1962 – 1970 – after that she went to Columbia Records. 1213 Carr, Vikki She’ll Be There/ Your Heart Is Free Just Like The Wind Liberty 56026 (US) 1968 No Leon on this one. Both prod. by Ron Bledsoe & Dave Peel. 1204 Carr, Vikki Don’t Break My Pretty Balloon/Nothing To Lose Liberty 56039 (US) 1968 No Leon on this one. Prod. by Ron Bledsoe & Dave Peel – 1: Arr. by Lincoln Mayorga – 2: Arr. by Bob Florence – Track 1 is from the hilarious Peter Sellers movie “The Party” (Title in Denmark: “Wash my Elephant”!) 1221 Carr, Vikki A Dissatisfied Man/Happy Together Liberty 56062 (US) 1968 Nice Leon like piano on 1 – no piano on 2 – Prod. by Ron Bledsoe & Dave Peel – 1: Arr. and conducted by Don Tweedy – 2: Arr. by Bob Florence 1079 Carr, Vikki Can’t Take My Eyes Off Of You/ With Pen In Hand Liberty 56092 (US) 1969 The piano on “With Pen in Hand” can only be Leon! It must be - even if it’s a late session for him. It ends with handclapping as if it was a live recording. Prod. Dave Pell & Ron Bledsoe – arr. Ernie Freeman. Track 1 has no Leon and is arr. by Ernie Freeman 1208 Carr, Vikki Eternity/I Will Wait For Love Liberty 56132 (US) 1969 No Leon on this one. There is a piano on 1, way back in the orchestra. -

Emergent Bilinguals in YPAR: Agency, Engagement

Running head: EMERGENT BILINGUALS IN YPAR EMERGENT BILINGUALS IN YPAR: AGENCY, ENGAGEMENT, TRANSLANGUAGING AND RELATIONSHIPS By LAURA M. ARREDONDO A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of Education Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education Graduate Program in Educational Leadership written under the direction of ________________________________ Dr. Beth C. Rubin ________________________________ Dr. Nicole Mirra ________________________________ Dr. Ariana Mangual Figueroa ________________________________ Dr. JoAnne Negrín New Brunswick, NJ May 2020 EMERGENT BILINGUALS IN YPAR © [2020] Laura M. Arredondo ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii EMERGENT BILINGUALS IN YPAR EXPERIENCES OF EMERGENT BILINGUALS IN A TRANSLANGUAGING YPAR SETTING Laura M. Arredondo ABSTRACT This phenomenological case study of emergent bilingual Latinx students in a suburban public high school district examined engagement and language use in a Youth Participatory Action Research curricular unit. This contrasts with more typical remediated learning experiences, which often result in disengagement, failure and dropout (Callahan, 2013; Menken, 2008; Scown, 2018). YPAR is an effective approach for increasing engagement through the validation of student knowledge, the inclusion of authentic learning, and the promotion of student agency (Cammarota and Fine, 2008; Mirra, Garcia and Morrell, 2016; Ozer & Wright, 2012). Translanguaging promotes student voice by validating student linguistic knowledge and providing a space where students are permitted to use their complete linguistic repertoires (Canagarajah, 2015; Garcia, 2017). For emergent bilingual Latinx students, traditional classrooms limit linguistic agency of students by prescribing the use of English and discouraging the use of Spanish, thus denying student voice and agency. This study sought to explore student experiences in a YPAR context where students had access to their complete linguistic repertoires. -

