PHYSIOLOGICAL ADAPTATION to NUTRIENT LIMITATION in a MARINE OLIGOTROPHIC ULTRAMICROBACTERIUM Sphingopyxis Alaskensis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emendation of the Genus Sphingomonas Yabuuchi Et Al

International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology (2002), 52, 1485–1496 DOI: 10.1099/ijs.0.01868-0 Emendation of the genus Sphingomonas Yabuuchi et al. 1990 and junior objective synonymy of the species of three genera, Sphingobium, Novosphingobium and Sphingopyxis, in conjunction with Blastomonas ursincola 1 Department of Eiko Yabuuchi,1 Yoshimasa Kosako,2 Nagatoshi Fujiwara,3 Microbiology, Gifu 3,4 5 5 University School of Takashi Naka, Isamu Matsunaga, Hisashi Ogura and Medicine, Tsukasa-machi Kazuo Kobayashi3 40, Gifu 500-8705, Japan 2 Japan Collection of Microorganisms, Institute Author for correspondence: Kazuo Kobayashi. Tel: j81 6 6645 3745. Fax: j81 6 6646 3662. of Physical and Chemical e-mail: kobayak!med.osaka-cu.ac.jp Research (RIKEN), Wako- shi, Saitama 351-0198, Japan The 16S rDNA sequence similarities between the type strains of Sphingomonas 3 Department of Host paucimobilis and 32 other Sphingomonas species range from 902to996%. It Defense, Osaka City might be possible to divide the genus into several new genera according to a University Graduate School dendrogram drawn from 16S rDNA sequence similarity. However, the of Medicine, 1-4-3 Asahi- machi, Abeno-ku, Osaka phenotypic and biochemical information needed to define clusters of strains 545-8585, Japan representing distinct genera within this group of organisms was not 4 Institute of Skin Sciences, previously available. Although the cellular lipids of type strains of all 28 Club Cosmetics Co. Ltd, Sphingomonas species tested contained glucuronosyl-(1 ! 1)-ceramide Ikoma-shi, Nara 630-0222, together with 2-hydroxymyristic acid, other molecular species of Japan sphingoglycolipids were distributed randomly. -

The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks Bioblitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 ON THIS PAGE Photograph of BioBlitz participants conducting data entry into iNaturalist. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service. ON THE COVER Photograph of BioBlitz participants collecting aquatic species data in the Presidio of San Francisco. Photograph courtesy of National Park Service. The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 Elizabeth Edson1, Michelle O’Herron1, Alison Forrestel2, Daniel George3 1Golden Gate Parks Conservancy Building 201 Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94129 2National Park Service. Golden Gate National Recreation Area Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1061 Sausalito, CA 94965 3National Park Service. San Francisco Bay Area Network Inventory & Monitoring Program Manager Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1063 Sausalito, CA 94965 March 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

Consistent Responses of Soil Microbial Communities to Elevated Nutrient Inputs in Grasslands Across the Globe

Consistent responses of soil microbial communities to elevated nutrient inputs in grasslands across the globe Jonathan W. Leffa,b, Stuart E. Jonesc, Suzanne M. Proberd, Albert Barberána, Elizabeth T. Borere, Jennifer L. Firnf, W. Stanley Harpoleg,h,i, Sarah E. Hobbiee, Kirsten S. Hofmockelj, Johannes M. H. Knopsk, Rebecca L. McCulleyl, Kimberly La Pierrem, Anita C. Rischn, Eric W. Seabloomo, Martin Schützn, Christopher Steenbockb, Carly J. Stevensp, and Noah Fierera,b,1 aCooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309; bDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309; cDepartment of Biological Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556; dCommonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation Land and Water Flagship, Wembley, WA 6913, Australia; eDepartment of Ecology, Evolution and Behavior, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN 55108; fSchool of Earth, Environmental and Biological Sciences, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD 4001, Australia; gDepartment of Physiological Diversity, Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research UFZ, 04318 Leipzig, Germany; hGerman Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research Halle-Jena-Leipzig, D-04103 Leipzig, Germany; iInstitute of Biology, Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, 06108 Halle (Saale), Germany; jEcology, Evolution, and Organismal Biology Department, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011; kSchool of Biological Sciences, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE 68588; lDepartment of Plant and Soil Sciences, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40546; mDepartment of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; nCommunity Ecology, Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research, 8903 Birmensdorf, Switzerland; oDepartment of Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN 55108; and pLancaster Environment Centre, Lancaster University, Lancaster, LA1 4YQ, United Kingdom Edited by Peter M. -

