Becoming Paul M. Churchland (1942–) 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dualism Vs. Materialism: a Response to Paul Churchland

Dualism vs. Materialism: A Response to Paul Churchland by M. D. Robertson Paul M. Churchland, in his book, Matter and Consciousness, provides a survey of the issues and positions associated with the mind-body problem. This problem has many facets, and Churchland addresses several of them, including the metaphysical, epistemological, semantic, and methodological aspects of the debate. Churchland, of course, has very strong views on the subject, and does not hide his biases on the matter. In this paper I shall reexamine the metaphysical aspect of the mind-body problem. The metaphysical question concerns the existential status of the mind and the body, and the nature of the relationship between them. Like Churchland, I shall not hide my biases on the matter. What follows may be thought of as a rewriting of the second chapter of Churchland's book ("The Ontological Issue") from a non-naturalistic perspective. Substance Dualism René Descartes argued that the defining characteristic of minds was cogitation in a broad 2 sense, while that of bodies was spatial extension. Descartes also claimed that minds were not spatially extended, nor did bodies as such think. Thus minds and bodies were separate substances. This view has come to be called substance dualism. Descartes's argument for substance dualism can be summarized as follows: (1) Minds exist. (2) Bodies exist. (3) The defining feature of minds is cogitation. (4) The defining feature of bodies is extension. (5) That which cogitates is not extended. (6) That which is extended does not cogitate. Therefore, (7) Minds are not bodies, and bodies are not minds. -

Curriculum Vitae

BAS C. VAN FRAASSEN Curriculum Vitae Last updated 3/6/2019 I. Personal and Academic History .................................................................................................................... 1 List of Degrees Earned ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Title of Ph.D. Thesis ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 Positions held ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Invited lectures and lecture series ........................................................................................................................................ 1 List of Honors, Prizes ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Research Grants .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Non-Academic Publications ................................................................................................................................................ 5 II. Professional Activities ................................................................................................................................. -

In Defence of Folk Psychology

FRANK JACKSON & PHILIP PETTIT IN DEFENCE OF FOLK PSYCHOLOGY (Received 14 October, 1988) It turned out that there was no phlogiston, no caloric fluid, and no luminiferous ether. Might it turn out that there are no beliefs and desires? Patricia and Paul Churchland say yes. ~ We say no. In part one we give our positive argument for the existence of beliefs and desires, and in part two we offer a diagnosis of what has misled the Church- lands into holding that it might very well turn out that there are no beliefs and desires. 1. THE EXISTENCE OF BELIEFS AND DESIRES 1.1. Our Strategy Eliminativists do not insist that it is certain as of now that there are no beliefs and desires. They insist that it might very well turn out that there are no beliefs and desires. Thus, in order to engage with their position, we need to provide a case for beliefs and desires which, in addition to being a strong one given what we now know, is one which is peculiarly unlikely to be undermined by future progress in neuroscience. Our first step towards providing such a case is to observe that the question of the existence of beliefs and desires as conceived in folk psychology can be divided into two questions. There exist beliefs and desires if there exist creatures with states truly describable as states of believing that such-and-such or desiring that so-and-so. Our question, then, can be divided into two questions. First, what is it for a state to be truly describable as a belief or as a desire; what, that is, needs to be the case according to our folk conception of belief and desire for a state to be a belief or a desire? And, second, is what needs to be the case in fact the case? Accordingly , if we accepted a certain, simple behaviourist account of, say, our folk Philosophical Studies 59:31--54, 1990. -