Ada Firemen to Shoot the Inorks Cascade's Celebration Set- Plans

'Lowell Ledger ft Suburhari Life 99 Covering Area Happening of People You Know! NEWSSTAND PRICE 10 cents VOL 79 NO. 13 TWO SECTIONS - JULY 1.1972 VOL 18 NO. 14 u A neighborhood Carnival against dystrophy will be held Thursday, July 6, Public Hearing July 5 th On Sewer Project at Richard's Park from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. The carnival will feature such games as Toss Across, Coin Toss, Fortune Moving their regular meeting date from July 3 to At that time. Council agreed to hold a public meeting Telling. Fish Pond, Basketball Throw, Fish Gallery, Ring the Pop, Unlock July 5, because of the holiday, the Lowell City Coun- when a further look at financing and the project itself the Chest, Clown and a raffle. cil will assemble in city hall on this date to again take had been made. up the issue of the somewhat controversial storm sewer All proceeds will go to aid the fight against muscular dystrophy and re- At the July 5th meeting. Mayor Carlen Anderson is lated diseases afflicting millions. project. expected to reveal the pertinent facts behind the favor- Meeting at 8 p.m., the public hearing, open to all in- Neighborhood Sponsoring the event is the TaWaAya Camp Fire Girls-Amy Steward, Doro- able indications that have been received, indicating that thy Burton, Debbie Kinyon, Carol Scharaswak, Anna Miller, JoAnn Keim, terested citizens, will discuss the financing of the pro- sufficient aid will be forthcoming to allow the city to ject. and Laurie McMahon, and the newly formed Horizon Club-Cindy Butts, go "full speed" ahead on the project. -

MCA Discography

MCA-1 Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan MCA Discography Note: When MCA discontinued Decca, Uni, Kapp and their subsidiary labels in late 1972, they started the new MCA label by consolidating artists from those old labels into the new label. Starting in 1973, MCA reissued hundreds of albums from all of those labels with new catalog numbers under the new MCA imprint. They started these reissues in the MCA-1 reissue series, which ran to MCA-299. MCA MCA-1 Reissue Series: MCA 1 - Loretta Lynn’s Greatest Hits - Loretta Lynn [1973] Reissue of Decca DL7 5000. Don't Come Home A Drinkin'/Before I'm Over You/If You're Not Gone Too Long/Dear Uncle Sam/Other Woman/Wine Women And Song//You Ain't Woman Enough/Blue Kentucky Girl/Success/Home You're Tearin' Down/Happy Birthday MCA 2 - This Is Jerry Wallace - Jerry Wallace [1973] Reissue of Decca DL7 5294. After You/She'll Remember/The Greatest Love/In The Misty Moonlight/New Orleans In The Rain/Time//The Morning After/I Can't Take It Any More/The Hands Of The Man/To Get To You/There She Goes MCA 3 - Rick Nelson in Concert - Rick Nelson [1973] Reissue of Decca DL7 5162. Come On In/Hello Mary Lou, Goodbye Heart/Violets Of Dawn/Who Cares About Tomorrow-Promises/She Belongs To Me/If You Gotta Go, Go Now//I'm Walkin'/Red Balloon/Louisiana Man/Believe What You Say/Easy To Be Free/I Shall Be Released MCA 4 - Sousa Marches in Hi-Fi - Goldman Band [1973] Reissue of Decca DL7 8807. -

1 POETRY, PROSE and SHORT FICTION for CREATIVITY-BASED CURRICULUM GUIDEBOOK on IMMIGRATION Javier Zamora

POETRY, PROSE AND SHORT FICTION FOR CREATIVITY-BASED CURRICULUM GUIDEBOOK ON IMMIGRATION “Just as when I started writing poetry, we’re at a very crucial time in American history and in planetary history…Poetry is a way to bridge, to make bridges from one country to another, one person to another, one time to another.” -Joy Harjo (2019, June 6) Javier Zamora …………………………………………………………………………. 2/290 Naomi Shihab Nye (excerpts from interview with Krista Tippett) ………………..….. 3/291 Justen Ahren (poetry, photos, stories from refugees in Levos, Greece) ………………. 8/296 Joanna Wróblewska (poetry and stories from refugees in Europe) ………………….. 19/307 Elizabeth McKim …………………………………………………………………….. 20/308 Meg Braley …………………………………………………………………………… 21/309 M. Soledad Caballero …………………………………………………………………. 23/311 Elexia Alleyne………………………………………………………………………… 24/312 Camille T. Dungy …………………………………………………………………….. 25/313 Hieu Minh Nguyen …………………………………………………………………… 26/314 Scott Ruescher ……………………………………………………………………….. 27/315 Ifrah Mansour …………………………………………………………………………..30/318 Sally Wen Mao ……………………………………………………………………….. 32/320 Courtesy of Split This Rock’s The Quarry: A Social Justice Poetry Database Odette Amaranta Vélez Valcárcel ……………………………………………………. 33/321 (Thoughts on Poetic Sensibility) In Spanish and English María Cristina Rojas …………………………………………………………………… 36/324 (thoughts on language and teaching through poetry) Women and Children in Detention Trilogy Nightmares and Dreams: Immigrant Voices from Inside Detention Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………. 37/325 Leaving -