OUR PLACE in the UNIVERSE DR CHARLES Lineweaver

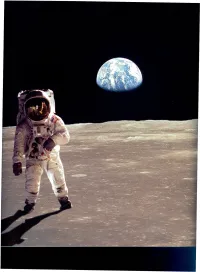

• I. WHERE ARE WE? Fig. 5b Earth from Moon with astronaut in foreground. In a canoe called the Earth, we are drifting down an unknown river. We Courtesy NASA (68·H·1401 and ASll-40-5903) What lies around the next bend? Some of us hear an ominous roar ahead - a water~ Some of us see the stream broadening and an immense unknown ocean on the horizon. We are on a journey through time. We may encounter other life forms or there may be j OrCharles Lineweaver is an billions of lifeless shores. We paddle and stab at the water trying to avoid jutting Australian Research Fellow in the School of Physics at the University of New South Wales. boulders and eddies. Many of us are bailing. We bail for about 80 years, then we give He studied undergraduate physics at Ludwig Maximillian Universitat, Germany and at our scoops and paddles to our children. If our canoe holds - if we can see far enough Kyoto University, Japan. He obtained his PhD from the University of California at ahead to avoid waterfalls and whirlpools, then surely our children's children's children... Berkeley for research on COBE satellite observations of the cosmic microwave background. will live to see this river empty into a placid infinite ocean. In the dark of the night, we After a postdoctoral fellowship in Strasbourg, France, he came gaze at the heavens and wonder who we are. How did we get on this canoe? to UNSWin 1997. He speaks four languages and has played semi· professional soccer. -

The Trophic-Dynamic Aspect of Ecology Author(S): Raymond L

The Trophic-Dynamic Aspect of Ecology Author(s): Raymond L. Lindeman Reviewed work(s): Source: Ecology, Vol. 23, No. 4 (Oct., 1942), pp. 399-417 Published by: Ecological Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1930126 . Accessed: 30/01/2012 10:50 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Ecological Society of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Ecology. http://www.jstor.org THE TROPHIC-DYNAMIC ASPECT OF ECOLOGY RAYMOND L. LINDEMAN OsbornZoological Laboratory,Yale University Recent progressin the studyof aquatic community. A more "bio-ecological" food-cycle relationships invites a re- species-distributionalapproach would appraisal of certain ecological tenets. recognize both the plants and animals Quantitative productivitydata provide as co-constituentsof restricted"biotic" a basis for enunciating certain trophic communities,such as "plankton com- principles, which, when applied to a munities," "benthic communities,"etc., series of successional stages, shed new in which membersof the living commu- light on the dynamics of ecological nity "co-act" with each other and "re- succession. act" with the non-livingenvironment (Clementsand Shelford,'39; Carpenter, "COMMUNITY" CONCEPTS '39, '40; T. Park, '41). -

Light in and Sound Out: Emerging Translational Strategies for Photoacoustic Imaging