Maintaining Meaningful Expressions of Romantic Love in a Material World

Reconciling Eros and Neuroscience: Maintaining Meaningful Expressions of Romantic Love in a Material World by ANDREW J. PELLITIERI* Boston University Abstract Many people currently working in the sciences of the mind believe terms such as “love” will soon be rendered philosophically obsolete. This belief results from a common assumption that such terms are irreconcilable with the naturalistic worldview that most modern scientists might require. Some philosophers reject the meaning of the terms, claiming that as science progresses words like ‘love’ and ‘happiness’ will be replaced completely by language that is more descriptive of the material phenomena taking place. This paper attempts to defend these meaningful concepts in philosophy of mind without appealing to concepts a materialist could not accept. Introduction hilosophy engages the meaning of the word “love” in a myriad of complex discourses ranging from ancient musings on happiness, Pto modern work in the philosophy of mind. The eliminative and reductive forms of materialism threaten to reduce the importance of our everyday language and devalue the meaning we attach to words like “love,” in the name of scientific progress. Faced with this threat, some philosophers, such as Owen Flanagan, have attempted to defend meaningful words and concepts important to the contemporary philosopher, while simultaneously promoting widespread acceptance of materialism. While I believe that the available work is useful, I think * [email protected]. Received 1/2011, revised December 2011. © the author. Arché Undergraduate Journal of Philosophy, Volume V, Issue 1: Winter 2012. pp. 60-82 RECONCILING EROS AND NEUROSCIENCE 61 more needs to be said about the functional role of words like “love” in the script of progressing neuroscience, and further the important implications this yields for our current mode of practical reasoning. -

Some Unnoticed Implications of Churchland's Pragmatic Pluralism

Contemporary Pragmatism Editions Rodopi Vol. 8, No. 1 (June 2011), 173–189 © 2011 Beyond Eliminative Materialism: Some Unnoticed Implications of Churchland’s Pragmatic Pluralism Teed Rockwell Paul Churchland’s epistemology contains a tension between two positions, which I will call pragmatic pluralism and eliminative materialism. Pragmatic pluralism became predominant as his episte- mology became more neurocomputationally inspired, which saved him from the skepticism implicit in certain passages of the theory of reduction he outlined in Scientific Realism and the Plasticity of Mind. However, once he replaces eliminativism with a neurologically inspired pragmatic pluralism, Churchland (1) cannot claim that folk psychology might be a false theory, in any significant sense; (2) cannot claim that the concepts of Folk psychology might be empty of extension and lack reference; (3) cannot sustain Churchland’s critic- ism of Dennett’s “intentional stance”; (4) cannot claim to be a form of scientific realism, in the sense of believing that what science describes is somehow realer that what other conceptual systems describe. One of the worst aspects of specialization in Philosophy and the Sciences is that it often inhibits people from asking the questions that could dissolve long standing controversies. This paper will deal with one of these controversies: Churchland’s proposal that folk psychology is a theory that might be false. Even though one of Churchland’s greatest contributions to philosophy of mind was demonstrating that the issues in philosophy of mind were a subspecies of scientific reduction, still philosophers of psychology have usually defended or critiqued folk psychology without attempting to carefully analyze Churchland’s theory of reduction. -

Tools of Pragmatism

Coping with the World: Tools of Pragmatism Mind, Brain and the Intentional Vocabulary Anders Kristian Krabberød Hovedoppgave Filosofisk Institutt UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Høsten 2004 Contents 1. Introduction.................................................................................................. 2 2. Different Ways of Describing the Same Thing ........................................... 7 3. Rorty and Vocabularies ............................................................................. 11 The Vocabulary-Vocabulary ...............................................................................................13 Reduction and Ontology......................................................................................................17 4. The Intentional Vocabulary and Folk Psychology: the Churchlands and Eliminative Materialism ................................................................................ 21 Eliminative Materialism......................................................................................................22 Dire Consequences..............................................................................................................24 Objecting against Eliminative Materialism..........................................................................25 1. The first objection: Eliminative materialism is a non-starter........................................27 2. The second objection: What could possibly falsify Folk Psychology?...........................29 3. The third objection: Folk Psychology is used -

Paul Churchland

fair body of moderately successful theory described the way this fluid Paul Churchland substance--called "caloric"-- flowed within a body, or from one body to another, and how it produced thermal expansion, melting, boiling, and Eliminative Materialism (1984)* so forth. But by the end of the last century it had become abundantly clear that heat was not a substance at all, but just the energy of motion of Eliminative materialism (or eliminativism) is the radical claim that our ordinary, the trillions of jostling molecules that make up the heated body itself. Te common-sense understanding of the mind is deeply wrong and that some or all of new theory--the "corpuscular/kinetic theory of matter and hear'--was the mental states posited by common-sense do not actually exist. Descartes fa- much more successful than the old in explaining and predicting the mously challenged much of what we take for granted, but he insisted that, for the thermal behavior of bodies. And since we were unable to identify caloric most part, we can be confident about the content of our own minds. Eliminative fluid with kinetic energy (according to the old theory, caloric is a material materialists go further than Descartes on this point, since they challenge of the exis- substance; according to the new theory, kinetic energy is a form of mo- tence of various mental states that Descartes took for granted. tion), it was finally agreed that there is no such thing as caloric. Caloric —William Ramsey1 was simply eliminated from our accepted ontology. As the eliminative materialists see it…our common-sense psycholo- A second example. -