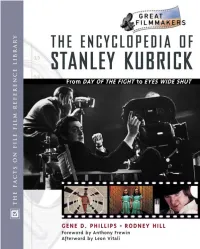

The Encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick

THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF STANLEY KUBRICK THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF STANLEY KUBRICK GENE D. PHILLIPS RODNEY HILL with John C.Tibbetts James M.Welsh Series Editors Foreword by Anthony Frewin Afterword by Leon Vitali The Encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick Copyright © 2002 by Gene D. Phillips and Rodney Hill All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hill, Rodney, 1965– The encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick / Gene D. Phillips and Rodney Hill; foreword by Anthony Frewin p. cm.— (Library of great filmmakers) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4388-4 (alk. paper) 1. Kubrick, Stanley—Encyclopedias. I. Phillips, Gene D. II.Title. III. Series. PN1998.3.K83 H55 2002 791.43'0233'092—dc21 [B] 2001040402 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Erika K.Arroyo Cover design by Nora Wertz Illustrations by John C.Tibbetts Printed in the United States of America VB FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 4000-4299

RCA Discography Part 13 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 4000-4299 LSP 4000 – All Time Christmas Hits – Piano Rolls and Voices by Dick Hyman [1968] Winter Wonderland/Silver Bells/It's Beginning To Look Like Christmas/Sleighride/The Christmas Song/I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus/Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow!/The Chipmunk Song/All I Want For Christmas Is My Two Front Teeth/Frosty The Snow Man/White Christmas LSP 4001 – Cool Crazy Christmas – Homer and Jethro [1968] Nuttin' Fer Christmas/Frosty The Snowman/I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus/Santa Claus, The Original Hippie/All I Want For Christmas Is My Upper Plate/Ornaments/The Night Before Christmas/Jingle Bells/Randolph The Flat-Nosed Reindeer/Santa Baby/Santa's Movin' On/The Nite After Christmas LPM/LSP 4002 – I Love Charley Brown – Connie Smith [1968] Run Away Little Tears/The Sunshine Of My World/That's All This Old World Needs/Little Things/If The Whole World Stopped Lovin'/Don't Feel Sorry For Me/I Love Charley Brown/Burning A Hole In My Mind/Baby's Back Again/Let Me Help You Work It Out/Between Each Tear/There Are Some Things LPM/LSP 4003 – The Wild Eye (Soundtrack) – Gianni Marchetti [1968] Two Lovers/The Desert/Meeting With Barbara/The Kiss/Two Lovers/Bali Street/Don't Go Away/The Sultan/All The Little Pictures/The End Of The Orient/Love Comes Back/Nights In Saigon/The Letter/Life Goes On/Useless Words/The Statue/Golden Age/Goodbye/I Love You LSP 4004 – Country Girl – Dottie West [1968] -

The Mississippi Mass Choir

R & B BARGAIN CORNER Bobby “Blue” Bland “Blues You Can Use” CD MCD7444 Get Your Money Where You Spend Your Time/Spending My Life With You/Our First Feelin's/ 24 Hours A Day/I've Got A Problem/Let's Part As Friends/For The Last Time/There's No Easy Way To Say Goodbye James Brown "Golden Hits" CD M6104 Hot Pants/I Got the Feelin'/It's a Man's Man's Man's World/Cold Sweat/I Can't Stand It/Papa's Got A Brand New Bag/Feel Good/Get on the Good Foot/Get Up Offa That Thing/Give It Up or Turn it a Loose Willie Clayton “Gifted” CD MCD7529 Beautiful/Boom,Boom, Boom/Can I Change My Mind/When I Think About Cheating/A LittleBit More/My Lover My Friend/Running Out of Lies/She’s Holding Back/Missing You/Sweet Lady/ Dreams/My Miss America/Trust (featuring Shirley Brown) Dramatics "If You come Back To Me" CD VL3414 Maddy/If You Come Back To Me/Seduction/Scarborough Faire/Lady In Red/For Reality's Sake/Hello Love/ We Haven't Got There Yet/Maddy(revisited) Eddie Floyd "Eddie Loves You So" CD STAX3079 'Til My Back Ain't Got No Bone/Since You Been Gone/Close To You/I Don't Want To Be With Nobody But You/You Don't Know What You Mean To Me/I Will Always Have Faith In You/Head To Toe/Never Get Enough of Your Love/You're So Fine/Consider Me Z. Z. -

Thanks to John Frank of Oakland, California for Transcribing and Compiling These 1960S WAKY Surveys!