Published OnlineFirst February 10, 2014; DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2387 Cancer Review Research Light In and Sound Out: Emerging Translational Strategies for Photoacoustic Imaging S. Zackrisson1,2,3,4,5, S.M.W.Y. van de Ven1,2,3,4, and S.S. Gambhir1,2,3,4 Abstract Photoacoustic imaging (PAI) has the potential for real-time molecular imaging at high resolution and deep inside the tissue, using nonionizing radiation and not necessarily depending on exogenous imaging agents, making this technique very promising for a range of clinical applications. The fact that PAI systems can be made portable and compatible with existing imaging technologies favors clinical translation even more. The breadth of clinical applications in which photoacoustics could play a valuable role include: noninvasive imaging of the breast, sentinel lymph nodes, skin, thyroid, eye, prostate (transrectal), and ovaries (transvaginal); minimally invasive endoscopic imaging of gastrointestinal tract, bladder, and circulating tumor cells (in vivo flow cytometry); and intraoperative imaging for assessment of tumor margins and (lymph node) metastases. In this review, we describe the basics of PAI and its recent advances in biomedical research, followed by a discussion of strategies for clinical translation of the technique. Cancer Res; 74(4); 979–1004. Ó2014 AACR. Introduction In this review, we will first describe the basics of PAI, Photoacoustic imaging (PAI), also referred to as optoacous- followed by a comprehensive overview of its clinical applica- tic imaging, is an emerging new imaging technique with tions. We will then discuss strategies for future translation to significant promise for biomedical applications. The key clinical practice. -

Table S5. the Information of the Bacteria Annotated in the Soil Community at Species Level

Table S5. The information of the bacteria annotated in the soil community at species level No. Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species The number of contigs Abundance(%) 1 Firmicutes Bacilli Bacillales Bacillaceae Bacillus Bacillus cereus 1749 5.145782459 2 Bacteroidetes Cytophagia Cytophagales Hymenobacteraceae Hymenobacter Hymenobacter sedentarius 1538 4.52499338 3 Gemmatimonadetes Gemmatimonadetes Gemmatimonadales Gemmatimonadaceae Gemmatirosa Gemmatirosa kalamazoonesis 1020 3.000970902 4 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas indica 797 2.344876284 5 Firmicutes Bacilli Lactobacillales Streptococcaceae Lactococcus Lactococcus piscium 542 1.594633558 6 Actinobacteria Thermoleophilia Solirubrobacterales Conexibacteraceae Conexibacter Conexibacter woesei 471 1.385742446 7 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas taxi 430 1.265115184 8 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas wittichii 388 1.141545794 9 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas sp. FARSPH 298 0.876754244 10 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sorangium cellulosum 260 0.764953367 11 Proteobacteria Deltaproteobacteria Myxococcales Polyangiaceae Sorangium Sphingomonas sp. Cra20 260 0.764953367 12 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas panacis 252 0.741416341 -

Deliverable D.8.3 Literature Review of On-Line Bioprocess Monitoring

NANOBE SEVENTH FRAMEWORK PROGRAMME THEME 2 Food, Agriculture and Fisheries, and Biotechnology Grant Agreement no: 227243 Project acronym: NANOBE Project title: Nano- and microtechnology –based analytical devices for online measurements of bioprocesses Funding Scheme: CA Deliverable D.8.3 Literature review of on-line bioprocess monitoring Report Due date of delivery: Month 18 Actual date of delivery: November 26th 2010 Responsible authors: Juha-Pekka Pitkänen (VTT), Heidi Turkia (VTT) Co-operative authors: Heli Sirén (VTT), Anna Rissanen (VTT), Guillaume Mernier (EPFL), Frédéric Reymond (DiagnoSwiss), Karen Lemke (iba), Francois Brunelle (CNRS-IEMN), Päivi Heimala (VTT) Project co-funded by the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme FP7 (2007-2013) Dissemination level PU Public PU PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission RE Services) Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission CO Services) Deliverable D.8.3 NANOBE GA no. 227243 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 1 SUMMARY 3 2 PURPOSE AND SCOPE 3 3 INTRODUCTION 3 4 MEASUREMENT APPROACHES 8 4.1 Optical measurements 8 4.1.1 Optical single point measurements 8 4.1.2 Imaging measurements 9 4.2 Electrical measurements 10 4.3 Measurements based on chromatography-like separation 12 4.3.1 On-line capillary electrophoresis 12 4.3.2 On-line liquid chromatography 12 4.3.3 On-line gas chromatography 14 4.4 Direct mass spectrometric measurements 14 4.5 Measurements where biological component aids in recognition 15 5 SAMPLING AND SAMPLE TREATMENT APPROACHES 15 5.1 Automated sampling 16 5.2 Sample fractionation 18 5.3 Cell lysis 18 6 CONCLUSIONS 19 7 REFERENCES 19 2/25 Deliverable D.8.3 NANOBE GA no. -