THE HORNSWOGGLE PROBLEM1 Patricia Smith Churchland, Department of Philosophy, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA

Journal of Consciousness Studies, 3, No. 5ñ6, 1996, pp. 402ñ8 THE HORNSWOGGLE PROBLEM1 Patricia Smith Churchland, Department of Philosophy, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA. Abstract: Beginning with Thomas Nagel, various philosophers have propsed setting con- scious experience apart from all other problems of the mind as ëthe most difficult problemí. When critically examined, the basis for this proposal reveals itself to be unconvincing and counter-productive. Use of our current ignorance as a premise to determine what we can never discover is one common logical flaw. Use of ëI-cannot-imagineí arguments is a related flaw. When not much is known about a domain of phenomena, our inability to imagine a mechanism is a rather uninteresting psychological fact about us, not an interesting metaphysical fact about the world. Rather than worrying too much about the meta-problem of whether or not consciousness is uniquely hard, I propose we get on with the task of seeing how far we get when we address neurobiologically the problems of mental phenomena. I: Introduction Conceptualizing a problem so we can ask the right questions and design revealing experiments is crucial to discovering a satisfactory solution to the problem. Asking where animal spirits are concocted, for example, turns out not to be the right question to ask about the heart. When Harvey asked instead, ëHow much blood does the heart pump in an hour?í, he conceptualized the problem of heart function very differently. The recon- ceptualization was pivotal in coming to understand that the heart is really a pump for circulating blood; there are no animal spirits to concoct. -

Scientific Realism and the Plasticity of Mind by Paul Churchland

BOOK REVIEWS obscurity of purpose makes his continual referencesto science seem irrelevantto our views about the nature of minds. This can only rein- force what Wilson would call the OA prejudices that he deplores. JANET LEVIN Universityof SouthernCalifornia ThePhilosophical Review, XCI, No. 2 (April 1982) SCIENTIFIC REALISM AND THE PLASTICITY OF MIND. By PAUL CHURCHLAND. New York and London, Cambridge University Press, 1979. Pp. x, 157. $19.95. Paul Churchland's book is an attempt to show how one can have a literal, realistic attitude to current scientific theory and at the same time see our current system of concepts as inconclusive, temporary, far fromany cadence. He wants to let us have both a Putnam-like scien- tific realism and a Feyerabend-like acknowledgment of the plasticity of our understanding. His main target is our understanding of mind, both because it is natural to expect that their scientifictheorizing will have some radical impact on our ordinary thinking,and because of the connections between one's theory of mind and one's theory of know- ledge. And, though Churchland is not explicit on this point, some of the most puzzling questions about realism and referencearise about the vocabulary of mind. Churchland begins by describing the continuity of commonsense and scientificbelief, arguing, much in the manner of Hanson, Good- man, or a number of others, that perceptual experience is something that is informed as much by one's beliefs as by what strikesone's re- ceptors. What is interestinghere is not so much these conclusions as his attempt to describe the malleability of perception by prior belief in such a way that it allows perception to bear a referentialrelation to the physical realities that prompt it. -

Introductory Lectures: the Nature and History of Cognitive Science Chapter 4: Philosophy’S Convergence Towards Cognitive Science by Dr