Thanks to John Frank of Oakland, California for transcribing and compiling these 1960s WAKY Surveys! WAKY TOP FORTY JANUARY 30, 1960 1. Teen Angel – Mark Dinning 2. Way Down Yonder In New Orleans – Freddy Cannon 3. Tracy’s Theme – Spencer Ross 4. Running Bear – Johnny Preston 5. Handy Man – Jimmy Jones 6. You’ve Got What It Takes – Marv Johnson 7. Lonely Blue Boy – Steve Lawrence 8. Theme From A Summer Place – Percy Faith 9. What Did I Do Wrong – Fireflies 10. Go Jimmy Go – Jimmy Clanton 11. Rockin’ Little Angel – Ray Smith 12. El Paso – Marty Robbins 13. Down By The Station – Four Preps 14. First Name Initial – Annette 15. Pretty Blue Eyes – Steve Lawrence 16. If I Had A Girl – Rod Lauren 17. Let It Be Me – Everly Brothers 18. Why – Frankie Avalon 19. Since You Broke My Heart – Everly Brothers 20. Where Or When – Dion & The Belmonts 21. Run Red Run – Coasters 22. Let Them Talk – Little Willie John 23. The Big Hurt – Miss Toni Fisher 24. Beyond The Sea – Bobby Darin 25. Baby You’ve Got What It Takes – Dinah Washington & Brook Benton 26. Forever – Little Dippers 27. Among My Souvenirs – Connie Francis 28. Shake A Hand – Lavern Baker 29. It’s Time To Cry – Paul Anka 30. Woo Hoo – Rock-A-Teens 31. Sand Storm – Johnny & The Hurricanes 32. Just Come Home – Hugo & Luigi 33. Red Wing – Clint Miller 34. Time And The River – Nat King Cole 35. Boogie Woogie Rock – [?] 36. Shimmy Shimmy Ko-Ko Bop – Little Anthony & The Imperials 37. How Will It End – Barry Darvell 38. -

The River Weekly News Will Correct Factual Errors Or Matters of Emphasis and Interpretation That Appear in News Stories

FREE Take Me Read Us Online at Home IslandSunNews.com VOL. 10, NO. 26 From the Beaches to the River District downtown Fort Myers JULY 8, 2011 A Favorite Orphan Comes To Celebrity Guest Auctioneers Broadway Palm Theatre This Summer For ACT Graffiti Night roadway Palm Dinner Theatre pres- he guest celebrity auctioneer at ents the musical Annie playing July Arts for ACT’s fine art auction B7 through August 13. The story of Tand gala will be Bill Cobbs, an the lovable orphan and her dog Sandy American film and television actor, has been capturing the hearts of audience along with special guest, singer Bobby members for years. Goldsboro. As part of a publicity campaign for Titled Graffiti Night, this is the 24th Oliver Warbucks, Annie and her dog Sandy annual Arts for ACT fundraiser benefit- are placed in the lap of luxury for a week. ting Abuse Counseling and Treatment, However, Annie’s stay turns out to be Inc., the domestic violence, sexual much more than anyone had bargained assault and human trafficking center for as she works her way into everyone’s serving Lee, Hendry and Glades coun- hearts and learns a few things for herself. ties. Doors open at 5:30 p.m. The classic songs include It’s the Hard Stephanie Davis, the Downtown Knock Life, Easy Street and Tomorrow. Diva, will welcome guest and take pho- Annie will play at Broadway Palm tos with the “who’s who” of the Fort Dinner Theatre July 7 through August 13. Myers area. Performances are Wednesday through More than 70 silent auction artworks Sunday evenings with selected matinees.