(Antarctica) Glacial, Basal, and Accretion Ice

CHARACTERIZATION OF ORGANISMS IN VOSTOK (ANTARCTICA) GLACIAL, BASAL, AND ACCRETION ICE Colby J. Gura A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2019 Committee: Scott O. Rogers, Advisor Helen Michaels Paul Morris © 2019 Colby Gura All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Scott O. Rogers, Advisor Chapter 1: Lake Vostok is named for the nearby Vostok Station located at 78°28’S, 106°48’E and at an elevation of 3,488 m. The lake is covered by a glacier that is approximately 4 km thick and comprised of 4 different types of ice: meteoric, basal, type 1 accretion ice, and type 2 accretion ice. Six samples were derived from the glacial, basal, and accretion ice of the 5G ice core (depths of 2,149 m; 3,501 m; 3,520 m; 3,540 m; 3,569 m; and 3,585 m) and prepared through several processes. The RNA and DNA were extracted from ultracentrifugally concentrated meltwater samples. From the extracted RNA, cDNA was synthesized so the samples could be further manipulated. Both the cDNA and the DNA were amplified through polymerase chain reaction. Ion Torrent primers were attached to the DNA and cDNA and then prepared to be sequenced. Following sequencing the sequences were analyzed using BLAST. Python and Biopython were then used to collect more data and organize the data for manual curation and analysis. Chapter 2: As a result of the glacier and its geographic location, Lake Vostok is an extreme and unique environment that is often compared to Jupiter’s ice-covered moon, Europa. -

Sphingopyxis Italica, Sp. Nov., Isolated from Roman Catacombs 1 2

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE IJSEM Papers in Press. Published December 21, 2012 as doi:10.1099/ijs.0.046573-0 provided by Digital.CSIC 1 Sphingopyxis italica, sp. nov., isolated from Roman catacombs 2 3 Cynthia Alias-Villegasª, Valme Jurado*ª, Leonila Laiz, Cesareo Saiz-Jimenez 4 5 Instituto de Recursos Naturales y Agrobiologia, IRNAS-CSIC, 6 Apartado 1052, 41080 Sevilla, Spain 7 8 * Corresponding author: 9 Valme Jurado 10 Instituto de Recursos Naturales y Agrobiologia, IRNAS-CSIC 11 Apartado 1052, 41080 Sevilla, Spain 12 Tel. +34 95 462 4711, Fax +34 95 462 4002 13 E-mail: [email protected] 14 15 ª These authors contributed equally to this work. 16 17 Keywords: Sphingopyxis italica, Roman catacombs, rRNA, sequence 18 19 The sequence of the 16S rRNA gene from strain SC13E-S71T can be accessed 20 at Genbank, accession number HE648058. 21 22 A Gram-negative, aerobic, motile, rod-shaped bacterium, strain SC13E- 23 S71T, was isolated from tuff, the volcanic rock where was excavated the 24 Roman Catacombs of Saint Callixtus in Rome, Italy. Analysis of 16S 25 rRNA gene sequences revealed that strain SC13E-S71T belongs to the 26 genus Sphingopyxis, and that it shows the greatest sequence similarity 27 with Sphingopyxis chilensis DSMZ 14889T (98.72%), Sphingopyxis 28 taejonensis DSMZ 15583T (98.65%), Sphingopyxis ginsengisoli LMG 29 23390T (98.16%), Sphingopyxis panaciterrae KCTC12580T (98.09%), 30 Sphingopyxis alaskensis DSM 13593T (98.09%), Sphingopyxis 31 witflariensis DSM 14551T (98.09%), Sphingopyxis bauzanensis DSM 32 22271T (98.02%), Sphingopyxis granuli KCTC12209T (97.73%), 33 Sphingopyxis macrogoltabida KACC 10927T (97.49%), Sphingopyxis 34 ummariensis DSM 24316T (97.37%) and Sphingopyxis panaciterrulae T 35 KCTC 22112 (97.09%). -