Introductory Lectures: The Nature and History of Cognitive Science Chapter 4: Philosophy’s Convergence Towards Cognitive Science By Dr. Charles Wallis Last revision: 9/24/2018 Chapter Outline 4.1 Introduction 4.2 The Scientific Explosion of the Early 20th Century 4.3 The Logical and Mathematical Explosion of the Early 20th Century 4.4 The Rise Logical Empiricism 4.5 Logical Behaviorism 4.6 Three Problems for Logical Behaviorism 4.7 Identity Theories: Reduction Through Reference Equivalence Rather Than Meaning Equivalence 4.8 Identity Theories: Type-Type Identity 4.9 Two Arguments For Type-Type Identity Theory 4.10 Identity Theories: Token-Token Identity 4.11 Functionalism 4.12 Computationalism 4.13 Property Dualism 4.14 Eliminative Materialism 4.15 Glossary of Key Terms 4.16 Bibliography The 20th Century and the Semantic Twist 4.1 Introduction Recall that ontological frameworks provide a general framework within which theorists specify domains of inquiry and construct theories to predict, manipulate, and explain phenomena within the domain. Once researchers articulate an ontological framework with sufficient clarity they begin to formulate and test theories. Chapter two ends with the suggestion that oppositional substance dualists face two major challenges in their attempt to transition from the articulation of an ontological framework to the formulation and testing of theories purporting to predict, manipulate, and explain mental phenomena. On the one hand, oppositional substance dualists have problems formulating theories providing explanations, predictions, and manipulations of the continual, seamless interaction between the mental and the physical. Philosophers often call this the interaction problem. On the other hand, the very nature of a mental substance--substance defined so as to share no properties with physical substance--gives rise to additional challenges. -

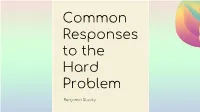

Common Responses to the Hard Problem

Common Responses to the Hard Problem Benjamin Stucky Semir Zeki Editorial in Book Consciousness: Theories in Neuroscience Multiple and Philosophy of Mind Consciousnesses? Original Paper Zeki (2003) The disunity of consciousness Chapter 5 Separation of mind from brain? Book: Transcendent Mind Non-aware arithmetic? Paper: Sklar et al. (2012) Reading and They use a different doing arithmetic nonconsciously definition of consciousness compared to our course! Privacy of Language? BBC Radio 4: Wittgenstein‘s Beetle in a Box Analogy youtube.com/watch?v=x86hLtOkou8 materialism somtimes physicalism matter dualism substance or property matter consciousness idealismidealism consciousness neutralneutralidealism monismmonism one substance neither matter nor mind Common responses to the hard question as categorized by Chalmers (2003) Consciousness and its Place in Nature A materialism there is no epistemic (knowledge) gap consciousness does not exists is fully definable by or eliminativism functions functionalism, behaviors behaviorism information computationalism A materialism water earth air fire Folk Psychology Argument: “ […] the correct account of cognition […] will bear about as much resemblance to Folk Psychology as modern chemistry bears to fourspirit alchemy. “ - Paul Churchland Alchemical symbols from: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alchemical_symbol A materialism Illusion/Belief Argument: “[…] something that is true: I am not introspectively aware that mental images are brain-processes to something that is false: I am introspectively aware that mental images are not brain-processes.” - DM Armstrong Cartoon by ciosuconstantin: toonpool.com/cartoons/Illusion_8114 A materialism Chinese room John Searle I do not understand Chinese. I am in a closed room an receive questions in Chinese. I answer them by using a rulebook which allows for perfect Chinese-English translation. -

Philosophy of Mind CRITICAL CONCEPTS in PHILOSOPHY

4-Volume Set Philosophy of Mind CRITICAL CONCEPTS IN PHILOSOPHY Edited and with a new introduction by Sean Crawford, University of Manchester, UK Philosophy of mind is concerned with fundamental issues about the relation between mind and body and mind and world, and with the nature of the diverse variety of mental phenomena, such as thought, self-knowledge, consciousness, perception, sensation, and emotion. Philosophers of mind explore some of the most perplexing questions about our mental lives. For instance: • How exactly is the mental related to the physical? • How is it that our thoughts can reach out to reality and refer to objects distant in time and space? • What is consciousness? Can it be explained by science? For as long as humanity has sought an understanding of its place in the universe, philosophy of mind has been at the centre of philosophy, but it flourishes now as it has never done before. This new title in the Routledge’s Major Works series, Critical Concepts in Philosophy, meets the need for an authoritative reference work to make sense of the subject’s enormous literature and the continuing explosion in research output. Edited by Sean Crawford, a prominent scholar in the field, it is a four-volume collection of classic and contemporary contributions to all of the major debates in philosophy of mind. With comprehensive introductions to each volume, newly written by the editor, which place the collected material in its historical and intellectual context, Philosophy of Mind— is an essential work of reference and is destined to be valued by philosophers of mind-as well as those working in allied areas such as metaphysics, epistemology, and philosophy of language; and cognate disciplines such as psychology—as a vital research tool.