Short-Term Rhizosphere Effect on Available Carbon Sources

Short-Term Rhizosphere Effect on Available Carbon Sources, Phenanthrene Degradation, and Active Microbiome in an Aged-Contaminated Industrial Soil François Thomas, Aurélie Cebron To cite this version: François Thomas, Aurélie Cebron. Short-Term Rhizosphere Effect on Available Carbon Sources, Phenanthrene Degradation, and Active Microbiome in an Aged-Contaminated Industrial Soil. Fron- tiers in Microbiology, Frontiers Media, 2016, 7, pp.92. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00092. hal-01780413 HAL Id: hal-01780413 https://hal.univ-lorraine.fr/hal-01780413 Submitted on 29 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 05 February 2016 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00092 Short-Term Rhizosphere Effect on Available Carbon Sources, Phenanthrene Degradation, and Active Microbiome in an Aged-Contaminated Industrial Soil François Thomas 1, 2 † and Aurélie Cébron 1, 2* 1 CNRS, LIEC UMR7360, Faculté des Sciences et Technologies, Vandoeuvre-lés-Nancy, France, 2 Université de Lorraine, LIEC UMR7360, Faculté des Sciences et Technologies, Vandoeuvre-lés-Nancy, France Edited by: Dimitrios Georgios Karpouzas, Over the last decades, understanding of the effects of plants on soil microbiomes has University of Thessaly, Greece greatly advanced. However, knowledge on the assembly of rhizospheric communities in Reviewed by: Antonis Chatzinotas, aged-contaminated industrial soils is still limited, especially with regard to transcriptionally Helmholtz Centre for Environmental active microbiomes and their link to the quality or quantity of carbon sources. -

Spatial Ecology of Territorial Populations

Spatial ecology of territorial populations Benjamin G. Weinera, Anna Posfaib, and Ned S. Wingreenc,1 aDepartment of Physics, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544; bSimons Center for Quantitative Biology, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY 11724; and cLewis–Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544 Edited by Nigel Goldenfeld, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Urbana, IL, and approved July 30, 2019 (received for review July 9, 2019) Many ecosystems, from vegetation to biofilms, are composed of and penalize niche overlap (25), but did not otherwise struc- territorial populations that compete for both nutrients and phys- ture the spatial interactions. All these models allow coexistence ical space. What are the implications of such spatial organization when the combination of spatial segregation and local interac- for biodiversity? To address this question, we developed and ana- tions weakens interspecific competition relative to intraspecifc lyzed a model of territorial resource competition. In the model, competition. However, it remains unclear how such interactions all species obey trade-offs inspired by biophysical constraints on relate to concrete biophysical processes. metabolism; the species occupy nonoverlapping territories, while Here, we study biodiversity in a model where species interact nutrients diffuse in space. We find that the nutrient diffusion through spatial resource competition. We specifically consider time is an important control parameter for both biodiversity and surface-associated populations which exclude each other as they the timescale of population dynamics. Interestingly, fast nutri- compete for territory. This is an appropriate description for ent diffusion allows the populations of some species to fluctuate biofilms, vegetation, and marine ecosystems like mussels (28) or to zero, leading to extinctions.